Management of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas is challenging as it relies on radiologic and cyst fluid markers to discriminate between benign and pre-cancerous lesions, however their ability to predict malignancy is limited. While asymptomatic serous cystadenomas can be managed conservatively, mucinous cystic neoplasms and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms are more difficult to manage. A selective approach, based on the preoperative likelihood of high-grade dysplasia or invasive disease, is the standard of care. Research is focusing on the development of pre-operative markers for identifying high risk lesions, which will spare patients with low-risk or benign lesions the risks of pancreatectomy.

Key points

- •

Resection should be considered whenever the risk of malignancy is higher than the risk of the operation.

- •

Serous cystadenomas are considered benign and should be followed radiographically, unless symptomatic.

- •

Mucinous cystic neoplasms are typically resected as they are most frequently seen in young women and typically occur in the pancreatic body or tail.

- •

Management of branch duct IPMN is selective with resection indicated for symptomatic lesions and those with high risk or worrisome features.

- •

Main duct IPMN should generally be resected as there is presumed risk of high-grade dysplasia or invasive disease.

Introduction

Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are being diagnosed more frequently given the widespread use of high-quality imaging studies (computed tomography [CT] and MRI). The reported prevalence of incidental pancreatic cysts is about 2.6% on CT imaging and has been reported as high as 13.5% on MRI.

The 3 most common subtypes of cystic neoplasms are serous cystadenoma (SCA), mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN). The latter represent most neoplastic cystic lesions and are of particular importance to surgeons because these lesions are considered precancerous. IPMN and MCN represent the only radiographically identifiable precursor lesions of pancreatic cancer. For detailed discussion of the different classifications, subtypes, and diagnostic evaluation of cystic neoplasms, (See Ferrone CR: Spectrum and classification of cystic Neoplasms of the pancreas , in this issue).

Management of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas is challenging because it involves decision making in the setting of imperfect diagnostic information. The decision between operative resection and radiographic surveillance must balance the risk of a significant operative procedure that has measurable associated mortality with the risk of malignant progression if radiographic surveillance is chosen.

Resection of all pancreatic cysts is no longer appropriate. The vast majority of lesions now identified are asymptomatic, small (<2 cm), and benign. The risk of malignant progression in this group of patients is lower than the risk of operative resection.

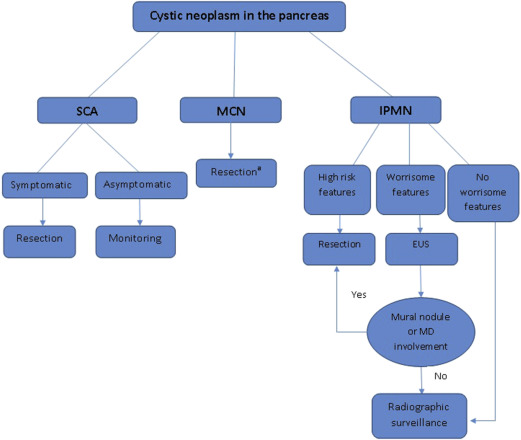

This article focuses on the therapeutic approach to the 3 major subtypes of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas (IPMN, MCN, and SCA), with the understanding that determining the histopathology of a given cystic lesion, based on imaging and cyst fluid analysis, is considered the cornerstone for managing these cysts. Treatment recommendations are usually based on the natural history, biological behavior, and risk of malignancy for each histologic subtype ( Fig. 1 ). Histopathology of small cysts can be hard to determine without resection and represent a clinical dilemma.

Introduction

Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are being diagnosed more frequently given the widespread use of high-quality imaging studies (computed tomography [CT] and MRI). The reported prevalence of incidental pancreatic cysts is about 2.6% on CT imaging and has been reported as high as 13.5% on MRI.

The 3 most common subtypes of cystic neoplasms are serous cystadenoma (SCA), mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN). The latter represent most neoplastic cystic lesions and are of particular importance to surgeons because these lesions are considered precancerous. IPMN and MCN represent the only radiographically identifiable precursor lesions of pancreatic cancer. For detailed discussion of the different classifications, subtypes, and diagnostic evaluation of cystic neoplasms, (See Ferrone CR: Spectrum and classification of cystic Neoplasms of the pancreas , in this issue).

Management of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas is challenging because it involves decision making in the setting of imperfect diagnostic information. The decision between operative resection and radiographic surveillance must balance the risk of a significant operative procedure that has measurable associated mortality with the risk of malignant progression if radiographic surveillance is chosen.

Resection of all pancreatic cysts is no longer appropriate. The vast majority of lesions now identified are asymptomatic, small (<2 cm), and benign. The risk of malignant progression in this group of patients is lower than the risk of operative resection.

This article focuses on the therapeutic approach to the 3 major subtypes of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas (IPMN, MCN, and SCA), with the understanding that determining the histopathology of a given cystic lesion, based on imaging and cyst fluid analysis, is considered the cornerstone for managing these cysts. Treatment recommendations are usually based on the natural history, biological behavior, and risk of malignancy for each histologic subtype ( Fig. 1 ). Histopathology of small cysts can be hard to determine without resection and represent a clinical dilemma.

Serous cystadenoma

Serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are considered benign slow-growing tumors (typically<5 mm/y) with very rare malignant transformation. There have been approximately 30 reported cases of malignant transformation of SCA in the world literature and these malignant SCA reports typically describe locally invasive lesions rather than metastatic disease.

Asymptomatic SCAs should be managed conservatively with radiographic monitoring. Monitoring with MRI or high-resolution triphasic CT should typically be repeated within 3 to 6 months of initial diagnosis, both to confirm the confidence of the diagnosis and to confirm radiographic stability. Once this has been performed, either annual or biennial imaging is appropriate. A recent observational study of 145 subjects with SCA concluded that surveillance for SCA should not be more frequent than every 2 years based on the slow observed growth rate. This study also showed that the rate of growth depends on the age of the cyst rather than the original size at presentation because growth dramatically increased after the first 7 years of surveillance regardless of the original size. Other factors that increased the rate of growth were oligocystic or macrocystic pattern, and a personal history of other tumors.

The exact growth rate of these lesions is unclear because a previous study by Tseng and colleagues reported that there was a difference in the growth rate of lesions less than 4 cm (0.48 cm/y) compared with those equal to or greater than 4 cm (1.98 cm/y). These investigators also reported that cysts greater than 4 cm were more likely to be symptomatic; hence, they recommended resection for asymptomatic patients with SCAs greater than 4 cm. These latter findings have not been observed in patients followed for SCA at the authors’ institution; therefore, we do not use the size of the lesion at presentation as a factor in treatment decision making.

We generally recommend resection in lesions that are clearly symptomatic and for large lesions that are marginally resectable at presentation. Rapid growth, which is rarely observed, is another situation that may warrant resection.

Outcome and Long-Term Recommendations

Following resection, survival is only affected by operative mortality and postoperative complications, rather than the disease itself. In our series of 469 subjects who underwent resection of pancreatic cysts (of all subtypes), the 30-day mortality rate was between 0.5% and 1%. Postoperative surveillance following resection of SCA is generally not indicated. There is no evidence of an increased risk of pancreatic cancer in this group of patients.

Mucinous cystic neoplasms (cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma)

Similar to other cystic neoplasms, the clinical features and natural history of mucinous cysts dictates management as well as the surgical procedure of choice. These lesions are usually identified in women in their 40s or 50s as a solitary cyst in the body or tail of the pancreas. Characteristic radiographic features include a single cyst in the body or tail of the pancreas without significant papillary solid component. Eggshell calcifications may also be present. Cyst fluid analysis typically shows an elevated carcinoembryonic antigen level (mucin production) and low amylase (no communication with the pancreatic duct).

It is known that MCNs have the potential to transform into malignancy and because these typically occur in the tail of the pancreas in young women, surgical resection is often recommended. Given that these lesions are typically unifocal, resection is considered curative because the pancreatic remnant has not been found to be at increased risk for the development of carcinoma. The risk of carcinoma in situ or invasive disease in published series of resected lesions has been reported around 17%. Other features that reportedly increase the likelihood of invasive disease and thus warrant surgical resection are: symptomatic cysts, large size (>4 cm), elevated tumor marker, and presence of solid component or mural nodule.

In elderly patients with multiple medical comorbidities that preclude surgical resection, monitoring of the lesion with serial imaging is an option, especially if there are no worrisome features (MCNs of<4 cm without mural nodules). This is generally done by MRI with MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), or triphasic multidetector CT with 2 mm cuts through the pancreas. Once stability has been determined, annual imaging is appropriate. Notably, multiple studies have demonstrated that invasive MCN usually occurs in older patients, without distinctive imaging characteristics. This is further evidence that we currently are unable to identify invasive MCN before it progresses from noninvasive precursor. Thus, resection should be considered in most patients.

Distal pancreatectomy with lymph node dissection with or without splenectomy is the most common procedure for MCN because most of these cysts are located in the body or tail of the pancreas. Parenchyma-sparing resections (central pancreatectomy) may be performed in small MCNs without features of invasive disease. A recent meta-analysis showed that, compared with distal pancreatectomy, central pancreatectomy is associated with higher morbidity, including higher pancreatic fistula, but lower rate of postoperative endocrine insufficiency. This latter finding is a factor that should be considered because many patients with MCN are in their 30s or 40s at the time of resection. Pancreatic enucleation is also an option and is generally associated with less morbidity, shorter operative time, and lower incidence of endocrine and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Enucleation for these lesions, however, is typically quite challenging because they are often greater than 4 cm in diameter and often thoroughly embedded within the parenchyma with an associated inflammatory infiltrate.

Laparoscopic resection with spleen preservation is feasible and safe for MCNs. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy has been thought to be associated with shorter hospital stay, less blood loss, and decreased overall complications compared with the open approach. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided ablation is still considered investigational and is not recommended for patients with MCN.

Outcome and Long-Term Recommendations

Noninvasive MCN has no risk for distant recurrence after resection and there is no increased risk of pancreatic cancer in the remaining pancreas, with a 5-year survival close to 100%. Thus, these patients do not usually require long-term radiographic surveillance following resection. However, those who are found to have invasive MCN after resection are at risk for distant recurrence. Reported recurrence rates range from 37% to 83% at 5 years, whereas 5-year survival was reported as 57% in a large series of 163 resected MCNs. Per the 2012 international consensus guidelines, recommended follow-up for invasive MCN is similar to resected pancreatic cancer and usually consists of high-quality CT scan (pancreas-protocol scan) every 6 months for the first 2 years and then annually afterward.

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas

IPMNs are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms that arise in the ductal system of the pancreas and may involve the pancreatic main duct (MD) -IPMN, branch duct (BD)-IPMN, or both (mixed-IPMN). Since the recognition of this entity 2 decades ago, IPMNs have been gaining increased attention because they are the most common radiographically identifiable precursor lesion of pancreatic cancer and are presumed to progress from low-grade dysplasia to high-grade dysplasia to carcinoma. This pathway of progression to pancreatic cancer is believed to represent between 20% and 30% of pancreatic cancers. Approximately 40% to 70% of resected IPMN lesions will have either high-grade dysplasia or invasive carcinoma identified at the time of resection.

The 2 main histopathological subtypes of invasive IPMN that have been described are colloid carcinoma, which typically arises in the setting of intestinal-type IPMN, and tubular carcinoma, which generally arises in the setting of pancreatobiliary-type IPMN. There are currently no means of differentiating between these 2 subtypes preoperatively; however, recent studies have suggested that GNAS mutations are strongly associated with colloid carcinoma and KRAS mutations associated with tubular carcinoma. Preoperative distinction between these subtypes may be important because the outcomes following resection differ significantly with reported 5-year survival following resection of colloid carcinoma approximating 75%, whereas resected tubular invasive IPMN has a reported 5-year survival similar to that of conventional pancreatic cancer (15%−25%).

Generally, management of IPMN depends on the result of the initial CT or MRI-MRCP, which will determine whether the patient needs further evaluation with EUS, surveillance, or should undergo surgical resection. Per the 2012 Fukuoka consensus guidelines, high-risk features include an enhancing solid component or MD size equal to or greater than 10 mm. Cysts with either of these features should be resected. Worrisome features include pancreatitis (clinically), cyst equal to or greater than 3 cm, thickened enhanced cyst walls, nonenhanced mural nodules, MD size of 5 to 9 mm, abrupt change in the MD caliber with distal pancreatic atrophy, and lymphadenopathy. Presence of any of these features warrants further work-up with EUS to evaluate for mural nodules or MD involvement. If none of these features are present, no further work-up is indicated but radiographic surveillance is still warranted.

Branch Duct Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms

BD-IPMN is defined as a pancreatic cyst of greater than 5 mm in diameter with communication with the MD without associated MD dilation. BD-IPMN is more common in the elderly and less likely to harbor high-grade dysplasia or invasive disease compared with MD-IPMN. The annual risk of malignancy has been estimated to be between 2% to 3%.

For small, less than 3 cm, BD-IPMN with no high-risk or worrisome features, radiographic monitoring is generally recommended, with resection reserved for symptomatic patients or those who develop worrisome features. The typical follow-up schedule at the authors’ institution for those undergoing nonoperative management includes a short interval scan (3–6 months) to determine stability, followed by either annual imaging or imaging every 6 months. Every 6 month imaging is generally reserved for patients for whom there is some degree of concern, such as a larger BD-IPMN or in the setting of minimal MD dilation (<1 cm).

Indications for resection include the presence of symptoms or any of the high-risk stigmata or worrisome features previously described. The procedure of choice is segmental pancreatectomy or enucleation, depending on the location of the lesion ( Fig. 2 ). A standard resection with lymphadenectomy should be performed for segmental resections. Limited or focal nonanatomic resection is an option as long as there are no preoperative or intraoperative concerns for malignancy.