and Karl Reinhard Aigner3

(1)

Department of Surgery, The University of Sydney, Mosman, NSW, Australia

(2)

The Royal Prince Alfred and Sydney Hospitals, Mosman, NSW, Australia

(3)

Department of Surgical Oncology, Medias Clinic Surgical Oncology, Burghausen, Germany

In this chapter, you will learn about:

Can cancer be cured? An outline of prognostic factors

Methods of Treatment

Surgery

Radiotherapy including brachytherapy

Chemotherapy – anti-cancer drug

Hormone therapy

Immunotherapy

Cell-mediated anti-cancer activity

Other treatments under study

General care

Supportive care and supportive care teams

Psychological and spiritual help

Follow-up care

The specialty of palliative care

“Alternative medicine”

8.1 Can Cancer Be Cured? An Outline of Prognosis

Although cancer is a frightening word, it is a fact that in modern developed societies, most cancers are cured. The possibility of cure of a cancer depends upon a number of factors, especially the tissue from which it has grown and the type of cancer cells in it, the size and position of the tumour in the body, the degree of abnormality of the individual cancer cells, the structures into which the cancer may have grown and the presence and site of any metastatic spread. The age and general health of the patient are also significant. The patient’s natural defence reactions may be highly significant although, as yet, not clearly understood and not yet able to be measured with any confidence.

Many of the most significant factors will depend upon how quickly the cancer is detected and treated. A small cancer detected early and before it has spread or involved other tissues may be eminently curable, whereas the same cancer neglected, perhaps for some months, until it has enlarged and spread to other sites may be quite incurable.

Many years ago, a great American pathologist, Arthur Purdy Stout, said:

The best chance of curing cancer lies in the hands of the therapist who makes the first attempt.

Nowadays, this should be paraphrased as:

The best chance of curing many advanced and aggressive cancers lies in the hands of the team of therapists that makes the first attempt.

That is, a cancer that has recurred after a failed attempt at treatment is more difficult to cure than it would have been at the first attempt. The quality of treatment given to the patient, especially in the initial treatment, is a most important factor in determining whether or not a cure is likely. For difficult cancers, this is often now best achieved with integrated treatment and a team approach.

8.2 In Western Societies More Cancers Are Cured than Not Cured

This is certainly true because the most common cancers are basal cell cancers of the skin and squamous cell cancers of the skin. Not only do these cancers grow relatively slowly and spread relatively late, if at all, they are usually obvious to the patient and doctor when they are quite small, and if properly treated at that stage, they are eminently curable. Even the more aggressive and dangerous pigmented skin cancer, the melanoma, is usually eminently curable in its early stages. With people becoming more aware of the danger of any change in a pigmented mole, or other dark spot on the skin, most melanomas are now detected before they have spread. If properly treated at this stage, they are effectively cured.

All this is good news but, even better, is the fact that even excluding skin cancers, more cancers can now be cured than not cured.

The common cancers of the breast and bowel and cancers of the uterus are usually curable now that methods of early detection are widely practised. It is most important that these cancers should be detected early as the outlook is so much better if treatment is initiated when these cancers are small. For this reason, a great deal of effort has been spent in establishing cancer screening clinics to detect potentially curable cancers before they reach an incurable stage. This is now likely to need a diagnostic and therapeutic team effort.

Cure can now be expected for most cancers in the head and neck region, including the lips, mouth and throat, larynx, salivary glands and thyroid gland.

Until fairly recently, cancers that develop in cells scattered widely throughout the body tissues, such as the lymphomas and leukaemias, were considered incurable, but with modern treatment methods, increasing numbers of patients with these malignancies are being cured including the majority of children who develop leukaemias.

The most common internal cancer in men, prostate cancer, can now usually be diagnosed at a curable stage. However, because most of these cancers are slowly growing and not necessarily life-threatening during the patient’s otherwise expected lifespan, there may be uncertainty as to whether radical treatment to establish a cure is justified. Sometimes the outlook without curative treatment does not justify the severe side effects of curative treatment, especially in elderly men with other health problems.

The outlook for germ-cell cancers of the testis underwent dramatic change over the last two to three decades of the twentieth century. From being cancers with a poor prognosis except when treated at a very early stage, most are now cured when treated with combined and integrated therapy programmes using modern chemotherapy, radiation therapy and surgery.

Integrated treatment methods have also improved the curability of a number of other cancers including more advanced head and neck cancers; sarcomas, especially in limbs; and previously high-risk stomach and breast cancers.

Cancers with the worst prognosis (least likely to be cured) are often those that develop in deep body tissues and are usually not obvious until they have spread to lymph nodes or other tissues. These include cancers of the oesophagus, pancreas and lung. Hence, the search for methods of earlier detection of these cancers. Other cancers with poor prognosis include those in organs that cannot be easily dispensed with such as the liver or a major part of the brain.

With modern endoscopic techniques, stomach cancer can now also be detected at a curable stage. In Japan, where this cancer is common and screening tests are becoming a routine, most are now diagnosed at an early stage and are cured.

8.3 Methods of Treatment

The three mainstays of cancer treatment are surgery (meaning operative surgery), radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

8.3.1 Principles of Treatment of Potentially Curable Regional Cancers

The main principle of treatment of any new and potentially curable cancer is to treat one step beyond the apparent limits of the cancer.

With an inflammatory condition, such as an acutely inflamed appendix, only the appendix needs to be removed to cure the condition. Similarly in treatment of benign lesions such as benign cysts, adenomas or polyps, only the lesion needs to be removed. Best treatment of cancer, however, requires surgical removal of more than just the apparent cancer. Tissues adjacent to the cancer into which cancer cells might have spread are also removed. Similarly if treatment involves radiotherapy, it is given to tissues beyond the apparent edge of the cancer, that is, tissues into which microscopic cancer cells might have spread. Chemotherapy is often given in addition to surgery and/or radiotherapy if the cancer being treated is one that has significant risk of having already spread beyond the local primary site or region being treated even though there may be no evidence of more distant spread.

The main principle of treatment of any new and potentially curable cancer is to treat one step beyond the apparent limits of the cancer.

8.3.2 Surgery

The discipline of surgery is that part of medicine and medical practice that is likely to involve the need of a surgical operation. The word surgery is also often used to mean operative surgery, and it is in this context that the word surgery is used in the following paragraphs.

Before the discovery of general anaesthesia and the first use of ether as a general anaesthetic by Dr Crawford Long in America in 1842, operative surgery was very primitive, but nevertheless it was the only available effective cancer treatment.

Early use of general anaesthesia for operative surgery was followed by rampant cross infection with a high mortality rate. The situation changed after the discovery of microorganisms in infected wounds by great world scientists Pasteur in France, Koch in Germany, Semmeilweiss in Hungary and Lister in England (Fig. 8.1).

Fig. 8.1

(a) Operative surgery before 1842. (b) Lister using Lysol spray to help create asepsis in an operating theatre

These changes in operating under general anaesthesia with aseptic conditions allowed operative surgery to develop and progress to what it is today. Thus, operative surgery became the first widely used effective and generally applicable anti-cancer treatment.

Surgery was thus the first effective form of cancer treatment. It is now used to establish a diagnosis, to effect a cure or, in some advanced or incurable cases, to give good palliation and relief of symptoms. When possible, the surgeon’s primary objective is to excise the cancer in its entirety, together with all adjacent tissues into which cancer cells may have spread. For many cancers, especially for early skin cancers and small cancers on lips or in the mouth, surgery offers a relatively simple, straightforward, quick and effective method of eradicating cancers. A complete cure can be expected without any residual problem. For more advanced cancers that have spread to or are likely to have spread into draining lymph nodes, the surgeon removes not only the primary cancer but all the draining lymph nodes likely to be involved. The primary cancer and lymph nodes are best removed in continuity in one block of tissue where this is feasible. This is called a “block dissection” and a high incidence of long-term cure can also be expected. If a great deal of tissue has to be removed, the surgical team may need to do some form of plastic or reconstructive surgical procedure to leave as little defect or deformity as possible. The surgical removal of a tumour is also the most effective cure for the cancer associated weight loss (cancer cachexia), as the cellular source of the abnormal metabolism driving the weight loss is removed.

Used alone successful surgery depends upon establishing diagnosis and treatment early in the disease and before the cancer has spread into tissues that cannot be resected with the primary cancer.

For breast cancer that is confined to the breast with possible early involvement of lymph nodes in the axilla, the most common surgical treatment over the past 100 years has been total removal of the affected breast and lymph nodes from the axilla as one block of tissue. This operation, called a radical mastectomy, has cured many women with breast cancer over the years, but nowadays, less radical operations have been equally successful.

For deep-seated cancers, the whole or part of the involved organ is usually excised together with nearby draining lymph nodes. Such has been the standard treatment for cancer of the stomach, colon, rectum, uterus, ovary, oesophagus, lung and sometimes the pancreas. For some, the cure rate by surgery alone has been good, but for others, the cure rates by surgery alone have been dismal.

Sarcomas in limbs tend to recur locally in the limb unless widely excised, and sometimes the best chance of cure by surgery, especially for big sarcomas, has been by amputation of the affected limb. Newer techniques of combined treatment (discussed later in this chapter) have reduced the need for amputation in many cases.

Exercise

What are the possible objectives of surgical operations in the treatment of cancer?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8.3.3 Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is the second oldest effective form of treatment for cancer but has been clinically available only since about the year 1900 following the work of the Curies in France and Dr Roentgen in Germany. Treatment depends upon the sensitivity of dividing cells being destroyed by X-rays or gamma rays emitted from a radioactive source. Treatment, equipment and computer-assisted techniques are constantly being improved with improved results in eradicating cancer cells and causing minimal damage to surrounding tissues and cells (Fig. 8.2).

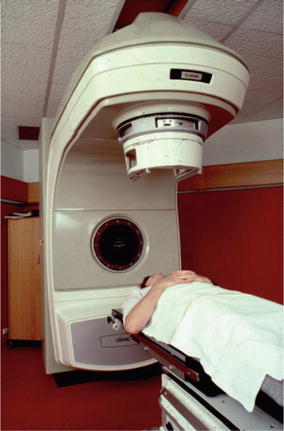

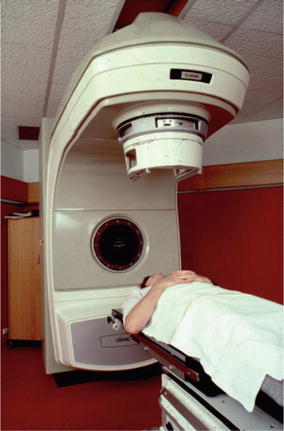

Fig. 8.2

Photograph of a patient ready for treatment with supervoltage external radiotherapy

Radiotherapy has the advantage of avoiding a surgical operation, but in many cases, treatment over 5–8 weeks is required. Radiotherapy has the disadvantage of causing some damage to normal tissues and cells covering and surrounding the cancer in the area treated (the irradiation field). The radiotherapist must have the patient in a correct position so that the radiation beams will include the whole tumour in the irradiated field with minimal exposure of normal tissue. This will allow greatest destruction of tumour cells with as little as possible damage to surrounding normal tissues and cells.

Radiotherapy alone is effective treatment for many skin cancers, for some head and neck cancers and for some deep-seated cancers that cannot be totally removed by surgery. It is also used as a palliative treatment to give relief by reducing the size of some cancers that cannot be cured by surgery or other means.

The dose of radiotherapy used is critical and must be given by experts. Too little will not destroy cancer cells, but too much will destroy normal tissues and may result in loss of tissue sometimes with painful ulceration of overlying skin which may not heal and other long-term local problems such as damage to an underlying lung or other tissue. The dose is also cumulative, that is, once radiotherapy has been given to a part of the body in a therapeutic dose, it cannot ever be given again to the same site without risk of serious tissue damage.

Radiotherapy is now often used in combined, integrated treatment programmes, especially with surgery and/or chemotherapy.

The actual administration of radiotherapy is quite painless although it may leave some skin changes, like an erythema resembling sunburn, and may make the patient feel listless and tired, adding to his or her feeling of depression. Depression is a natural feature of having a cancer. Radiotherapy sometimes adds to the depression, but it usually improves when active treatment has been completed. Although the red flush of skin change settles a few weeks after radiotherapy, some minor skin changes with small, visible blood vessels called telangiectasia are often a permanent feature of an area that has in the past been irradiated.

8.3.3.1 Brachytherapy

Brachytherapy is a form of radiotherapy in which radioactive needles or “seeds” are inserted into a tumour to give a measured dose of irradiation directly to the cancer. The dose of irradiation given by such needles (withdrawn after the required dose has been administered) or “seeds” (left permanently in place in the cancer) is critical. It is also critical to place the radioactive material in such a position that all of the cancer tissue receives a satisfactory dose of irradiation. Traditional external irradiation can more reliably cover the needed irradiation field but will irradiate surrounding tissues. Brachytherapy will more specifically deliver a dose of irradiation into the cancer but has a greater risk of missing some of the outlying cancer cells. In some clinics, combined use of these two forms of radiotherapy can be used in treating some cancers. In some clinics, brachytherapy or combined external irradiation with brachytherapy is becomingly increasingly used in treating prostate cancer when there is a localised limited cancer focus. Results are now believed to be equivalent to radical surgery but with the advantage of fewer side effects.

Radiotherapy is now often used in combined, integrated treatment programmes, especially with surgery and/or chemotherapy. For many advanced and aggressive cancers, combined and integrated treatment will affect cures that would have been unlikely by using one treatment modality alone. This is why it is becoming increasingly important for patients with aggressive or advanced cancers to be seen by clinicians working in cooperative multidisciplinary teams.

Exercise

What are the advantages and disadvantages of treating a cancer by brachytherapy as opposed to external radiotherapy?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8.3.4 Chemotherapy (Cytotoxic Drug Treatment)

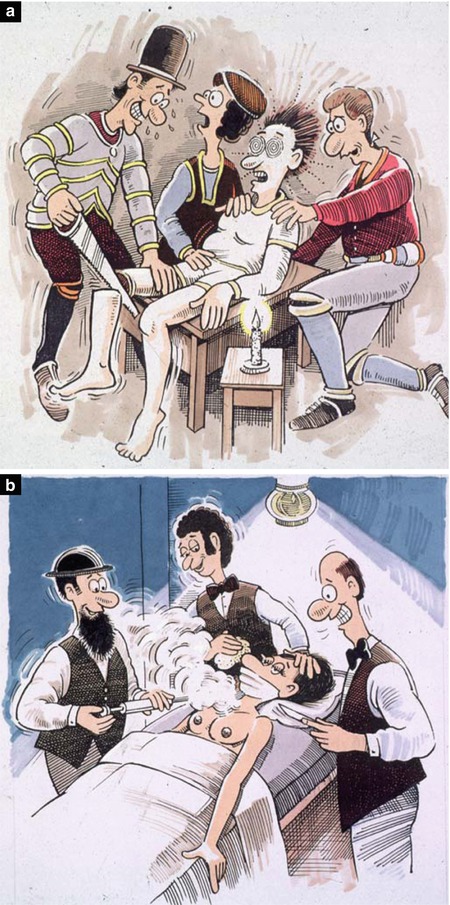

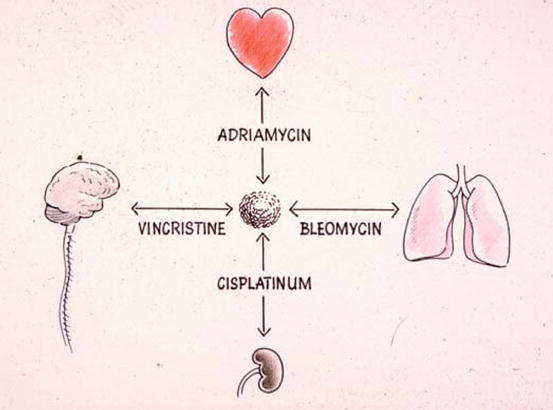

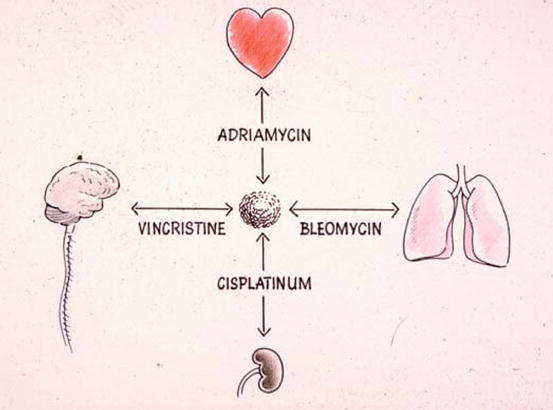

Doctors, scientists and others have been searching over the centuries for chemical substances that might cure cancer. The first effective such treatment was reported by Dr George Beatson from the Glasgow Royal Cancer Hospital early in the twentieth century. Dr Beatson reported that oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries) depressed growth of some breast cancers. Hormonal management of breast cancer followed that observation. Next was a report in 1941 by two American doctors, Charles Huggins and Clarence Hodges, that some prostate cancers responded to treatment with the female hormone stilboestrol. 4 years later in 1945, it was first observed that a gas that had been used during World War I destroyed dividing cells, and so nitrogen mustard wa s discovered as being a drug that could be used clinically against cancer cells in patients. This was the beginning of modern anti-cancer chemotherapy. Since that time, a large number of effective anti-cancer drugs have been developed. These drugs have their greatest effect on dividing cells, and because cancer cells are more constantly dividing than normal cells, they are more likely to be affected than normal body cells. The present anti-cancer drugs are grouped or classified according to how they affect dividing cells (Fig. 8.3).

Fig. 8.3

Diagram illustrating the sites of greatest activity on dividing cells of some of the anti-cancer agents

Exercise

Why are cancer cells more likely to be affected by chemotherapy than normal cells?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8.3.4.1 Anti-cancer Drugs

Just as details of surgical procedures must be left to trained surgeons and the details of the best use of radiotherapeutic procedures must be left to specialist radiotherapists, so too details of best use of anti-cancer agents are highly complex. The use of complex anti-cancer agents is best guided by experts who are appropriately trained and experienced in their use. However, some knowledge of the agents most commonly used should be helpful as a basis for further understanding.

The number of anti-cancer drugs is constantly increasing as newer agents with more selective actions against particular tumour types are discovered. In general, they are grouped as:

Antimetabolites. This group of anti-cancer agents predominantly interfere most with synthesis and metabolism of DNA and, to some extent, RNA. They include methotrexate, 5-FU (5-fluorouracil), cytarabine, gemcitabine and 6MP (6 mercaptopurine).

DNA–damaging agents. These include alkylating agents like cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide and melphalan; antibiotics like adriamycin, mitomycin, actinomycin D and bleomycin; nitrosoureas (such as BCNU and CCNU); and platinum derivatives like cisplatin and carboplatin.

Mitosis inhibitors. This group includes vinca alkaloids (like vincristine and vinblastine) and taxanes (Taxol).

Cancer cell enzyme inactivators. This is a new class of anti-cancer agent recently discovered and undergoing much research. The first, code-named STI 571 (trade name Gleevec or Glivec), is the enzyme tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Tyrosine kinase is an essential for cancer cell reproduction. STI 571 was first found to counteract the Philadelphia chromosome of chronic myeloid leukaemia, and in treating this leukaemia, results have been very encouraging. STI 571 is now being used in trials of treating other cancers, particularly with certain gastrointestinal stromal cancers and renal cancers, with encouraging results. There may be a place for similar management of some breast cancers and prostate cancers.

All effective anti–cancer drugs presently available have side effects.

Unfortunately all effective anti-cancer drugs presently available have side effects that affect some people more than others. Some become manifested early as acute toxic side effects. Some are long-term or late side effects and may not be apparent for months or even years. Until all adverse side effects of such agents are well understood, experienced specialists should oversee their clinical use.

8.3.4.2 Using Combined Anti-cancer Agents

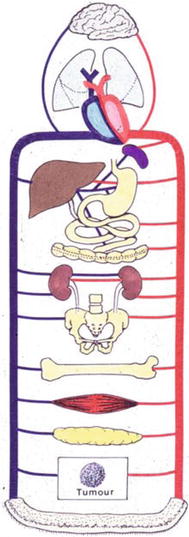

In treating cancers, the specialist cancer clinician (oncologist) selects drugs that are known to be effective against the type of cancer being treated with least possible damage to normal body cells. In general, appropriate combinations of effective drugs are more effective than large and increasingly toxic doses of one drug only. Much research is constantly being carried out to discover the most effective and safest combinations and dose and timing schedules of drugs against different types of cancer with minimal damage to normal dividing cells (Fig. 8.4).

Fig. 8.4

Diagram indicating the principle of use of multiple agents in combination in treating a cancer rather than using larger and more toxic doses of just one agent. As illustrated, provided the drugs are known to be active against the type of cancer being treated, a selection of two or more agents should have increased activity against the target cancer cell. It is like hitting the cancer cell in two or more places at the same time. It is safer to avoid using drugs with the same side effects so that normal cells are less likely to be damaged by multiple agents

8.3.4.3 Time and Concentration of Anti-cancer Cytotoxic Drugs on Different Cancer Cell Types

There is also much to be learned about when anti–cancer cytotoxic drugs are best integrated with radiotherapy or surgery.

Another aspect of the use of anti-cancer drugs is the sensitivity of the cancer cells being treated in relation to the length of time of their exposure to the drugs and their relative sensitivity to drug concentration. For example, 5-FU is generally more effective if given by continuous infusion over several days, whereas melphalan seems to have a greater impact given in greater concentration over a shorter period, possibly an hour or so. Similarly, cancers of different types respond differently to different periods of exposure and to different concentrations of agents. Gastrointestinal cancers and mouth and throat cancers seem to respond best to continuous prolonged drug exposure over days or weeks, whereas melanoma responds best to a more intense concentration of agents that can only be given over a short period. There is still much to be learned about dose, combinations, length of time of exposure and concentration of agents to achieve greatest effect on the type of cancer being treated with minimal side effects. There is also much to be learned about when anti-cancer cytotoxic drugs are best integrated with radiotherapy or surgery.

8.3.4.4 Palliative Chemotherapy

The most widely applied use of the anti-cancer drugs is in treating widespread cancers or cancers that for one reason or another cannot be treated effectively by surgery or by radiotherapy. Although some drugs will, on occasions, cure some widespread cancers, in general, this form of treatment is palliative. Palliation means that the cancer may be reduced in size and the patient may be given relief of symptoms for some time, but almost invariably the cancer will redevelop sooner or later, at which time it will be more resistant to anti-cancer agents. Eventual death from the cancer is likely.

Palliative chemotherapy, by reducing the cancer, will usually prolong life and should make the patient more comfortable. Sometimes, however, because of the inconvenience and problems associated with treatment and the possible distress of side effects (see “side effects”), there is doubt as to whether palliative chemotherapy is worthwhile. In each case, the medical attendants should discuss the likely benefits and possible problems with the patient and members of the patient’s family before a final decision is made about having this form of treatment. Although it is the doctor’s responsibility to give informed advice, the final decision as to whether to have palliative chemotherapy should be made by the patient. If doubt exists in the patient’s mind about the desirability of having such treatment, a trial course of treatment may be appropriate, that is, that treatment be commenced with the proviso that if the patient finds treatment too distressing, treatment can be modified or stopped at any time.

8.3.4.5 Adjuvant Chemotherapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy is chemotherapy given following surgery or radiotherapy and is used to treat cancers where it is known there is a significant risk that scattered cancer cells may be present somewhere even though they cannot be detected.

The most proven value of adjuvant chemotherapy is in treating women who have had a breast cancer treated by surgery (mastectomy, segmentectomy or lumpectomy) or a combination of surgery and radiotherapy to the breast region. These are patients who have certain prognostic factors that suggest that although undetectable, there is a significant risk of some cancer cells already having spread beyond the treated region. Adjuvant chemotherapy is also given as part of the treatment for people (usually young people) who have had bone cancer (osteosarcoma) treated by surgery. The surgery may have been amputation of a limb. Post-operative chemotherapy is now standard even with small osteosarcomas because there is a high risk that some cancer cells will have already escaped from the local tissues and formed micro-metastases in the lungs. Treatment of ovarian cancers and some colorectal cancers also now often includes administration of adjuvant chemotherapy to get best long-term results.

8.3.4.6 Systemic and Regional (Intra-arterial) Chemotherapy

(a)

Systemic chemotherapy

The most convenient and simplest way of giving a measured dose of chemotherapy is by intravenous delivery, either by bolus injection or by slow infusion into a vein. After intravenous delivery, drugs are distributed by the bloodstream more or less equally to all parts of the body and should affect cancer cells wherever they may be.

Whilst surgery is limited to treating cancers localised in a particular region that can be excised and radiotherapy is limited to treating cancer cells in a limited radiation field, chemotherapy is generally given systemically, that is, to treat the body as a whole. Some anti-cancer drugs can be given by mouth but most are given by intravenous injection or infusion. This method of chemotherapy is likely to be the most effective as adjuvant therapy when there is a significant risk that there may be widespread cancer cells remaining somewhere after a primary cancer has been eradicated.

It is sometimes possible to concentrate anti–cancer drugs to the cancer by injecting or infusing the drugs directly into the artery supplying blood to the cancer.

(b)

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

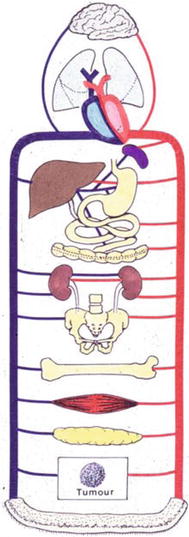

Regional (intra-arterial) chemotherapy Fig. 8.5

Fig. 8.5

Diagram illustrating the principle of intra-arterial chemotherapy. If all active anti-cancer agents are infused into a small artery that supplies the cancer with all its blood (illustrated in the bottom of the diagram), the cancer will be exposed to a greater initial concentration than if the agents are infused into the venous circulation. Infused into the venous circulation, they will be distributed more or less equally but in lower concentration to all body tissues. The value of this technique depends on the agents used being active in the form in which they are given. Some agents, e.g. cyclophosphamide, need to be activated by passage through the liver so that for them intra-arterial infusion has no advantage. For some other agents, exposure over a prolonged period of time may be of greater importance than a more concentrated exposure

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree