Lymphoma, though primarily a neoplasm of leukocytes, can involve extranodal, nonlymphoid tissue including the thyroid. When the thyroid is involved by widely disseminated lymphoma, the surgeon is rarely involved. This chapter, therefore, focuses on primary thyroid lymphoma (PTL) confined to the thyroid and its regional lymph nodes. Although PTL occurs rarely, familiarity with this disease will benefit the surgeon who may encounter it in the course of the workup of a thyroid mass and may be called upon to aid in its diagnosis and management.

PTL accounts for 1% to 2% of all extranodal lymphomas and approximately 1% to 5% of thyroid malignancies.1,2 It is more common among women, with a 3–4:1 female:male incidence, and it affects individuals between the ages of 55 and 75 years with a peak incidence in the late sixties.3–10

The primary risk factor for the development of PTL is a chronic lymphocytic infiltrate. Accordingly, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis) is strongly associated with PTL, and 20% to 60% of patients diagnosed have preexisting Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.4,6 One group examined clonal relationships between PTL and surrounding Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Using the polymerase chain reaction, they demonstrated substantial genetic homology between PTL cells and the cells from the surrounding thyroiditis, suggesting that cells in the PTL are genetic descendants of the surrounding thyroiditis cells. These results give evidence that PTL evolves from thyroiditis.11 However, only a small percentage of the vast numbers of patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis ever develop PTL.

Lymphomas are characterized broadly as Hodgkin’s lymphoma or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL); NHL comprises the vast majority (98%) of PTL.3 These lymphomas are further classified into subtypes based on the cell of origin (B cell, T cell, or natural killer cell) and the level of differentiation according to the 2008 WHO guidelines for classification of lymphoid tumors.12 Although PTL of T-cell origin does occur, almost all lymphomas of the thyroid have B-cell origins.13 Three subtypes of B-cell NHL comprise 90% of the cases of PTL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma.3

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most common subtype of PTL, comprising approximately two-thirds of the cases. DLBCL tends to be clinically aggressive and is associated with a worse prognosis when compared to other PTL types. DLBCL can coexist with other types of thyroid lymphomas such as MALT in approximately 40% of cases, indicating that some DLBCLs may arise from MALT lymphomas. The pathogenesis of DLBCL likely lies in disorders in the process of somatic hypermutation in which the gene encoding the variable region of antibodies undergoes a high rate of mutation in order to adapt to new antigens.14

The second most common type of PTL is MALT lymphoma, comprising approximately 10% of all cases. Compared to DLBCL, MALT lymphomas are more indolent, present at an early stage and have a better prognosis. MALT lymphomas are commonly associated with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and are histologically characterized by lymphoepithelial lesions, reactivation germinal centers, and frequent plasmacytic differentiation.15

The third kind of PTL is follicular lymphoma. In contrast to DLBCL and MALT lymphoma, follicular lymphoma has classically been described as a very uncommon form of PTL. However, a recent analysis of the SEER database found follicular lymphoma to have an incidence similar to that of MALT lymphoma.3 Follicular lymphoma of the thyroid also has a very high association with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and is histologically characterized by a destructive infiltration of atypical lymphocytes that form follicles. It can be difficult to differentiate follicular lymphoma from MALT lymphoma histologically because lymphoepithelial lesions are seen in both diseases.16 As with DLBCL, aberrant somatic hypermutation has also been strongly associated with follicular lymphoma of the thyroid.14

Almost all patients with PTL present with a thyroid mass. On exam either a discrete nodule or a diffusely enlarged thyroid gland is usually identified.4,6,7,9,17 The mass typically enlarges rapidly over the course of 2 to 3 months, and it may cause compressive symptoms, such as dysphagia, dysphonia, or dyspnea.4,6,7,9 Hypothyroidism is relatively common, being present in 41% to 67% of patients at the time of diagnosis.4,9,17

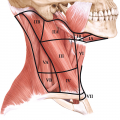

The Ann Arbor staging system is widely used for the staging of NHL, including PTL (see Table 38-1).15,18 Because PTL by definition involves extranodal disease, it will always include the “E” postscript in its staging. The “B” postscript refers to the presence of the associated symptoms. Stages IE and IIE represent locoregional disease, while stages IIIE and IVE represent advanced disease.

Although the Ann Arbor staging system has gained widespread acceptance for NHL, it was originally developed to stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and its prognostic discrimination is greater in Hodgkin’s lymphoma than in NHL. Due to the limited prognostic accuracy of the Ann Arbor staging system for NHL, the International Prognostic Index was developed. It identifies five salient risk factors: age >60 years, advanced disease (Ann Arbor stage III or IV), extranodal disease at more than one site, poor performance status (defined as patient not being ambulatory), and elevated serum LDH level. Patients are stratified into four risk levels based on the number of risk factors present (see Table 38-2). Low-risk patients have a 5-year overall survival rate of 73%, whereas the rate is 26% for high-risk patients.19 Including the histologic subtype of NHL along with the International Prognostic Index improves prognostic accuracy.20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree