Pruritus

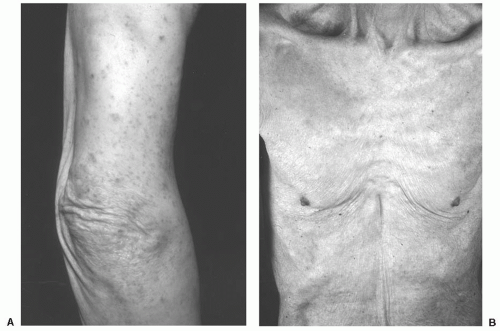

Pruritus, or itch, is a common, nonspecific complaint in the elderly that is often secondary to abnormally dry skin (

Fig. 24.1B). However, chronic, intractable pruritus accompanied by severe excoriations may be an indicator of internal malignancy (

1). This type of pruritus is most frequently encountered in patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma but may be observed with any internal malignancy (

2). There are often no true primary lesions on examination, but secondary changes including excoriations and subsequent lichenification and pigmentary alterations can be significant (

Fig. 24.1A). Pruritus has been reported in up to 25% of patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma and is classically described as intense and burning. It may be an indicator of less favorable prognosis when associated with fever or weight loss (

1,

2).

Pruritus may also be a sign of cholestatic liver disease, renal disease, human immunodeficiency virus disease, thyrotoxicosis, or diabetes (

1). Infestation with scabies should also be considered in the differential diagnosis. In contrast to the localized nature of nonmalignant pruritus, malignancyassociated pruritus tends to be generalized.

Intractable pruritus is best evaluated by a dermatologist, who can distinguish primary pruritus from pruritus secondary to another cutaneous condition. Workup should include a thorough history and physical examination with baseline evaluation of complete blood count (CBC), liver function tests (LFTs), and a chest x-ray. Skin biopsy of primary lesions, if present, may determine the cause of the pruritus. In addition, age-appropriate and symptom-directed cancer screening should be performed. Symptomatic treatment options include oral antihistamines (especially, sedating antihistamines), topical corticosteroids, and ultraviolet light therapy (

Table 24.2). Zylicz et al. (

3) have reported successful treatment of pruritus associated with cholestasis in disseminated cancer using buprenorphine with low-dose naloxone. The antipruritic effects of paroxetine (

4) and mirtazapine (

5) have also been documented. More recently, Goncalves et al. (

6) have reported that thalidomide alleviated refractory pruritus associated with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. However, malignancy-associated pruritus only definitively resolves with successful treatment of the underlying cancer (

7,

8).

Sign of Leser-Trélat

The sign of Leser-Trélat is the sudden increase in the number or size of seborrheic keratoses (SKs) in association with internal malignancy. It has been most commonly associated with gastric carcinomas (

9) but has been documented in lymphoid malignancies as well (

10). Although the sign has been attributed separately to Edmund Leser and Ulysse Trélat (

11,

12), it is now believed that both individuals were actually observing cherry hemangiomas. In fact, it was Hollander who first recognized the association between internal cancer and SKs in 1900 (

13). While the pathogenesis of Leser-Trélat remains unclear, evidence suggests that increases in tumorderived growth factors may play a role (

14).

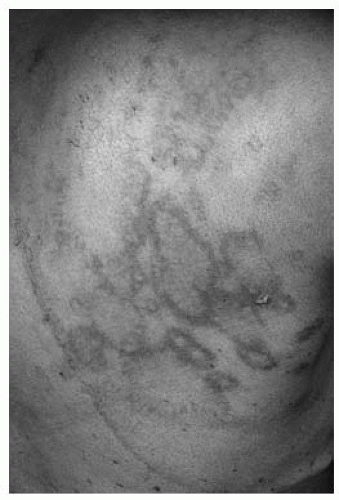

On physical examination, SKs are waxy, hyperpigmented papules or plaques (

Fig. 24.2) that appear to be “stuck on” and look as though they might be easily peeled away from the surface of the skin. Even though the lesions in Leser-Trélat frequently affect the back, chest, and extremities, the face and groin may also be involved (

12). SKs are extremely common in older individuals and represent no danger to patients. However, pruritus may be a prominent feature in some cases. The differential diagnosis includes benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions, including lentigines, nevi, actinic keratoses, atypical nevi, pigmented Bowen’s disease, and melanoma. Diagnosis can be confirmed by simple skin biopsy performed by a dermatologist.

It must be emphasized that although SKs are common, the sudden eruption of numerous lesions or their

appearance before the third decade is unusual and should prompt further investigation. A workup consists of a complete history and physical examination, routine blood studies (CBC and LFTs), chest x-ray, mammogram and Pap smear for women, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) for men. Endoscopic evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract should also be considered, along with any symptom-directed diagnostic studies. In one instance, Vielhauer et al. (

9) reported the diagnosis of occult renal cell carcinoma in a patient with Leser-Trélat. Curative nephrectomy was performed as a result of early diagnosis.

Of note, the presence of SKs itself is not dangerous to the patient and reassurance of this is necessary. However, if desired, skin lesions that are particularly irritating or cosmetically bothersome may be removed by curettage under local anesthesia with little risk of scarring. Other treatment methods include cryosurgery with liquid nitrogen and chemical cauterization with topical application of 70% trichloroacetic acid.

Erythema Gyratum Repens

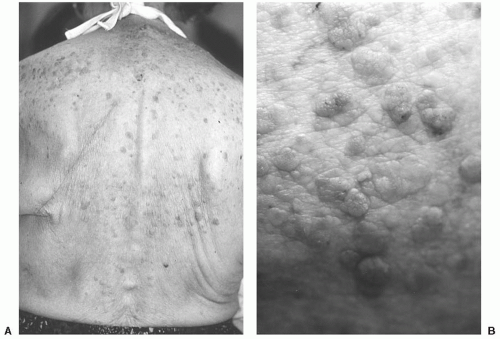

Erythema gyratum repens is part of the group of gyrate erythemas (

15) that share similar morphologic characteristics. These are reactive, inflammatory dermatoses that appear “figurate,” “polycyclic,” and “serpiginous” (

16). Gammel (

17) first described erythema gyratum repens in 1952, in association with breast carcinoma. Since that time, the overwhelming instances of cases have been associated with internal malignancies (

18).

The rash of erythema gyratum repens is quite distinct from that of other gyrate erythemas. On clinical examination, multiple serpiginous, erythematous bands take on a “wood grain” appearance (

Fig. 24.3) and are seen covering the trunk and proximal extremities (

19). There is usually scaling associated with the lesions and patients may complain of pruritus. Lesions may be indurated and are likely to migrate over the course of hours. Unlike the characteristic clinical picture, histopathologic findings are nonspecific and may include hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis, and

a superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (

15). Because deposits of immunoglobulin (Ig)G and C3 have been found at the basement membrane of lesional skin, erythema gyratum repens is thought to be mediated by an immune response to the presence of tumor antigens (

20).

On suspicion of erythema gyratum repens, dermatologic consultation is required for confirmation. Because of the likelihood of association with internal malignancy, an extensive search for malignancy is indicated. Standard screening laboratory and imaging studies should be performed with special attention toward ruling out cancer of the lung (

18,

19), with which the rash is most commonly associated (

21). Erythema gyratum has also been reported with esophageal (

10) breast and renal cancer (

22). In rare cases, it has even been found in the absence of malignancy (

23). However, the cutaneous eruption may precede the onset of malignancy, so it is important to repeat screening tests periodically.

The most effective treatment of cutaneous lesions is therapy targeting the underlying tumor (

19). Skin manifestations may resolve after removal of localized tumors but can persist until death in widespread disease. Associated pruritus and inflammation can be treated with oral antihistamines and mid-potency topical corticosteroids (

Table 24.2).

Hypertrichosis Lanuginosa Acquisita

Hypertrichosis lanuginosa acquisita (HLA), also referred to as malignant down, is characterized by the growth of fine, non-pigmented hair that occurs primarily on the face (

10). It is most commonly associated with small cell and non-small cell carcinoma of the lung (

24) and colorectal cancer (

25) but has also been reported with carcinomas of the kidney (

26), pancreas (

27), breast (

28), and metastatic melanoma (

29). Furthermore, HLA has been associated with other conditions including shock, thyrotoxicosis, and porphyria and ingestion of drugs including cyclosporine, streptomycin, phenytoin, spironolactone, diazoxide, minoxidil, interferons, and corticosteroids (

10,

16).

In malignancies, HLA frequently appears after the tumor has already metastasized and its presence usually implies poor prognosis with a survival time of less than 2 years (

10). However, lanugo hair growth can appear before the tumor is diagnosed (

28). Thus, for patients presenting with HLA, blood examination, chest x-ray, and colonoscopy are advised (

30).

The most effective treatment for HLA is successful removal of the underlying tumor. Cosmetic management may be attempted through electrolysis, depilatories, or shaving. Because the hairs are not pigmented, treatment with hair removal laser would likely be unsuccessful because lasers target melanin in the hair follicle. Treatment with eflornithine HCl cream (13.9%) applied to the affected area twice daily may be effective. This agent inhibits ornithine decarboxylase, a key hair cycle enzyme, and may result in noticeably diminished hair growth (

31).

Necrolytic Migratory Erythema

Necrolytic migratory erythema (NME) is present in almost 70% of patients with glucagonoma (

32), a condition caused by a rare neuroendocrine tumor of pancreatic islet α-cells (

33). The eruption begins as an erythematous patch involving the groin and spreads to the buttocks, perineum, thighs, and lower extremities (

Fig. 24.4).

The erythematous areas eventually undergo scaling and blister formation. Erosions with superficial crusting occur subsequent to the rupture of blisters and healing with induration and pigmentary change follows over the course of several weeks. This may follow a relapsing and remitting course and may be associated with stomatitis. The differential diagnosis includes intertrigo, superficial candidiasis,

bullous drug eruption, and pemphigus (

21,

33). Histologic findings include dyskeratotic epidermal cells with superficial epidermal necrosis (

Fig. 24.4D) (

33). The diagnostic features include elevated plasma glucagon levels. Dermatologic consultation should be sought to confirm the diagnosis as well as to rule out other skin disorders that may mimic NME.

As with other paraneoplastic syndromes, effective tumor ther apy results in the improvement of cutaneous symptoms (

32). Unfortunately, patients with NME may have metastatic disease at presentation. There have been reports of successful treatment of cutaneous symptoms using the somatostatin analog octreotide. Poggi et al. (

34) reported complete resolution of skin lesions with octreotide after surgery and radiotherapy in a patient with hepatic metastases. Resolution may be noted as early as one week after beginning therapy, but resistance can develop. While waiting for response, denuded areas should be gently cleansed twice daily, covered with a bland emollient, and dressed with a nonstick bandage. Appropriate monitoring for secondary infection is indicated and is especially important in the hospitalized patient.

NME has also been reported in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome without glucagonoma or evidence of pancreatic disease (

35). Recently, NME was diagnosed in a patient with glucagon cell adenomatosis (

36).