Darius S. Francescatti and Melvin J. Silverstein (eds.)Breast Cancer2014A New Era in Management10.1007/978-1-4614-8063-1_16© Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014

16. The Surgical Management of Invasive Breast Cancer

(1)

Department of Breast Surgery, St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital Center, New York, NY, USA

(2)

Department of Surgery, Beth Isreal Medical Center, New York, NY, USA

(3)

Division of Breast Surgery, Appel-Venet Comprehensive Breast Service, Beth Israel Medical Center, 10 Union Square East, Suite 4E, New York, NY 10003, USA

Abstract

Since the development of the Halstead radical mastectomy more than 120 years ago, great strides have been made in the surgical management of breast cancer. Many breast cancers are detected at an early stage, and are often treated by breast conservation. Recent surgical advances and popularization of oncoplastic techniques have evolved, further improving the cosmetic outcome after lumpectomy. This chapter will review the role of surgery in the treatment of invasive breast cancer.

The surgical treatment of breast cancer has evolved significantly over the past century. Prior to the 1890s patients diagnosed with breast cancer succumbed to their disease. William Halstead [1] is credited with development of the radical mastectomy, the first surgical treatment for breast cancer. Over the next 120 years advances in breast cancer screening and surgery led to the discovery of smaller, often nonpalpable, breast cancers. The radical or Halstead mastectomy, involves resection of breast, pectoralis major and minor muscles, and axillary lymph nodes. Halstead reported a 3 % local recurrence rate and 40 % 5 year survival. This surgery carried great morbidity and lymphedema was a frequent sequela. This remained the gold standard for breast cancer surgery from the 1890s to the mid-twentieth century. At this time, surgeons recognized the functional and cosmetic morbidity of the Halstead mastectomy and sought an alternative.

In 1948 Patey and Dyson [2] published their series of women who underwent the first version of the modified radical mastectomy. Their operation removed the breast, pectoralis minor muscle, and axillary lymph nodes, but left the pectoralis major muscle intact. They reported no difference in disease free survival or overall survival in patients who underwent a modified radical mastectomy compared with the radical mastectomy group. However, other surgeons were simultaneously advocating more radical surgical techniques including dissection of the internal mammary lymph nodes. In the late 1960s, Jerome Urban [3] and Everett Sugarbaker [4] described the extended radical mastectomy which involved resection of the breast, pectoralis major and minor muscles, axillary lymph nodes, and internal mammary lymph node chain.

The present day modified radical mastectomy was popularized by Hugh Auchincloss [5] in 1970. Auchincloss noted no difference in disease free survival and overall survival when both pectoralis muscles are left intact. This operation is still performed today for locally advanced invasive breast cancer. Debate over the appropriate surgical treatment led to a call for scientific evidence. Breast cancer treatment was further revolutionized in 1977 when the results of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP) B-04 clinical trial were published. Patients were compared in randomized fashion to radical mastectomy to total mastectomy with or without chest wall irradiation. The NSABP B-04 showed no significant difference in overall survival between these groups [6]. This pivotal trial established that total mastectomy with or without radiation was equivalent to a radical mastectomy with regard to overall survival.

The NSABP B-06 was a prospective randomized trial comparing the overall survival and recurrence free survival in patients who underwent total mastectomy, segmental mastectomy, or segmental mastectomy followed by breast irradiation [7] Fischer concluded segmental mastectomy followed by breast radiation was an acceptable treatment for early stage breast cancer. Twenty-year follow-up revealed 14.3 % locoregional recurrence rate in the segmental mastectomy with radiation arm versus 10.2 % in the total mastectomy arm. These results further validated segmental mastectomy with radiation as a treatment for early stage breast cancer [8]. In Milan, Veronesi and colleagues [9] conducted a randomized trial comparing the long term outcomes of patients who underwent a radical mastectomy with those who underwent breast conserving surgery followed by radiotherapy. Twenty-year follow-up was reported and they concluded no significant difference in the rate of distant metastases and overall survival between the two groups [10]. These landmark studies confirmed breast conserving surgery is equivalent to total mastectomy with regards to overall survival.

In conclusion since the development of the Halstead radical mastectomy more than 120 years ago, great strides have been made in the surgical management of breast cancer. Many breast cancers are detected at an early stage, and are often treated by breast conservation. Recent surgical advances and popularization of oncoplastic techniques have evolved, further improving the cosmetic outcome after lumpectomy. This chapter will review the role of surgery in the treatment of invasive breast cancer.

Invasive Breast Cancer

The two most common types of invasive mammary carcinoma are invasive ductal carcinoma and invasive lobular carcinoma. Other less common types of breast cancer include tubular, mucinous, medullary, and papillary carcinomas of the breast.

Infiltrating Ductal Carcinoma

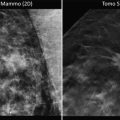

Infiltrating or invasive ductal carcinoma is the most common form of invasive breast cancer, representing 80 % of all invasive breast cancers. Physical examination may reveal a spectrum of findings ranging from a benign exam to a palpable mass, skin thickening or dimpling, nipple inversion, or lymphadenopathy. Mammographically, invasive cancer may present in many ways, such as an increased density, architectural distortion, nodularity, a mass or microcalcifications. Grossly, invasive cancers have a wide range of appearances.

Microscopic features which are examined include tubule formation, nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic activity. Each of the three features is graded from 1 to 3, and a total sum is obtained. A score of 3–5 represents a well differentiated or grade 1 carcinoma. A score of 6–7 represents a moderately differentiated or grade 2 carcinoma. A score of 8–9 represents a poorly differentiated or grade 3 carcinoma. This grading system offers prognostic significance, as patients with grade 1 tumors have significantly better survival than those with grade 2 and grade 3 tumors [11].

Infiltrating Lobular Carcinoma

Infiltrating lobular carcinoma is the second most common histology, accounting for 10 % of invasive breast cancers. At presentation, invasive lobular carcinoma may be multifocal, and the incidence of bilateral synchronous tumors is as high as 20 % in some series [12]. Physical examination frequently reveals very subtle findings such as induration or a fullness of the breast. The mammographic findings of invasive lobular carcinoma may appear as an asymmetric density, architectural distortion or microcalcifications. It is not uncommon to have subtle or vague findings either on physical exam or imaging, often leading to underestimation of the extent of disease.

Histologic analysis characteristically reveals loosely cohesive neoplastic cells invading the breast stroma in single file, a feature referred to as Indian filing. This growth pattern creates linear strands of tumor cells, which likely accounts for the vague, indeterminate findings seen on exam and imaging studies. Lobular carcinoma is characterized by the loss of a cellular adhesion protein known as epithelial cadherin or E-cadherin. This leads to the loose pattern of cells seen histologically. Staining for E-cadherin is performed to differentiate between ductal and lobular carcinomas. Invasive lobular carcinoma will be negative for E-cadherin or down-regulated in 95 % of cases [13–15]. Invasive ductal carcinoma and ductal carcinoma in situ will characteristically stain positive for E-cadherin [16]. Lobular carcinomas typically express estrogen and progesterone receptors (ER/PR), and usually do not express the human epidermal growth factor receptor protein (HER2/neu) [17].

Special Breast Carcinomas

There are several less common types of breast cancer histologies, and these usually have improved prognosis when compared to ductal carcinomas. Among the most common are tubular, cribriform, mucinous, medullary, and papillary carcinomas. Tubular carcinoma usually has limited metastatic potential and excellent prognosis. Pathologic review demonstrates proliferation of glands and tubules in a single layer without a myoepithelial layer. These tumors generally have low nuclear grade, and when associated with in situ disease, the DCIS is also of low nuclear grade [10]. Invasive cribriform carcinoma also has an excellent prognosis. Histologically, a cribriform or fenestrated growth pattern is seen. It is often observed in conjunction with tumors that have tubular patterns as well. The lack of a myoepithelial layer distinguishes invasive cribriform carcinoma from cribriform DCIS [10]. Mucinous or colloid carcinoma is more commonly seen in patients after the sixth decade [18]. On gross examination these tumor specimens are soft, well-circumscribed masses with a gelatinous consistency. Histologically, tumor cells are seen in clusters within pools of extracellular mucin. These tumors have a favorable prognosis. Some studies report 100 % 10-year survival, compared to 60 % for mixed mucinous and infiltrating ductal tumors [18]. Mucinous carcinomas are traditionally ER and PR positive, and HER2/neu negative. Medullary carcinomas often have an aggressive appearance and are often classified as grade 3 tumors [19]. Most commonly it presents as a palpable mass in the upper outer quadrant of the breast, frequently with palpable axillary lymph nodes. On histologic examination, however, the lymph nodes usually reveal benign reactive changes. Medullary carcinomas are tumors which grow in a characteristic syncitial pattern and often have a surrounding moderate lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate [20]. ER and PR status are usually negative or low (0–30 %), and HER2 is generally negative. Despite these poor prognostic indicators, some studies indicate these cancers have a favorable prognosis [19, 21]. Invasive papillary carcinoma comprises less than 1–2 % of all breast cancers, and is more commonly seen in postmenopausal women. Similar to medullary carcinoma, patients can present with palpable axillary lymphadenopathy, but this is commonly due to benign reactive changes [22].

Staging

The staging of invasive breast cancer is based on the TNM classification system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) [23]. The tumor size (T), lymph node status (N), and the presence or absence of distant metastases (M) determines the treatment plan and prognosis of the patient. Stage 1 and 2 tumors are considered early breast cancer, and are usually treated with partial mastectomy followed by whole breast radiation. Axillary lymph node involvement is commonly seen in Stage 3 patients. These cancers are considered locally advanced, and can be considered for neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery. Patients with Stage 4 breast cancer have distant metastases beyond the breast and regional lymph nodes.

Mastectomy

The Halstead radical mastectomy was performed on women with breast cancer for almost 100 years. Removal of the breast, regional lymph nodes, and underlying muscles was the preferred surgical treatment for breast cancer for nearly a decade. This approach was based on the assumption that breast cancers spread in centrifugal fashion, invading adjacent tissue, and then near-by lymph nodes. Complications from the operation were great, and women often suffered from large wounds, lymphedema, and chronic pain. The radical mastectomy underwent numerous modifications as surgeons sought to combine oncologic integrity with less morbid procedures. Patey and Dyson [2] found no difference in overall survival when the pectoralis major muscle was preserved. Madden [24] described preservation of both the pectoralis major and minor muscles, and reported no difference in survival when compared to radical mastectomy. In 1964 Crile [25] recommended excision of the axillary lymph nodes only when they appeared to be grossly involved. In 1991 Toth and Lampert [26] were the first surgeons to describe skin-sparing mastectomy. Preservation of the skin allows for improved reconstruction techniques and better cosmetic result. Retrospective studies comparing skin-sparing mastectomy to standard mastectomy show no difference in recurrence or overall survival [27, 28]. Today, a wide variety of surgical procedures are performed to treat breast cancer. These include total mastectomy with or without reconstruction, modified radical mastectomy, partial mastectomy, sentinel node biopsy, and axillary lymph node dissection.

Total mastectomy is performed for locally advanced breast cancer or diffuse disease. Examples of diffuse disease include muticentric tumors or wide-spread DCIS. Total mastectomy is also performed for inflammatory breast cancer. Women with large tumor to breast ratio may require a mastectomy. A comprehensive review of breast imaging and preoperative image-guided biopsies are essential in all patients with breast cancer [29]. Consultation with a plastic surgeon prior to mastectomy will help determine a patient’s appropriate type of reconstruction. Laboratory work-up should include complete blood count, chemistry, liver function panel, and alkaline phospatase level. Staging work-up is reserved for patients who present as clinical stage 3 or for symptomatic patients whose complaints may indicate systemic metastasis. Staging work-up includes CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, along with bone scan.

If a patient is not an appropriate candidate for reconstruction, total mastectomy is performed by making a large skin ellipse around the nipple-areola complex. A skin-sparing approach is used for patients who are undergoing reconstruction. This incision can be extended medially or laterally to improve exposure during the procedure or allow greater access to the axilla during a dissection. The incision is deepened through the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, and an avascular plane between the overlying skin and underlying gland is identified. Mastectomy flaps can be created with sharp dissection using a scalpel or scissors, or with electrocautery. The plane is followed to the borders of the breast, while attempting to remove all breast parenchyma. The breast is dissected to the anatomic borders of the breast: the sternum medially, the clavicle superiorly, the latissimus muscle laterally, and the inframammary fold or rectus sheath insertion inferiorly. The result is a well-vascularized skin flap. Careful hemostasis is achieved and drains are placed prior to closing the wound. One should try to avoid leaving redundant skin on the chest wall, as a smooth, even surface facilitates wearing of breast prosthesis in a more comfortable fashion. The gland is excised off the chest wall, taking care to include the pectoralis major fascia with the specimen. The breast is handled gently throughout the operation and aggressive manipulation of tissue should be avoided. The specimen is oriented with sutures to help aid pathologic margin analysis. Palpation of the mastectomy flaps should be followed with excision of any additional suspicious tissue.

Recently, surgeons have embarked on nipple-sparing mastectomy and nipple and areola-sparing mastectomy. When performing these procedures, intraoperative analysis of the ductal tissue in the nipple can be performed. There are several methods to achieving this goal. One method involves gently inverting the nipple by the surgeon’s forefinger and the ductal tissue is then sharply dissected from the skin. Another method is to sharply dissect the plane deep to the nipple and evaluate this tissue intraoperatively. Some surgeons will place a marker on the nipple bed for orientation purposes for the pathologist. Simmons and colleagues [30] reported on a series of nipple- and areola-sparing mastectomies. In their series, they found a nipple involvement rate of 10 %. Laronga et al. [31] reported a 3 % nipple involvement rate. If intraoperative analysis of the ductal tissue in the nipple is performed and the tissue is found to contain a malignancy, subsequent resection of the nipple-areola complex (NAC) is mandatory. In a retrospective study evaluating 353 nipple-sparing mastectomies, the NAC was preserved in 96.7 % of cases performed [32]. Few patients will retain sensation of the nipple, and both partial and complete nipple loss can be seen. Sacchini [33] published a review of 192 nipple-sparing procedures with a median of 24.6 month follow-up. No patients had involvement of the NAC on pathologic review. Nipple loss in this series was 11 %. Two patients had a local recurrence, but neither recurrence was in the NAC. Careful patient selection remains the key aspect in performing these operations.

Breast Conserving Surgery

In the 1970’s increasing use of mammography led to the detection of smaller tumors in the breast, and women were therefore diagnosed at an earlier stage. Surgeons sought to perform less radical surgery and explored the possibility of offering partial mastectomy as an appropriate treatment for breast cancer. Numerous studies were designed to validate the role of breast conserving surgery (BCS). Today, breast conserving surgery is performed for early stage breast cancer. As previously mentioned, the two landmark trails which established partial mastectomy as a treatment for early stage breast cancer were published by Fisher [7] and Veronesi [9]. Fisher and colleagues conducted the NSABP B-06 trail from 1976 to 1984. This phase III trial enrolled 1,600 women with tumors 4 cm or less, and randomized them into three treatment arms. The three arms compared were modified radical mastectomy, partial mastectomy with axillary dissection, and partial mastectomy with axillary dissection and whole breast radiation. Twenty-year follow-up showed higher rate of locoregional recurrence in the group who underwent partial mastectomy with radiation compared to the group who underwent a modified radical mastectomy [8]. However, equivalent disease-free and overall survival was seen in these two groups. Veronesi [9] compared radical mastectomy to quadrantectomy with axillary dissection and radiation. In this study, 701 women with tumors 2 cm or less were randomized. Local recurrence in the radical mastectomy arm was 2.3 %, compared to 8.8 % local recurrence in the quadrantectomy arm. However, 20-year follow-up showed no difference in distant metastasis or overall survival in the two groups. These two pivotal studies helped establish breast conserving surgery as an acceptable and oncologically sound operation for the treatment for early stage breast cancer. It also provided clear evidence for the essential role of radiation in breast conserving procedures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree