Author

ECP patients

LOS (PC) (days)

LOS (ECP) (days)

Mortality (PC) (%)

Mortality (ECP) (%)

Morbidity (PC) (%)

Morbidity (ECP) (%)

Zehr et al. (1991–1997) [24]

96

13.6 ± 6.9

9.5 ± 2.8

3.6

0

–

–

Cerfolio et al. (1999–2003)[20]

90

–

7 (median)

–

4.4

–

26.6

Low et al. (1991–2006) [25]

340

–

11.5 (6–49)

–

0.3

–

45

Jiang et al. (2006–2007) [26]

114

–

7 (5–28)

–

2.6

–

16.7

Tomaszek et al.a (2004–2008) [27]

110

9 (4–107)

7 (5–54)

4.6b

4.6b

42.8b

42.8b

Munitiz et al. (1998–2008) [19]

74

13 (8–106)

9 (5–98)

5

1

38

31

Preston et al. (2011–2012) [28]

12

17 (12–30)

7 (6–37)

0

0

75

33.3

Li et al. (2009–2011) [29]

59

10 (9–17)

8 (7–17)

0

2

62

59

Tang et al. (2008–2010) [30]

36

15 (IQR: 12–24)

11 (IQR: 8–15.5)

3.7

5.6

25.9

16.7

Blom et al. (2008–2010) [31]

103

15 (12–26)

14 (11–20)

1

4

68

71

Esophagectomy clinical pathways optimally are initiated at the time of patient’s initial referral, where an initial telephone interview with the patient typically done by the cancer nurse specialist will help to initiate the process of assessment of the patient’s general physiological fitness and nutritional status. Furthermore, this interview provides an opportunity to inform patients and family regarding the relevant steps in their clinical staging investigations and allocation to multimodality therapy and introduce the concept of goal-directed recovery following surgery. The oncology nurse coordinator has an important role in making initial contact with the patient and in coordinating the staging investigations along with appointments with surgery, oncology, and substitutory dietary services, as well as arranged physiological testing. The role of the oncology nurse coordinator has evolved and been assigned greater importance over the past 20 years, as they provide a point of contact for the patient during their initial consultation, staging investigations, treatment, and recovery. The importance of the initial interview by the nurse coordinator is routinely highlighted in patient satisfaction surveys following treatment.

All patients presenting with potentially resectable esophageal cancer should be discussed at a multidisciplinary tumor board, and this includes an assessment of patient demographics including comorbidities, tumor characteristics, and nutritional assessment to allow appropriate allocation of multimodality treatment.

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery has been shown to improve survival in patients with esophageal cancer when compared to surgery alone [32–34]. However, patients must be carefully selected and, in some cases, optimized to be able to tolerate the entire course of treatment involved in trimodality therapy. Nutritional assessment prior to commencing multimodality treatment of esophageal cancer is important to ensure patient compliance and completion of therapy. In patients with major issues with dysphagia, odynophagia, or loss of appetite resulting in significant loss of weight, the patient should be considered for placement of removable endoscopic esophageal stent for obstructive symptoms or pretreatment jejunostomy to facilitate nutritional support during neoadjuvant treatment. In the current era approximately 20 % of patients at our institution receive a pretreatment jejunostomy to address potential nutritional issues and improve tolerance and completion of neoadjuvant treatment. Other groups have reported the successful utilization of percutaneous radiologically sited gastrostomy tubes as an alternative to jejunostomy to address these pretreatment nutritional issues [35]. However, we prefer jejunostomies as we believe they are safer, less likely to compromise the gastric conduit, and can be placed in conjunction with another procedure such as diagnostic laparoscopy or port-a-cath placement. Routine pretreatment nutritional assessment is one illustration of the importance of these clinical pathways, especially when they are initiated at the time of referral and then form the framework to optimize every aspect of the patient’s treatment and recovery.

Pretreatment patient education allows appropriate management of patient expectations and empowers patients and their families to work with their primary caregivers to achieve treatment and recovery landmarks within a goal-directed pathway. Management of patient expectations is an important component of any clinical pathway, as preoperative education must foster patient understanding and commitment to the pathway goals. This issue becomes more important as health systems move towards centralization of complex cancer services, which will inevitably result in patients traveling for especially complex surgical procedures. Within our own institutional esophagectomy series, 48 % of patients travel from more than 150 miles and 26 % from more than 400 miles. We also aim to communicate decisions made at multidisciplinary tumor board to the patient and primary care practitioner within 24 h of the tumor board meeting.

In recent years there have been significant changes in the demographics of patients considered for surgical resection for esophageal cancer at high-volume institutions, with an increase in average age, body mass index, and the incidence of medical comorbidities (Table 3.2). Previous reports of enhanced recovery protocols have specifically highlighted the challenges that elderly patients undergoing esophagectomy represent. Cerfolio et al. [20] demonstrated that 75 % of patients over 70 years of age failed their ‘fast track’ protocol. Moskovitz et al. [36] in a series of 31 patients undergoing esophagectomy over the age of 80 years demonstrated significant poorer outcomes with a longer length of hospital stay (26 (21.1–30.8) vs. 17.9 (16–19.8)) and a greater incidence of perioperative mortality (19.4 % vs. 7.3 %) compared to those under 80 years. However, we have previously published from our own institutional series that selected patients over the age of 80 years can undergo surgical treatment for esophageal cancer within a standardized clinical pathway and have a similar clinical outcome to younger patients, with no incidences of inhospital or 30-day mortality in a series of 32 patients over 80 years [37].

Table 3.2

Evolution in patient demographics; age and medical comorbidities at Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA (1991–2012)

Variable | 1991–1996 (Group 1) | 1997–2002 (Group 2) | 2003–2007 (Group 3) | 2008–2012 (Group 4) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Case no. | 92 | 159 | 161 | 183 | |

Patient age | 64 (16–90) | 64 (15–89) | 66 (32–89) | 66 (37–90) | 0.17 |

M:F ratio (%) | 74 (80.4) | 134 (84.3) | 127 (78.9) | 141 (77) | 0.63 |

BMI | 26 (18–38) | 25 (17–41) | 26 (18–45) | 27 (17–42) | 0.03 |

Charlson (− age) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–6) | 2 (0–5) | 2 (0–7) | 0.005 |

Charlson (+age) | 4 (0–7) | 4 (0–9) | 5 (1–8) | 5 (0–10) | 0.02 |

ASA | 3 (1–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (1–5) | 0.07 |

Arrhythmia (%) | 9 (9.8) | 11 (6.9) | 14 (8.7) | 21 (11.5) | 0.83 |

IHD (%) | 12 (13.0) | 34 (21.4) | 19 (11.8) | 31 (16.9) | 0.51 |

Diabetes (%) | 2 (2.2) | 2 (1.3) | 3 (1.9) | 29 (15.8) | 0.0004 |

Hypertension (%) | 11 (12.0) | 29 (18.2) | 39 (24.2) | 90 (49.2) | <0.0001 |

Liver disease (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | 3 (1.9) | 9 (4.9) | 0.03 |

Renal insufficiency (%) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 6 (3.7) | 6 (3.3) | 0.43 |

COPD (%) | 7 (7.6) | 11 (6.9) | 4 (2.5) | 19 (10.4) | 0.60 |

DVT/PE (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (6) | 0.02 |

PVD (%) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.5) | 8 (4.4) | 0.28 |

A multidisciplinary commitment to the continued revision of these standardized clinical pathways is important to ensure continued evolution and improvement in clinical outcomes. A standardized esophagectomy clinical pathway was first introduced in 1991 at the Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA, and has undergone five revisions to date. These revisions have specifically involved all members of the healthcare team including from surgery, anesthesiology, intensive care unit staff, ward nursing, dietetics, and cancer nurse coordinators.

Specific goals within the pathway that evolved during the past 20-year period (see Fig. 3.1) include:

Improving patient education regarding pathway targets

Adapting surgical approach according to individual presenting patient characteristics

Developing approaches to minimizing blood loss and perioperative fluid administration

Optimizing perioperative pain regimens to maintain targeted postoperative hemodynamics but facilitating postoperative mobilization goals to ultimately mobilize patients on the day of surgery

Assessment and monitoring of nutrition prior to neoadjuvant therapy and esophagectomy

Earlier application of enteric feeding and nasogastric tube removal

Modifying targeted discharge goals from 12–14 days in the early 1990s to 6–7 days in the current era.

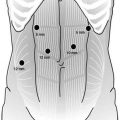

Minimally Invasive vs. Open Esophagectomy

A minimally invasive surgical approach has been shown to reduce physiological stress and improve clinical outcome in several major surgical procedures including colorectal, liver, and pancreatic resections [39–41]. In the UK, there has been a steady increase in the uptake of minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE), with 24.7 % of esophageal cancer resections in 2009 being performed using a hybrid or completely minimally invasive approach [42]. A robust comparative review or meta-analysis of the literature regarding the relative merits of MIE compared to a standard open approach would be challenging due to several inherent limitations of the publications on this subject. The definition of MIE is highly variable and includes laparoscopic abdominal phase with open thoracotomy, open abdominal phase and thoracoscopic approach to thoracic dissection, and totally minimally invasive esophagectomy. Together with the continued variation in open approaches to esophagectomy, this makes direct objective comparison more challenging than in other surgical procedures and the widespread applicability of such comparisons somewhat questionable.

Pooled analyses of the available evidence have identified potential benefits to MIE over open approaches including reduced overall morbidity including respiratory morbidity and length of hospital stay; however, a minimally invasive approach does not appear to influence perioperative mortality [43–45]. It is important to note that these systematic reviews and pooled analyzes are largely based on poor-quality evidence with significant heterogeneity in reported results (Table 3.3) and very limited data regarding long-term survival following MIE. Furthermore, there is significant heterogeneity in the definition of complications following esophagectomy, which is an important limitation when attempting to draw objective conclusions based upon the limited existing evidence [68].

Table 3.3

Comparison of minimally invasive vs. open esophagectomy

Author | Patient no. (MIE/HMIE) | Patient no. (open) | Inhospital mortality (MIE/HMIE) (%) | Inhospital mortality (open) (%) | Anastomotic leak (MIE/HMIE) (%) | Anastomotic leak (open) (%) | Lymph node yield (MIE/HMIE)a | Lymph node yield (open)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bailey et al. [46] | 39 | 31 | 5.0 | 6.0 | NA | NA | 16 ± 1.2 | 17 ± 1.4 |

Ben-David et al. [47] | 100 | 32 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 12.5 | 14 (8–31) | NA |

Berger et al. [48] | 65 | 53 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 14.0 | 11.0 | 20 | 9 |

Biereχ et al. [49] | 53 | 56 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 12.0 | 7.0 | 20 (3–44) | 21 (7–47) |

Blazeby et al. [50] | 124 | 68 | 1.6 | 3.0 | NA | NA | 20.5–34.7 | 29 |

Briez et al. [51] | 140 | 140 | 1.4 | 7.1 | 5.7 | 4.3 | 22 (8–53) | 22 (6–56) |

Gao et al. [52] | 96 | 78 | NA | 3.8 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 17.8 | 18.0 |

Hamouda et al. [53] | 51 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 12 (Early Gp) | 24 |

23 (Late Gp) | ||||||||

Javidfar et al. [54]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|