Mechanisms of TRALI

Two pathophysiologic mechanisms of TRALI have been recognized, immune-mediated TRALI and non-antibody mediated TRALI. Anywhere from 65 to 90 % of reported cases are found to be immune-mediated TRALI, which occurs when leuko-agglutinating antibodies from the donor blood bind to conjugate recipient antigens [8]. By definition, evidence of antibodies from the blood donor are present; most commonly anti-HLA and anti-HNA antibodies, with anti-HNA3a associated with worse clinical outcomes [9, 10]. The second mechanism for development of TRALI is classified as non-antibody mediated TRALI and stems from an antibody independent mechanism. Approximately 15 % of TRALI falls into this category, in which no antibodies are found in the donor blood product. Silliman and colleagues have described the non-antibody mediated mechanism as a two-hit model. The first hit involves neutrophil priming and sequestration secondary to a preexisting condition in the recipient. In the second hit, biologic modifiers such as lipids in the blood product activate neutrophils and lead to capillary leak in the lung endothelium [11, 12] (see Chap. 10).

Risk Factors

Risk factors for the development of TRALI can be broken into two categories, recipient and donor related risks. The recipient of the blood product may have underlying disease states and clinical conditions, which put them at increased risk (Table 11.2). Also the donor profile and blood components being transfused may also put the recipient at higher risk for development of TRALI.

Table 11.2

Recipient related risk factors for development of TRALI

Recipient related risk factors |

|---|

Sepsis |

Shock |

Positive fluid balance |

Liver disease/history of liver transplant |

Chronic alcohol use |

Active tobacco use |

Mechanical ventilation/increased peak airway pressures |

Increased IL-8 serum levels |

Major surgery (i.e., cardiac, orthopedic surgery) |

Hematologic malignancy |

Massive transfusion |

High APACHE II scores |

Recipient Risk Factors

Multiple recipient related risk factors are noted in the literature. Most of these studies are retrospective and small. However, it is evident from clinical data that the critically ill population is at the highest risk for the development of TRALI [13]. In one multicenter, prospective trial, history of liver transplant, chronic alcohol use, active tobacco use, shock, increased IL-8 levels in serum, increased peak airway pressures of >30 cm H2O on the ventilator, and an overall positive fluid balance were all significant risk factors for TRALI [14]. Multiple studies reveal sepsis and shock as major risk factors. Not only being critically ill, but also being on mechanical ventilation at the time of transfusion may increase risk independently. A prospective cohort study showed 33 % of patients on mechanical ventilation at the time of transfusion developed acute lung injury [15]. Multiple other studies have also shown recipient risk factors such as: major surgery within 72 h of blood transfusion, hematologic malignancy, higher APACHE II scores, and active liver disease [16]. The risk for development of TRALI also increases with the number of transfusions, as seen commonly in the trauma population where patients are receiving massive transfusions [13]. Not only critically ill patients, but cardiac and orthopedic surgery patients are also at higher risk for TRALI development [17]. The time on cardiac bypass appears to be correlated as well, with longer bypass times leading to higher risk of TRALI development [18]. Despite the multitude of recipient risk factors reported, most of which are seen in the critically ill population, TRALI is also reported in otherwise healthy individuals at the time of transfusion [19]. The development of TRALI in this healthy patient population supports the realization that the risk of TRALI is not dependent on the recipient alone.

Donor and Blood Component Risk Factors

All forms of blood products have been reported to cause TRALI, including: whole blood, packed red blood cells, apheresis platelets, fresh frozen plasma, cryoglobulin, intravenous immunoglobulin, granulocytes, and allogeneic stem cells [12]. However, blood products with higher plasma volume are at the greatest risk, specifically fresh frozen plasma, apheresis platelets, and whole blood. In the FDA reported cases of death due to TRALI, fresh frozen plasma was the most implicated [7]. In one retrospective cohort study from 2007, fresh frozen plasma and platelet transfusions led to a higher incidence of TRALI versus red blood cell transfusion in the ICU population [20]. It remains unknown the exact amount of plasma which must be transfused in order for TRALI to develop. Reports of as little as 10–20 ml of plasma transfused before TRALI development are in the literature; however, plasma volumes greater than 50–60 ml are thought to be the threshold which puts patients at a higher risk [12].

Another important risk factor is the gender of the donor, and preventive strategies in the past 15 years have focused on gender related donor deferral . Female, multiparous donors have allo-immunization from pregnancy. Blood from this particular group of donors has a much higher risk of TRALI development in the recipient secondary to the anti-HLA and anti-HNA antibodies, which bind to recipient antigens and lead to immune-mediated TRALI. The prevalence of antibodies in this population increases with parity. A 26 % approximate frequency of anti-HLA antibodies exist if a female has had more than three pregnancies [21]. Another potential risk factor where studies have shown controversial data is blood product storage time. Experts in the field hypothesize that longer storage times of red blood cells may lead to a higher incidence of TRALI. Experimental models in preclinical trials show a positive correlation between longer blood storage times and TRALI; however, there remains no overt clinical evidence to support the finding [22]. Studies done in the preemie population showed no difference in the incidence of TRALI based on blood storage time. An ongoing study in the adult intensive care unit population is underway that hopefully will help to clarify the importance of blood storage time as a potential risk factor [23].

Incidence

The true incidence of TRALI is unknown secondary to prior lack of a concise definition, the inconspicuousness of the diagnosis, and lack of a structured reporting system. It occurs in all age groups, including children and the geriatric population. It occurs at the same frequency in women and men. Reported TRALI incidence varies between 0.08 and 15 % of patients transfused and 0.01–1.12 % per product transfused, with the higher incidence in the critically ill patient population [24]. Up to 50–70 % of patients in an intensive care unit receive some form of blood product transfusion, and more independent patient risk factors exist in the critically ill population, which may account for this increase in incidence (see section “Risk Factors”). Even though the overall reported incidence of TRALI remains low, it is almost certainty an under-recognized and underdiagnosed condition. In the setting of no gold standard for diagnostic testing, a passive reporting system, and an array of mild cases which do not meet the consensus definition of the disease, TRALI remains under-reported [25]. Despite the underestimated incidence of TRALI, the overall frequency has decreased since the mid-2000s secondary to preventative strategies for plasma and platelet transfusions (see section “Prevention”).

Blood Product Variation

As stated before, all blood products have been implicated in TRALI development, and the incidence of TRALI varies based on blood product components. Products with higher plasma volume have higher incidence of TRALI. Reports reveal incidences at approximately 1/432 whole blood products vs. 1/7900 fresh frozen plasma vs. 1/557,000 red blood cells [12, 22]. However, the incidence of TRALI in plasma products has decreased in the past decade secondary to risk mitigation strategies, leaving the incidence of red blood cell transfusions at a higher rate in the more recent years [26].

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

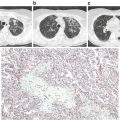

TRALI can present with a large variation in disease severity. By NHLBI and CCC definition 100 % of patients with TRALI have hypoxemic respiratory failure and bilateral pulmonary infiltrates on chest X-ray. Clinically, the most common complaint of patients is dyspnea. However, a large number of patients are critically ill and on mechanical ventilation at the time of blood transfusions leading symptoms to be unhelpful. Despite patients being unable to report symptoms, clinical signs of respiratory distress and failure are present, typically within one to 2 h of a blood transfusion in the majority of patients. Predominately, patients are tachypneic, and in approximately one-third of patients, fever and/or hypotension may develop. Rarely patients may develop new onset hypertension. Most notably in the vital signs, SpO2 should be decreased compared to before the transfusion. Patients on mechanical ventilation may experience a change in pulmonary compliance with an increase in peak and plateau pressures. Pink, frothy secretions from the mouth or endotracheal tube occur in roughly half of patients who develop TRALI. Physical exam should help rule out other etiologies of respiratory distress and should be thorough including a complete lung, heart, and skin exam. Lung auscultation reveals bilateral crackles. Exam findings suggestive of cardiac failure should not be present, such as jugular venous distention and an S3 on cardiac auscultation. It is important to keep in mind that very mild cases of TRALI do exist, which may not fall into the NHLBI and CCC definitions. Mild cases may go unrecognized or present with a similar presentation to the underlying disease process, albeit in a less severe form .

Diagnostic Workup

Practitioners should have a high index of suspicion for TRALI when administering blood products, especially in the critically ill population. Diagnosis can be difficult as there is no gold standard diagnostic test for TRALI. Any person who develops even the least amount of dyspnea or respiratory distress in temporal association with a blood product transfusion should have further clinical and diagnostic evaluation for TRALI. Patients who meet the 2004 NHLBI and CCC definition (Table 11.1) including, new hypoxemic respiratory failure with a PaO2/FiO2 ratio <300 and bilateral pulmonary infiltrates within a 6 h time frame from blood product transfusion, deserve further workup to confirm the diagnosis. One of the goals of the diagnostic workup should be to rule out other possible etiologies for the new development of ARDS, which would then classify the patient as possible TRALI. No diagnostic lab tests are available that confirm the diagnosis of TRALI. An arterial blood gas can be helpful to quantify the degree of hypoxemia. The most common laboratory finding is acute and transient leukopenia, which is thought to be secondary to neutrophil sequestration into the pulmonary vasculature and can be seen in 5–35 % of patients [27]. Thrombocytopenia has also been reported in TRALI. Other laboratory tests, although not diagnostic may also be helpful. In other etiologies of ARDS such as sepsis, a leukocytosis may be present. An elevated brain naturitic peptide can be seen in transfusion associated circulatory overload (TACO) and should not be elevated in TRALI alone. As stated before, a chest X-ray revealing bilateral pulmonary infiltrates is a ubiquitous finding in TRALI, and should be performed for any patient with suspicion of the diagnosis. Historically the pulmonary infiltrates in TRALI were described as “white out lungs.” This may be the scenario in extreme cases; however, both alveolar and interstitial infiltrates have been described in a spectrum from bilateral and patchy to diffuse territories of the lung fields. Despite the findings being nonspecific, the presence of bilateral infiltrates should reach 100 % in this patient population. The chest X-ray is also helpful to eliminate other etiologies of acute respiratory failure, such as pneumothorax .

Blood Bank Reporting

For any suspected TRALI reaction, it is of vital importance the associated blood bank be contacted. Typically a transfusion reaction lab panel is sent, which is directed by the blood bank or transfusion medicine director. The panel includes a complete blood count, haptoglobin, bilirubin, direct Coombs test, and most importantly HLA and HNA antibody testing in the donor blood sample. Anti-HLA and anti-HNA antibodies strongly support the diagnosis of TRALI but are not essential for diagnosis. 15–25 % of TRALI reactions are found to be non-antibody mediated [21]. However, positive antibody results can guide future TRALI prevention if found in the donor blood product (see Section “Prevention”). Antibody testing may take days to weeks for results, and therefore no acute treatment decisions should be made based on antibody testing alone.

Differential Diagnosis

In distinguishing TRALI from other disease states it is important to consider other causes of ALI/ARDS, as well as other transfusion reactions.

Possible TRALI

In 2004, new terminology was instituted as part of the TRALI definition, termed, possible TRALI. This definition takes into account other etiologies of ALI/ARDS, which the patient may be at risk for at the time of blood transfusion (Table 11.1). Since no gold standard diagnostic test exist for TRALI, and it occurs most commonly in the critically ill population with multiple other comorbidities, possible TRALI remains a very relevant diagnosis. If any of these other conditions exist or are suspected, a definitive diagnosis of TRALI cannot be made. Further diagnostic workup should be done in order to eliminate the additional etiologies. Fever can occur as part of TRALI; however, pneumonia, pancreatitis, and sepsis should be suspected as well as an etiology of the acute lung injury. CBC, blood cultures, and chest X-ray can all help to further delineate other disease states. Other conditions such as inhalation, drowning, cardiac bypass, drug overdose , and trauma may be more obvious from history alone.

Other Transfusion Reactions

Various other blood transfusion reactions exist, all of which can overlap with aspects of the clinical presentation of TRALI. Each blood transfusion reaction is managed differently, therefore it is vital to establish the correct diagnosis. The transfusion reaction that mimics TRALI the most is TACO (see Chap. 12). TACO may coexist with TRALI and distinguishing between these two diagnoses may be difficult (Table 11.3). Both conditions present acutely during or after blood product transfusion. Also, both lead to acute respiratory distress and hypoxemia with bilateral infiltrates on chest X-ray. While TRALI’s clinical presentation stems from non-hydrostatic pulmonary edema with capillary leak, TACO is secondary to hydrostatic pulmonary edema. The two conditions are both transient but managed differently. Diuretics are the mainstay of treatment for TACO, but may be detrimental in the treatment of TRALI (see section “Medications”). A positive fluid balance is a risk factor for development of TRALI, and if the positive fluid balance is secondary to compromised cardiac function a higher awareness for TACO should exist. While no definitive test exists to distinguish between the two, diagnostic tools such as elevated jugular venous pressure, an S3 on cardiac auscultation, a transthoracic echo showing depressed cardiac function, and/or an elevated BNP may suggest TACO vs. TRALI. If the patient has a pulmonary artery catheter in place, an elevated pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and/or central venous pressure also favors the diagnosis of TACO. As stated before, chest X-ray is unhelpful in distinguishing between the two diagnoses.

Table 11.3

Differentiating TRALI from TACO

Clinical characteristics | TRALI | TACO |

|---|---|---|

SpO2 | Hypoxia | Hypoxia |

Blood pressure | Usually hypotensive | Usually hypertensive |

Lung exam | Diffuse crackles | Diffuse crackles |

Cardiac exam | +/− Tachycardia | JVD, +S3, +/− displaced PMI |

CXR findings | Bilateral infiltrates | Bilateral infiltrates |

PCWP/ CVP | Normal | Elevated |

Arterial blood gas | Hypoxemia | Hypoxemia |

CBC | Leukopenia, thrombocytopenia | Normal |

BNP | Low/Normal | Elevated |

Echo | Normal Cardiac function | Depressed cardiac function |

Other transfusion reactions may also overlap in clinical presentation with TRALI; however, they are usually more obvious to diagnose. Like TRALI, an anaphylactic reaction from a blood product transfusion may also lead to hypoxia and hypotension. Conversely, the clinical presentation of patients undergoing an anaphylactic reaction may demonstrate signs of airway compromise, such as stridor, bronchospasm, laryngeal edema, and/or wheezing, as well as an associated rash, urticaria, and/or diarrhea, all of which are not seen in TRALI alone. In septicemia from blood product transfusion, which can occur in the setting of contaminated blood products, microbiology is usually positive. Patients may also have a leukocytosis , which is very uncommon in TRALI. Platelets are most commonly associated with septicemia from a transfusion. Lastly, hemolytic transfusion reactions develop acutely with blood product transfusion, but hypoxia and acute respiratory distress are not the mainstay. Fever and hypotension occur in almost all patients with hemolytic reactions and less often in TRALI. Laboratory tests will also reveal a hemolytic pattern, such as a low haptoglobin , elevated unconjugated bilirubin and an elevated lactate dehydrogenase.

Management

Similar to the diagnosis, the management of TRALI is also nonspecific. No exact therapy for TRALI exists, and supportive therapy is the mainstay for treatment. If TRALI is suspected while a blood product is actively being transfused, it should be stopped immediately. All subsequent blood product transfusions should also be held in the acute setting until the diagnosis is made and treatment ensued. As mentioned before, the blood bank or transfusion medicine physician should be notified with any suspicion of TRALI in order to potentially identify and exclude involved donors if relevant antibodies are present.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree