Fig. 46.1

Pretreatment computed tomography scan of the soft tissues of the neck. An irregular shaped mass in the right thyroid lobe measuring 8.7 cm in largest dimension extending around the esophagus and narrowing the airway can be appreciated. Multiple enlarged lymph nodes can also be noted

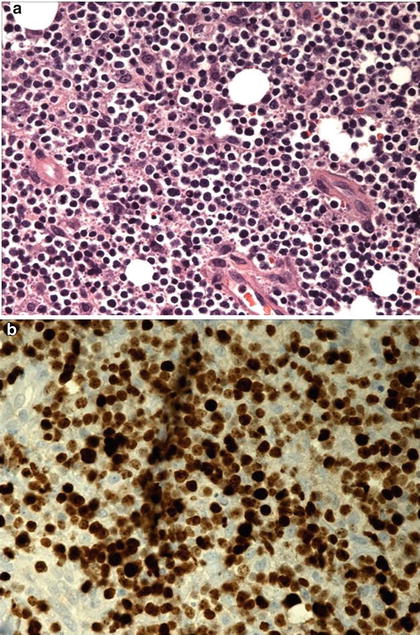

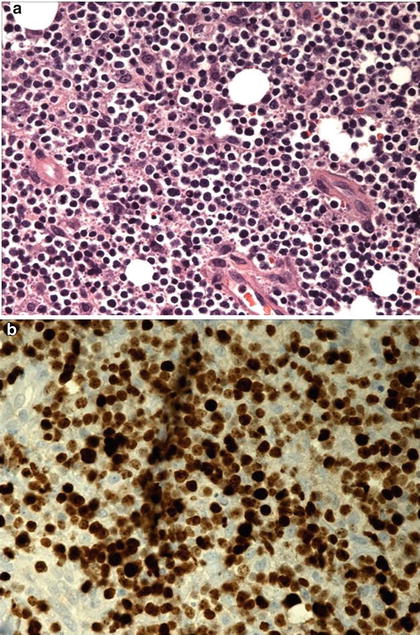

In order to classify the subtype of the lymphoma, an open biopsy of the thyroid was performed under local anesthesia. Immunohistochemistry revealed the tumor to be consistent with B-cell lymphoma, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and a variant of Burkitt’s lymphoma (Fig. 46.2). As part of the work-up, the patient also underwent a bone marrow biopsy which showed no morphologic evidence of lymphoma.

Fig. 46.2

(a) Incisional thyroid biopsy revealed evidence of small-to medium-sized lymphoid infiltrate. (b) Immunohistochemical studies with staining with 100 % labeling with Ki 67 (pattern seen in Burkitt’s lymphoma)

Background of the Disease

Primary thyroid lymphoma (PTL) is rare and accounts for 1–5 % of thyroid malignancies and approximately 2 % of extranodal lymphomas [1, 2]. The mean age of onset is from 60 to 70 years with 50 % of patients presenting later in life in their seventh or eighth decade. There is a distinct female predominance with a female-to-male ratio of 3–4:1 [2, 3]. This is similar to the female predominance in autoimmune Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, and there appears to be a distinct etiologic relationship with PTL. More than 90 % of patients with PTL have elevated circulating thyroidal autoantibodies, noted either before or after the onset of PTL [4–6]. Although the risk of developing PTL is 67- to 80-fold increased in people with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, it is exceedingly rare for any person with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis to develop PTL [5, 7].

The vast majority of PTLs are non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas of B-cell origin. Nonetheless, there have been rare reports of Hodgkin’s and T-cell thyroid lymphomas in the literature [1]. There are several histologic subtypes of PTL including DLBCL constituting 50–70 % of cases, marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) (10 %), follicular lymphoma (12 %), small lymphocytic lymphoma (4 %), Hodgkin’s disease (2 %), and Burkitt’s lymphoma (4 %) [3, 8, 9]. The most common and most aggressive subtype, DLBCL, is associated with a fivefold higher mortality compared to MALT lymphomas that tend to have an indolent clinical course with an excellent prognosis [4, 9, 10]. Therefore, histologic distinction is of paramount importance for determining the best treatment option.

Clinical Presentation, Differential Diagnosis, and Assessment

Most, if not all, PTLs are diagnosed due to a painless ) thyroid mass, and greater than 70 % of cases are diagnosed due to a rapidly enlarging mass in the neck [4]. The most common symptoms are consequent to the mass, including hoarseness, dysphagia, and dyspnea. Occasionally, stridor or superior vena cava syndrome may occur [4, 9]. As expected, with its intrinsic association with autoimmune thyroid disease, it is common for patients to be hypothyroid and require thyroid hormone replacement therapy [11]. Some patients also have constitutional symptoms (classified as “B”) of fevers, night sweats, and unexplained weight loss of more than 10 % body weight in the preceding 6 months.

This abrupt clinical presentation with the associated symptoms not only raises the possibility of PTL but also a soft tissue abscess or infection of the neck, hemorrhage into a thyroid nodule, subacute thyroiditis, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, and metastatic cancer. Therefore, immediate diagnostic discrimination, via history and physical examination, in addition to laboratory, radiology, and cyto-histopathology assessment, is needed due to the significant differences in therapy.

Ultrasonography is often the first imaging modality employed to evaluate a patient with a thyroid nodule or goiter since it is readily accessible, inexpensive, and noninvasive. Ultrasound is effective at delineating intrathyroidal architecture, distinguishing cystic from solid lesions, determining if a nodule is solitary or part of a multinodular gland, and accurately locating and measuring it [12]. Thyroid lymphoma should be suspected in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis when the thyroid begins to rapidly grow. The initial assessment of such patients must be cytologic or histologic. Ultrasound-guided FNA biopsy can suggest or diagnose PTL in a majority of cases [13]. FNA biopsy alone can easily diagnose high-grade lymphomas based on morphologic features, such as noncohesive large-sized cells with basophilic cytoplasm and coarse chromatin pattern within the nuclei. MALT lymphomas and mixed large-cell lymphomas are difficult to diagnose on morphology alone; thus, immunophenotypic analyses must be frequently applied [14]. Nonetheless, the rates of achieving a positive diagnosis via FNA biopsy range from 25 to 80 % [1, 15, 16]. Therefore, in the context of concomitant Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and the potential risk of nondiagnostic FNA, it is sometimes useful to utilize ultrasound-guided core-needle biopsy or even open surgical biopsy under local anesthesia [17].

Thyroid lymphomas may be confused with poorly differentiated thyroid carcinomas on clinical as well as histologic and cytologic grounds. Immunophenotypic analyses, including flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry staining, are usually key to distinguishing between a poorly differentiated epithelial malignancy of the thyroid and a thyroid lymphoma [18]. With the addition of immunophenotypic analyses to FNA biopsy, pathologic studies have reported an improved accuracy rate of 80–100 % [4, 13, 19, 20]. The diagnosis and subtyping of PTLs is made with a combination of morphologic features, immunophenotyping indicating B-cell linage of lymphocytes with tumor clonality, immunohistochemical staining for CD20, restrictive expression of lambda or kappa light chains, and immunoglobulin gene rearrangements [4, 5, 13, 19, 21].

Once a cytologic or histologic diagnosis of PTL is made, full clinical staging is needed. Neck ultrasound is easily performed and can often provide useful information, but magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is far more useful in denoting involvement of other vital structures in the neck [22, 23]. The imaging characteristics of extranodal involvement can be subtle or absent at conventional computed tomography (CT) [24]. Imaging of tumor metabolism with 2-[fluorine-18]fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) has facilitated the identification of affected extranodal sites, even when CT has demonstrated no lesions. More recently, hybrid PET/CT has become the standard imaging modality for initial staging, follow-up (restaging, detection of recurrence), and treatment response assessment in patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and has proved superior to CT in these settings [25]. FDG-PET is even recommended for identifying areas suspicious for tumor transformation (increasing FDG avidity), repeating biopsy, and changing chemotherapy regimens [26]. Bone marrow biopsy should also be performed to rule out marrow involvement [27]. Laboratory assessments should include standard blood work including a complete blood count with differential and a metabolic panel to include albumin, electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine, in addition to measurements of serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels [26]. Prior history of immunosuppressive therapy should also be assessed.

The staging system used for PTL is based on the Ann Arbor modification of the Rye classification system for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. This system is not as predictive of outcomes in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas or in MALT lymphomas; however, it remains the convention for PTL staging [28]. In this system, the subscript “E” applies to a lymphoma arising in an extralymphoid site, as in all PTL cases. Approximately 50 % of patients with PTL have disease confined to the thyroid gland (stage IE), and 45 % have disease in locoregional nodes (stage IIE) [3]. Stage IIIE cases involve nodal disease on both sides of the diaphragm, and stage IVE cases reflect diffuse or disseminated disease.

Management and Outcome

Because PTL is typically responsive to radiation and chemotherapy, the role of surgery is limited [16]. However, surgery continues to play an important role, especially in confirming the diagnosis through open biopsy in those patients in whom core-needle biopsy provided insufficient confirmation of an initial FNA biopsy. Surgery can also provide local control in more indolent subtypes and aid in the palliation of symptoms for large obstructive lymphomas [27, 29].

In general, the best clinical outcomes are seen with multimodal therapy, using sequential systemic chemotherapy and local external beam radiation [30]. The combination chemotherapy regimen usually consists of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (CHOP). Nearly 30 % of patients with clinically localized PTL treated solely with radiation therapy relapse at distant sites, demonstrating the need for systemic therapy [31].

Rituximab is a monoclonal B-cell antibody that selectively binds to the CD20 antigen found on the surface of pre-B and mature B lymphocytes [32]. It is used as first-line therapy both in MALT and in DLBCL patients in combination with CHOP (the so-called R-CHOP regimen) and other anthracycline-based or anthracycline-free chemotherapy regimens [26]. Meta-analysis of published reports on primary nodal lymphoma patients verifies the superiority of adding rituximab to combination chemotherapy [33], and it has been shown to be cost effective when used for that purpose [34]. A number of other monoclonal antibody drugs are entering clinical practice (obinutuzumab, ofatumumab, ibritumomab) [35]. The survival rates range from 13 to 92 % at 5 years [27]. Patients over 65 years of age with large, rapidly growing tumors with high-grade histology have the worst prognosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree