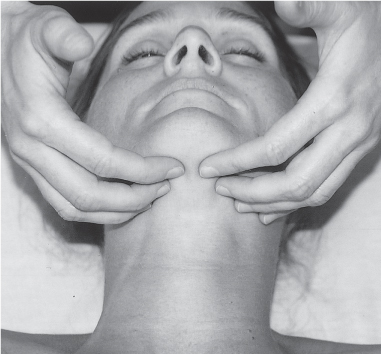

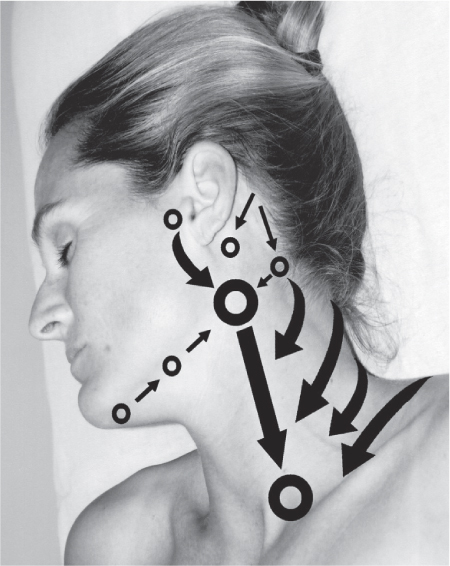

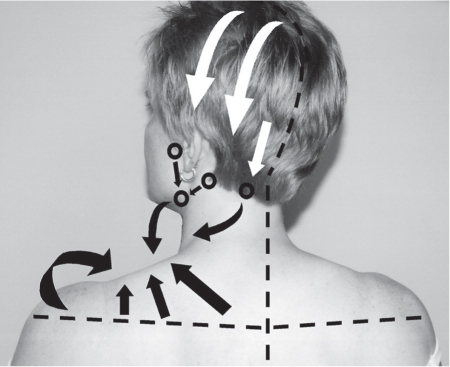

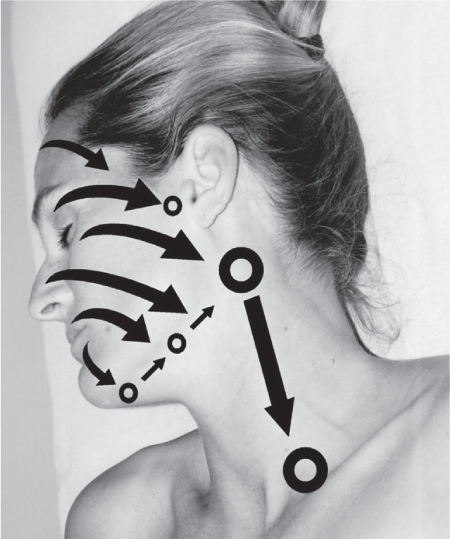

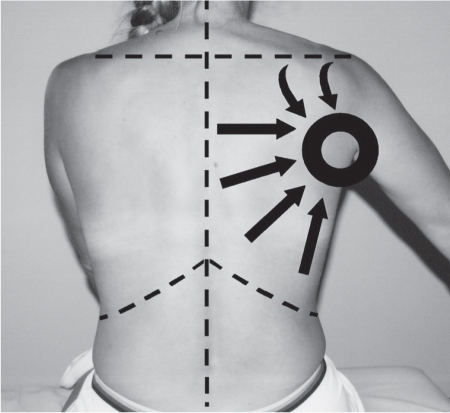

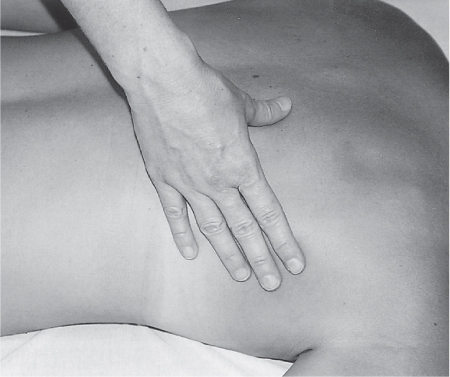

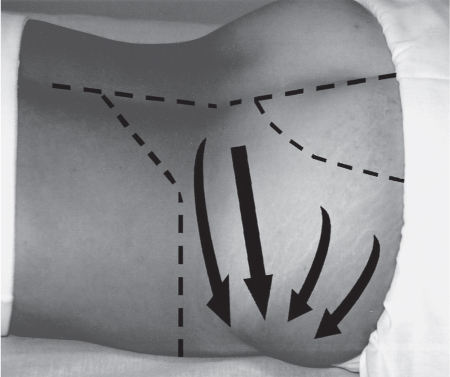

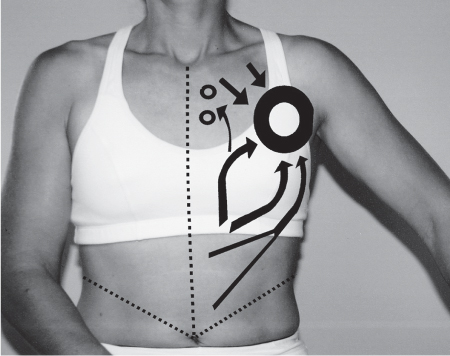

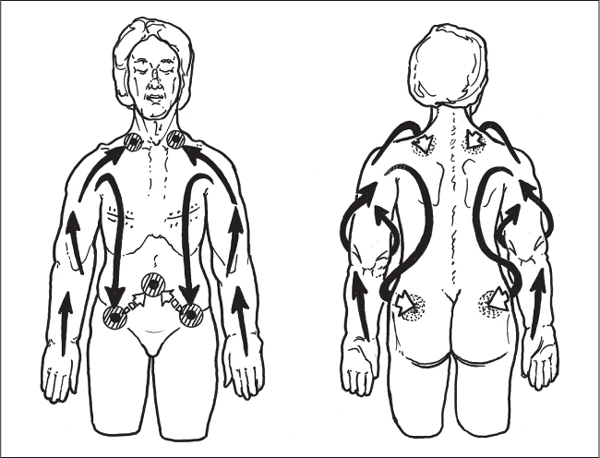

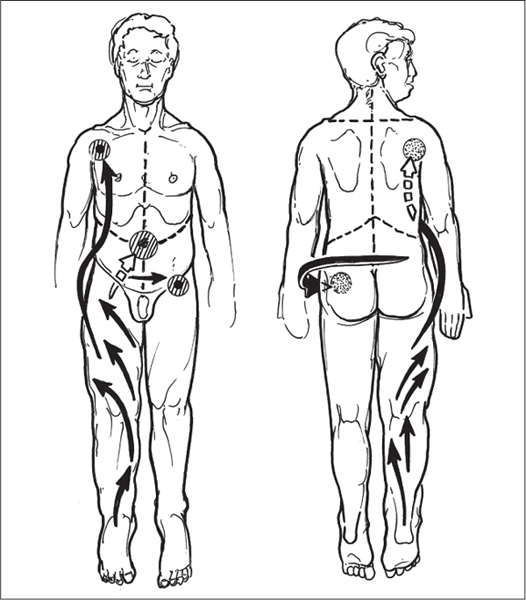

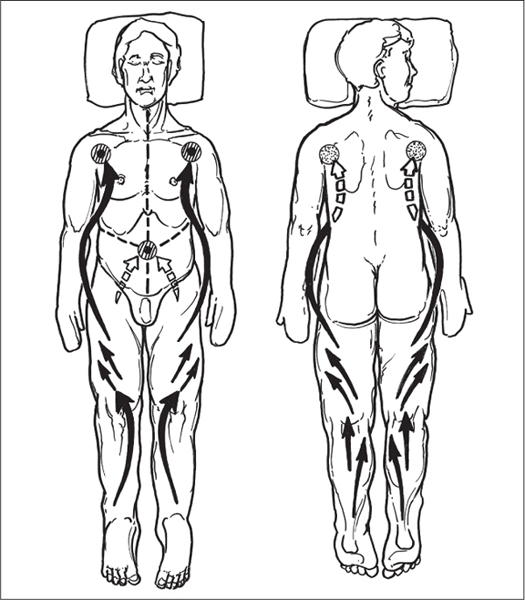

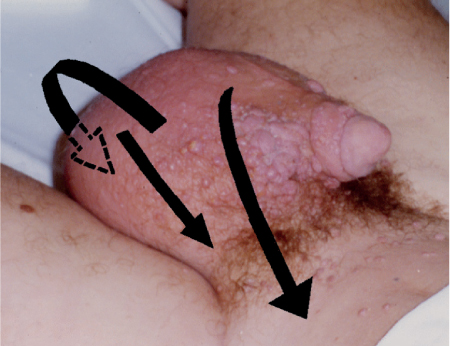

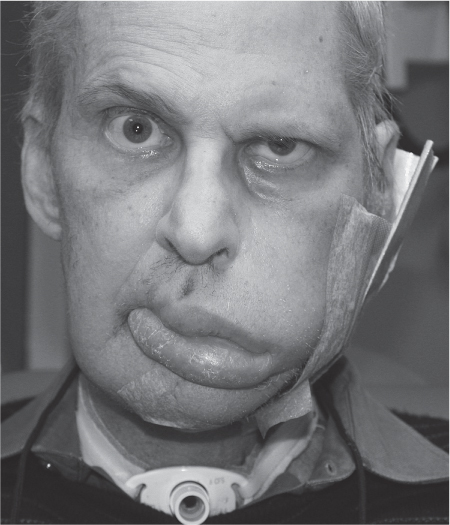

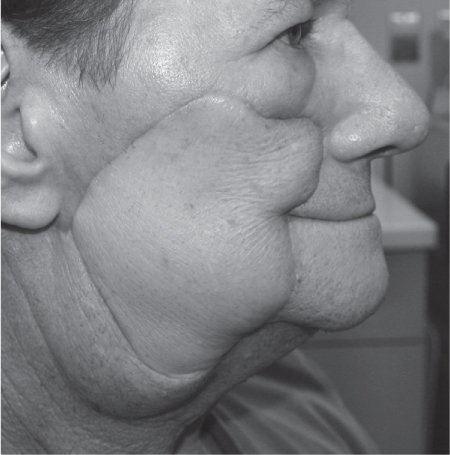

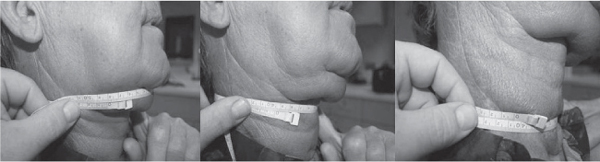

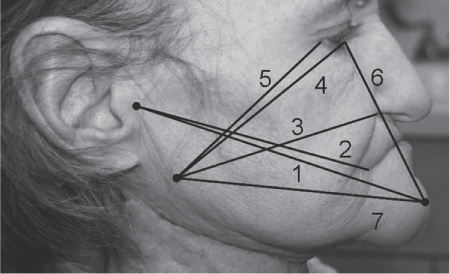

5 Treatment Application of Basic MLD Techniques on Different Parts of the Body Treatment Strategies for Common Complications of Lymphedema CDT Treatment Protocol Variations: Primary and Secondary Lymphedema Adapting CDT to the Palliative Patient Lipedema Treatment: Understanding the Diagnosis and Patient Profile Application of Compression Bandages Bandaging Procedures Using Foam Padding Bandaging in Presence of Wounds Measurements for Compression Garments Compression Bandaging Alternatives: Guidelines to Choosing the Right Home Care Systems Treatment Considerations in Managing the Morbidly Obese Patient The techniques outlined in this chapter should not be substituted for the thorough instructions provided in comprehensive lymphedema management courses offered by qualified training centers. As with many manual techniques, the skills required to deliver adequate intervention using all components of complete decongestive therapy cannot be learned from reading a book, watching videos, or attending weekend classes. A high level of competency and skill is needed to master all components of CDT and to provide patients with a proper degree of intervention. The quality of training will have a great impact on the level of care the patients receive or do not receive. CDT and its components have been practiced safely and effectively in Europe for many decades and became the standard of treatment for lymphedema in the 1970s, when the national health insurance system in Germany started to reimburse for lymphedema treatment. To ensure proper teaching standards, training centers in Germany have to comply with strict guidelines specified by professional organizations in the training and certification of lymphedema instructors as well as therapists. Certain organizations in the United States have acknowledged the need for certification programs in lymphedema management to ensure a base of knowledge considered fundamental in the treatment of lymphedema and related conditions. The four basic techniques of Dr. Vodder’s manual lymph drainage (MLD)—stationary circle, pump, scoop, and rotary—their effects on the lymphatic system, and the contraindications for manual lymph drainage are discussed in Chapter 4. Additional techniques incorporated into MLD sequences are soft and rhythmic strokes known as effleurage. This method is adopted from more traditional massage techniques and is used to stimulate local sympathetic activity and to promote directional flow of lymph. The techniques and sequences outlined in the following sections are applied in conditions where edema is present, but the lymph nodes are not removed or treated with irradiation. Examples include post-traumatic and postoperative swelling, lower extremity edema caused by pregnancy, swellings caused by partial or complete loss of mobility (pareses, paralysis), reflex sympathetic dystrophy (when swelling is present), migraine headache (swelling is present in the perivascular areas of intracranial blood vessels), cyclic idiopathic edema, and rheumatoid arthritis. Selected indications are cited in the appropriate sections. Basic treatment sequences may also be used to accomplish a general increase in lymph circulation or to achieve a common soothing effect by decreasing sympathetic activity. In the treatment of lymphedema, these techniques are used to improve lymph production and lymph angiomotoricity, as well as to promote the lymphatic return from the drainage areas described in Chapter 4 (Intensive Phase) to the venous system. In the lymphedematous extremity and/or body part, the treatment sequences are modified accordingly, as outlined later in this chapter. Common denominators to all techniques and sequences are the following: • The hand positions of all basic strokes are adapted to the anatomy and physiology of the lymphatic system. • Central pretreatment: the areas closest to the venous angles and regional groups of lymph nodes are stimulated first. This allows for drainage of the peripheral areas. At extremities, the stimulation begins proximal and is continued toward distal, in accordance with the direction of the lymph drainage. • Stroke intensity: the applied pressure in individual strokes should be enough to utilize full elasticity of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, and to promote lymph formation and lymph angiomotoricity. Too much pressure may cause unwanted vasodilation and lymphangiospasm. • Stroke sequence: each technique consists of a working and resting phase, during which the manual pressure increases and decreases gradually. The goal in the working phase is to promote lymph formation, lymph angiomotoricity, and directional flow by stretching the anchoring filaments and smooth musculature located in the wall of lymph angions. The suction effect created in the resting phase results in a refilling of lymph collectors with lymph fluid from more distal areas. • Stroke duration: the relatively high viscosity of lymph fluid requires the working phase to last ~1 second. To ensure adequate reaction of the lymph collectors to the manual stimuli, the strokes should be repeated 5 to 7 times in one area. • Working direction of the strokes: the direction of the strokes depends on the anatomical actualities and generally follows the physiological patterns of lymphatic drainage. If surgery, radiation, or trauma results in an interruption of regular drainage pathways, it will become necessary to redirect the lymph flow around the blocked areas and toward regions with sufficient lymph flow patterns. Selected indications: pretreatment for other drainage areas*; postsurgical (oral, dental, plastic surgery, etc.) and post-traumatic swellings (whiplash injury, others); migraine headache; partial treatment for primary head and neck lymphedema; general increase in lymph circulation, or to achieve a common soothing effect by decreasing sympathetic activity. * An abbreviated sequence is used if the lateral neck serves as a pretreatment for other drainage areas. This shorter sequence consists of the first three techniques used in the complete sequence (see following page). Patient in supine position, therapist on the patient’s side: 1. Effleurage, 2 or 3 times from the sternum to the acromion 2. Manipulation of the inferior cervical lymph nodes Stationary circles in the supraclavicular fossa (horizontal plane) 3. Manipulation of the deep lateral cervical lymph nodes (Fig. 5.1) Stationary circles from the earlobe to the supraclavicular fossa in two hand placements, if necessary (sagittal plane) 4. Manipulation of the parotid and retroauricular lymph nodes (Fig. 5.2) Stationary circles with fingers in front of and behind the ear, followed by reworking the deep lateral cervical lymph nodes as in step 3 (both placements in sagittal plane) Patient in supine position, therapist at the head-end of the patient: 5. Manipulation of submandibular lymph nodes (Fig. 5.3) Stationary circles with distal phalanges (2–5) from the tip of the chin in the direction of the angle of the jaw (superior cervical lymph nodes). Two hand placements if necessary (phalanges in horizontal plane). This technique is followed by reworking the deep lateral cervical lymph nodes as in step 3. Patient in supine position, therapist on the patient’s side: 6. Manipulation of the shoulder collectors Stationary circles in 2 hand placements, which should cover the area located cranial to the anterior and posterior upper horizontal watershed. First hand placement on the acromion, second hand placement on the medial shoulder (both placements in horizontal plane). 7. Effleurage (as in step 1) Review Fig. 5.4 for drainage areas on the lateral neck. 1. Effleurage, 2 or 3 times from the sternum to the acromion 2. Manipulation of the inferior cervical lymph nodes Stationary circles in the supraclavicular fossa (horizontal plane) 3. Manipulation of the deep lateral cervical lymph nodes (Fig. 5.1) Stationary circles from the earlobe to the supraclavicular fossa in 2 hand placements, if necessary (sagittal plane) Selected indications: postsurgical (oral, dental, plastic surgery, etc.) and post-traumatic swellings (whiplash injury, others); migraine headache; partial treatment for primary head and neck lymphedema; general increase in lymph circulation, or to achieve a common soothing effect by decreasing sympathetic activity (Fig. 5.5) Pretreatment: lateral neck Patient in prone position, therapist at the head-end of the patient: 1. Effleurage, 2 or 3 three times starting at the back of the head and following the descending trapezius muscle to the acromion 2. Manipulation of the deep lateral cervical lymph nodes Stationary circles starting at the angle of the jaw in the direction of the supraclavicular fossa (sagittal plane). Two hand placements if necessary. 3. Manipulation of the occipital and parietal region Alternating stationary circles in several tracks, starting on the posterior head toward the parietal area (frontal plane). Working phase in the direction of the occipital and retroauricular lymph nodes. 4. Manipulation of the parotid and retroauricular lymph nodes Stationary circles with fingers in front of and behind the ear, followed by reworking the deep lateral cervical lymph nodes as in step 2 (both placements in sagittal plane) 5. Manipulation of the shoulder collectors Alternating pump techniques on both shoulders, starting at the acromion, following the upper trapezius muscle in the direction of the supraclavicular fossa Both hands in horizontal plane 6. Manipulation of the inferior cervical lymph nodes Bimanual thumb circles in the supraclavicular fossa (horizontal plane) Patient in prone position, therapist on the patient’s side: 7. Manipulation of the paravertebral lymph nodes and vessels Stationary circles paravertebrally with the finger pads (working deep) 8. Effleurage (as in step 1) Selected indications: postsurgical (oral, dental, plastic surgery, etc.) and post-traumatic swellings (whiplash injury, etc.); migraine headache; partial treatment for primary head and neck lymphedema; general increase in lymph circulation, or to achieve a common soothing effect by decreasing sympathetic activity (Fig. 5.6) Pretreatment: lateral neck (posterior neck if necessary) Patient in supine position, therapist at the head-end of the patient: 1. Effleurage, 2 or 3 times along lower jaw, upper jaw, the cheek, and the forehead in the direction of the angle of the jaw (following the pathway of the collectors) 2. Manipulation of the submental and submandibular lymph nodes (Fig. 5.3) Stationary circles with distal phalanges (2–5) from the tip of the chin in the direction of the angle of the jaw (superior cervical lymph nodes). Two hand placements if necessary (phalanges in horizontal plane). This technique is followed by stationary circles along the deep lateral cervical lymph nodes (sagittal plane). 3. Manipulation of the lower and upper jaw Alternating stationary circles working toward the submandibular lymph nodes. This technique is followed by stationary circles in the direction of the angle of the jaw and the supraclavicular fossa as described in step 2. 4. Manipulation of the lymph vessels in the area of the bridge of the nose and cheek Alternating stationary circles starting at the bridge of the nose, to include the lower eyelid, toward the cheeks. This technique is followed by the technique described in step 2, with the purpose of manipulating the lymph fluid toward the supraclavicular fossa. 5. Manipulation of the upper eyelid and eyebrows Alternating stationary circles (one or more fingers) in the direction of the preauricular lymph nodes (option: eyebrow roll) 6. Manipulation of the forehead and temporal area Stationary circles starting at the middle of the forehead, traveling to the temple with the working phase directed toward the preauricular lymph nodes 7. Manipulation of the parotid and retroauricular lymph nodes Stationary circles with fingers in front of and behind the ear, followed by stationary circles along the deep lateral cervical lymph nodes (sagittal plane) 8. Effleurage (as in step 1) The treatment area is outlined by the lower horizontal watershed (caudal limitation), the upper horizontal watershed (cranial limitation), and the sagittal watershed (medial limitation) (Fig. 5.7). Selected indications: Pretreatment for unilateral secondary upper extremity lymphedema (this sequence is applied on the healthy quadrant); postsurgical and post-traumatic swellings; general increase in lymph circulation, or to achieve a common soothing effect by decreasing sympathetic activity Pretreatment: lateral neck (abbreviated; see lateral neck sequence, steps 1–3) Patient in prone position, therapist contralateral to the healthy quadrant: 1. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes Stationary circles bimanually with flat hands between the latissimus dorsi and pectoral muscles (sagittal plane), with the working direction toward the apex of the axilla (subclavian trunk) 2. Effleurage, 2 or 3 times in several pathways, starting at the posterior sagittal watershed in the direction of the axillary lymph nodes (following the pathway of the collectors) 3. Manipulation of the lateral thorax Stationary circles alternating and dynamic from the horizontal watershed toward the axillary lymph nodes (sagittal plane). This sequence follows the thoracic portion of the inguinal axillary (IA) anastomosis. 4. Manipulation of the posterior thorax (Fig. 5.8) Rotary techniques in several tracks starting at the sagittal watershed in the direction of the axillary lymph nodes (following the pathway of the collectors). This technique should cover the entire treatment area as outlined previously (Fig. 5.7). 5. Manipulation of the posterior and lateral thorax Combination of alternating rotary techniques (upper and lower hands) starting at the sagittal watershed (lower hand is parallel to and just above the lower horizontal watershed). The rotary techniques travel alternating toward the lateral direction until the thoracic portion of the IA anastomosis is reached. Dynamic stationary circles follow this technique as outlined in step 3. 6. Manipulation of the posterior axillo-axillary (PAA) anastomosis Bimanual stationary circles, with the working phase directed toward the axillary lymph nodes. The hands are aligned parallel with the sagittal watershed (frontal plane). 7. Manipulation of the paravertebral lymph nodes and vessels (if necessary) Stationary circles paravertebrally with the finger pads (working deep) 8. Manipulation of intercostal lymph vessels Stationary circles, with the finger pads working from lateral placements to medial placements, using wavelike movements, with pressure working deep (perforating precollectors) 9. Effleurage (as in step 1) The treatment area is outlined by the lower horizontal watershed (cranial limitation), the horizontal gluteal fold (caudal limitation), and the sagittal watershed (medial limitation) (Fig. 5.9). Selected indications: Pretreatment for unilateral secondary and primary lower extremity lymphedema (this sequence is applied on the healthy quadrant); phlebolymphostatic edema; lipedema and lipolymphedema; postsurgical and post-traumatic swellings; general increase in lymph circulation, or to achieve a common soothing effect by decreasing sympathetic activity Pretreatment: lateral neck (abbreviated; see lateral neck sequence, steps 1–3), abdomen, inguinal lymph nodes Patient in prone position, therapist contralateral to the healthy quadrant: 1. Effleurage, 2 or 3 times in several pathways, starting at the posterior sagittal watershed toward the inguinal lymph nodes (remaining in the lumbar quadrant) 2. Manipulation of the lumbar area Alternating rotary techniques from the sagittal watershed toward the hip (ASIS). The upper hand is parallel to and just below the lower horizontal watershed; the lower hand follows the collectors of the posterior interinguinal (PII) anastomosis. 3. Manipulation of the PII anastomosis Bimanual stationary circles simultaneously on the PII anastomosis, with working direction toward the inguinal lymph nodes. Both hands are parallel to the sagittal watershed (frontal plane). 4. Manipulation of the paravertebral lymph nodes and vessels (if necessary) Stationary circles paravertebrally with the finger pads (working deep) 5. Effleurage (as in step 1) The treatment area is outlined by the lower horizontal watershed (caudal limitation), the upper horizontal watershed (cranial limitation), and the sagittal watershed (medial limitation) (Fig. 5.10). Selected indications: Pretreatment for unilateral secondary and primary upper extremity lymphedema (this sequence is applied on the healthy quadrant); postsurgical and post-traumatic swellings; general increase in lymph circulation, or to achieve a common soothing effect by decreasing sympathetic activity Pretreatment: lateral neck (abbreviated; see lateral neck sequence, steps 1–3) Patient in supine position, therapist contralateral to the healthy quadrant: 1. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes Bimanual stationary circles, with flat hands between the latissimus dorsi and pectoral muscles (sagittal plane), with the working direction toward the apex of the axilla (subclavian trunk) 2. Effleurage, 2 or 3 times in several pathways (following the collectors), starting at the anterior sagittal watershed in the direction of the axillary lymph nodes (not over the nipple) 3. Manipulation of the lymph vessels in the healthy mammary gland This technique is performed with a combination of alternating and dynamic pump and rotary techniques. The lower hand starts with dynamic pump techniques in three placements in the direction of the axillary lymph nodes: the first placement is on the mammary fold, the second placement in the glandular tissue, and the third placement below the nipple. The upper hand uses rotary techniques starting at the anterior sagittal watershed, following a line below the upper horizontal watershed in 3 hand placements toward the axillary lymph nodes. 4. Manipulation of the lateral thorax Dynamic and alternating stationary circles from the lower horizontal watershed toward the axillary lymph nodes (sagittal plane). This sequence follows the thoracic portion of the IA anastomosis. 5. Manipulation of the anterior and lateral thorax Combination of alternating rotary techniques (upper and lower hands) starting at the anterior sagittal watershed (lower hand is parallel to and just above the lower horizontal watershed). The rotary techniques travel alternating in the lateral direction until the thoracic portion of the IA anastomosis is reached. The technique is then followed by dynamic stationary circles, which follow the IA anastomosis toward the axillary lymph nodes (as outlined in step 4). 6. Manipulation of the anterior axillo-axillary (AAA) anastomosis Bimanual stationary circles, with the working phase directed toward the axillary lymph nodes. The hands are aligned parallel with the anterior sagittal watershed (frontal plane). 7. Manipulation of the parasternal lymph nodes and vessels (if necessary) Stationary circles parasternally with finger pads (working deep) 8. Manipulation of intercostal lymph vessels (Fig. 5.11) Stationary circles with 3 or 4 finger pads working from lateral placements to medial placements, using wavelike movements with pressure working deep (perforating precollectors) 9. Effleurage (as in step 2) Refer to the list of local contraindications for the abdominal area in Chapter 4, Contraindications for Manual Lymph Drainage. Abdominal techniques should not be applied if they cause pain or discomfort, or directly following meals. Patients should empty their bladder before treatment starts. Abdominal sequences can be separated into superficial and deep techniques. The skillful manipulation of the intra-abdominal areas, especially when combined with diaphragmatic breathing, results in increased lymph transport within the thoracic duct and larger lymphatic trunks. A decongestive effect on organ structures located within the abdominal and pelvic cavities, as well as on lymphatic drainage areas located more distally (the lower extremities), is additionally realized when performing abdominal techniques. Selected indications: part of the treatment sequence for lower extremity lymphedema (primary and secondary) as well as lymphedema involving the external genitalia; chronic venous insufficiency stages II and III (phlebo-lymphostatic edema); lipedema and lipolymphedema; part of the treatment sequence for primary lymphedema of the genitalia; part of the treatment sequence for upper extremity lymphedema (particularly with removal or irradiation of both axillary lymph node groups); part of the treatment for cyclic idiopathic edema; general increase in lymph circulation Pretreatment: lateral neck (abbreviated; see lateral neck sequence, steps 1–3) Patient in supine position, with the legs and the head elevated and the arms resting on the patient’s side; therapist on patient’s right side (next to pelvis): 1. Effleurage Two or three times starting at the pubic bone, following the rectus abdominis muscle to the xiphoid process, then along the thoracic cage and the iliac crest back to the pubic bone Two or three times following the ascending, transverse, and descending part of the colon 2. Manipulation of the colon Descending colon: The right hand is placed on the descending colon, with the fingertips on the thoracic cage and the fingers pointing up toward the midclavicular point. This is a two-handed technique; the bottom hand (right hand) is in contact with the skin and remains passive; pressure is applied with the left hand, which rests on top of the right hand. Working phase: Moderate (but soft) pressure is applied down into the abdomen (deep), then along and in the direction of the descending colon (caudal), ending in a partial supination directed toward the cisterna chyli. The hand relaxes in the resting phase, and the tissue elasticity carries the hand back to the starting position. This sequence is repeated 2 or 3 times. Ascending colon: The therapist is on the patient’s right side (next to the thorax, facing the direction of the patient’s feet). The right hand is placed on the ascending colon, with the fingertips near the inguinal ligament and the fingers pointing downward toward the pubic bone. The right hand, which is in contact with the skin, remains passive; pressure is applied with the left hand, which rests on top of the right hand. Working phase: Moderate (but soft) pressure is applied down into the abdomen (deep), then along and in the direction of the ascending colon (cranial), ending in a partial supination directed toward the cisterna chyli. The hand relaxes in the resting phase, and the tissue elasticity carries the hand back to the beginning position. This sequence is repeated 2 or 3 times. 3. Effleurage (as in step 1) With this technique, the caudal part of the thoracic duct, the cisterna chyli, the larger lymphatic trunks, the pelvic and lumbar lymph nodes, and the organ structures with their lymphatic system are stimulated. Deep abdominal sequences are applied on 5 different hand placements on the abdominal area and are combined with the patient’s diaphragmatic breathing (Fig. 5.12). To avoid hyperventilation, the therapist performs only one sequence per placement. Ideally, the placements on the thoracic cage and in the center of the abdomen are repeated during the full sequence, resulting in a total of 9 manipulations (depending on the patient’s reaction). During each manipulation, the therapist’s hand follows the patient’s exhalation into the abdominal area and offers moderate (but soft) resistance to the initial subsequent inhalation phase. The therapist then releases the resistance and stays in skin contact until the end of the inhalation phase. The hand is moved to the next placement on the abdomen during the pause between inhalation and the next exhalation phase. To avoid discomfort, the hand, which is in contact with the patient’s skin, remains soft and passive. Pressure is applied with the top hand, which rests on top of the working hand. Pretreatment: lateral neck (abbreviated; see lateral neck sequence, steps 1–3) 1. Center of the abdomen, over the umbilicus (this placement should be avoided if a pulsating aorta is felt with the soft and passive hand) 2. Below and parallel with the thoracic cage on the contralateral side 3. Above and parallel with the inguinal ligament on the contralateral side 4. Repeat step 2 5. Repeat step 1 6. Below and parallel with the thoracic cage on the ipsilateral side 7. Above and parallel with the inguinal ligament on the ipsilateral side 8. Repeat step 6 9. Repeat step 1 Selected indications: postsurgical and post-traumatic swellings (including edema caused by immobility due to partial or complete paralysis); reflex sympathetic dystrophy; rheumatoid arthritis; lipedema; general increase in lymph circulation, or to achieve a common soothing effect by decreasing sympathetic activity Pretreatment: lateral neck (abbreviated; see lateral neck sequence, steps 1–3 and 6 shoulder collectors) Patient in supine position; therapist on the patient’s side ipsilateral to the involved quadrant (in sequence 1–3, the therapist stands next to the patient’s head): 1. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes Stationary circles on the axillary lymph nodes in 2 hand placements; the hand closer to the patient’s head is working, the other hand holds the arm in proper elevated position 2. Effleurage, 2 or 3 times covering the entire arm 3. Manipulation of the medial aspect of the upper arm Stationary circles with the hand closer to the patient’s head, beginning on the medial epicondyle. Several hand placements are applied to cover the medial upper arm, with the working phase direction toward the axillary lymph nodes. The other hand holds the patient’s arm in a comfortable and elevated position. 4. Manipulation of the tissues covering the anterior and posterior portion of the deltoid muscle Stationary circles bimanually and alternating on the anterior and posterior portion of the deltoid muscle; the working phase is directed toward the axillary lymph nodes Note: In the treatment of upper extremity lymphedema, the working phase of this sequence is directed toward the AAA and PAA anastomoses (Fig. 5.13) 5. Manipulation of the lateral aspect of the upper arm Pump technique, with the hand closer to the patient’s head on the lateral upper arm in several placements from the lateral epicondyle toward the acromion. The other hand holds the patient’s arm in a comfortable and elevated position. Combination of pump technique and stationary circle (alternating hands) on the lateral aspect of the upper arm, beginning at the lateral epicondyle in several hand placements toward the olecranon 6. Manipulation of the antecubital fossa Thumb circles (one hand or alternating) covering the antecubital fossa from ~5 cm below to ~5 cm above. Several pathways are applied to cover the antecubital fossa from distal to proximal. This area can also be treated using stationary circles with the palmar surfaces of the fingers. 7. Manipulation of the forearm Scoop techniques with one hand on the anterior and posterior aspect of the forearm between the wrist and the elbow. To manipulate both aspects with the same hand, the patient’s forearm is rotated in pronation and supination, respectively. The other hand holds the patient’s arm at the wrist in a comfortable and elevated position. Combination of pump technique and stationary circles between the wrist and the elbow to cover the patient’s anterior and posterior aspects of the forearm. The patient’s forearm is rotated in pronation and supination, respectively, to cover both surfaces. 8. Manipulation of the dorsum of the hand and wrist Thumb circles (one thumb or alternating) over dorsum of the hand and posterior wrist, starting on the metacarpophalangeal (MP) joints, ending at the styloid processes 9. Manipulation of the palmar aspect of the hand and the anterior wrist (Fig. 5.14) Thumb circles (one thumb or alternating) in the palm, following the ulnar and radial bundle from the center of the palm toward the ulnar and radial edges of the hand (following the path of the collectors) 10. Manipulation of the fingers Combination of thumb/finger circles on each individual finger from the distal to the proximal ends 11. Rework Appropriate techniques are used (depending on the patient’s condition) covering specific parts of the limb or the entire extremity to increase lymph angiomotoricity 12. Final effleurage (as in 2) Selected indications: postsurgical (joint replacement, etc.) and post-traumatic swellings (including edema caused by immobility due to partial or complete paralysis); chronic venous insufficiency stages II and III (phlebo-lymphostatic edema); lipedema; part of the treatment sequence for primary lymphedema of the genitalia; part of the treatment for cyclic idiopathic edema; general increase in lymph circulation, or to achieve a common soothing effect by decreasing sympathetic activity Pretreatment: lateral neck (abbreviated; see lateral neck sequence, steps 1–3), abdomen Patient in supine position, with the leg slightly abducted and externally rotated; therapist on the patient’s involved side: 1. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes Stationary circles with both hands at the same time, with the working phase directed toward the inguinal ligament; 3 hand placements in the medial femoral triangle (Fig. 5.15) First hand placement: the upper hand lies parallel to the inguinal ligament (the fifth metacarpophalangeal joint is aligned with the patient’s ASIS), the lower hand is positioned diagonally to the upper hand (with the fingertips touching the inguinal ligament) Second hand placement: the same hand positions are applied on the medial thigh (medial aspect of the femoral triangle) Third hand placement: both hands lie parallel on the medial aspect of the thigh (sagittal plane) to address the lymph nodes located in the distal apex of the medial femoral triangle 2. Effleurage, 2 or 3 times covering the entire leg 3. Manipulation of the anterior thigh Alternating pump techniques following the rectus femoris muscle between the base of the patella and the ASIS 4. Manipulation of the anterior and lateral thigh Combinations of pump techniques and stationary circles with alternating hands, beginning at the knee to proximal. The lateral pathway follows the iliotibial tract; the anterior pathway follows the rectus femoris muscle. 5. Manipulation of the medial thigh Stationary circles alternating and dynamic at the medial thigh, beginning at the medial aspect of the knee to the groin (sagittal plane) 6. Manipulation of the knee Pump technique in several hand placements (3 or 4) covering the anterior knee Stationary circles (dynamic and simultaneously) on the medial and lateral knee, covering the knee from distal to proximal Stationary circles in several hand placements covering the popliteal fossa from distal to proximal Stationary circles (bimanual and simultaneous) below the medial aspect of knee (“bottleneck” area) 7. Manipulation of the lower leg Scoop technique alternating at the calf between the malleoli and the popliteal fossa (patient’s knee is flexed). Either hand can be used by the therapist. Pump technique on the anterior aspect of the lower leg, scoop technique on the calf (alternating and dynamic), between the malleoli and the knee 8. Manipulation on the foot Stationary circles (simultaneous and dynamic) between the malleoli and the Achilles tendon in several hand placements Thumb circles (1 thumb or alternating) covering the dorsum of the foot and the ankle. Thumb circles may start on the toes or the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints. 9. Rework Appropriate techniques are used (depending on the patient’s condition), covering specific parts of the limb, or the entire extremity to increase lymph angiomotoricity 10. Final effleurage (as in step 2) The treatment of the posterior leg with the patient in the prone position is recommended in those cases where the decongestion of the limb does not advance as expected (“stubborn legs”) with the treatment in supine, or if the swelling is more distally emphasized (e.g., larger swelling on the lower leg). The techniques on the posterior leg are similar to the sequences for the anterior leg (Figs. 5.16 and 5.17). Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes in the supine position precedes the treatment of the posterior leg (Fig. 5.15). Patient in prone position, with the leg slightly abducted; therapist on the patient’s same side: 1. Effleurage, 2 or 3 times covering the entire leg 2. Manipulation of the posterior thigh Alternating pump techniques between the popliteal fossa and the horizontal gluteal fold (frontal plane) 3. Manipulation of the medial thigh Stationary circles alternating and dynamic at the medial thigh, beginning at the medial aspect of the knee to the groin (sagittal plane) 4. Manipulation of the posterior and lateral thigh Combinations of pump techniques and stationary circles with alternating hands, beginning at the popliteal fossa to proximal. The lateral pathway follows the iliotibial tract; the posterior pathway follows the posterior thigh musculature in a frontal plane. 5. Manipulation of the knee Stationary circles or pump techniques covering the popliteal fossa from distal to proximal (3 or 4 hand placements) Stationary circles (bimanual and simultaneous) below the medial aspect of knee (“bottleneck” area) 6. Manipulation of the lower leg Alternating pump techniques in several hand placements covering the calf musculature between the heel and the popliteal fossa Combination of pump techniques and stationary circles covering the calf musculature between the heel and the popliteal fossa in several hand placements Thumb circles (1 thumb or alternating) between the malleoli and the Achilles tendon. To include joint and muscle pump functions, this technique can be combined with passive ankle movements. 7. Rework Appropriate techniques are used (depending on the patient’s condition) covering specific parts of the limb, or the entire extremity to increase lymph angiomotoricity 8. Final effleurage (as in step 1) In the treatment of lymphedema, in particular in those cases where lymph node groups are removed and/or irradiated, some of the sequences outlined above in Application of Basic MLD Techniques on Different Parts of the Body, are modified. These modifications are noted in the appropriate sections in the text. In many cases of extremity lymphedema, the ipsilateral truncal quadrant (this may include the external genitalia) is also congested. Lymphedema affecting the chest, breast, and posterior thorax, also known as truncal lymphedema, is a common problem following breast cancer surgery, but is often difficult to diagnose, especially if the patient does not also present with lymphedema of the arm, or it may be dismissed as a side effect of breast cancer surgery, which will resolve by itself over time. While truncal lymphedema is often not reported or is poorly documented, and available studies are not easy to compare, the literature suggests an incidence of up to 70% of lymphedema affecting the trunk and/or breast following breast cancer treatment. Given the fact that the breast, anterior and posterior thorax, and the upper extremity share the axillary nodes as regional lymph nodes (see Figs. 1.7, 1.8, and 1.17), it is predictable that disruption of lymphatic drainage pathways by partial or complete removal of axillary lymph nodes, with or without radiation therapy, can cause the onset of swelling in the chest wall and breast on the same side. The swelling can either be subtle or quite obvious in presentation and may be present with or without swelling in the arm. The disruption of the natural lymphatic drainage pattern is further complicated by scars on the upper trunk wall following lumpectomy, mastectomy, and reconstructive breast surgery, biopsies or drain sites. Fibrotic tissues in the chest wall or armpit following radiation treatments may further inhibit sufficient lymphatic drainage. Certain breast reconstructive procedures, such as the TRAM-flap reconstruction also disrupt lymphatic drainage in the abdominal area, which may cause the onset of additional swelling in the lower truncal (abdominal) area. Like lymphedema in the extremities, swelling affecting the breast, chest and posterior thorax is typically asymmetrical in appearance if compared with the other side (Fig. 5.18). However, there are often other symptoms present prior to the onset of visible swelling, which can include altered sensation (numbness, tingling, diffuse fullness and pressure, heat), pain, and decreased shoulder mobility. Once lymphedema is visibly present, the swelling can include the entire thorax wall, or it can be localized to the armpit, the scapula, the area over the clavicle or around mastectomy or lumpectomy scar lines, around the reconstructed breast or implants, or it may be limited to the breast tissue only. The breast in patients who have undergone lumpectomy or reconstructive surgery may be larger and heavier, or the shape and height of the breast tissue may change due to fibrotic tissue, resulting in added psychological distress due to problems involving clothing, bra fitting, and body image issues. Postoperative swelling following breast cancer surgery is to be expected and generally lasts up to about 3 months; it appears almost immediately following surgery and places additional stress on the lymphatic system by contributing to the lymphatic workload. The difference between “normal” postoperative edema and lymphedema is its perseverance following the completion of treatment, and the presence of changes in tissue texture, such as lymphostatic fibrosis. While several methods are available to assess truncal and breast edema (skinfold calipers, bioimpedance), subjective examination of the anterior and posterior aspect of the thorax and breast focused on the observation of signs of swelling (asymmetry, bra strap and seam indentations, orange peel phenomenon, changes in skin color), palpation of the tissue texture, and comparison of skinfolds between the affected and nonaffected sides remain the most practical means for assessment of lymphedema affecting the trunk. Serial photographs depicting the anterior and posterior view are helpful tools in assessing changes before and after treatment. Most of the symptoms associated with truncal lymphedema can be treated successfully with complete decongestive therapy. Treatment may be necessary only during the initial period following breast cancer treatment to facilitate edema removal and wound healing, or it may be applied at a later point; truncal lymphedema with or without the involvement of the arm may appear at any time following surgery for breast cancer. Manual Lymph Drainage: Due to the fact that truncal involvement is difficult to identify, particularly if obesity is a factor, it is recommended to generally assume truncal involvement in extremity lymphedema, in which case the decongestion of the involved trunk has priority over the treatment of the swollen extremity, and the truncal preparation is more complex. MLD techniques concentrate on the neck, the anterior and posterior aspects of the upper trunk, as well as the inguinal lymph nodes, followed by techniques focused to redirect lymphatic fluid from congested areas into areas with sufficient lymphatic drainage. If necessary, additional techniques aimed to soften fibrotic tissues may also be applied. The treatment sequences listed under “unilateral secondary upper extremity lymphedema” are based on this assumption. Once the adjacent truncal quadrant is successfully decongested (this is generally the case if volume reduction in the involved extremity is noted), the treatment of the lymphedematous extremity becomes the priority, and the truncal preparation may be abbreviated. For patients who have undergone TRAM-flap procedures, careful attention should be given to address scar tissue that could lead to trapping of lymphatic fluid. During the initial stages of the treatment, patients should be instructed in self-MLD (see page 320) and encouraged to perform self-treatment for at least 20–30 minutes daily. Skin care: Areas between skinfolds on the trunk or the underside of the breast are particularly prone to skin damage and infections. Edematous areas should be kept clean and dry and suitable ointments or lotions formulated for sensitive skin, radiation dermatitis, and lymphedema should be applied (refer to Chapter 4, Skin and Nail Care, for more information on skin care). Exercises: Truncal lymphedema is often associated with restrictions in thorax and shoulder movements, which should be evaluated by a physical therapist. Specific exercises addressing these issues and to increase range of motion and function with daily activities should be performed. Depending on the location and quality of scars, mobilization of adherent scar tissue by a qualified therapist may be necessary to improve range of motion. Breathing and aerobic exercises further facilitate decongestion by improving drainage in superficial and deep lymphatic pathways. Compression therapy: Frequently, compression of the affected area may be challenging due to tenderness of the tissue, or irritated skin secondary to radiation therapy. However, to address fluid accumulation and to avoid worsening of the swelling, the application of compression bandages and/or compression bras or vests is very important. Compression bandages are applied circumferentially around the chest with special care not to impair blood supply to grafts and/or healing scars. Due to the lack of muscle pump activity in the truncal area, the use of wide-width (15–20 cm) medium and long-stretch bandages is preferable over the normally used short-stretch bandages for lymphedema affecting the extremities. Custom-cut or commercially manufactured foam pads (Fig. 5.19) or foam chips may be inserted underneath the bandages or compression bra or vest to increase localized pressure in areas of excess fluid pooling, or to soften localized fibrotic tissue. Flat foam pieces can be used to shape and stabilize the compression bandages and to distribute the pressure evenly over a greater surface area. The patient should be fitted with a specially designed lymphedema bra (see Fig. 5.197) or compression vest following decongestion of the trunk to assist with maintaining the positive results of CDT. Compression bras and vests have minimal seams and wide straps, are available as off-the-shelf or custom-made garments, and ensure that the trunk and breast tissues are properly supported. Compression bras and vests should fit comfortably, provide sufficient support around the trunk and not squeeze breast tissue; pockets to accommodate a prosthesis can be sewn into these garments. Patients using regular bras or sports bras should make sure to avoid narrow bra straps and obtain bra strap pads or wideners, if necessary, to avoid restriction of lymphatic pathways on the shoulder. This condition is most often the result of mastectomy or lumpectomy with the removal and/or irradiation of the axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer surgery. The following sequence should be used until the truncal quadrant is decongested (Fig. 5.20). Patient in supine position: 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes, including the shoulder collectors (observe contraindications) 2. Activation of the axillary lymph nodes on the contralateral side. Anterior thorax on the contralateral side (omit intercostal and parasternal techniques) 3. Activation and utilization of the AAA anastomosis to move lymph fluid from the affected to the unaffected side 4. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on the ipsilateral, affected side Therapist moves to other side of table: 5. Activation and utilization of the AI anastomosis on the affected side 6. Manipulation of lymph fluid from the congested upper quadrant in the direction of the inguinal lymph nodes on the same side, utilizing the AI anastomosis. Rotary techniques and stationary circles should be used. 7. Intercostal and parasternal techniques on the affected trunk quadrant to utilize deep drainage pathways Patient on the side (or prone position), with the affected extremity on top: 8. Rework of the AI anastomosis and shoulder collectors Patient in prone position (or on the side): 9. Posterior thorax on the unaffected side (omit intercostal and paravertebral techniques) 10. Activation and utilization of the PAA anastomosis to move lymph fluid from the affected to the unaffected side. Stationary circles should be used. Therapist moves to other side of table: 11. Manipulation of lymph fluid from the congested posterior upper quadrant in the direction of the inguinal lymph nodes on the same side, utilizing the AI anastomosis. Rotary techniques and stationary circles should be used. Patient on the side (or prone position), with the affected extremity on top: 13. Rework of PAA anastomosis, AI anastomosis, and shoulder collectors Patient in supine position: 14. Rework of AAA anastomosis, axillary lymph nodes on the contralateral side, and inguinal lymph nodes on the ipsilateral side 15. Application of compression bandages on the involved extremity The following sequence should be used if the truncal quadrant is decongested and the treatment of the upper extremity is the primary focus: Patient in supine position. Abbreviated trunk preparation (pretreatment): 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes, including the shoulder collectors (observe contraindications) 2. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes on the contralateral side 3. Activation and utilization of the AAA anastomosis to stimulate lymph flow from the affected to the unaffected side 4. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on the ipsilateral (affected) side Therapist moves to other side of table: 5. Activation and utilization of the AI anastomosis on the affected side to stimulate lymph flow toward the drainage area Patient on the side (or prone position), with the affected extremity on top: 6. Rework of AI anastomosis and shoulder collectors 7. Activation and utilization of the PAA anastomosis to stimulate lymph flow from the affected to the unaffected side If the upper extremity is considerably swollen, it is not recommended to treat the entire extremity during a single session. The treatment should proceed in steps; for example, only the upper arm (or parts of it) may be treated, which prevents overload of the healthy lymphatics in the drainage areas. 8. Manipulation of the lateral upper arm between the lateral epicondyle and the acromion, using basic techniques (“bulk flow” techniques) 9. Rework of shoulder collectors, AI and PAA anastomosis Patient in supine position: 10. Rework of AAA anastomosis 11. Manipulation of the lateral upper arm between the lateral epicondyle and the acromion. Modified effleurage as well as pump techniques and combination of pump and stationary circles should be used (see sequence 4–5, upper arm). This sequence should be followed up with rework techniques across the watershed into pretreated drainage areas. 12. Manipulation of the medial aspect of the upper arm toward the lateral aspect, using stationary circles (dynamic technique). This technique should be followed up with rework techniques of drainage areas as in step 11. The entire length of the upper arm is treated in this manner. 13. Vasa vasorum technique in the area of the cephalic vein (see Fig. 4.9) 14. Manipulation of elbow, forearm, and hand as outlined in the basic sequence techniques 15. If necessary, edema or fibrosis techniques should be incorporated at this point 16. Rework of upper extremity, AAA anastomosis, axillary lymph nodes on contralateral side, inguinal lymph nodes on ipsilateral side, and shoulder collectors Patient on the side (or prone position), with the affected extremity on top: 17. Rework of the PAA and AI anastomoses (on the same side) 18. Application of compression bandages on involved extremity This condition is most often the result of mastectomy or lumpectomy with the removal and/or irradiation of the axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer surgery. Ideally, bandages should be applied on both upper extremities. If this is not possible, compression bandages should be applied to the more involved extremity. The following sequence should be used until the truncal quadrant(s) is/are decongested (Fig. 5.21). Patient in supine position: 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes, including the shoulder collectors (observe contraindications) 2. Abdominal treatment: superficial and deep (modified) techniques as outlined in the basic sequences (observe contraindications). If abdominal techniques are contraindicated, diaphragmatic breathing should be used to substitute. 3. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on both sides 4. Activation and utilization of the AI anastomoses on both sides to promote lymph flow from the congested quadrants to the drainage areas 5. Manipulation of lymph fluid from the congested upper quadrants in the direction of the inguinal lymph nodes, utilizing the AI anastomoses. Rotary techniques and stationary circles should be used. 6. Intercostal and parasternal techniques on both affected trunk quadrants to utilize deep drainage pathways Patient in prone position (or on side): 7. Rework of both AI anastomoses 8. Manipulation of lymph fluid from the congested posterior upper quadrants in the direction of the inguinal lymph nodes, utilizing the AI anastomoses. Dynamic rotary techniques and stationary circles should be used. 9. Intercostal and paravertebral techniques on both affected trunk quadrants to utilize deep drainage pathways Patient in supine position: 10. Rework of AI anastomoses on both sides, deep abdominal technique (modified), inguinal lymph nodes on both sides, and shoulder collectors 11. Application of compression bandages on both, or the more involved extremity The following sequence should be used if the truncal quadrant(s) is/are decongested and the treatment of the upper extremities becomes the primary focus. It is not recommended to treat both extremities in the same session. The more involved extremity should be treated first until decongested, then fitted with a compression sleeve. If the extremity is considerably swollen, it should be treated in steps; for example, only the upper arm (or parts of it) should be treated, which prevents overload of the healthy lymphatics in the drainage areas. Therapy proceeds with the other arm, once the more involved extremity is decongested. Patient in supine position: 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes, including the shoulder collectors (observe contraindications) 2. Deep abdominal technique (modified) as outlined in the basic sequence (observe contraindications). If abdominal techniques are contraindicated, diaphragmatic breathing should be used to substitute. 3. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on both sides 4. Activation and utilization of the AI anastomoses on both sides to promote lymph flow across the watersheds into the drainage areas Patient on the side (or prone position), with the more involved extremity on top: 5. Rework of AI anastomosis on the more involved side, and the shoulder collectors 6. Manipulation of the lateral upper arm between the lateral epicondyle and the acromion, using basic techniques (“bulk flow” techniques) 7. Rework of shoulder collectors and AI anastomosis on more involved side Patient in supine position: 8. Manipulation of the lateral upper arm (more involved extremity) between the lateral epicondyle and the acromion. Modified effleurage as well as pump techniques and combination of pump and stationary circles should be used (see sequence 4–5, upper arm). This sequence should be followed up with rework techniques across the watershed into pretreated drainage areas. 9. Manipulation of the medial aspect of the upper arm toward the lateral aspect, using stationary circles (dynamic technique). This technique should be followed up with rework techniques of drainage areas. The entire length of the upper arm is treated in this manner. 10. Vasa vasorum technique in the area of the cephalic vein 11. Manipulation of elbow, forearm, and hand as outlined in the basic sequence techniques 12. If necessary, edema or fibrosis techniques should be incorporated at this point. 13. Rework of upper extremity, inguinal lymph nodes on both sides, AI anastomoses on both sides, shoulder collectors, and deep abdominal technique (modified) 14. Application of compression bandages on both, or the more involved extremity This condition is most often the result of the removal and/or irradiation of the inguinal and/or pelvic lymph nodes in cancer surgery (prostate, bladder, female reproductive organs, melanoma). Secondary lower extremity lymphedema may also occur as a result of trauma and may be combined with swelling of the lower truncal quadrant on the same side, and/or the external genitalia. The following sequence should be used until the truncal quadrant is decongested (Fig. 5.22). Patient in supine position: 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes (observe contraindications) 2. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes on the ipsilateral side 3. Activation and utilization of the IA anastomosis to move lymph fluid from the swollen lower quadrant toward the drainage area 4. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on the contralateral side 5. Activation and utilization of the AII anastomosis to move lymph fluid from the swollen lower quadrant toward the drainage area on the opposite side 6. Abdominal treatment: superficial and deep (modified) techniques as outlined in the basic sequences (observe contraindications). If abdominal techniques are contraindicated, diaphragmatic breathing should be substituted. Patient on the side (or prone position), with the affected extremity on top: 7. Rework of the IA anastomosis on the affected side Patient in prone position (or on side): 8. Manipulation of the lumbar area on the unaffected side (omit step 4) 9. Activation and utilization of the PII anastomosis to move lymph fluid from the swollen lower quadrant toward the drainage area on the opposite side 10. Paravertebral techniques on the affected lumbar area to promote deep lymphatic pathways 11. Rework of the PII anastomosis Patient in supine position: 12. Rework of AII anastomosis, IA anastomosis on the affected side, inguinal lymph nodes on contralateral and axillary lymph nodes on ipsilateral sides, and deep abdominal techniques (modified) 13. Application of compression bandages on the affected extremity The following sequence should be used if the truncal quadrant is decongested and the treatment of the lymphedematous leg is the primary focus. Patient in supine position. Abbreviated trunk preparation (pretreatment): 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes (observe contraindications) 2. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes on the ipsilateral side 3. Activation and utilization of the IA anastomosis to promote lymph flow across the watershed toward the drainage area 4. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on the contralateral side 5. Activation and utilization of the AII anastomosis to promote lymph flow across the watershed toward the drainage area on the opposite side 6. Deep abdominal technique (modified) as outlined in the basic sequences (observe contraindications). If abdominal techniques are contraindicated, diaphragmatic breathing should be substituted. Patient on the side (or prone position), with the affected extremity on top: 7. Rework of the IA anastomosis on the affected side 8. Activation and utilization of the PII anastomosis to promote lymph flow across the watershed toward the drainage area on the opposite side 9. Manipulation of the lateral thigh between the lateral knee and the iliac crest, using basic techniques (“bulk flow” techniques) 10. Rework of the PII and IA anastomoses (on the affected side) Patient in supine position: 11. Rework of the AII anastomosis If the lower extremity is considerably swollen, it is not recommended to treat the entire extremity in a single session. The treatment should proceed in steps; for example, only the thigh (or parts of it) should be treated, which prevents overload of the healthy lymphatics in the drainage areas. 12. Manipulation of the lateral thigh between the knee and the iliac crest. Modified effleurage as well as pump techniques, combination of pump and stationary circles, and rotary techniques should be used. This sequence should be followed up with rework techniques across the watersheds into pretreated drainage areas. 13. Manipulation of the medial aspect of the thigh toward the lateral aspect, using stationary circles (dynamic technique). This technique should be repeated over the entire length of the thigh and followed up with rework techniques toward the drainage areas. 14. Vasa vasorum technique in the area of the femoral vein 15. Manipulation of knee, lower leg, and foot as outlined in the basic sequence techniques 16. If necessary, edema or fibrosis techniques should be incorporated at this point. It may also be necessary to turn the patient into the prone position for the treatment of the posterior leg. 17. Rework of lower extremity, AII anastomosis, IA anastomosis on the affected side, axillary lymph nodes on ipsilateral side, inguinal lymph nodes on contralateral side, and deep abdominal techniques (modified) Patient on the side (or prone position), with the affected extremity on top: 18. Rework of the PII anastomosis 19. Application of compression bandages on the affected extremity This condition is most often the result of the removal and/or irradiation of the inguinal and/or pelvic lymph nodes in cancer surgery (prostate, bladder, female reproductive organs, melanoma). Secondary lower extremity lymphedema may also occur as a result of trauma and may be combined with swelling of the lower truncal quadrant on the same side, and/or the external genitalia. Ideally, bandages should be applied on both lower extremities. If this is not possible, compression bandages should be applied to the more involved extremity. The following sequence should be used until the truncal quadrant(s) is/are decongested (Fig. 5.23). Patient in supine position: 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes (observe contraindications) 2. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes on both sides 3. Activation and utilization of the IA anastomoses on both sides to promote lymph flow from the congested quadrants to the drainage areas 4. Abdominal treatment: superficial and deep (modified) techniques as outlined in the basic sequences (observe contraindications). If abdominal techniques are contraindicated, diaphragmatic breathing should be substituted. Patient in prone position (or on side): 5. Rework of IA anastomoses on both sides 6. Decongestion of the swollen lower truncal quadrants on both sides toward the axillary lymph nodes, using modified lumbar techniques: modified effleurage; rotary techniques starting at the sagittal watershed to the side, followed by stationary circles (dynamic technique) toward the axilla using the IA anastomosis; paravertebral techniques to utilize deep drainage pathways Patient in supine position: 7. Rework of IA anastomoses and axillary lymph nodes on both sides 8. Rework abdominal area: superficial and deep (modified) techniques 9. Application of compression bandages on both or the more involved extremity It is not recommended to treat both extremities in the same session. The more involved extremity should be treated first until decongested. If the extremity is considerably swollen, it should be treated in steps; for example, only the thigh (or parts of it) should be treated, which prevents overload of the healthy lymphatics in the drainage areas. Therapy proceeds with the other leg, once the more involved extremity is decongested. Generally, a pantyhose-style compression garment is ideal for this condition once both extremities are decongested. To preserve the results in the leg that was treated first, compression bandages should be applied. If this is not possible, the patient should be fitted with a thigh-high compression garment (preferably a relatively inexpensive standard-size garment) while the other extremity receives treatment, then he or she should be fitted with a pantyhose-style garment. Patient in supine position. Abbreviated trunk preparation (pretreatment): 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes (observe contraindications) 2. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes on both sides 3. Activation and utilization of the IA anastomoses on both sides to promote lymph flow across the watersheds into the drainage areas 4. Abdominal treatment: superficial and deep (modified) techniques as outlined in the basic sequences (observe contraindications). If abdominal techniques are contraindicated, diaphragmatic breathing should be substituted. Patient on the side (or prone position), with the more involved extremity on top: 5. Rework of the IA anastomosis on the more involved side 6. Manipulation of the lateral thigh between the lateral knee and the iliac crest, using basic techniques (“bulk flow” techniques) Patient in supine position: 7. Rework of IA anastomoses on both sides Treatment of the lower extremity: 8. Manipulation of the lateral thigh between the knee and the iliac crest. Modified effleurage as well as pump techniques, combination of pump and stationary circles, and rotary techniques should be used. This sequence should be followed up with rework techniques across the watersheds into pretreated drainage areas. 9. Manipulation of the medial aspect of the thigh toward the lateral aspect, using stationary circles (dynamic technique). This technique should be repeated over the entire length of the thigh and followed up with rework techniques toward the drainage areas. 10. Vasa vasorum technique in the area of the femoral vein 11. Manipulation of knee, lower leg, and foot as outlined in the basic sequence techniques 12. If necessary, edema or fibrosis techniques should be incorporated at this point. It may also be necessary to turn the patient into the prone position for the treatment of the posterior leg. 13. Rework of lower extremity, IA anastomoses on both sides, axillary lymph nodes on both sides, and abdominal techniques 14. Application of compression bandages on both, or the more involved extremity This condition is the result of developmental abnormalities (see Chapter 3, Primary Lymphedema) of the lymphatic system, which are either congenital or hereditary. Primary lower extremity lymphedema may be combined with swelling of the adjacent truncal quadrant and/or the external genitalia. Congenital malformations of the lymphatic system may also be present in the contralateral leg. If the volume of the unaffected leg increases, or if any changes in tissue consistency are noted during the treatment, the use of interinguinal anastomoses (AII and PII) should be discontinued. Treatment sequences for this condition are very similar to the treatment of secondary lymphedema of the lower extremity. The inguinal lymph nodes in primary lymphedema are still present and should be stimulated. The goal of intervention, however, is to relieve these lymph nodes; lymph fluid is therefore rerouted around the inguinal lymph nodes toward sufficient drainage areas located in the adjacent trunk territories. The following sequence should be used until the truncal quadrant is decongested (Fig. 5.22). Patient in supine position: 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes (observe contraindications) 2. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes on the ipsilateral side 3. Activation and utilization of the IA anastomosis to move lymph fluid from the swollen lower quadrant toward the drainage area 4. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on the contralateral side 5. Activation and utilization of the AII anastomosis to move lymph fluid from the swollen lower quadrant toward the drainage area on the opposite side 6. Abdominal treatment: superficial and deep (modified) techniques as outlined in the basic sequences (observe contraindications). If abdominal techniques are contraindicated, diaphragmatic breathing should be substituted. Therapist moves to the other side of the treatment table: 7. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on the affected side Patient in prone position (or on side): 8. Manipulation of the lumbar area on the unaffected side (omit manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes) 9. Activation and utilization of the PII anastomosis to move lymph fluid from the swollen lower quadrant toward the drainage area on the opposite side 10. Paravertebral techniques on the affected lumbar area to promote deep lymphatic pathways 11. Rework of the PII anastomosis Patient in supine position: 12. Rework of AII anastomosis, IA anastomosis on the affected side, axillary lymph nodes on the ipsilateral side, inguinal lymph nodes on both sides, and deep abdominal techniques (modified) 13. Application of compression bandages on the affected extremity The following sequence should be used if the truncal quadrant is decongested and the treatment of the lymphedematous leg is the primary focus. Patient in supine position. Abbreviated trunk preparation (pretreatment): 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes (observe contraindications) 2. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes on the ipsilateral side 3. Activation and utilization of the IA anastomosis to promote lymph flow across the watershed toward the drainage area 4. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on the contralateral side 5. Activation and utilization of the AII anastomosis to promote lymph flow across the watershed toward the drainage area on the opposite side 6. Deep abdominal technique (modified) as outlined in the basic sequences (observe contraindications). If abdominal techniques are contraindicated, diaphragmatic breathing should be substituted. Patient on the side (or prone position), with the affected extremity on top: 7. Rework of the IA anastomosis on the affected side 8. Activation and utilization of the PII anastomosis to promote lymph flow across the watershed toward the drainage area on the opposite side 9. Manipulation of the lateral thigh between the lateral knee and the iliac crest, using basic techniques (“bulk flow” techniques) 10. Rework of the PII and inguinal-axillary anastomoses (on the affected side) Patient in supine position: 11. Rework of the AII anastomosis If the lower extremity is considerably swollen, it is not recommended to treat the entire extremity in one session. The treatment should proceed in steps; for example, only the thigh (or parts of it) may be treated, which prevents overload of the healthy lymphatics in the drainage areas. If the swelling is more distally pronounced (as is often the case in primary lymphedema), more time should be spent treating the areas below the knee. 12. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on the affected leg As discussed earlier, inguinal lymph nodes in primary lymphedema are used as additional drainage areas. Lymph fluid from more distal sections of the leg should not be manipulated toward the inguinal nodes but rerouted around them as in the treatment of secondary lymphedema. 13. Manipulation of the lateral thigh between the knee and the iliac crest Modified effleurage as well as pump techniques, combination of pump and stationary circles, and rotary techniques should be used. This sequence should be followed up with rework techniques across the watersheds into pretreated drainage areas. 14. Manipulation of the medial aspect of the thigh toward the lateral aspect, using stationary circles (dynamic technique). This technique should be repeated over the entire length of the thigh and followed up with rework techniques toward the drainage areas. 15. Vasa vasorum technique in the area of the femoral vein 16. Manipulation of knee, lower leg, and foot as outlined in the basic sequence techniques 17. If necessary, edema or fibrosis techniques should be incorporated at this point. It may also be necessary to turn the patient into the prone position for the treatment of the posterior leg. 18. Rework of lower extremity, including the inguinal lymph nodes; rework of the anterior AII anastomosis, IA anastomosis on the affected side, axillary lymph nodes on ipsilateral side, inguinal lymph nodes on the contralateral side, and deep abdominal techniques (modified) Patient on the side (or prone position), with the affected extremity on top: 19. Rework of the PII anastomosis 20. Application of compression bandages on the affected extremity This condition is the result of developmental abnormalities (see Chapter 3, Primary Lymphedema) of the lymphatic system, which are either congenital or hereditary. Primary lower extremity lymphedema may be combined with swelling of the adjacent truncal quadrant and/or the external genitalia. Treatment sequences for this condition are very similar to the treatment of bilateral secondary lymphedema of the lower extremities. The inguinal lymph nodes in primary lymphedema are still present and should be stimulated. The goal of intervention, however, is to relieve these lymph nodes; lymph fluid is therefore rerouted around the inguinal lymph nodes toward sufficient drainage areas located in the upper truncal territories (axillary lymph nodes). The following sequence should be used until the truncal quadrant(s) is/are decongested (Fig. 5.23). Patient in supine position: 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes (observe contraindications) 2. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes on both sides 3. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on both sides 4. Activation and utilization of the IA anastomoses on both sides to promote lymph flow from the congested quadrants to the drainage areas 5. Abdominal treatment: superficial and deep (modified) techniques as outlined in the basic sequences (observe contraindications). If abdominal techniques are contraindicated, diaphragmatic breathing should be substituted. Patient in prone position (or on side): 6. Rework of IA anastomoses on both sides 7. Decongestion of the swollen lower truncal quadrants on both sides toward the axillary lymph nodes, using modified lumbar techniques: modified effleurage; rotary techniques starting at the sagittal watershed to the side, followed by stationary circles (dynamic technique) toward the axilla using the IA anastomosis; paravertebral techniques to utilize deep drainage pathways Patient in supine position: 8. Rework of IA anastomoses and axillary lymph nodes on both sides 9. Rework abdominal area: superficial and deep (modified) techniques 10. Application of compression bandages on both or the more involved extremity The following sequence should be used if the truncal quadrant(s) is/are decongested and the treatment of the lower extremities becomes the primary focus. It is not recommended to treat both extremities in the same session. The more involved extremity should be treated first until decongested. If the extremity is considerably swollen, it should be treated in steps; for example, only the thigh (or parts of it) may be treated, which prevents overload of the healthy lymphatics in the drainage areas. Therapy proceeds with the other leg, once the more involved extremity is decongested. Generally, a pantyhose-style compression garment is ideal for this condition, once both extremities are decongested. To preserve the results in the leg that was treated first, compression bandages should be applied. If this is not possible, the patient should be fitted with a thigh-high compression garment (preferably a relatively inexpensive standard-size garment) while the other extremity receives treatment, then be fitted with a pantyhose-style garment. Patient in supine position. Abbreviated trunk preparation (pretreatment): 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes (observe contraindications) 2. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes on both sides 3. Activation and utilization of the IA anastomoses on both sides to promote lymph flow across the watersheds into the drainage areas 4. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on both sides As discussed earlier, inguinal lymph nodes in primary lymphedema are used as additional drainage areas. Lymph fluid from more distal sections of the leg should not be manipulated toward the inguinal nodes, but rerouted around them, as in the treatment of secondary lymphedema (see secondary lower extremity lymphedema). 5. Abdominal treatment: superficial and deep (modified) techniques as outlined in the basic sequences (observe contraindications). If abdominal techniques are contraindicated, diaphragmatic breathing should be substituted. Patient on the side (or prone position), with the more involved extremity on top: 6. Rework of the IA anastomosis on the more involved side 7. Manipulation of the lateral thigh between the lateral knee and the iliac crest, using basic techniques (“bulk flow” techniques) Patient in supine position: 8. Rework of IA anastomoses on both sides Treatment of the lower extremity: 9. Rework the inguinal lymph nodes on the more involved leg 10. Manipulation of the lateral thigh between the knee and the iliac crest Modified effleurage as well as pump techniques, combination of pump and stationary circles, and rotary techniques should be used This sequence should be followed up with rework techniques across the watersheds into pretreated drainage areas 11. Manipulation of the medial aspect of the thigh toward the lateral aspect, using stationary circles (dynamic technique). This technique should be repeated over the entire length of the thigh and followed up with rework techniques toward the drainage areas. 12. Vasa vasorum technique in the area of the femoral vein 13. Manipulation of knee, lower leg, and foot as outlined in the basic sequence techniques 14. If necessary, edema or fibrosis techniques should be incorporated at this point. It may also be necessary to turn the patient into the prone position for the treatment of the posterior leg. 15. Rework of lower extremity, including the inguinal lymph nodes; rework of the IA anastomoses on both sides, axillary lymph nodes on both sides, inguinal lymph nodes on the less swollen leg, and abdominal techniques 16. Application of compression bandages on both, or the more involved extremity Genital lymphedema is a challenging condition that very often causes real and long-lasting physical, emotional, and social problems for the affected patients. This condition can affect both males and females but is more common in males due to the greater tissue elasticity of the scrotum and penis, combined with the effects of gravity (Fig. 5.24). Reliable numbers on the incidence of genital swelling are unavailable because this condition often remains undiagnosed; genital edema is generally not a topic of conversation, unlike swelling of an extremity following surgery. Genital lymphedema is usually irreversible without treatment, and once it develops, it tends to become more fibrotic and increases in size. It can be effectively controlled and maintained with complete decongestive therapy (CDT). In some cases, genital swelling may occur acutely following surgery or trauma and may resolve completely by itself. In most cases genital lymphedema is combined with lower extremity lymphedema. For a detailed discussion of genital lymphedema treatment, see p. 280–291. Fig. 5.24 Genital lymphedema with involvement of the penis in an uncircumcised patient. Arrows indicate drainage directions. Genital swelling can be classified as malignant, benign, primary, and secondary. Advanced pelvic and/or abdominal malignancies may block or reduce the lymphatic and venous return from the genital area. The onset of genital swelling without apparent reason, the presence of a clear vaginal discharge, or lymphorrhea, may be a symptom of an active malignant process and needs to be thoroughly examined by a physician. Primary genital swelling is usually the result of congenital malformations (dysplasia) of lymph vessels and/or lymph nodes in the region. As with all primary forms, the swelling may be present at birth (rare) or develop later in life with or without obvious cause. Minor surgical interventions, such as a circumcision, may trigger the onset of pediatric genital swelling if congenital malformations of the lymphatic system are present. Isolated swelling of the genital region is not common. In many cases other parts of the body are involved in the swelling as well, such as the lower quadrant(s) and/or one or both of the lower extremities. It was also reported that obese patients with lower extremity lymphedema have an increased risk of developing genital swelling due to greater pressure on the lymphatic system in the groin from the enlarged abdomen. Fig. 5.25 Genital lymphedema with lymphatic cysts and fistulas. Arrows indicate drainage directions. Trauma or surgical interventions in combination with the removal and/or irradiation of lymph vessels and/or lymph nodes (especially pelvic lymph nodes) to remove gynecological, testicular, penile, urological, abdominal, intestinal, or prostatic cancers are a common cause. The incidence of genital swelling tends to increase with the combination of surgery and radiation, and if the patient has a history of recurrent episodes of cellulitis. The swelling may occur immediately post surgery or years later as with other forms of lymphedema. Reports suggest that genital swelling in combination with lower extremity lymphedema occurs in ~10% of patients. The incidence of genital swelling in females has been estimated at 10% to 20% of patients following surgery. In males, the incidence of genital edema following oncological surgery (prostatectomy, bladder cancer) and/or irradiation seems to be considerably higher. Filariasis is another common cause of genital swelling in endemic regions (see Chapter 3, Pathology, and Fig. 3.4a, b). A very common reason for the onset of genital swelling is the use of pneumatic compression pumps for the treatment of lower extremity lymphedema. Boris, Weindorf, and Lasinski published a paper in the March 1998 edition of Lymphology and concluded that the use of external pneumatic compression pumps in the treatment of lower extremity lymphedema produces an unacceptable high incidence of genital edema1 (See Chapter 3, Therapeutic Approach to Lymphedema). Various combinations of genital anatomy swelling may occur. In males, isolated penile swelling is rare. Combined penile and scrotal swelling is a more common presentation. The scrotum may swell to such an extent that ambulation becomes difficult. The lower quadrants and/or lower extremities often accompany genital swelling. Additional involvement of the pubic area frequently causes the penis to retract into the scrotum. In females, the labia minora and the labia majora may be included in the swelling. These areas could project several centimeters out of the vagina. Clear labial/vaginal discharge (lymphorrhea), the appearances of papillomas or warty growths are often symptoms indicating genital involvement, especially if the patient had pelvic or gynecological procedures. Vaginal discharge for other reasons is often a curdish, white, thick discharge. Genital swelling frequently causes problems in urination and sexual activity, depending on the extent of the involvement. Other conditions, such as active malignancies, renal, liver, cardiac or venous problems can cause genital edema. A thorough evaluation with a clear diagnostic picture is necessary before MLD/CDT can be initiated. • What kind of surgery (if any) was performed and how many lymph nodes were excised? • Were there any cellulitis attacks in the past? Where did they start? • Pain? Some patients describe bursting sensation or an ache around the genital area (pain generally recedes with treatment). Males often complain about painful erections. • Were/are there any problems with bowel or bladder function following surgery or radiation? • Are appropriate hygienic measures possible? • Is the patient circumcised? • Any moist areas, lymphatic cysts, lymphatic fistulas (Fig. 5.25), lymphorrhea (patients often use sanitary or incontinence pads)? • Extent of the swelling? Penis/scrotum; external/internal labiae; pubic area; lower quadrant and/or lower extremity (unilateral/bilateral) • Scars? • Skinfolds in the genital region? • Papillomas, warts? • Bacterial or mycotic infections? (Patients with discharge from the area often complain about malodor; lymph itself has no odor, but is very high in protein content, which presents an excellent breeding ground for bacteria, causing malodor.) • Tissue quality—fibrosis, scars • Tissue quality in other involved areas • Can the foreskin be pulled back in uncircumcised male patients? As discussed earlier, genital swelling is often associated with lower extremity lymphedema. The treatment of the genital swelling may be included in the treatment sequence or it may be performed as a stand-alone treatment. If lower extremity swelling (or truncal edema) is present, the treatment of the genital swelling should precede the sequence for leg lymphedema. Lymphatic cysts and/or fistulas, lymphorrhea, bacterial and mycotic infections are common complicating factors found in combination with this condition. Meticulous hygiene is therefore imperative. If fistulas are present, the area must be cleaned and disinfected with proper agents, and the treatment should be performed wearing sterile gloves. To maximize the therapeutic effect, genital bandaging may be performed prior to the application of hands-on techniques for the pretreatment of the drainage areas. Following the treatment sequence, the bandages are removed and the MLD techniques in the swollen genital area are performed (see page 283). The therapist then proceeds with the application of the final compression bandage. The application of compression bandages on the genital area is discussed later in this chapter. Patient in supine position: 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes (observe contraindications) 2. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes on both sides 3. Activation and utilization of the IA anastomoses on both sides to promote lymph flow across the watershed into the drainage areas 4. If inguinal lymph nodes are present, manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on both sides 5. Abdominal treatment: superficial and deep (modified) techniques as outlined in the basic sequences (observe contraindications). If abdominal techniques are contraindicated, diaphragmatic breathing should be substituted. If the lower truncal quadrants are congested, the patient is turned into the prone position at this point, and the lumbar areas are decongested in the following manner. Decongestion of the swollen lower truncal quadrants on both sides toward the axillary lymph nodes, using modified lumbar techniques; modified effleurage; rotary techniques starting at the sagittal watershed to the side, followed by stationary circles (dynamic techniques) toward the axilla using the IA anastomosis; paravertebral techniques to utilize deep drainage pathways. The patient is then turned back into the supine position. 6. Treatment of the scrotum: stationary circles on both sides of the scrotum to manipulate the lymph fluid toward the pubic area, and from here toward the axillary lymph nodes on the respective side, utilizing the IA anastomoses. 7. Application of bandages (see Lower Extremity Bandaging, p. 256 and Compression Bandaging for Male Genital Lymphedema, p. 286 later in this chapter) This condition is a result of a venous insufficiency (for pathology, refer to Chapter 3, Chronic Venous and LymphoVenous Insufficiency). The deficient venous valves in chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) fail to prevent retrograde flow of venous blood during muscle pump activity, which in turn directly affects the lymphatic system. Over time, and if CVI is left without treatment, damage to the lymphatic system, combined with reduction in transport capacity is unavoidable. The presence of lymphedema in stages II and III of CVI necessitates the application of the complete spectrum of complete decongestive therapy. If venous ulcerations are present, appropriate wound dressings and skin care products, prescribed by the physician, are applied before CDT starts (refer to Chapter 3, Complete Decongestive Therapy). The wound remains covered during the treatment, and MLD techniques are directed away from and around the ulcer bed. Treatment in and around the wound area is performed wearing sterile gloves. Decongestion of the extremity greatly increases the tendency of venous stasis ulcerations to heal. The treatment protocol for lymphedema associated with CVI corresponds with the protocol for primary lymphedema; fibrosis and edema techniques are contraindicated. Should any signs or symptoms of thrombophlebitis in deep veins or symptoms of pulmonary embolism develop (see Chapter 3, Thrombophlebitis in Deep Veins), the patient must see a doctor immediately, and any treatment must be interrupted until the condition is cleared up. Patient in supine position. Abbreviated trunk preparation (pretreatment): 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes (observe contraindications) 2. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes on the ipsilateral side 3. Activation and utilization of the IA anastomosis to promote lymph flow across the watershed toward the drainage area 4. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on the contralateral side 6. Deep abdominal technique (modified) as outlined in the basic sequences (observe contraindications). If abdominal techniques are contraindicated, diaphragmatic breathing should be substituted. Patient on the side (or prone position), with the affected extremity on top: 7. Rework of the IA anastomosis on the affected side 8. Activation and utilization of the PII anastomosis to promote lymph flow across the watershed toward the drainage area on the opposite side 9. Manipulation of the lateral thigh between the lateral knee and the iliac crest, using basic techniques (“bulk flow” techniques) 10. Rework of the PII and IA anastomosis (on the affected side) Patient in supine position: 11. Rework of the AII anastomosis Treatment of the lower extremity (experience shows that the swelling in phlebolymphostatic edema is generally pronounced more distally; in these cases, more time should be spent treating the tissues distal to the knee joint) 12. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on the affected leg 13. Manipulation of the lateral thigh between the knee and the iliac crest Modified effleurage as well as pump techniques, combination of pump and stationary circles, and rotary techniques should be used. This sequence should be followed up with rework techniques across the watersheds into pretreated drainage areas. 14. Manipulation of the medial aspect of the thigh toward the lateral aspect, using stationary circles (dynamic technique). This technique should be repeated over the entire length of the thigh and followed up with rework techniques toward the drainage areas. 15. Manipulation of knee, lower leg, and foot as outlined in the basic sequence techniques To maximize the decongestive effect, it is often beneficial to turn the patient into the prone position at this point for the treatment of the posterior lower leg 16. Rework of lower extremity, including the inguinal lymph nodes. Rework of the AII anastomosis, IA anastomosis on the affected side, axillary lymph nodes on the ipsilateral side, inguinal lymph nodes on the contralateral side, and deep abdominal techniques (modified) Patient on the side (or prone position), with the affected extremity on top: 17. Rework of the PII anastomosis 18. Application of compression bandages on the affected extremity. In many cases of phlebo-lymphostatic insufficiency, compression bandages need to be applied only up to the knee; this depends on the severity of the swelling and is determined by the physician. Lipolymphedema generally involves both lower extremities, and the treatment protocol of this condition corresponds with that of primary lymphedema. The lymphedematous component responds well and relatively fast to CDT; the lipedema itself responds more slowly, sometimes not at all. Lighter pressures in manual and compression bandage techniques during the initial treatment sessions may be necessary because lipedema and lipolymphedema are often associated with hypersensitivity and pain, which typically diminish after several treatments. Patients often require more padding under the compression bandages, particularly in the anterior tibial area. In some cases, it may be necessary not to apply a bandage at all during the first few treatments. Edema and fibrosis techniques are contraindicated in the treatment of this condition. The following sequence should be used until the truncal quadrant(s) is/are decongested. Patient in supine position: 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes (observe contraindications) 2. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes on both sides 3. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on both sides 4. Activation and utilization of the IA anastomoses on both sides to promote lymph flow from the congested quadrants to the drainage areas 5. Abdominal treatment: superficial and deep (modified) techniques as outlined in the basic sequences (observe contraindications). If abdominal techniques are contraindicated, diaphragmatic breathing should be substituted. Patient in prone position (or on side): 6. Rework of IA anastomoses on both sides 7. Decongestion of the swollen lower truncal quadrants on both sides toward the axillary lymph nodes, using modified lumbar techniques: modified effleurage; rotary techniques starting at the sagittal watershed to the side, followed by stationary circles toward the axilla using the IA anastomosis (IA); paravertebral techniques to utilize deep drainage pathways 8. Rework of IA anastomoses and axillary lymph nodes on both sides 9. Rework abdominal area: superficial and deep (modified) techniques 10. Application of compression bandages on both, or the more involved extremity The following sequence should be used if the truncal quadrant(s) is/are decongested and the treatment of the lower extremities becomes the primary focus. It is not recommended to treat both extremities in the same session. The more involved extremity should be treated first until decongested. If the extremity is considerably swollen, it should be treated in steps; for example, only the thigh (or parts of it) may be treated, which prevents overload of the healthy lymphatics in the drainage areas. Therapy proceeds with the less involved leg, once the more involved extremity is decongested. Generally, a pantyhose-style compression garment is ideal for this condition, once both extremities are decongested. To preserve the results in the leg that was treated first, compression bandages should be applied. If this is not possible, the patient should be fitted with a thigh-high compression garment (preferably a relatively inexpensive standard-size garment) while the other extremity receives treatment, and then he/she can be fitted with a pantyhose-style garment. Patient in supine position. Abbreviated trunk preparation (pretreatment): 1. Abbreviated manipulation of the lateral neck lymph nodes (observe contraindications) 2. Manipulation of the axillary lymph nodes on both sides 3. Activation and utilization of the IA anastomoses on both sides to promote lymph flow across the watersheds into the drainage areas 4. Manipulation of the inguinal lymph nodes on both sides 5. Deep abdominal techniques (modified) as outlined in the basic sequences (observe contraindications). If abdominal techniques are contraindicated, diaphragmatic breathing should be substituted. Patient on the side (or in prone position), with the more involved extremity on top: 6. Rework of the IA anastomosis (IA) on the more involved side 7. Manipulation of the lateral thigh between the lateral knee and the iliac crest, using basic techniques (“bulk flow” techniques) Patient in supine position: 8. Rework of IA anastomoses on both sides Treatment of the lower extremity: 9. Rework the inguinal lymph nodes on the more involved leg 10. Manipulation of the lateral thigh between the knee and the iliac crest. Modified effleurage as well as pump techniques, combination of pump and stationary circles, and rotary techniques should be used. This sequence should be followed up with rework techniques across the watersheds into pretreated drainage areas. 11. Manipulation of the medial aspect of the thigh toward the lateral aspect, using stationary circles. This technique should be repeated over the entire length of the thigh and followed up with rework techniques toward the drainage areas. 12. Vasa vasorum technique in the area of the femoral vein 13. Manipulation of knee, lower leg, and foot as outlined in the basic sequence techniques 14. Rework of lower extremity, including the inguinal lymph nodes If necessary, patient in prone position: 15. Manipulation of the posterior knee and lower leg as outlined in the basic sequence techniques Patient in supine position: 16. Rework of the IA anastomoses (IA) on both sides, axillary lymph nodes on both sides, inguinal lymph nodes on the less swollen leg, and abdominal techniques 17. Application of compression bandages on both, or the more involved extremity Head and neck lymphedema (HNL) is much less common than edema of the extremities, but HNL is a particularly concerning complication for patients and their families, especially when severe, as in the case shown in Fig. 5.26a, b. When HNL causes eyelid swelling, tasks involving vision, such as reading, writing, walking, and driving, may be affected. When the lips and tongue are edematous, articulation, chewing, swallowing, and even respiration can be impaired, possibly requiring a tracheotomy. Breathing can also be affected in patients who have undergone a total laryngectomy when severe submental and anterior neck edema occludes the tracheostoma, requiring the use of a device such as a laryngectomy tube or laryngectomy button to maintain a patent airway, as in Fig. 5.26b. Even when the edema is relatively minor and does not create a functional impairment, cosmetic concerns can arise that create psychosocial and emotional issues, since neck and facial edema cannot be easily hidden. HNL is often overlooked, misdiagnosed, or minimized as an inevitable and untreatable outcome of cancer treatment. At other times, a clinician may identify HNL but be ill prepared to treat the patient because of a lack of experience of the condition. The ability to effectively evaluate and treat HNL is crucial to maximizing the patient’s quality of life. The information presented in this chapter is intended to reduce clinician concerns and assist in the evaluation, treatment planning, and management of HNL. Fig. 5.26a, b Severe lingual and facial edema. a 16 days after base of tongue resection. b 11 months after total laryngectomy. HNL may be present with primary lymphedema, either in isolation or as part of a syndrome, and is a characteristic of Hennekam syndrome, Turner syndrome, Milroy disease, Apert syndrome, and other disorders.2 Primary lymphedema of the head and neck, however, is less common than primary lymphedema of the extremities and will not be addressed in this chapter. Inflammatory causes of facial lymphedema include severe rosacea (including rhinophyma and otophyma), acne vulgaris, Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome, and other dermatologic conditions.2 While the most common cause of lymphedema worldwide is filariasis,3,4 this author is unaware of any articles documenting filarial lymphedema of the head and neck. More commonly, HNL presents as a secondary lymphedema due to injury of the lymphatic tissues from chronic infections, blunt force trauma, surgery, radiotherapy, or vascular obstruction by a mass (malignant lymphedema)2 as shown in Fig. 5.27. Facial edema is a potential complication of certain cosmetic and dermatologic procedures, though chronic HNL after cosmetic procedures is not commonly reported. Manual lymph drainage (MLD) following facelift procedures has been used to reduce postoperative edema. Variations of traditional facial drainage pathways are implemented according to surgically altered tissue orientation.5 HNL is not common after surgery for noncancerous maladies of the head and neck, though with any surgery the potential exists for drainage impairment and edema due to scarring. One possible explanation for the higher incidence of HNL after the removal of malignant lesions compared with nonmalignant lesions is that the lymphatics are typically not removed in head and neck surgeries for patients not undergoing cancer treatment.6–9 HNL occurs most frequently in patients who have undergone surgery and/or radiotherapy for cancer3 and seems to be most severe when multimodality treatment is provided, though the role of chemotherapy in the development of HNL is not known. Taxane-based chemotherapy has been linked to lymphedema of the extremities,10 and HNL has been reported in patients treated with cisplatin10,11 combined with radiotherapy. There are no published accounts of HNL following chemotherapy in isolation for head and neck cancer, though pemetrexed-induced edema of the eyelid and periorbital region has been reported with lung cancer treatment.13 At this time, there are not sufficient data to suggest a causative relationship between most current chemotherapy regimens and chronic HNL. HNL has been documented in as many as 48% of patients who received radiotherapy to the head and neck.14 The insult to the lymphatic system that occurs from radiotherapy can be widespread, since the primary tumor, adjacent soft tissues, bony structures, and relevant lymphatic drainage pathways may all be irradiated in an effort to shrink existing tumors, treat persistent microscopic disease, and prevent metastasis. Tissue fibrosis is a common complication of radiotherapy and can inhibit lymphangiomotoricity and effective tissue drainage. Patients who receive radiation to the head and neck often develop chronic edema of tissues within the irradiated field, which commonly encompasses the lower face, neck, and supraclavicular fossa. When re-irradiation is required to treat cancer recurrence, further tissue damage occurs, increasing the severity of tissue fibrosis and associated HNL.15 Surgery to address head and neck cancer commonly requires the removal of the tumor and the surrounding soft tissues. Removal of bone may also be required if there is tumor invasion or if there is severe damage to the bone from radiotherapy (osteoradionecrosis).16 Depending on the extent of the surgery, reconstruction may be required with pedicled flaps such as pectoralis and rotational flaps, which retain their native venous, arterial, and lymphatic vessels. In more complex cases, free tissue transfers from one part of the body to another may be required. For example, tissue from the forearm or thigh may be used to replace a portion of the tongue or pharynx or to cover the surgical defect after removal of a portion of the face, as shown in Fig. 5.28. These “free flaps” require microvascular surgery to reattach blood vessels for flap viability. Lymphatic vessels are not commonly reconnected in these procedures, however, leaving only the venous system to drain the free flap, which can swell substantially at times. Lymphadenectomy is a common surgical procedure in the treatment of head and neck cancer, often requiring removal of more than 30 cervical, facial, mediastinal, paratracheal, or supraclavicular lymph nodes.17–19 When sacrifice of jugular veins is required due to tumor involvement or severe radiation scarring, the disruption of the venous drainage system in the head and neck increases the risk of HNL. This lymphatic and venous disruption results in a lympho-venous or “mixed edema,” which is typically less responsive to treatment than a pure lymphedema. Additionally, surgical scarring can directly impact the development of HNL due to a “trapdoor effect,”20 in which a scar prevents drainage through the lymphatic channels of the skin, resulting in edema above the scar but not below. Multimodality cancer treatment creates a unique environment for the development of both mild and severe lymphedemas in the face and neck that can be challenging to evaluate and treat. Piso et al. published a reliable assessment protocol for facial edema in 2001,21 yet HNL evaluations vary from facility to facility and often from clinician to clinician. Inconsistency in evaluation methodology hinders objective data acquisition and analysis to determine best treatment practices, forcing reliance on subjective data such as visual assessment, patient questionnaires, and clinicianscored rating scales. Development of high-tech solutions to evaluate HNL has been limited, though ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging have been reported as diagnostic tools for edema assessment in the head and neck.2,22,23 Efforts are being made, however, to implement standard evaluation protocols for HNL.24,25 Components of a basic HNL evaluation are suggested below. Clinical assessment of the patient is the most important aspect of any lymphedema evaluation, but there are specific concerns when evaluating a patient with HNL. The traditional assessment of tissue integrity, warmth, color, firmness, pitting, and tissue changes must be included. An accurate, thorough medical history is crucial, since intraoral, facial, or neck edema may result from infection, hypothyroidism, allergic reactions, postoperative seroma, hematoma, angioedema, lymphatic metastasis, or other causes.2,26 When the presentation and history do not support the diagnosis of lymphedema, referral to the patient’s physician for further evaluation is appropriate. For example, distended jugular veins in the presence of facial edema suggests superior vena cava syndrome, which is often caused by a mass compressing the superior vena cava and can constitute a medical emergency.27 A significant history of upper-quadrant deep vein thrombosis (DVT), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), transient ischemic attack (TIA), carotid artery compromise, congestive heart failure (CHF), renal disease, hyperthyroidism, tissue breakdown, or other medical concerns may be sufficient to withhold lymphedema treatment, despite the severity of the swelling.26 Lymphedema treatment may result in a CVA or increased edema if provided inappropriately and could cause death if there is tumor invasion of the carotid artery and manipulation results in rupture of the vessel (carotid blow-out). Lymphedema management may be requested as a palliative treatment to temporarily alleviate discomfort or reduce functional impairments that result from massive facial edema. Palliative treatment can improve the patient’s quality of life and should be provided if it appears that treatment can be effective and there is no immediate risk of harm, but treatment is not appropriate in all cases. If you have concerns about the patient’s safety, further discussion with the patient’s physician may be warranted, since physician approval is essential before initiating any HNL treatment. Fig. 5.30 Facial composite measurements. 1. Tragus to mental protuberance; 2. Tragus to mouth angle; 3. Mandibular angle to nasal wing; 4. Mandibular angle to internal eye corner; 5. Mandibular angle to external eye corner; 6. Mental protuberance to internal eye corner; 7. Mandibular angle to mental protuberance. (Adapted from Smith and Lewin 2010.)24 Table 5.1 Obtaining a composite neck measurement