Treatment Effects

The combination of breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy is now the local treatment method of choice for most patients with invasive breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).1,2 Some patients treated in this manner require subsequent biopsy of the irradiated breast because of the development of a new abnormality on physical examination or mammography. Therefore, the surgical pathologist must be familiar with the effects of radiation on the breast.

In addition, neoadjuvant (preoperative) chemotherapy is being used increasingly to treat patients with invasive breast cancer.3, 4, 5 and 6 In this treatment approach, a core-needle biopsy of the breast tumor is performed to obtain tissue for diagnosis and to assess hormone receptor and HER2 status. Systemic therapy (i.e., chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, HER2-targeted therapy) is then administered before definitive surgery (i.e., excision or mastectomy). Although the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy does not improve survival when compared with adjuvant (postoperative) chemotherapy, it reduces the tumor size sufficiently to permit breastconserving surgery in some patients who would otherwise require a mastectomy.7, 8 and 9 In addition, neoadjuvant treatment provides the opportunity to obtain early information about tumor responsiveness to a given systemic therapy regimen.6 Thus, the potential to tailor drug combinations earlier in the course of treatment is an added benefit of this approach. Given the increasing use of neoadjuvant treatments, pathologists must become familiar with chemotherapy-related alterations in both breast cancers and non-neoplastic breast tissue. Furthermore, it is necessary to have an understanding of how to evaluate breast specimens obtained after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in order to properly assess the response to chemotherapy.

RADIATION EFFECTS

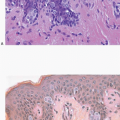

Radiation-induced changes in the skin of the breast are identical to those described in irradiated skin from other sites and include epidermal atrophy and telangiectasia.10 The nature of these changes is, in part, dependent upon the interval between irradiation and histological examination.

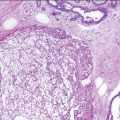

Patients with invasive cancer and DCIS treated by breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy occasionally develop areas of fat necrosis in the vicinity of the primary tumor site. These lesions may clinically, mammographically, and macroscopically resemble carcinoma.11 Although the diagnosis of fat necrosis can be readily made on core-needle biopsy, whether the changes in the needle biopsy samples are fully representative of the lesion in the breast may be a matter of concern. In such cases, careful pathologic-radiologic-clinical correlation is essential in order to avoid the underdiagnosis of breast cancer recurrence. If there is doubt about whether or not the core-needle biopsy samples are representative, a surgical excision should be performed.

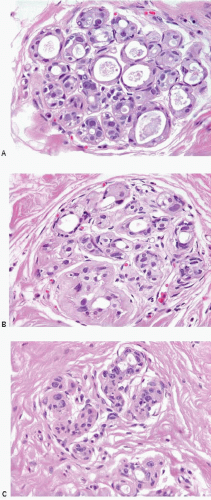

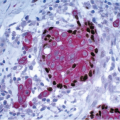

A characteristic constellation of histological changes is observed in non-neoplastic breast tissue in patients treated by breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy.12 The most frequent finding is that of scattered atypical epithelial cells in the terminal duct lobular unit (TDLU), usually associated with variable degrees of lobular sclerosis and atrophy. These atypical cells are large, with enlarged, diffusely hyperchromatic nuclei, generally small or inconspicuous nucleoli, and finely vacuolated eosinophilic cytoplasm. The cells often protrude into the lumen of the involved duct or acinus but do not show evidence of proliferation such as cellular stratification, loss of polarity, or mitotic activity (Fig. 19.1, e-Figs. 19.1, 19.2 and 19.3).

Radiation effects in the TDLU must be distinguished from carcinoma to prevent an incorrect diagnosis of tumor recurrence. The distinction between radiation change and lobular carcinoma in situ is not difficult because of the characteristic histologic appearance of the latter (i.e., a monotonous population of relatively small cells that fill and distend small ducts and acini). The differentiation of radiation-induced changes from DCIS involving the TDLU (cancerization of lobules) may be more difficult. However, when DCIS involves the TDLU, there is generally evidence of cellular proliferation as characterized by cellular stratification, loss of polarity, and distension of the involved ducts and acini. In addition, the nuclei in carcinoma cells tend to show irregularly dispersed chromatin and variably prominent nucleoli. Finally, necrosis of varying degrees may be seen with DCIS, and mitoses may be apparent. Conversely, the epithelial cells in areas of radiation change generally show maintenance of cellular polarity and cohesion, lack of stratification, a diffuse homogeneous increase in chromatin, usually small or inconspicuous nucleoli, and no evidence of necrosis or mitotic activity. In some instances of radiation change, there may be extensive lobular fibrosis and atrophy with distortion of the lobular architecture. Entrapment of acini containing atypical epithelial cells may result in a pseudoinfiltrative pattern, thereby simulating invasive carcinoma. However, the lobulocentric configuration of such areas is usually apparent on low-power examination.

TABLE 19.1 Key Features of Radiation Effects in Non-neoplastic Breast Tissue | |

|---|---|

|

Additional pathological changes that may be observed in non-neoplastic irradiated breast tissue include epithelial atypia in large (extralobular) ducts, atypical fibroblasts in the stroma, and vascular changes, such as myointimal hyperplasia in small arteries and prominent capillary endothelial cells.12 However, these changes tend to be most pronounced in cases in which the alterations in the TDLU are marked. It is important to note that stromal fibrosis, a well-recognized feature of radiation effect in other organs, is so variable in both irradiated and non-irradiated breasts that it cannot by itself be considered a constant and reliable histological indicator of prior irradiation in the breast.

The key features of radiation changes in non-neoplastic breast tissue are summarized in Table 19.1.

CHEMOTHERAPY EFFECTS

Histopathologic alterations attributable to chemotherapy may be seen in both non-neoplastic breast tissue and breast cancers.

Changes in Non-neoplastic Breast Tissue

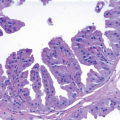

Non-neoplastic breast tissue shows atrophic changes and a considerable reduction in the volume of lobular tissue compared with tissue from untreated women of similar age. Lobular sclerosis is often present as well as attenuation of the epithelium lining the ducts and lobules; this results in the appearance of a prominent myoepithelial cell layer.13, 14 and 15 Nuclear atypia in the non-neoplastic epithelium similar to that described earlier after radiation treatment is seen in some patients treated with chemotherapy.13,14,16

Changes in Breast Cancers

The pathologist has a critical role in assessing the tumor response in breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy because clinical examination and imaging studies are associated with both high false-positive and high false-negative rates. Oriented excision specimens should be inked in multiple colors as described in Chapter 20. Specimen radiographs are helpful for locating the site of the tumor bed, which at most institutions is marked with a radiopaque clip at the time of the pretreatment diagnostic core-needle biopsy.16,17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree