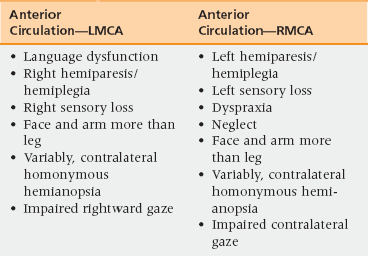

40 Upon successful completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Use appropriate stroke terminology. • Identify appropriate classification of strokes as a guide to selection of secondary stroke prevention measures. • Define transient ischemic attack (TIA) in physiologic terms and discuss its appropriate management. • Identify individualized risk factors for stroke and outline appropriate management of these factors. • Describe a step-wise approach to hospitalized stroke care that maximizes recovery, minimizes complications, and uses principles of accountable care and transitions of care. Every year, AHA/ASA publishes epidemiologic updates revealing a progressive increase in stroke incidence. As of 2012, 795,000 people had experienced a new or recurrent stroke per year and approximately 76% of these are first attacks. This increase is most likely related to more aggressive evaluation and better imaging technology. Of the types of strokes, 87% are ischemic, 10% intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), and 3% subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).1 Hospital admissions for ICH have increased by 18% in the past 10 years. This is attributable to increases in the number of elderly people (many of whom lack adequate blood pressure control) as well as to the increasing use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapies. Mexican Americans, Latin Americans, African Americans, Native Americans, Japanese, and Chinese continue to have higher incidences of ICH than do white Americans.1 Rudolf Virchow, Amédée Dechambre, and Miller Fisher are some of the contributors to the current understanding of the mechanisms of ischemic stroke: description of thrombosis, (Virchow’s triad), characterization of lacunar infarction, and understanding of carotid occlusion and embolism, respectively. Their work led to the etiopathogenic classification of cerebrovascular diseases as landmarked by the World Health Organization in the 1980s and by the AHA/ASA Scientific Committee in 2010. Location of blood in hemorrhagic strokes determines the subclassification of either intracerebral, ICH (blood within the parenchyma), or subarachnoid (SAH, blood in the subarachnoid space).2–4 Cerebral embolism results from the obstruction of a cerebral vessel by particles moving upstream, most typically originating from a cardiac source. Approximately 20% of strokes are embolic. Of these, 80% will affect the anterior circulation and 20% the vertebrobasilar system. Debris can be made of platelet aggregates, thrombus, cholesterol, calcium, bacterial, neoplastic cells, or mixomatous material. Different conditions can be classified as medium to high risk for cardiac embolism.4 The aortic arch can also be a source of debris particularly plaque and plaque-thrombus embolus. A transesophogeal echocardiogram (TEE) assists in the identification of aortic arch pathology as a potential cause of stroke. Paradoxical embolus refers to the origin of particle being venous rather than arterial. Emboli detour into the arterial system by means of a shunting mechanism, most typically through a patent foramen ovale (PFO), or pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. In such cases, characteristics of the embolus could be very diverse: air, fat, amniotic fluid.4 Approximately 5% of strokes are the result of other causes such as arteritis, vascular dissections, sickle cell anemia, cerebral venous thrombosis, vasospasm, and genetic vasculopathies. When the cause of a stroke is not identified, strokes are referred to as cryptogenic. Cryptogenic classifications may be given when the evaluation was considered incomplete, there is more than one cause of stroke identified, or the cause remains in question after complete evaluation.2–4 The etiopathogenesis of hemorrhagic stroke, ICH, and SAH are listed in Box 40-1. The most common cause of ICH is hypertension; the most common cause of SAH is aneurysmal rupture.4 • Sudden weakness of arm, leg, and/or face, usually on one side of the body • Sudden sensory loss, usually on one side of the body • Sudden dizziness or loss of balance Limb-shaking transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) may precede an anterior cerebral artery (ACA) occlusion and are caused by intermittent compromised flow through a critically narrowed vessel. Compromised flow to the vertebrobasilar system can result in drop attacks. Transient retinal ischemia caused by compromised flow to the ophthalmic artery results in amaurosis fugax, a transient loss of vision in one eye. Dizziness in a patient older than age 60 should raise the concern for vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Examination findings such as unidirectional nystagmus, test of skew (vertical strabismus), and head impulse testing can help discern peripheral from central causes of vertigo.5 Stroke mimics are common sources of diagnostic errors, suboptimal treatments, and readmissions. Tumors, metabolic disorders, and in particular, rapid changes in glucose values, hemiplegic migraine, infection, seizures/Todd’s paralysis, and conversion disorders are among the most common alternative diagnoses. Seizures should be considered if the patient has an altered level of consciousness, involuntary movements, and positive symptoms such as tingling. Consider musculoskeletal disorders in the presence of pain. Identification of the vascular territory responsible for the stroke is important in guiding decisions for treatment strategies and for counseling patients/families regarding therapeutic options, risks and expectations for complications, morbidity, and mortality. Distinction must be made regarding the vascular territory involved: large vessel versus small vessel injury, cortical versus subcortical, and anterior versus posterior circulation (Table 40-1, Boxes 40-2 to 40-5).

Transient ischemic attacks and stroke

Prevalence and impact

Pathophysiology

Differential diagnosis and assessment

Oncohema Key

Fastest Oncology & Hematology Insight Engine