David A. Greenwald, Lawrence J. Brandt

The Upper Gastrointestinal Tract

Symptoms of gastrointestinal disorders are frequently mentioned by older adults during visits to health care providers, and the digestive diseases producing these symptoms are among the most common hospital discharge diagnoses for older patients in the United States.1,2 As the older adult population expands and their demand for medical care grows, it becomes increasingly important for physicians to be acquainted with the manifestation of diseases of the upper gastrointestinal (UGI) tract in members of this age group.

Oral Cavity

The most proximal of the digestive organs has traditionally been considered to be the esophagus; patients with complaints thought to originate within the oral cavity or pharynx were referred to a dentist or specialist in disorders of the ear, nose, and throat. The oral cavity, however, is examined easily by the general practitioner and may reveal the cause of unexplained or apparently unrelated abnormalities; thus, evaluation of the UGI should begin with the mouth.

Mouth and Nutrition

Changes in the oral cavity occasionally limit the ability of older adults to eat and enjoy a normal diet. Problems with eating sometimes are severe enough to cause malnutrition and prompt a search for a wasting illness.3 The number of general oral health problems has been shown to be a strong predictor of involuntary weight loss in older adults.4

A variety of abnormalities of oral structure and function may contribute to malnutrition. The muscles of mastication may become impaired during aging as the result of a decrease in (lean) body mass.5 Eating occasionally becomes difficult because of tooth loss due to periodontal disease, poor dentition, or loosening of dentures caused by resorption of mandibular bone.6

A reduction in food intake by older adults is sometimes related to a change in taste perceptions. The number of taste buds decreases after the age of 45 years, resulting in a decrease in taste sensation, especially the ability to appreciate salty and sweet foods.7–9 Diminished perception of sour and bitter tastes is associated with palatal defects and typically occurs in patients who wear dentures. Taste sensation may also be altered directly by medications or indirectly affected by a drug’s unpleasant flavor. Agents associated with abnormal taste perception, known as dysgeusia, include tricyclic antidepressants, sulfasalazine, clofibrate, L-dopa, gold salts, lithium, and metronidazole. Medications with anticholinergic properties interfere with taste by reducing salivary gland secretions and producing xerostomia. Age alone, however, is not associated with a reduction in stimulated saliva flow in nonmedicated subjects.10

Although abnormal perception may lead to deficient nutrition, some primary nutritional disorders may be responsible for dysgeusia and glossitis. For example, vitamin B12 and niacin deficiency are associated with a so-called bald or magenta-colored tongue, respectively. Taste sensation and eating habits also are disturbed by processes that interfere with the sense of smell, which typically is diminished substantially by the age of 70 years.11

Vascular Lesions

Diminutive vascular lesions of the UGI are poorly understood and rarely reported. The nomenclature for these lesions is confusing; the terms arteriovenous malformation, vascular ectasia, angiodysplasia, and telangiectasia are generally used interchangeably, with little regard for their true meaning.

The lips are a frequent site of senescent vascular lesions resembling those of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu disease [syndrome]), and involvement often includes the UGI. In addition to this form of small vascular abnormality, patients often have sublingual varices, or caviar lesions (Figure 76-1). The walls of these dilated vessels are thick, but the endothelial lining is hypoplastic.12 In males, sublingual varices may be associated with the occurrence of capillary phlebectasias of the scrotal skin, or Fordyce lesions (Figure 76-2).

Because vascular abnormalities are often responsible for cryptogenic GI bleeding, their presence in the mouth should suggest that similar lesions elsewhere in the GI tract may be responsible for blood loss in such cases.13 However, not every individual with bleeding vascular lesions of the GI tract has involvement of oral structures, and the presence of oral lesions does not preclude the existence of an unrelated distal bleeding lesion.

Oral Mucosa

A number of abnormalities of the oral mucosa are encountered in older patients. These changes may be the result of medical therapy, signify the presence of a systemic disease, or represent premalignant changes.

Candidiasis

Candidiasis is usually caused by the fungus Candida albicans. This organism is part of the normal GI flora, and its presence is not sufficient by itself to produce disease. Mucosal candidiasis occurs only after a change in other constituents of the normal flora or in the presence of an immunologic abnormality. In older patients, the widespread use of antibiotics and immunosuppressive chemotherapy for malignancies is usually responsible for the development of mucosal candidiasis.

The typical oral lesions of candidiasis are soft white plaques that resemble cottage cheese. Characteristically, these plaques can be peeled from the mucosa, leaving the underlying surface raw and bleeding. This observation is important because most other white plaquelike lesions—for example, leukoplakia—cannot be stripped off the mucosa.

A diagnosis of candidiasis is made by smearing scrapings of the lesion on a glass slide, macerating them with 20% potassium hydroxide, and examining this preparation under a microscope for the presence of typical hyphae. A definitive diagnosis can be made by culture on selected media.

Therapy usually consists of reestablishing the normal microbiologic flora by discontinuing antibiotics. In the immunocompromised host and an individual with significant morbidity, topical therapy with nystatin suspensions or troches is usually successful, although treatment with absorbable oral agents such as fluconazole may be required. Antifungal agents may be supplemented by the use of topical anesthetics to provide symptomatic relief (see later).

Stomatitis

Cancer patients treated with radiation or chemotherapy frequently develop painful inflammation and erosions of the oropharyngeal mucosa. Stomatitis complicating cancer therapy is the direct consequence of drug and radiation toxicity to susceptible, rapidly dividing cell populations of the UGI and an indirect consequence of neutropenia, which impairs regeneration of injured tissues. Radiation to the head and neck also causes xerostomia secondary to fibrosis of the salivary glands. An absence of lubrication by saliva further aggravates mucosal damage, and a lack of salivary immunoglobulin A (IgA) permits the overgrowth of bacteria and fungi. Oral lesions may become infected, contributing to persistent injury, discomfort, and poor nutrition and posing a risk of more widespread infection in immunocompromised individuals.

The initial therapy for stomatitis is promotion of good oral hygiene. Brushing and flossing are contraindicated in neutropenic patients because of the risk of disseminated infection. Instead, mouthwashes containing dilute hydrogen peroxide or a salt and soda solution are used to reduce mucosal bacterial and fungal colonization.

A number of therapeutic mouthwash cocktails have been recommended to relieve symptoms, promote healing, and treat superficial mucosal infection in patients with stomatitis.14 Some of these cocktails have been tested in controlled trials, but their use is mainly empirical, based on the known analgesic, antibiotic, and protective effects of widely available liquid medicines. Viscous lidocaine (2%) is frequently used as a topical anesthetic, as is diphenhydramine, which is often mixed with oral antacids or kaolin-pectin. Many formulations include sucralfate suspension because it coats damaged epithelium and promotes the production of mucus and protective prostaglandins. Antibiotics used alone or in combination in mouthwash cocktails to treat superficial infection include chlorhexidine gluconate, nystatin, tetracycline, neomycin, vancomycin, and clindamycin. Hydrocortisone and other glucocorticoids have also been added to reduce inflammation, but rapid absorption across the denuded oral mucosa into the systemic circulation may compromise the patient’s immune defenses. Artificial saliva replacements (e.g., Salivart, Moi-Stir, Xero-Lube) are also available for patients with xerostomia.

Hairy Tongue

So-called hairy tongue is characterized by hypertrophy of the filiform papillae of the tongue and a lack of normal desquamation. In this condition, the color of the tongue varies from yellow to brown or black, depending on staining by exogenous substances such as tobacco or food and on the presence of various chromogenic microorganisms.15,16 Hairy tongue is frequently seen in patients who have had extensive radiotherapy to the head and neck. Although these individuals are usually asymptomatic, some complain of nausea, dysgeusia, and halitosis. On occasion, the lingual papillae become so long that they brush against the soft palate, gagging the patient.

Many organisms have been cultured from papillary scrapings from this entity. There is, however, no proof of a cause and effect relationship with any microorganism, and invasion of the lingual epithelium has not been demonstrated. Species of microorganisms that have been isolated are, in all probability, simply colonizing an already abnormal, excessively papillated tongue.

Therapy for this disorder consists of vigorous brushing of the tongue to promote desquamation and remove accumulated debris. In extreme cases, topical treatment with podophyllin, an alcoholic extract of the Mayapple, may result in a dramatic response.

Leukoplakia

The term leukoplakia was introduced by Schwimmer in 1877 to describe any white plaque. Today, some authors use this term to refer to histologic zones of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and chronic inflammation, whereas others reserve it to describe malignant dyskeratosis and epithelial atypia. Although leukoplakia is considered by many clinicians to be a premalignant condition, its natural history is uncertain because of a lack of uniform definition in case selection. Actually, the term should be abandoned because of its lack of specificity. Any persistent white lesion of the oral mucosa should be biopsied in an attempt to make a specific histologic diagnosis.

Leukoplakia is more common in men than in women and most often occurs during the sixth and seventh decades of life.17 It can be found anywhere in the oral cavity, although it is most common on the buccal mucosa, tongue, and floor of the mouth. Leukoplakia varies in appearance, partly depending on the age of the lesion. Some investigators consider verrucous patches to be of higher malignant potential than smooth plaques, whereas others believe that granular pinkish-gray to red islands, also called erythroplakia, are most likely to be associated with carcinoma in situ or even invasive malignancy. Such controversy stresses the importance of biopsy in the management of all these lesions. Approximately 10% of patients with leukoplakia have or will develop invasive carcinoma in the lesion.17–19

Once the diagnosis of leukoplakia has been substantiated by microscopic examination of a biopsy specimen, therapy is initiated. When dysplasia is present, or when the lesion fails to resolve after a source of physicochemical trauma has been eliminated, treatment consists of ablation.

Epidermoid Carcinoma

Approximately 5% of human cancers arise in the mouth; 95% of oral malignancies are epidermoid carcinomas.18,19 The lower lip is the most common site of malignancy in the area of the oral cavity. Epidermoid carcinoma of the lip occurs almost exclusively in older men; causative factors include actinic radiation, syphilis, and tobacco use, especially pipe smoking.

Carcinoma of the lip varies in clinical appearance and may be bulky or ulcerated. It metastasizes slowly, usually to the ipsilateral submental or submaxillary lymph nodes. Surgical resection or radiation therapy produces equally good results, with cures in approximately 80% of affected individuals. Successful treatment depends on the duration of symptoms, size of the lesion, and presence of metastases.

Within the oral cavity, half of epidermoid carcinomas originate in the tongue, and the rest arise with equal frequency in the palate, buccal mucosa, floor of the mouth, and gingiva. The disease is seen mainly in older adults and occurs most often in men. Factors suspected to contribute to the development of oral cancer include tobacco, alcohol, nutritional deficiencies, syphilis, and miscellaneous forms of physicochemical trauma, such as irritation from pipe stems and dentures. Almost 90% of patients have a combination of predisposing factors.

Intraoral epidermoid carcinomas display a considerable amount of histologic variation, although lesions tend to be moderately well differentiated. Early carcinomas arising in the tongue typically are painless, even though they may ulcerate. Pain develops later, as the lesions grow, especially if they become secondarily infected. Tumors are usually located on the lateral or ventral surface of the tongue. The site of the primary lesion is of prognostic importance because cancers of the posterior aspect of the tongue tend to be more aggressive. Nodal metastases are located on either or both sides of the neck. Tumors also spread by direct invasion. Early detection is mandatory if patients are to survive for more than 1 year after diagnosis.

Keratoacanthoma is a spontaneously resolving benign lesion that is often mistaken for epidermoid carcinoma.20 It occurs most frequently in adults 50 to 70 years of age, involves the upper and lower lips equally, and usually presents as a painful umbilicated lesion, seldom more than 15 to 1.5 cm in diameter. It initially appears as a small nodule which reaches full size within 4 to 8 weeks. It persists as a static lesion for another 4 to 8 weeks, after which the keratin core is expelled and the mass resorbed over a period of 6 to 8 weeks. Recurrence is rare.

Oropharynx

The oropharyngeal phase of swallowing is exceedingly complex, requiring the participation of multiple distinct structures in the mouth, pharynx, and esophagus, coordinated by six cranial nerves and orchestrated by the swallowing center of the central nervous system. After food has been masticated and moistened with saliva, the tongue initiates swallowing by thrusting the food bolus into the oropharynx. The soft palate prepares for the arrival of the bolus by elevating, so that material from the mouth cannot enter the nasal passages. The glottis also shuts, and the epiglottis tilts downward to prevent the bolus from entering the trachea. Relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter in association with contraction of the pharyngeal muscles allows propulsion of food into the esophagus (Box 76-1).21

Striated muscle involved in the oropharyngeal phase of swallowing, like the muscles of mastication, may be impaired during aging by a decrease in lean body mass. A radiographic study of 100 individuals older than 65 years has suggested that 22 of them had pharyngeal muscle weakness as well as abnormal cricopharyngeal relaxation, with pooling of barium in the valleculae and pyriform sinuses. Several individuals also were noted to have tracheal aspiration of barium. All the subjects, however, were asymptomatic. Thus, although functional changes in the oropharyngeal phase of swallowing may occur with aging, these changes have not been identified as a cause of morbidity in older adults.22

Oropharyngeal Dysphagia

Patients with oropharyngeal (cervical or transfer) dysphagia complain of difficulty shifting food from the front of the mouth into the back of the throat or of trouble initiating a swallow once the food bolus has been positioned in the oropharynx. Symptoms may be most severe when the patient attempts to swallow liquids. Signs of transfer dysphagia include nasal regurgitation or the aspiration of oral contents during swallowing as a result of a failure to seal the nasopharynx or trachea by appropriate muscle contraction. Because oropharyngeal dysphagia may be due to a neuromuscular disorder, the patient may display other signs of neuromuscular dysfunction, including dysarthria, nasal speech, cranial nerve dysfunction, weakness, and sensory abnormalities.23

A variety of conditions interfere with the transfer of food from the mouth to the esophagus.24 Mechanical lesions, including tumors, abscesses, and strictures, may block passage of the food bolus or disrupt structures that directly mediate the oropharyngeal phase of swallowing. A neoplasm, infection, or cerebrovascular accident may damage the central nervous system, producing brain stem or pseudobulbar palsy and associated transfer dysphagia. The initiation of swallowing may also be impaired by degenerative diseases of the central or peripheral nervous system, motor end plate, or the muscle itself. Finally, oropharyngeal dysphagia is often caused by a failure of upper esophageal sphincter function. Many of these problems are encountered in older adults.

Cricopharyngeal Achalasia

The term cricopharyngeal achalasia, partly derived from the Greek word meaning “absence of slackening,” is a misnomer, because the cricopharyngeus muscle of patients with this disorder is capable of relaxing. The problem in cricopharyngeal achalasia is failure of the muscle to function in synchrony with other elements of the swallowing mechanism. As a result, the pharyngeal muscles propel all or part of the food bolus against a closed sphincter, producing symptoms of cervical dysphagia.

When cricopharyngeal achalasia is encountered, it is usually in older adults. Many disorders may cause this problem, but central nervous system diseases predominate. The clinical features are generally those of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Depending on the cause, the onset of symptoms may be sudden, as with a cerebrovascular accident, or intermittent, as with more insidious disorders, such as diabetic neuropathy. The natural history of cricopharyngeal achalasia is also variable, again probably reflecting its many causes—dysphagia may diminish, remain unremitting, or follow a relapsing-remitting course. Most individuals with this disorder have more difficulty swallowing liquids than solids. Many patients have a pulmonary presentation with laryngitis, bronchitis, recurrent pneumonia, bronchiectasis, and pulmonary abscesses as the sequelae of otherwise quiet cricopharyngeal dysfunction.25 In some patients, symptoms result in such a fear of eating that weight loss, malnutrition, and psychological problems overshadow the motility disorder.

Postintubation Dysphagia

Special mention must be made of cervical dysphagia occurring as a sequela of endotracheal intubation. Unilateral vocal cord weakness is a common complication of endotracheal intubation and, because the vocal cords are important to the formation of a tight laryngeal seal during the oropharyngeal phase of deglutition, patients with vocal cord weakness may experience coughing and aspiration with swallowing. Individuals who have undergone a tracheostomy also may develop symptoms of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Scar formation from a tracheostomy occasionally prevents normal elevation and anterior rotation of the larynx, causing decreased pharyngeal contraction and incomplete upper esophageal sphincter relaxation during swallowing.

Management of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia

Management of oropharyngeal dysphagia depends only in part on its cause. Any underlying disorder, such as parkinsonism, should be treated. If dysphagia persists despite such therapy, or if significant complications result from impairment of the swallowing mechanism, treatment can be directed at the esophagus itself.

Bougienage of the upper esophageal sphincter with mercury-weighted rubber dilators is beneficial to some patients but often gives only temporary relief. This technique is contraindicated by the presence of a pharyngoesophageal diverticulum because of the high risk of perforation (see later).

Many individuals with cricopharyngeal achalasia benefit from surgical interruption of the upper esophageal sphincter.26 Failure to respond is usually observed in patients with central nervous system disease or peripheral neuropathy, although even they are occasionally relieved of symptoms by this procedure. Serious complications following cervical myotomy are rare. Botulinum toxin injection and balloon dilation also have been used, with limited success. Gastroesophageal reflux or severe distal esophagitis indicating reflux is an absolute contraindication to cricopharyngeal myotomy unless the lower esophageal defect is corrected first.

Pharyngeal Diverticula

Zenker Diverticulum

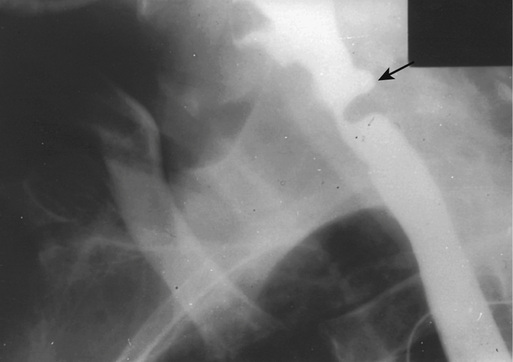

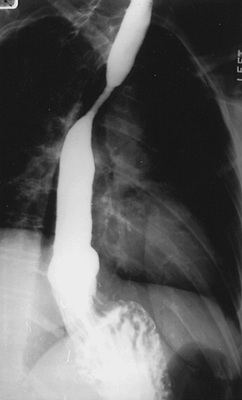

Zenker diverticulum (Figure 76-3) is a posterior herniation of the hypopharynx through the triangular area just above the upper esophageal sphincter where the oblique and transverse fibers of the cricopharyngeus muscle join. It is seen once in every 1,000 routine upper gastrointestinal series and is more frequent in males. Approximately 85% of cases occur in individuals older than 50 years.27

Symptoms of Zenker diverticulum usually develop insidiously. An annoying irritation in the back of the throat is an early complaint, which may be followed later by the more classic symptoms of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Occasionally, an affected individual complains of a noise like the roar of the ocean or washing machine during swallowing. Postcibal and nocturnal regurgitation of undigested food are common complaints. Obstructive symptoms may be caused by associated cricopharyngeal achalasia or, rarely, by compression of the esophagus by a large diverticulum.

Incoordination and incomplete relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter during swallowing have been described in association with Zenker diverticulum, lending support to the theory that cricopharyngeal dysfunction leads to high pharyngeal pressures that result in the formation of hypopharyngeal diverticula. Many patients with a Zenker diverticulum, however, have normal function of the upper esophageal sphincter or even reduced upper esophageal sphincter pressure, suggesting that high pharyngeal pressures may be due to stiffening of the pharyngeal muscles with loss of compliance.28

Zenker diverticula are usually seen during radiologic examination but, when small, may be missed in the posteroanterior view because of superimposition over the main column of barium in the esophagus. This problem can be avoided by rotating the patient during the study (see Figure 76-3). Endoscopic examination of the UGI in the presence of a hypopharyngeal diverticulum may be associated with an increased risk of perforation; however, this danger is minimized by passage of the instrument under direct vision.

Complications include compression and obstruction of the distal esophagus by a large diverticulum, respiratory difficulties caused by aspiration of diverticular contents, and diverticulitis with perforation. Rarely, carcinoma may develop in a Zenker diverticulum.29 Worsening of dysphagia, weight loss, and the appearance of blood in regurgitated material suggest the development of a malignant neoplasm.

The therapy for a symptomatic Zenker diverticulum includes surgical excision alone or cricopharyngeal myotomy, with or without removal of the diverticulum.30 Endoscopic techniques for the treatment of Zencker diverticulum have been well described, with good success rates.31

Lateral Pharyngeal Diverticula

Lateral pharyngeal diverticula, or pharyngoceles, occur with increased frequency in older adults and are especially common in men.32 They develop in the gap between the superior and middle pharyngeal constrictors. Symptoms are the same as those of a Zenker diverticulum. In addition, patients may complain of a neck mass that enlarges with a Valsalva maneuver. Increased intrapharyngeal pressure may be an important causative factor, as exemplified by the frequency of this entity in muezzins and wind instrument players. Surgical repair is safe and effective.

Esophagus

The muscularis propria of the esophagus is composed of striated muscle fibers proximally and smooth muscle fibers distally. The central nervous system governs the activity of the striated muscle by sequential activation of extrinsic nerves. In humans, the dominant mechanism for control of the smooth muscle of the esophagus is unknown; both central and intramural neural pathways have been demonstrated. Orderly peristaltic contractions of esophageal muscle are necessary for normal esophageal function.

Although no information is available about the effects of aging on the regulation of esophageal muscle activity, alterations in esophageal muscle function have been identified manometrically in older adults. These changes were described first in 1964 by Soergel and colleagues,33 who referred to motility disturbances in older adults as presbyesophagus. They studied 15 subjects older than 90 years and found a variety of abnormalities; 13 of their patients, however, had diseases known to affect esophageal motility. Subsequent studies have confirmed that in the absence of other disorders, esophageal motility may be abnormal in older adults, but the only manometric change identified in all the published work to date is a reduction in the amplitude of muscle contractions after a swallow.34–36

Older adults also may be noted to have disordered motility, or tertiary contractions, on a barium esophagram, but this finding is rarely associated with symptoms.37 Because motility changes that develop with aging do not appear to have clinical importance, the diagnosis of presbyesophagus should be abandoned. Older patients with dysphagia should be evaluated for the presence of disease processes involving the esophagus, and complaints should not be ascribed to motility changes occurring as a result of advanced age alone.

Dysphagia and Heartburn

Dysphagia and heartburn (pyrosis) are the principal symptoms of esophageal diseases; patients with esophageal disorders, especially older adults, also may complain of respiratory difficulties, painful swallowing (odynophagia), chest pain resembling the pain of myocardial ischemia, regurgitation, and vomiting.38–40

Dysphagia is caused by impaired passage of food through the esophagus and is experienced immediately after the act of deglutition. Patients often complain that food “sticks on the way down.” Because sensation in the esophagus is referred proximally, lesions at the gastroesophageal junction often appear as symptoms experienced at the level of the sternal notch. When a patient has symptoms that have apparently originated in the area of the proximal esophagus, evaluation of the entire esophagus, often with esophagoscopy and barium radiography, is required.

The pattern of dysphagia frequently suggests the nature of the underlying disease.41 Schatzki observed that a correct diagnosis can be made after taking a careful history in up to 85% of patients with this complaint.42 Thus, intermittent dysphagia connotes a motility disorder or a pliant mechanical obstruction, such as an esophageal web. Progressive dysphagia often represents a neoplasm. Individuals who experience difficulty in swallowing liquids and solid foods usually have a primary neuromuscular abnormality and disordered esophageal motility, whereas dysphagia produced only by solid foods is associated with mechanical obstruction of the esophagus.

Heartburn is a manifestation of the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus and, as its name suggests, is described as being a hot sensation behind the sternum or in the left parasternal area. Pyrosis is relieved by antacids and intensified by bending at the waist or lying supine, especially when the stomach is full. Pyrosis also may be aggravated by some medications, smoking, and ingestion of alcohol, citrus juices, caffeine, chocolate, or peppermint. Discomfort is often accompanied by regurgitation of gastric contents, belching, vomiting, or secretion of saliva (water brash). The nature or extent of esophageal abnormalities associated with gastroesophageal reflux and heartburn cannot be predicted on the basis of the intensity of symptoms, especially in older adults; severe reflux disease, as evidenced by esophageal ulcers, may be present in the absence of substantial symptoms.43,44

Motility Disorders

Esophageal Motility Disorders

After individuals with structural lesions have been excluded, over 50% of adults of all ages with a complaint of dysphagia are found to have esophageal motility disorders.45 These abnormalities may be primary or secondary and are classified according to their manometric signatures. Usually, adults with dysphagia have disordered motility, with nonspecific and inconsistent manometric features.

Nonspecific Secondary Motility Disorders

In older adults, nonspecific disorders of esophageal motility are frequently secondary to a systemic disease. Examples of generalized disorders sometimes responsible for esophageal dysmotility include myxedema, amyloidosis, connective tissue disease, and diabetes mellitus.

Approximately 50% of patients with diabetic neuropathy have abnormal esophageal motility. Findings in these individuals include a decrease in the amplitude of muscle contraction, delayed esophageal emptying, esophageal dilation, and reduced lower esophageal emptying sphincter pressure. In patients with diabetes, the severity of motility changes correlates with the severity of other neuropathic complications; however, affected individuals usually do not have significant dysphagia. Thus, esophageal symptoms in a diabetic must be fully evaluated and not simply attributed to diabetes.

Primary and Secondary Achalasia

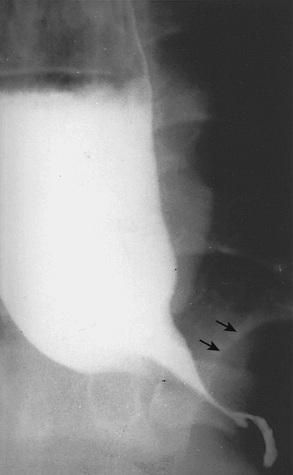

Primary achalasia is the second most common motility disorder diagnosed in patients with nonstructural dysphagia, but it is rare in older adults.46 In those older than 50 years, achalasia is usually secondary to gastric adenocarcinoma (Figure 76-4); pancreatic adenocarcinoma, oat cell carcinoma, reticulum cell sarcoma, and anaplastic lymphoma are responsible for isolated cases.47,48 Manometric findings in secondary achalasia are identical to those in the primary disorder—absence of esophageal peristalsis, usually in association with an elevation of resting lower esophageal sphincter pressure and failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax following an appropriate stimulus. The elevation of resting lower esophageal sphincter pressure typical of achalasia is less pronounced in older adults, who also experience less chest pain in association with this disorder than younger patients.49

Patients with both primary and secondary achalasia may experience progressive difficulties in swallowing. Food collects in the esophagus, which may become distended and tortuous, even when the patient has an underlying carcinoma. In the absence of proximal dilation of the esophagus, a diagnosis of malignancy is favored. When the patient reclines, pooled food flows out of the esophagus back into the pharynx, resulting in coughing and aspiration. Therefore, affected individuals, may present with aspiration pneumonia. In addition to an infiltrate, a chest x-ray may reveal an air-fluid level in the esophagus and absence of the gastric air bubble. Because the presentations of primary and secondary achalasia may be identical, malignancy must be excluded in an older adult with this syndrome. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest and upper abdomen, as well as endoscopy with biopsy of the distal esophagus, are recommended.50 Endoscopic ultrasound may be helpful in differentiating primary from secondary achalasia. Primary achalasia may be treated by pneumatic dilation, surgically, or endoscopically, by peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM).

The pathogenesis of secondary achalasia is unknown. Submucosal infiltration of the distal esophagus by tumor has been noted in some cases, and normal histology has been found in others.51 It is possible that in the absence of tumor infiltration, the motility disorder reflects a paraneoplastic neuropathy; manometric and roentgenographic abnormalities may disappear after resection of a gastric carcinoma or therapy for a lymphoma.52,53

Diffuse Esophageal Spasm

Although primary esophageal motility disorders usually occur in middle-aged individuals, manometric recordings in older adults with intermittent dysphagia occasionally display the pattern of diffuse esophageal spasm.38 In this motility disturbance, the patient has simultaneous, repetitive muscle contractions of prolonged duration that occur spontaneously or after a swallow. Normal peristalsis is present most of the time, explaining the intermittent nature of symptoms, which may be triggered by hot or cold foods, pills, or carbonated beverages. The pathogenesis of diffuse esophageal spasm is obscure; on the basis of case reports, some have speculated that in some cases, this disorder represents a stage in the development of achalasia.

Nutcracker Esophagus and Noncardiac Chest Pain

It is usually assumed that in persons free of significant coronary artery disease with chest pain resembling the pain of myocardial ischemia, symptoms are due to an esophageal motility disorder. Such patients, however, rarely have chest pain during esophageal manometry, and provocative testing may be used to precipitate symptoms. Provocative testing with intravenous edrophonium chloride and infusion of acid into the esophagus causes chest pain in about 30% of subjects with a history of noncardiac chest pain.54 A similar number of patients with noncardiac chest pain have been found to have an esophageal motility disorder, but only 25% of them have symptoms during provocative testing.44 It is often difficult, therefore, to prove that the esophagus is the source of the patient’s complaints.

The most common motility disorder found in patients with noncardiac chest pain is the so-called nutcracker esophagus.44 This abnormality is characterized by peristaltic muscle contractions of extremely high amplitude and long duration in the distal portion of the esophagus. A defect in esophageal transit can be demonstrated in many affected patients using a radionuclide marker. In one large series of individuals with noncardiac chest pain, 50% of patients with a motility disorder had nutcracker esophagus; other symptomatic individuals were found to have diffuse esophageal spasm.44 A causal role for these motility defects in the production of chest pain has not been proved. Many patients with noncardiac chest pain have been found to have musculoskeletal disorders.

A number of medications have been used to treat primary esophageal motility disorders, especially diffuse esophageal spasm and nutcracker esophagus. Nitrates, anticholinergics, calcium channel blockers, or sedatives are occasionally effective in relieving symptoms of dysphagia and chest pain; their benefit in this setting, however, has never been evaluated in an appropriately designed trial. Some patients also obtain relief from dysphagia after bougienage. As noted earlier, pneumatic dilation, surgery and endoscopic techniques are the treatment options for primary achalasia.

Hiatus Hernia

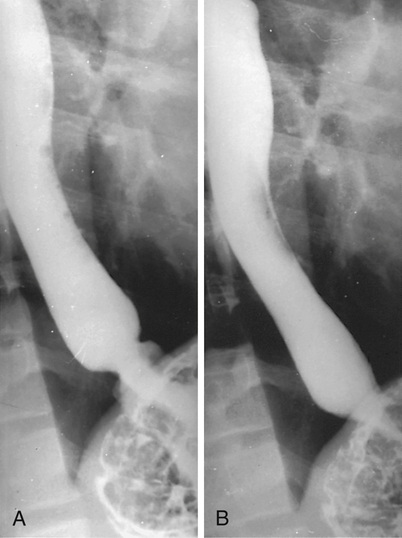

The incidence of hiatus hernia (Figure 76-5) increases with each decade of life, from less than 10% of those younger than 40 years to approximately 40% in the sixth and seventh decades and 70% in patients older than 70 years. Symptoms such as pyrosis and regurgitation formerly attributed to the hernia are now known to be due to lower esophageal sphincter dysfunction. Sphincter dysfunction and gastrointestinal reflux are independent of the presence of a hiatus hernia, and the common sliding hiatus hernia is not by itself considered to be pathogenic.

One type of hiatus hernia that deserves special mention is the paraesophageal hernia (Figure 76-6), an uncommon hernia that usually occurs in persons between the ages of 60 and 70 years. Paraesophageal hernias often result in significant complications and therefore are of major importance. These hernias are frequently asymptomatic or cause only nagging discomfort until mechanical entrapment of the herniated stomach occurs. Such a catastrophe is associated with progressive distention of the incarcerated segment, vascular embarrassment, hemorrhage, gangrene, and perforation. In the absence of contraindications, a paraesophageal hernia demands surgical repair.

Reflux Esophagitis

The only notable change in the lower esophageal sphincter seen with aging is a reduction in the amplitude of postdeglutitive contraction or relaxation. Nevertheless, because the secretion of gastrin, which potentiates contraction of the lower esophageal sphincter, increases with age and, because gastric acid secretion declines with age in many individuals, it is unusual for reflux esophagitis to appear for the first time in older adults.55 The nature or extent of esophageal injury associated with gastroesophageal reflux cannot be predicted on the basis of the intensity of symptoms in older patients.43 Complications of chronic asymptomatic reflux such as stricture formation may be the initial clinical presentation of esophagitis in about 20% of affected older patients. When an older adult complains of the recent onset of pyrosis, other causes of esophageal symptoms, such as candidiasis, must be considered. The therapy of reflux in older patients is the same as in younger patients; however, attention must be paid to the potential development of adverse effects of medications (see later).56

Barrett Metaplasia

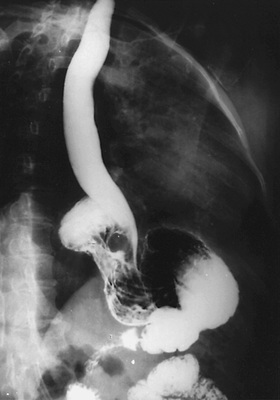

In patients with Barrett metaplasia, the lower esophagus is lined for a variable distance by columnar epithelium, rather than the usual stratified squamous epithelium.57 The metaplastic columnar epithelium may be continuous with the columnar epithelium of the stomach and extend in tongues into the distal esophagus, or it may be present in islands surrounded by normal squamous epithelium. The importance of Barrett metaplasia lies in its association with reflux esophagitis, (deep) esophageal ulcers, (high) esophageal strictures (Figure 76-7), and adenocarcinoma. The metaplastic columnar lining is believed to develop as a consequence of gastroesophageal reflux. Esophageal squamous epithelium damaged by exposure to gastric contents is replaced by a specialized columnar epithelium (intestinal metaplasia), a junctional-type epithelium, or a gastric fundic-type epithelium. Each of these three cell types may be seen alone or in combination with the others.

Most cases of Barrett esophagus probably occur in those between the ages of 50 and 70 years; the exact incidence is unknown. The most common symptoms are those related to the reflux of stomach contents, and the entity is diagnosed best by esophagoscopy with multiple biopsies. The presence of specialized columnar epithelium establishes the diagnosis of Barrett esophagus.57 If the columnar epithelium in the biopsy specimen is one of the other two types, the biopsy must have been made at least 3 cm above the gastroesophageal junction to make the diagnosis. Intestinal metaplasia can be recognized in situ by staining with Alcian blue.

Stricture and neoplasia are long-term complications of Barrett esophagus. There is increasing evidence that cancer arises only in the specialized columnar epithelium. By careful screening using esophagoscopy with directed biopsy every 1 to 2 years, premalignant dysplastic changes can usually be detected.58,59 The development of severe dysplasia or carcinoma in situ requires treatment, such as ablation (using multipolar electrocoagulation, laser coagulation, or argon plasma coagulation) or resection of the involved esophagus. Destruction of the Barrett epithelium by these techniques is successful initially, but recurrence of the Barrett tissue may occur. Therapy of reflux usually results in symptomatic improvement, but regression of the columnar epithelium does not occur without surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree