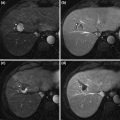

Fig. 1

a Segment VII hepatocellular carcinoma during arterial phase of computed tomography showing a hypervascular tumour before TACE. b Computed tomography image 2 years after TACE. Compact uptake of lipiodol in hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with favourable survival

4 Chemotherapeutic Agents

The most commonly used agents are doxorubicin and cisplatin, followed by epirubicin, and none was found superior to the others in RCTs [9, 18]. There is no proven superiority of any chemotherapeutic agent in transarterial therapies or of combination therapy over monotherapy [9]. The dosing of chemotherapeutic agent also varies among centres. There is no consensus if a standard dose for all patients should be used or a dose adjusted to the body surface area or the bilirubin level or other measure of liver function. The median dose in published trials per session of doxorubicin, cisplatin and epirubicin was 50, 92, and 50 mg, respectively [9]. A published trial failed to demonstrate any difference between standard and low chemotherapeutic doses of mitomycin, epirubicin and carboplatin, except for more frequent adverse effects in the conventional dose group [19].

5 Embolising Agents—Gelfoam, Polyvinyl Alcohol Particles and Drug-Eluting Beads

The most commonly used embolising agent until recently was gelatine sponge particles (gelfoam), which however only provide short-term arterial occlusion that lasts only for 2 weeks [20]. This short-term artery occlusion with what are in effect large particles of 1 mm diameter might be a reason for less effectiveness of embolisation alone compared to TACE in earlier RCTs [13].

However, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles, now used in many centres, result in permanent artery occlusion and also achieve more distal arterial obstruction due to their smaller size (45–150 microns) [20]. In a non-randomised study of PVA versus gelfoam, although there was no survival benefit of any embolising agent, significantly less TACE sessions were required if PVA were used [21].

Drug-eluting beads (DEBs; Biocompatibles, Surrey, UK) have been recently developed in order to provide a combined local ischaemic and cytotoxic effect [22, 23]. Licensed sizes include 100–300 and 300–500 microns. These beads permanently occlude the artery, while ensuring the controlled and sustained delivery of doxorubicin in a predictable manner [24]. Therefore, high intra-tumour doxorubicin retention is achieved, with minimal systemic toxicity [23]. The use of DEB-TACE is a big step towards the standardisation of the TACE technique, but it is the most expensive of TACE-like procedure with yet unproven superiority in terms of the hard end point of survival. The PRECISION V trial was a multicentre phase II RCT with 212 patients that compared DEB-TACE with conventional TACE [25]. In conventional TACE the embolising agent was not standardised, as it depended on the investigator’s choice and therefore varied among gelfoam, PVA particles, Bead Block, etc. Doxorubicin was the chemotherapeutic agent in both arms. The primary endpoint was tumour response at six months according to EASL criteria. However, the superiority hypothesis of DEB-TACE was not shown. Nevertheless, DEB-TACE resulted in improved tolerability and significant reduction in liver toxicity and doxorubicin-related side effects, as the systemic side effects of doxorubicin were greatly reduced, Supplementary analyses showed a significantly higher objective response rate with DEB-TACE in patients with more advanced disease (Child-Pugh B, ECOG 1). This observation seems to be a direct result of the improved safety and tolerability profile that allowed the delivery of DEB-TACE according to schedule to these sicker patients.

6 Frequency of TACE Sessions

The optimal interval between embolisation sessions has not been addressed in any RCT. Existing strategies include either a fixed schedule or repeated sessions when there is radiological evidence of residual vascularity or of progression. In our systematic review we found that the mean number of courses performed for each patient across all series (reported only in 52 of 102 studies) was 2.5 ± 1.5. The median interval between two consecutive courses of TACE was 2 months, but ranged from 4 to 12 weeks [9]. From an oncological point of view, chemotherapy should be administered at 3-week intervals in order to fit to the cell cycle. The currently used schedules might further minimise the efficacy and role of chemotherapy in TACE [26].

7 TACE Versus TAE

While transarterial therapy is now a validated treatment for intermediate stage unresectable HCC, there is still controversy as to which type is the optimal procedure. Many authors believe that the anti-tumuoral effect of TACE is accomplished through the occlusion of the feeding artery of the tumour, while others believe that it is the local chemotherapeutic effect that makes the difference [27]. Experimental studies have shown that embolisation-induced ischaemia triggers the formation of collateral circulation and re-establishment of blood supply of residual tumour after TACE through induction of pro-angiogenic factors [28–30]. Adding chemotherapy to embolisation might theoretically augment the antitumour effect and counteract the stimulation of embolisation-induced neovascularisation [31]. However, in many centres the chemotherapy and embolisation are administered at the same time. It is difficult to be certain that cells rendered ischaemic are able to take up chemotherapeutic agents.

Currently, there are five RCTs comparing TACE with TAE alone [13, 31–34], of which two favoured TACE [13, 31]. We performed a meta-analysis of the first three RCTs [13, 32, 33] which showed no survival difference between the two techniques [9]. It should be noted that gelfoam was used as embolising agent in the first three trials, which could be considered a suboptimal embolising agent. In the two most recent RCTs, there were different results despite the use of optimal embolizsing agents, i.e. PVA particles and DEBs. One RCT randomised 84 patients to either DEB-TACE or embolisation alone using BeadBlocks [31]. Although no survival benefit was shown (1-year survival 86 % vs. 85.3 % in DEB-TACE and TAE, respectively), the DEB-TACE group demonstrated reduced tumour recurrence, better local response and a longer time to progression compared to the embolisation alone group. The second RCT was performed by our group and was a phase II trial of three weekly cisplatin-based TACE versus TAE with the same PVA particles as the embolising agent [34]. In total, 85 patients were randomised, and the primary endpoint was overall survival (OS). Secondary endpoints were progression-free survival (PFS), toxicity and response. The choice of the three weekly schedule was in order to fit to oncological cell cycle principles [35]. The median OS was 16.2 vs. 15.9 months in the TAE and TACE group, respectively. As no statistical significant differences in terms of response or survival were found between the two groups, we calculated that the chance of seeing a survival difference of >2 months between TACE and TAE in a phase III trial was <20 %. Therefore, there was a preplanned protocol not to proceed to a phase III trial. When we repeated the meta-analysis including all the four RCTs published as full papers for the purpose of this review, still no survival difference between TACE and TAE was noted (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

Forrest plot for survival outcomes following TACE or TAE alone in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in four randomised controlled trials to date

It is difficult to comment on the different findings of the two recent studies, as treatment schedules were different. The size of the embolising particles could be a potential explanation, as PVA particles used in our trial were 45–150 microns [34], while Bead Blocks were larger at 100–300 or 300–500 microns in the other RCT [31]. Smaller particles could theoretically result in more selective and total occlusion of the smallest tumour feeding arteries and thus improve efficacy. An alternative explanation could be that DEB-TACE is indeed superior as it consistently delivers chemotherapy in a sustained fashion. Finally, small sample sizes cannot exclude a type II error either way. Clearly, further larger RCTs are needed to clarify this issue.

8 Adverse Effects

The most common adverse effect of TACE is the post-embolisation syndrome, which occurs in 60 % of patients and consists of abdominal pain, fever and elevated liver function tests. It is usually self-limited within 24–48 h [36]. Deterioration of liver function is encountered in a minority of patients, is due to ischaemic damage to the non-tumoural liver, and it can lead to acute liver failure in a few cases. Other complications include ischaemic liver abscess due to colonisation of necrotic tumour, bile duct injury, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, ischaemic cholecystitis, encephalopathy, ascites and contrast or chemotherapy-induced renal failure [9, 11]. Treatment-related mortality was a median of 2.4 % (range 0–9.5 %) in 37 trials involving 2,878 patients [9].

9 Combination of TACE and Percutaneous Techniques

As tumour size increases, the effectiveness of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is reduced partly due to incomplete ablation and the increased blood flow in larger lesions resulting in heat loss and thus less effective ablation. Therefore, it seems reasonable to perform RFA after occluding the hepatic arterial flow supplying the tumour with TACE. This will increase the ablation size of thermal injury as blood flow to and within the tumour has been reduced. There is no randomised controlled trial to address the issue of combining TACE and RFA to date. Cohort studies suggest that the combination in selected patients is beneficial; however, no control groups were used [37, 38]. A small RCT that evaluated the combination of TACE with percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) failed to show a survival benefit versus TACE alone [39]. This is not totally unexpected, as we have shown in our recent meta-analysis that RFA is superior to PEI in tumours measuring more than 2 cm [40].

10 Combination of TACE and Anti-angiogenic Therapy

The multikinase inhibitor sorafenib has antiangiogenic activity and was the first systemic treatment that was found to have a survival benefit in HCC [41]. The SHARP trial enrolled patients with advanced HCC, for which no other treatment option was available [41]. There is strong experimental evidence to support the combination of local therapy with systemic targeted treatment [42]. The latter seems more effective when given continuously. Transarterial embolisation leads to massive localised hypoxia with a central necrosis. In response to this injury, survival and growth factors such as VEGF factors are synthesised in the tissue [43]. Therefore, an effective strategy could be treatment with antiangiogenic therapy before TACE. Neo-vessel formation usually occurs within 3 weeks after the procedure. Thus, scheduling embolisation at predefined intervals and combining antiangiogenic agents with TACE/TAE (and continuing them after the procedure) could either reduce or inhibit neovascularisation and tumour re-growth, thus improving therapeutic efficacy. The preliminary results of a phase II single arm prospective trial of DEB-TACE combination with sorafenib were recently presented in abstract form [44]. In an interim analysis, all 11 patients have experienced partial response or stable disease by EASL and RECIST criteria.

11 TACE in Patients on the Waiting List for Liver Transplantation

Patients currently listed for liver transplantation in most centres fulfil the Milan criteria, i.e. one tumour less than 5 cm or up to three tumours less than 3 cm [45]. As organ shortage leads to increased waiting times in most countries, a strategy for local therapies to prevent tumour growth while the patient is on the list seems prudent. In our centre, we routinely use TACE/TAE in listed patients with HCC irrespective of tumour size. We do not favour RFA due to the possibility of seeding [46]. We have recently shown in a retrospective analysis of the transplanted patients in our centre that TACE has neo-adjuvant therapy in patients transplanted because HCC was associated with less tumour recurrence after transplantation irrespective of histological response [47]. However, there is no conclusive evidence from prospective studies that strategies for therapy on the waiting list influence post-transplant recurrence [48]. A further issue is whether downsizing tumours in patients initially outside Milan criteria so as to make them fit these criteria and then transplant them is an effective strategy associated with low post-transplant risk of tumour recurrence.

12 Conclusions–Future Directions

TACE is an effective treatment in patients with intermediate stage of HCC who are not candidates for curative therapies. Despite the fact that it is not a standardised treatment, with wide variability of type and dosage of chemotherapy and scheduling and number of sessions, it is now a well-established therapy in Child Pugh A patients. There is little evidence that TACE is better than embolisation alone. The permanence of occlusion and the particles size seem to be crucial for the success of embolisation alone. The advent of DEB is helpful in standardising the procedure for TACE; nevertheless, the superiority and cost-effectiveness of this approach over conventional TACE needs to be proved in phase III trials. As the waiting lists for liver transplantation increase because of organ shortage, the effectiveness of using TACE in patients with HCC on such lists for liver transplantation also needs to be determined, also with examination of explant material. The results of the current trials combining sorafenib with TACE are eagerly awaited.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree