Locoregional recurrence of a melanoma is defined as recurrence in or around a scar from previous melanoma surgery, or satellite or in-transit metastases. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) groups the latter two (satellites and in-transit recurrences) in the most recent edition of the melanoma staging manual (AJCC 7th edition) as a component of nodal (N) staging.1 Satellite metastases, considered intralymphatic extensions of the primary tumor, are defined as occurring within 2 cm of the primary tumor, whereas in-transit metastases are defined as any dermal or subcutaneous metastases 2 cm or more from the primary tumor but not beyond the draining regional node basin.1 Although satellite metastases and local recurrences are often confused in clinical practice, a true local recurrence is a lesion within or very close to the scar from previous definitive surgery, whereas satellite metastases are somewhat removed from the scar but within 2 cm. The bottom line in the management of all locoregional recurrences, however, is that the treatment algorithms are usually the same. Nevertheless, these patients should be discussed in a multidisciplinary tumor board setting whenever possible. Treatment options for locoregionally recurrent melanoma include surgical resection, local intra-tumoral injections, hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion (HILP), isolated limb infusion (ILI), topical therapies, laser ablation, radiation therapy, and systemic therapies.2

The first decision to be made with any type of locoregional recurrence is: Can the entire recurrence/tumor be removed safely, with minimal morbidity, and the patient rendered NED? Complete surgical resection, in the absence of extensive disease, is considered the standard of care.2 Dong et al report a series of 648 patients with primary melanomas and subsequent local recurrence. In this study, 124 patients (19%) had no further recurrences after surgical resection of the local recurrence. One hundred and ninety-six (30%) developed another local recurrence, 178 (27%) developed in-transit disease, and 150 (23%) eventually developed systemic disease. This shows that close to 20% of patients with a local recurrence are likely to benefit from surgical resection alone. Over 50% of the patients in the series were alive at 5 years, many of those who had recurrences beyond the initial local recurrence having been treated with aggressive local, intra-arterial perfusion-based, or systemic therapies.

Intralesional therapy for locoregionally metastatic melanoma has been practiced for decades. There have been a few recent advances and phase II and III clinical trials that have explored the use of intralesional and topical therapies for metastatic melanoma.3,4 Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) was the first commonly utilized agent for intralesional injections in the setting of in-transit metastases. In 1974, Morton et al reported their experience with intralesional injections of BCG.5 Regression occurred in 90% of the cutaneous lesions that were injected, and 17% of the patients injected had regression of uninjected nodules. A 31% disease-free survival was achieved and this was sustained up to 74 months after injection. The results of later studies were mixed, with some demonstrating improved local response rates with intralesional BCG injections, and others demonstrating response rates that were not significantly different from control arms in the trials. In a large Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial (ECOG 1673), involving more than 700 patients, no survival difference in patients who received BCG with or without dacarbazine compared to the observation arm was demonstrated.6 A subset analysis of the ECOG trial was also not able to identify a difference in survival in patients who converted to a positive reaction after receiving BCG, which was the opposite of a report from the group led by Veronesi.7 Side effects are common with BCG intralesional therapy including severe injection site reactions, seroconversion, and rare systemic infections.

Intralesional interleukin-2 (IL-2) therapy has been studied and is currently used for patients with locally recurrent and in-transit metastases. In a 2003 pilot study, Radny et al evaluated intralesional IL-2 as salvage therapy for patients who failed surgery, regional perfusion, radiation therapy, or systemic chemotherapy. Complete response (CR) was achieved in 15 of 24 patients and partial response (PR) in five additional patients. In total, 209 of 245 metastases underwent CR, with progression of seven lesions. Toxicities were mainly grades 1 and 2. Intralesional IL-2 appears to be associated with local toxicities alone and no systemic side effects are seen. IL-2, as a local therapy, may be a useful adjunct for treatment of in-transit metastases or recurrent melanoma, but as with intralesional BCG, the time-intensive nature of delivering this therapy (multiple injections of lesions numerous times per week until resolution of the lesions) and its high cost may be prohibitive.

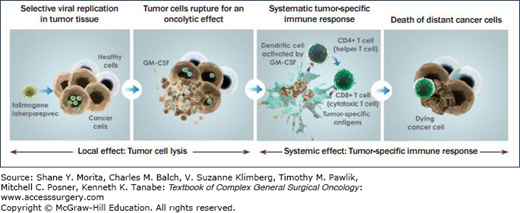

A phase II trial exploring the intratumoral use of a HSV type I virus encoded with the gene for Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), Amgen) was completed in 2009.3 (Fig. 16-1) The results of that trial showed that in 50 patients with stages III and IV melanoma, there was an overall response rate by RECIST criteria of 26% (CR n = 8; PR n = 5), and regression of both injected and distant (including visceral) lesions was noted. Ninety-two percent of the responses were maintained for 7 to 31 months. Ten additional patients had stable disease (SD) for greater than 3 months.3 The recently completed phase III clinical trial of T-VEC transfected with GM-CSF was presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Congress in 2013, with favorable results. The late-breaking ASCO abstract demonstrated the therapeutic benefit of T-VEC against melanoma in a phase III trial where the intratumoral injection of the GM-CSF encoded virus significantly improved the durable response rate compared with subcutaneous GM-CSF alone in patients with metastatic disease (16.3% vs. 2.1%; p < 0.0001).

The phase III study, OncoVex Pivotal trial in Melanom (OPTiM) enrolled 436 patients with 295 being randomized to T-VEC and 141 to GM-CSF over a 2-year period. The primary endpoint of the study was durable response rate (DRR) which is defined as an objective response (PR or CR) lasting at least 6 months within the first 12 months of treatment. Overall response rate (ORR) and overall survival (OS) were secondary endpoints. The DRR was significantly higher in the T-VEC group being 16.3% compared to 2.1% in the GM-CSF group (p < 0.001). The ORR was 26.4% in the T-VEC group versus 5.7% in the GM-CSG group (p < 0.001). Overall survival was similar between groups at a median of 23.3 months for T-VEC and 18.9 months in GM-CSF (p=0.051). The authors did perform a subgroup analysis which showed differences in OS between treatment arms when looking specifically at stage IIIb, IIIC, and IVa patients, at a median of 33.1 months for those treated with T-VEC compared to 17 months for GM-CSF (p < 0.001). The FDA approved T-VEC for use in late 2015.

Allovectin-7 (Vical, Inc) is a plasmid encoded with the human leukocyte antigen-B7 and beta-2 microglobulin genes. A phase II study was conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of intralesional injection of Allovectin-7 in patients with metastatic melanoma. Eligible patients had stage III or IV metastatic melanoma that was recurrent or unresponsive to prior therapy. Patients received six weekly intralesional injections followed by 3 weeks of observation and evaluation. Overall response was assessed using RECIST guidelines. Patients with stable or responding disease were eligible to receive additional cycles. One hundred and thirty-three patients were evaluated for safety and 127 patients were evaluated for efficacy. Fifteen patients (11.8%, 95% CI: 6.2-17.4) achieved an objective response with a median duration of response of 13.8 months and a median time to progression of 1.6 months. Based on these data, a phase III study was conducted comparing intralesional injection of 2-mg Allovectin-7 to dacarbazine or temozolomide, with a primary outcome of durable and sustained regional response at 24 weeks after initial response. The phase III trial, which was completed in 2013, failed to show a significant improvement in objective response rate (its primary endpoint) or in overall survival (secondary endpoint) when compared to dacarbazine or temozolomide.

The results of a phase II study exploring the effects of PV-10 (Rose Bengal, a xanthine dye, Provectus, Inc)8 were presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) meeting in 2012. Eighty patients were treated in this trial, and an objective response was seen in 51%, with a CR in 25% and a PR in 26%. Sixty-nine percent of the patients exhibited disease control (CR, PR, and SD). A bystander effect, where uninjected distant lesions exhibited a response, was seen in 33% of patients. This bystander effect correlated with the outcome in treated target lesions, with an objective response in a bystander lesion seen in 61% of those patients achieving CR or PR in their target lesions versus an objective response of 18% in bystander lesions in subjects that did not achieve a response in their target lesions. Stage III subjects experienced a substantially higher target lesion response rate (60% objective response and 79% disease control) versus stage IV subjects (22% and 33%, respectively). Median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were not reported. Thompson et al further reported an analysis of this data from this study, showing that 50% of patients achieved a CR when lesions were injected.9 A manuscript providing full details of this trial has been submitted for publication. A phase III trial began in mid-2015. The phase III will compare, in a randomzed controlled trial, single agent intralesional PV-10 to dacarbazine or temozolomide to assess treatment of locally advanced cutaneous melanoma in patients who are BRAF V600 wild-type and have failed or are not otherwise candidates for checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy (Fig. 16-2).

FIGURE 16-2

A clinical example of a patient treated with PV-10. This is a male of age 73 with stage IIIB in-transit melanoma of the left lower extremity recurrent after surgical intervention (PV-10 started 1.6 months after resection). Eleven lesions (6.0-cm sum diameter) injected with 1.1-mL PV-10 at Day 0 (single bystander lesion not injected); 7 lesions injected with 1.0-mL PV-10 at Week 8 (5.1-cm sum diameter); and 3 lesions injected with 1.3-mL PV-10 at Week 16 (3.4-cm sum diameter). Subject achieved CR in all injected lesions at Week 36 and confirmed CR in all lesions (including uninjected bystander) at Week 52. (Reproduced with permission of Provectus, Inc.)

Diphencyprone (DPCP) is an immunomodulatory cream that has been used historically as a contact sensitizer to treat alopecia areata and warts. DPCP is hypothesized to work via immunomodulation and activation of the thymus-derived TH17 lymphocytes.4,10 Single case reports and small series in the literature indicate that DPCP is a well-tolerated and effective treatment for patients with extensive dermal and cutaneous metastatic melanoma. In one study by Damian et al, there was a 100% response in a small series of seven patients treated with DPCP (4 CR and 3 PR).10 Further studies with topical DPCP are ongoing.

Imiquimod is a topically applied immunomodulator and toll-like receptor agonist that activates the TLR7 and induces cytokine secretion that leads to downstream activation of effector cells and Th1 lymphocytes. Its use has also been explored for the treatment of in-transit melanoma metastases.11,12 Several small series investigating topical application once or twice daily either alone or in combination with other agents like topical 5-fluorouracil have reported regression rates of up to 90% for superficial lesions treated over the course of months.13,14 No regression of bystander lesions or distant metastases was noted in these reports.

Another technique used to treat locally recurrent and locoregional metastatic melanoma is electroporation, also known as electrochemotherapy (ECT). ECT uses electrical pulses delivered via an array of needle electrodes placed directly into the metastatic tumor mass to create cell membrane permeability, with the concurrent intravenous or intralesional delivery of cytotoxic drugs, most commonly cisplatin or bleomycin.15,16 The increase in cell membrane permeability and local vasoconstriction resulting from the ECT increase the intracellular delivery of the chemotherapy agent. The use of ECT dates back several decades. An early report by Glass et al on its use in five patients with 23 melanoma metastases showed an overall response of 95%, with 75% of lesions showing a complete response.17 A large multi-institutional study of the European Standard Operating Procedures of Electrochemotherapy (ESOPE) was presented in 2006. This study enrolled 102 patients who had ECT treatments combined with either intravenous or intralesional bleomycin or intralesional cisplatin. An overall response rate of 84.8% and CR rate of 73.7% were observed.16 The advantages of ECT include a minimal side effect profile, other than local soft tissue effects, skin irritation and ulceration, and the ability to perform the procedure in selected patients under local anesthesia. The use of ECT for palliation of larger bleeding lesions (usually up to 3 cm) is attractive when other local or regional therapeutic options are unavailable. ECT can even be used in the setting of prior radiation.16

Hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion (HILP) as originally described by Creech et al in 1958 is a surgical method of isolating an affected extremity and treating the in-transit metastases using high-dose chemotherapy and avoiding systemic drug exposure.18 HILP entails dissecting and isolating the femoral or external iliac vessels for lower extremity disease or the subclavian or axillary vessels for upper extremity disease. A regional lymph node dissection can be performed if clinically indicated at the time of vascular dissection. The vessels are directly cannulated and the limb is isolated via a tourniquet, and by ligating collateral vessels. The chemotherapy is then infused and circulated throughout the limb via a cardiopulmonary bypass machine, which is used to heat and oxygenate the perfusate. This technique allows for drug concentrations 15 to 25 times higher in the target tissue than can be achieved by systemic administration. The technique spares the patient from the common toxicities associated with systemic chemotherapy. After the 60-minute perfusion, the perfusate is washed out from the limb with 2 L of a balanced electrolyte solution. Isolation of the limb also allows regional hyperthermia (39°C to 41°C) to be achieved, which has been shown to substantially augment the effects of the delivered chemotherapy.19

The chemotherapeutic agents most widely used in HILP are melphalan (in the United States and Europe) combined with tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) (Europe).20,21 Results from multiple studies show overall response rates to be 80% to 90% and CR rates for melphalan-based HILPs to be as high as 60% to 70%.22,23 When TNF is added to melphalan, improved CR rates of 60% to 80% have been reported, but the data are not consistent throughout the literature. A large multicenter clinical trial in the United States (ACOSOG Trial Z0020) of HILP with melphalan versus melphalan plus TNF, and a study in Europe using the same agents failed to show significant differences in CR rates between the treatment groups.20,21 The ACOSOG Z0020 trial showed CR rates of only 25% and 26% in the melphalan and melphalan plus TNF groups, respectively.21 A study by Noorda et al comparing the same agents (melphalan vs. melphalan plus TNF) showed a CR rate in the melphalan HILP group of 45% versus 59% in the melphalan and TNF group, but the difference was not statistically significant.20 The ACOSOG Z0020 trial also reported a significantly higher number of complications in the melphalan plus TNF group versus melphalan alone (16% vs. 4% grade IV adverse events, p = 0.04). At this time, TNF is not approved for regional therapy of in-transit metastases in the United States. Considering that ILI (see section below) is a less invasive alternative to HILP, some investigators have turned to using ILI before attempting HILP for regional therapy treatment naïve patients.

Morbidities from HILP with or without TNF can be significant and can be attributed to the local effects of the chemotherapy itself, the addition of hyperthermia, systemic leakage of the chemotherapy, or the surgical intervention itself.24,25 The local effects include skin and soft-tissue damage ranging from mild erythema and epidermolysis to extensive tissue damage requiring fasciotomy, and severe damage requiring limb amputation in 0.5% to 1.5% of cases.26 Vascular complications occur in up to 10% of patients.26 Lymphedema is the most commonly reported morbidity and occurs in 12% to 36% of patients.26 Tissue temperatures higher than 40°C or a greater concentration of melphalan are significant risk factors for developing local tissue damage.24 Systemic effects such as myelosuppression and hypotension occur when the melphalan leaks from the isolated limb or when the limb washout is inadequate. If TNF is used in the perfusate, then the toxicities can be even more severe. During HILP, the patient is continuously monitored for chemotherapy leakage from the limb during the perfusion using radiolabeled red blood cells (RBCs) that can be measured systemically by a precordial probe. Lastly, the surgical morbidity is well defined for any lymph node basin dissection, this includes but is not limited to infection, lymphedema, and paresthesias.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree