Thyroid nodules are a commonly encountered clinical entity. Although the majority of thyroid nodules are benign, the risk of malignancy necessitates a thorough evaluation and workup. Evaluation of thyroid nodules is aimed at achieving diagnosis and determining subsequent management: benign asymptomatic nodules undergo monitoring, cytologically abnormal nodules lead to surgical referral for definitive therapy of malignancy or definitive diagnosis of indeterminate nodules, and symptomatic nodular goiters are also candidates for surgery.

In 2009, the American Thyroid Association released guidelines for the management of patients with thyroid nodules, which defined a thyroid nodule as “a discrete lesion within the thyroid gland that is radiologically distinct from the surrounding thyroid parenchyma.”1 Palpable lesions may be appreciated within the thyroid on physical exam, but if a radiologic abnormality is not present, these lesions are not classified as thyroid nodules. Nonpalpable lesions may also be identified on imaging. Such unsuspected, asymptomatic thyroid lesions discovered on imaging or during an operation unrelated to the thyroid gland are termed “incidentalomas” and require workup according to the same guidelines as palpable thyroid nodules.2,3

Thyroid nodules are common, with a reported incidence of 0.1% per year and prevalence of 3% to 7% by palpation on physical exam.4,5 Anatomic imaging techniques, including ultrasound, detect nodules at much higher rates. Prevalence rates of incidental thyroid nodules found on ultrasound are reported to be 20% to 76% in the adult population4,6,7 which correlates with the reported prevalence of 30% to 60% for unsuspected nodules in autopsy series.5,6 Twenty percent to 48% of patients with a single palpable nodule are found to have additional nodules on ultrasound evaluation;4,7 likewise, those with one nodule found on ultrasound, but not appreciated on exam, are frequently found to have multiple additional nodules during the ultrasound examination.7 It is estimated that approximately 500,000 thyroid nodule fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsies are performed annually in the United States.8

Risk factors for the development of thyroid nodules include gender, age, iodine intake, and radiation exposure. Women are approximately four times more likely than men to have both palpable and incidentally discovered thyroid nodules.1,9 Older age and low iodine intake also confer an increased risk of thyroid nodule development. Exposure to ionizing radiation of 2 to 5 Gy, especially as a child, is associated with 2% annual risk of the development of thyroid nodules, with a peak incidence approximately 20 years after the exposure.9

The risk of malignancy in asymptomatic nodules is approximately 5%.5 The risk of malignancy does not vary significantly between those with a solitary nodule and those with multinodular goiter.1,4 Clinical findings, however, that should increase the clinician’s concern for malignancy include the extremes of age (age <20 years or >70 years), a history of head or neck radiation, family history of thyroid cancer, male gender, a firm or fixed nodule, rapid growth, vocal-cord paralysis, or enlarged regional lymph nodes, especially in the setting of a solitary nodule.1,9,10 The size of the nodule does not correlate with the risk of malignancy; the incidence of thyroid cancer in subcentimeter lesions has been found to be equivalent that of larger lesions.11,12

The identification of a thyroid incidentaloma on fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is also a risk factor for malignancy. This is unique to FDG-PET scans, and not observed with incidentalomas found on MRI and CT scans.2,3 Thyroid uptake indicative of a thyroid nodule is noted in 1% to 4% of patients undergoing FDG-PET for other reasons.1,13 Although diffuse thyroid uptake is usually due to autoimmune thyroiditis, focal uptake carries approximately a 30% risk of malignancy.13 Therefore, thyroid lesions identified on FDG-PET require immediate evaluation.

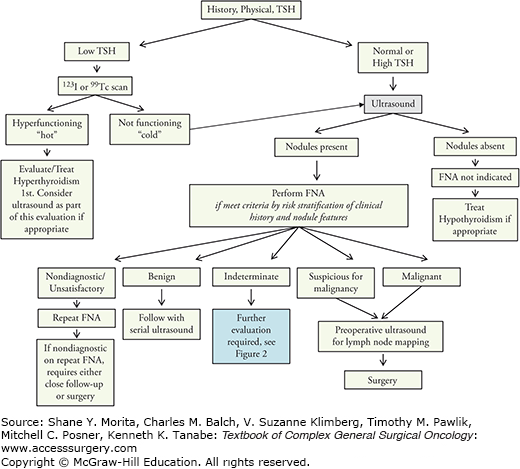

Thyroid nodules can be associated with a wide spectrum of benign and malignant thyroid disease (Table 31-1). They may cause thyroid dysfunction and compressive symptoms, but are most concerning because they carry a risk of malignancy. The clinical challenge in patients with thyroid nodules is to differentiate between the majority of patients with benign disease and the small subset of those with thyroid cancer, so that appropriate treatment can be offered to those with a malignancy while avoiding surgery in those with benign disease. The practical goals of evaluation of a thyroid nodule are three-fold: (1) to identify and treat patients with thyroid cancer, (2) to evaluate for compressive symptoms, and (3) to identify nodules that impact thyroid function. Guidelines from the American Thyroid Association (ATA) in 2009 and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) in 2010 provide algorithms for the workup of these nodules (Fig. 31-1).1,4 It is also anticipated that the ATA will provide updated guidelines in 2014.

Clinical Scenarios Presenting with Thyroid Nodules

| Benign |

| Colloid nodule |

| Simple cyst |

| Hemorrhagic cyst |

| Follicular adenoma |

| Multinodular goiter |

| Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis) |

| Malignant |

| Papillary carcinoma |

| Follicular carcinoma |

| Medullary thyroid carcinoma |

| Hürthle cell carcinoma |

| Anaplastic carcinoma |

| Primary thyroid lymphoma |

| Metastatic carcinoma |

The natural history of solitary benign thyroid nodules is not well-studied and data regarding long-term outcomes is limited.9,14 However, most nodules change little over time; those that do change tend to increase slowly.9,15 A longitudinal study following 330 benign thyroid nodules by ultrasound over a 5-year period (mean follow-up of 20 months) found that a longer time interval between examinations and a lower (<50%) cystic content were the only statistically significant predictors of growth in a multivariate model.15 The median time for nodule increase by 15% in volume was estimated to be 35 months in that cohort. Only 1 of 74 nodules that were reaspirated was found to be malignant.15

Initial evaluation of a thyroid nodule should begin with a history and physical exam, with a focus on elucidating features that suggest an increased potential for malignancy. The location and size of the nodule, as well as the presence or absence of local symptoms, such as pain, hoarseness, dysphagia, and dyspnea, should be documented. Pertinent factors in the patient’s history that predict malignancy include rapid growth, a history of head and neck irradiation or total body irradiation for bone marrow transplant, and exposure to ionizing radiation from fallout in childhood.1

A careful family history of thyroid disorders should also be obtained. A patient with one or more first-degree relatives with thyroid cancer is considered to have a high-risk history. The risk of developing papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) is three times higher in those with an affected parent and is six times higher in those who have a sibling diagnosed with PTC.16 There is a gender disparity in this risk, with the risk increasing to 11 between sisters.16 Familial thyroid cancer syndromes are rare but important to identify when present (Table 31-2). These include familial medullary thyroid cancers (FMTCs) and follicular cell-derived familial thyroid cancers. These familial cancers may occur in isolation or may be a component of a syndrome. FMTC can be a component of multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) 2A or 2B or, in FMTC, can include MTC as the sole hereditary component. Familial follicular thyroid cancer can be seen in Cowden disease, Carney complex, Werner syndrome, and familial polyposis.

Familial Thyroid Cancers and Associated Germline Genetic Mutations

| Syndrome | Gene |

|---|---|

| Differentiated thyroid cancer | |

| Cowden disease (multiple hamartoma syndrome) | PTEN |

| Carney complex | PRKAR1A |

| Werner syndrome | WRN |

| Familial adenomatous polyposis | APC |

| Peutz–Jeghers syndrome | STK11 or LKB1 |

| Familial non-medullary thyroid cancer | Unknown |

| Medullary thyroid cancer | |

| MEN IIA | RET |

| MEN IIB | RET |

| Familial medullary thyroid cancer | RET |

Due to the anatomic location of the thyroid, most thyroid nodules that are larger than 1 cm can be palpated;5 however, nodules of that size located on the posterior aspect of the gland may be difficult to identify on exam, even in experienced hands. Physical exam should include evaluation of the thyroid itself, with attention paid to the number, size, location, mobility, and tenderness of the nodule(s), as well as evaluation of cervical lymph nodes, tracheal deviation, and substernal extension. Physical findings suggestive of malignancy include vocal cord paralysis, cervical lymphadenopathy, and a hard, fixed nodule.

As yet, no serum markers’ diagnostic for differentiated thyroid cancer have been identified for use in the evaluation of thyroid nodules. However, serum thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level plays an important role in the workup of a thyroid nodule and should be part of the initial evaluation ofevery patient with a thyroid nodule. A low TSH significantly decreases the likelihood of thyroid malignancy, as hyperfunctioning nodules rarely harbor thyroid cancer.17 The next step in evaluation of a patient with subnormal TSH, therefore, should be a radionuclide thyroid scan with either123I or technetium99mTc pertechnetate.1 A hyperfunctioning or “hot” nodule is highly unlikely to be malignant and requires no cytologic evaluation; the patient should be evaluated and treated for hyperthyroidism. Isofunctioning or nonfunctioning (“cold”) nodules carry a 5% to 15% risk of malignancy and therefore require further evaluation, which typically includes biopsy.6

Although TSH is not diagnostic for thyroid cancer, recent studies suggest that the risk of thyroid cancer increases as serum TSH concentrations increase. This effect is seen even in patients with TSH levels within the normal range on presentation.18

Serum thyroglobulin (Tg) levels are not sensitive or specific for the diagnosis of thyroid cancer in patients with thyroid nodules; measurement of Tg is not recommended as part of the evaluation of nodular thyroid disease.1,4 It may be extremely useful, however, to measure Tg as a baseline prior to surgery for those patients undergoing thyroidectomy, especially for thyroid cancer. This serves to aid interpretation of postoperative Tg levels, particularly in patients with follicular-derived cancers that may not produce Tg or may be less differentiated. In these scenarios, undetectable Tg in the cancer follow-up period may not be as reassuring for absence of disease.

Calcitonin is a sensitive marker for C-cell hyperplasia and medullary thyroid cancer and has been suggested to improve overall survival when used for screening in patients with nodular thyroid disease.19 Recommendations for the routine testing of serum calcitonin in patients with thyroid nodules differ between the ATA guidelines (no recommendation is made for or against testing) and the AACE guidelines (measurement of a basal serum calcitonin level is recommended).1,4

Thyroid ultrasound is a noninvasive and inexpensive means of evaluating the thyroid gland. It provides valuable information about the number, size, and high-risk features of the nodules. Ultrasound represents the best radiologic modality for the thyroid and in the last decade has become the initial preferred choice for thyroid imaging.

Recent practice guidelines released by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) specify the following indications for thyroid ultrasound pertaining to the workup of a thyroid nodule:20

1. Evaluation of the location and characteristics of palpable neck masses

2. Evaluation of thyroid abnormalities detected by means of other imaging

3. Evaluation of the presence, size, and location of the thyroid gland

4. Evaluation of patients at high risk for occult thyroid malignancy

5. Follow-up imaging of previously detected thyroid nodules

6. Evaluation for regional nodal metastases in patients with proven or suspected thyroid carcinoma before thyroidectomy.

Ultrasound should, therefore, be used to evaluate all patients with a known or suspected thyroid nodule.1,4 Ultrasound should also be used in patients with a history of familial thyroid cancer, MEN2, or head or neck irradiation, even in the case of a normal thyroid gland on palpation. Incidentalomas identified on CT or MRI should be further characterized with ultrasound. An incidentaloma discovered by PET should similarly undergo sonographic evaluation; furthermore, and particularly if the FDG uptake was in a solitary nodule, FNA is required regardless of the sonographic appearance due to the high risk for malignancy.2,3,6 If the FDG-PET uptake was diffuse and further clinical evaluation is compatible with thyroiditis without discreet nodules, management is tailored to the clinical findings and FNA may not be needed. A patient with anterior or lateral neck adenopathy suspicious for malignancy should be referred for ultrasound evaluation that includes the thyroid as well as the cervical lymph nodes due to the risk of nodal metastases from a papillary microcarcinoma.10 Due to the high prevalence of thyroid nodules and the low prevalence of malignancy within them, it is not recommended that ultrasound be used as a screening tool for the general population or for those without clinical risk factors for thyroid cancer who have a normal thyroid gland on palpation.4,10,21

Thyroid ultrasound should be performed with a high-frequency transducer for excellent image quality, with the patient’s neck in gentle hyperextension. Both lobes should be imaged in the longitudinal and transverse planes, and a brief evaluation of the lateral neck compartments should also be performed at initial thyroid nodule evaluation to survey for abnormal lymphadenopathy. This lymph node survey is a new recommendation in the 2013 AIUM guidelines.20 A more thorough ultrasound reexamination of the neck for cervical lymph node “mapping” may be performed again later, if desired, to supplement this initial survey in patients with a biopsy-proven thyroid cancer. Location, size, number of nodules, overall gland vascularity, sonographic features of each abnormality (e.g., echogenicity, degree of cystic change, margins, and calcifications), and the location and size of abnormal lateral neck lymph nodes should be obtained and recorded as part of the ultrasound exam. The AIUM website (www.aium.org) provides a very practical listing of logistics and criteria for ultrasound examination of the thyroid and parathyroid glands. The technical aspects of performing thyroid ultrasound, training, and certification are also available through a number of professional organizations (American College of Surgeons, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and Endocrine Certification in Neck Ultrasound). There are also many options in commercially available ultrasound machines, probes (linear probes are used most frequently), and other components in the set-up of a thyroid ultrasound practice. These have been beautifully summarized in a recent review by Nagarkatti et al.22

Several studies have identified sonographic features that discriminate benign from malignant nodules with a high specificity, although no feature is reliable enough to be used alone.12,23,24 Sonographic features suspicious for malignancy include microcalcifications, hypoechoic appearance, increased nodular vascularity, infiltrative margins, and taller than wide dimensions on transverse view (Table 31-3). The combination of suspicious features improves the predictive value of ultrasound substantially. Nonpalpable nodules with a hypoechoic appearance and at least one other feature concerning for malignancy are at high risk for malignancy and should undergo FNA.12The presence of at least two suspicious features on ultrasound will identify approximately 90% of malignant nodules, whereas benign lesions are highly unlikely to have two or more suspicious features.6,10,12,23 Sonographic features, therefore, can be used to delineate the subset of nonpalpable nodules at high risk for malignancy. In addition, spongiform echotexture, isoechoic appearance, and purely cystic nodules without a solid component are highly suggestive of a benign nodule,1,24 and are thus less likely to require FNA for further evaluation. More so than before, the modern application of thyroid ultrasound is coming to rely more heavily on “risk-stratification” patterns that favor benign or malignant assessment of thyroid nodules to determine the need for FNA. This requires sonographers, particularly clinicians with access to a patient’s medical history-related risk factors, to be familiar with the nuances of sonographic features and their proper interpretation. To illustrate, not every “hyperechoic focus” is a “microcalcification”; the latter implies a judgment of higher risk of malignancy and should be used only when implication is intended.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree