Addiction

Cessation

Cigarettes

e-Cigarettes

Nicotine

Smoking

Tobacco

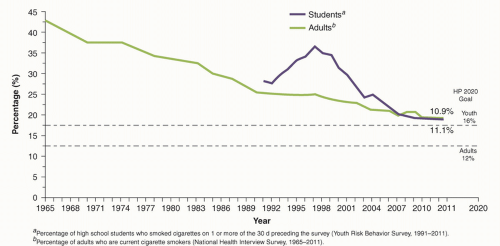

Cigarette smoking continues to decline and is now at the lowest levels recorded in the history of the survey.

e-Cigarettes: This new product has made significant inroads among adolescents. Its prevalence among adolescents is now higher than the prevalence of tobacco cigarette smoking.

College students who use tobacco are more likely to be single, White, and engaged in other risky behaviors involving substance use and sexual activity. Based on the Surgeon General report from 2012, of every three young smokers (i.e., AYAs), one will quit and one will die from tobacco-related causes.1 The tobacco industry has overtly and heavily targeted young adult smokers, sponsoring events in bars and clubs, musical events, and movies popular with young adults.

Each cigarette delivers 1 to 2 mg of nicotine to the smoker.

Each dose of the drug acts on the user within seconds of being inhaled.

smoking is even more dangerous than previously thought. Use of tobacco products can adversely affect virtually every organ system in the body (http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/). Some of these adverse effects include the following:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cardiovascular disease—coronary heart disease, stroke, atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease, aortic aneurysm, early abdominal aortic atherosclerosis in young adults

Cancers—oropharynx, larynx, esophagus, trachea, bronchus, lung, stomach, pancreas, kidney and ureter, bladder, acute myeloid leukemia, colorectal

Diminished bone density and hip fractures

Pulmonary effects—chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and worsening asthma

Gastrointestinal effects—gastroesophageal reflux and peptic ulcer disease

Cataracts, blindness, and age-related macular degeneration

Premature wrinkling of the skin

Periodontitis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree