Total Scapular Resections with Endoprosthetic Reconstruction

Martin M. Malawer

Kristen Kellar-Graney

James C. Wittig

BACKGROUND

Tumors arising from the scapula may become very large before diagnosis. Initially, they are often contained by muscle, which protects other tissues within the shoulder girdle. Patients with scapular tumors often present with pain, a mass, or both.

Chondrosarcomas are the most common primary malignancy of the scapula in adults; in children, the most common primary malignancy of the scapula is Ewing sarcoma.

Soft tissue tumors may involve the periscapular musculature and secondarily invade the scapula.

Indications for limb-sparing surgeries of the shoulder girdle include most high-grade bone sarcomas and some soft tissue sarcomas, depending on the tumor extension.

Scapular tumors, such as tumors of the proximal humerus, require careful preoperative staging, appropriate imaging studies, and a thorough knowledge of local anatomy. Selection of patients whose tumor does not involve the neurovascular bundle, thoracic outlet, or adjacent chest wall is required.

It is rare when forequarter amputation is indicated. It is mainly reserved for patients with large, fungating tumors or infected tumors; those in whom limb-sparing resection has failed; and those with tumors invading the major nerves and vessels or the chest wall.

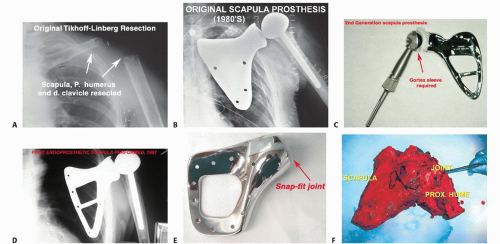

Before 1970, most patients with high-grade sarcomas arising from the scapula were treated with a forequarter amputation.2,3,4,7 The first limb-sparing surgeries for high-grade sarcomas arising from the shoulder girdle were reported by Marcove et al6 in 1977. They reported that the Tikhoff-Linberg resection (FIG 1A) achieved local tumor control and survival similar to that achieved with a forequarter amputation. Most importantly, a functional hand and elbow were preserved. Limb-sparing surgery for patients with high-grade sarcomas in this location soon became standard treatment. Today, the majority of malignancies arising from or involving the scapula can be treated safely with limbsparing surgery in lieu of a forequarter amputation.

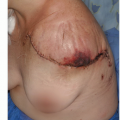

Shoulder motion and strength are nearly normal after a partial scapular resection (type II). However, there is significant loss of shoulder motion, predominantly shoulder abduction, after a total scapular resection (type III), alone or in conjunction with an extra-articular resection of the shoulder joint and proximal humerus (types IV and VI).5 Suspension of the proximal humerus and meticulous soft tissue reconstruction are the keys to providing shoulder stability and a functional extremity. If significant periscapular muscles remain after tumor resection (especially the trapezius and deltoid muscles), a total shoulder-scapula prosthesis may be the optimal reconstructive option (FIG 1B-F).

ANATOMY

The local anatomy of a scapular tumor determines the type of scapular resection and subsequent reconstruction. Because these tumors become quite large before diagnosis, the surgeon should thoroughly inspect the chest wall, axillary vessels, proximal humerus and rotator cuff, and periscapular tissue to ensure that an appropriate procedure is planned.

Sarcomas involving the glenoid, scapular neck, or supraspinatus musculature usually involve the glenohumeral joint and adjacent capsule. Therefore, an extra-articular resection through a combined anterior and posterior approach should be performed for tumors in this location.

Large sarcomas of the scapula with soft tissue extension can involve the axillary vessels and the brachial plexus. Likewise, lymph nodes in the surrounding region should be evaluated to determine resectability.

Suprascapular tumors are difficult to palpate on physical examination. Even sophisticated imaging modalities may incorrectly estimate the extent of these tumors. Tumors in this location can extend into the anterior and posterior triangles of the neck, making resection impossible except in the cases of palliation.

Key Anatomic Structures of the Scapular Region

Neurovascular Bundle

The subclavian artery and vein join the cords of the brachial plexus as they pass underneath the clavicle. Beyond this point, the nerves and vessels are surrounded by a fibrous sheath and can be considered one structure (ie, the neurovascular bundle).

The suprascapular, dorsal scapular, and circumflex scapular vessels form an extensive vascular network around the posterior scapula. Each of these vessels must be ligated and transected to resect the scapula.

Axillary Vessels

The axillary blood vessels are a continuation of the subclavian vessels as they pass underneath the middle third of the clavicle and are called the brachial vessels once they pass the inferior border of the latissimus dorsi muscle. The axillary vessels pass medial and inferior to the coracoid process en route to the proximal humerus. They are surrounded by the brachial plexus throughout their entire course.

The artery yields several branches during its course. The first branch arises as the artery passes over the first rib and is called the supreme thoracic artery. While the artery is deep to the pectoralis minor muscle, the thoracoacromial artery arises followed by the lateral thoracic artery and then the

subscapular artery. The thoracoacromial artery gives rise to four branches, one of which supplies the area around the acromion.

The subscapular artery divides into the thoracodorsal artery and the circumflex scapular artery that wraps around the lateral border of the scapula and tethers the axillary vessels to the scapula.

The anterior and posterior humeral circumflex arteries are the final branches of the axillary artery. They arise at the level of the inferior border of the subscapularis muscle and wrap circumferentially around the humeral neck. The axillary nerve runs with the posterior humeral circumflex vessels. The humeral circumflex vessels tether the neurovascular structures down to the proximal humerus and hence to any neoplasm that arises from this site. Early ligation of the circumflex vessels is a key maneuver in resection of scapular sarcomas because it permits mobilization of the axillary and brachial vessels and brachial plexus away from the tumor mass.

Likewise, ligation of the subscapular artery, or circumflex scapular artery if possible, allows mobilization of the neurovascular structures away from the scapula. Occasionally, there is anatomic variability in the location of the branches of the axillary artery that leads to difficulty in identification and exploration if not previously recognized. A preoperative angiogram can help determine vascular displacement by neoplasm and anatomic variability.

Suprascapular Nerve

The suprascapular nerve arises from the superior trunk of the brachial plexus as it passes over the first rib. It travels posterior through the scapular notch deep to the transverse scapular ligament and supplies the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles.

Musculocutaneous and Axillary Nerves

These two nerves are often in close proximity to or in contact with tumors around the scapula. The musculocutaneous nerve is the first nerve to arise from the brachial plexus. It arises from the lateral cord just distal to the coracoid process, passes through the coracobrachialis, and runs between the brachialis and biceps. It should be preserved, if possible, to maintain elbow flexion.

The path of this nerve may vary extensively. It usually passes 2 to 7 cm inferior to the coracoid process. Tumors that arise from the scapula often displace this nerve anteriorly so that it occupies a position only 1 to 2 mm deep to the fascia. Care should be taken when opening the fascia overlying this nerve in the interval between the coracobrachialis and pectoralis minor muscles. The nerve should be identified and

protected before releasing any muscles from the coracoid process because it can be easily injured during the resection.

The axillary nerve arises from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus and courses, along with the posterior humeral circum-flex vessels, inferior to the distal border of the subscapularis. It then passes between the teres major and minor muscles to innervate the deltoid muscle posteriorly. Tumors of the scapula usually displace and stretch the axillary nerve. The nerve is usually protected from the tumor by the subscapularis muscle.

Radial Nerve

The radial nerve arises from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. It passes anterior to the latissimus dorsi—teres major insertion on the humerus. Just distal to the latissimus dorsi insertion, the nerve courses into the posterior aspect of the arm, just lateral to the long head of the triceps, to run in the spiral groove between the medial and lateral heads of the triceps. The radial nerve must be isolated and protected before resection.

Upper and Lower Subscapular Nerves and Thoracodorsal Nerve

The upper and lower subscapular nerves and the thoracodorsal nerve arise from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus near where the subscapular artery and humeral circumflex vessels arise from the axillary artery. The upper and lower subscapular nerves descend and enter directly into the substance of the subscapularis muscle. These nerves are routinely ligated during a scapulectomy. The thoracodorsal nerve passes with the thoracodorsal artery distally, directly anterior to the subscapularis muscle, to supply the latissimus dorsi muscle. The thoracodorsal nerve can usually be spared during most scapular resections.

INDICATIONS

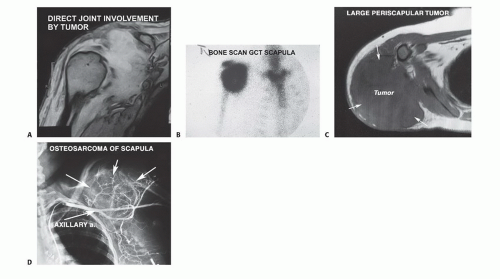

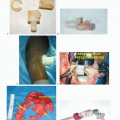

Limb-sparing surgery is indicated for most sarcomas of the scapula (FIG 2).

Soft tissue sarcomas that extend into the scapula can usually be resected with a limb-sparing surgery.

Metastatic carcinoma, myeloma, or lymphoma that has completely destroyed the scapula and has either failed to respond to radiation therapy or chemotherapy or may be treated by limb-sparing surgery

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree