Surgery, either alone or in combination with other therapeutic options (chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy), remains an essential component of a multimodality approach to midstage esophageal cancer and an effective means to achieve a long-term disease-free state. However, despite considerable improvements in reducing the perioperative morbidity and mortality of esophageal resection, surgery alone—regardless of the approach—is inadequate to achieve a cure in the vast majority of patients.1,2 The history of surgical resection for esophageal carcinoma has been well described by Hurt.3 The first successful resection of a cervical esophageal carcinoma was performed by Czerny in 1877. Denk followed by describing the first “pull through” operation in a cadaver that removed the esophagus without a thoracotomy in 1913. Turner further developed the technique and performed the first successful Denk-type operation on a patient in 1933. However, due to early failures, the transpleural esophageal resection became the established procedure for esophageal carcinoma until Orringer reintroduced the transhiatal Denk-Turner “pull through” operation in 1976 reporting impressive initial results—subsequently updated and validated—that mimicked those produced with the transthoracic approach.4,5

Proponents of the transhiatal esophagectomy, transthoracic (Ivor Lewis) esophagectomy, three-field lymphadenectomy, and minimally invasive esophagectomy have described the advantages of their respective techniques despite the lack of solid evidence demonstrating a disease-free or overall survival benefit of one technique over another.6–10 The proposed advantages of the transhiatal esophagectomy include less pulmonary complications with the avoidance of a thoracotomy, and the relatively benign nature of cervical esophagogastric anastomotic leaks leading to reduced perioperative mortality.8,11 Initial critics of this approach were concerned about inadequate hemostasis and a compromised lymph node dissection when utilizing a “blind” mediastinal mobilization. These concerns have been allayed and the equivalent oncologic efficacy of the transhiatal approach has been consistently confirmed in recent population-based studies, meta-analyses, and one large prospective randomized phase III trial.9,12,13 More important than the operative approach are the surgeon’s case volume, ability to individualize the procedure based on the patient’s performance status, tumor location and extent, and ability to rescue patients from life-threatening complications more effectively.14 The only contraindications to a transhiatal approach are the unusual occurrences of documented tracheobronchial invasion of an upper or middle third esophageal carcinoma or severe adherence of the esophagus to vital structures (secondary to a locally advanced tumor or from prior surgery) that is encountered during mediastinal exploration, which may preclude a safe dissection and therefore require additional exposure via a thoracotomy.

The impact and role of surgery in the setting of multimodality therapy with either neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy continue to be examined in ongoing clinical trials that attempt to improve on the historically dismal outcomes in esophageal carcinoma. With strong evidence for both improved median survival and R0 resection rates after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy without increasing the risk of perioperative outcomes, exercising the proper surgical technique to optimize the oncologic outcome is essential.15

All patients who are deemed fit to undergo esophagectomy benefit from a comprehensive preoperative program designed to educate them on the importance of pulmonary exercise, smoking cessation, and nutrition to diminish the risk of postoperative adverse events. Patients with dysphagia who are undergoing induction therapy may benefit from enteral supplementation; however, parenteral nutrition is rarely required. In the author’s practice, all patients undergo mechanical bowel preparation regardless of whether the conduit is the stomach or the colon. A staging laparoscopy with frozen-section analysis of suspicious nodules is performed on all patients at the time of resection to prevent the morbidity associated with a laparotomy for metastatic disease. The need for enteral support is uncommon after esophagectomy; however, an enteral feeding tube is placed in all patients undergoing esophagectomy in the event they are unable to maintain adequate oral intake in the immediate postoperative period. Adequate postoperative analgesia is essential and may be best managed with a thoracic epidural catheter that allows for a more effective cough, vigorous physiotherapy, and mobilization early in the postoperative period, although many of the benefits are more evident after a transthoracic approach.16

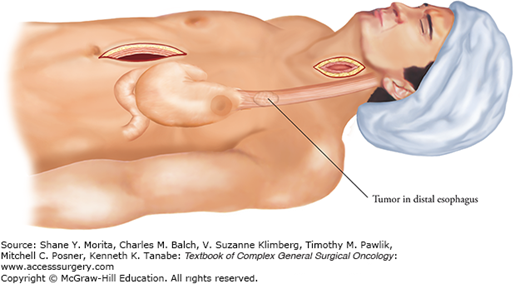

The transhiatal esophagectomy involves four phases: abdominal, cervical, mediastinal, and anastomosis. With the patient supine, the left arm is tucked leaving the right arm out at 90 degrees for venous and arterial access. Though not mandatory, a central venous catheter, if required, is placed in the right internal jugular vein. All bony prominences are padded, and the head is extended, turned to the right, and supported on a soft O-ring. The skin is prepped from the left ear to the pubis and laterally to both midaxillary lines.

The abdominal phase is initiated through an upper midline incision from the xiphoid process to the umbilicus (Fig. 87-1). The right and left costal margins are retracted cephalad toward the ipsilateral shoulders with a self-retaining table-fixed retractor. The ligamentum teres, falciform, and triangular ligaments of the liver are divided, facilitating retraction of the left lateral segment upward and to the right. The stomach is then assessed for its suitability as a conduit. The greater omentum is divided along the greater curvature of the stomach maintaining a safe distance inferior to the right gastroepiploic vessels to avoid injury to the primary blood supply to the conduit. The left gastroepiploic and short gastric vessels are identified and are ligated just outside the border of the greater curvature. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary traction on the stomach.

The gastrohepatic omentum is divided along the liver edge in the avascular plane overlying the caudate lobe. A replaced left hepatic artery arising from the left gastric artery should be preserved when encountered in this area. Careful dissection inferiorly along the lesser curvature is performed to the right gastric vessels, which in almost all instances can be preserved and provides added blood supply to the gastric tube. The remnant gastrocolic omentum is freed from the greater curvature of the stomach with attention to preserving the right gastroepiploic vessels up to its origin at the gastroduodenal artery. A Kocher maneuver exposes the border of the superior mesenteric vessels. The hepatic flexure is taken down to allow full mobilization of the pylorus to the esophageal hiatus. A pyloromyotomy (or pyloroplasty) is routinely performed to limit gastric stasis as a consequence of vagal disruption.

Prior to division of the left gastric vessels, a common hepatic, celiac-axis, proximal splenic, and left gastric lymphadenectomy is performed with all nodal tissue swept up with the specimen (Fig. 87-2). With the stomach retracted anteriorly and superiorly, the left gastric artery and the coronary vein are ligated at their origins. All remaining posterior gastric vessels are divided and all nodal tissue around the crus of the diaphragm and the aorta is dissected. Once this is completed, the peritoneum overlying the esophageal hiatus is incised and the gastroesophageal junction is encircled with an umbilical tape, which is secured and used for traction during the mediastinal mobilization. The esophageal hiatus should be widened by dividing the crus with electrocautery after ligating the inferior phrenic vein. This creates excellent exposure of the inferior mediastinum that extends superiorly to the carina. The initial dissection of the distal esophagus is performed from pleura to pleura laterally and from pericardium to aorta in the anterior/posterior plane using alternating traction and counter traction, electrocautery, and liberal use of large hemoclips to incorporate the periesophageal soft tissue. Continual assessment of whether the esophagus is fixed to the adjacent spine, prevertebral fascia, aorta, pleura, or pericardium is carried out during the dissection until the carina is reached. If the pleura are traversed, a chest tube is inserted. Hemostasis is easily achieved with surgical packing when neccesary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree