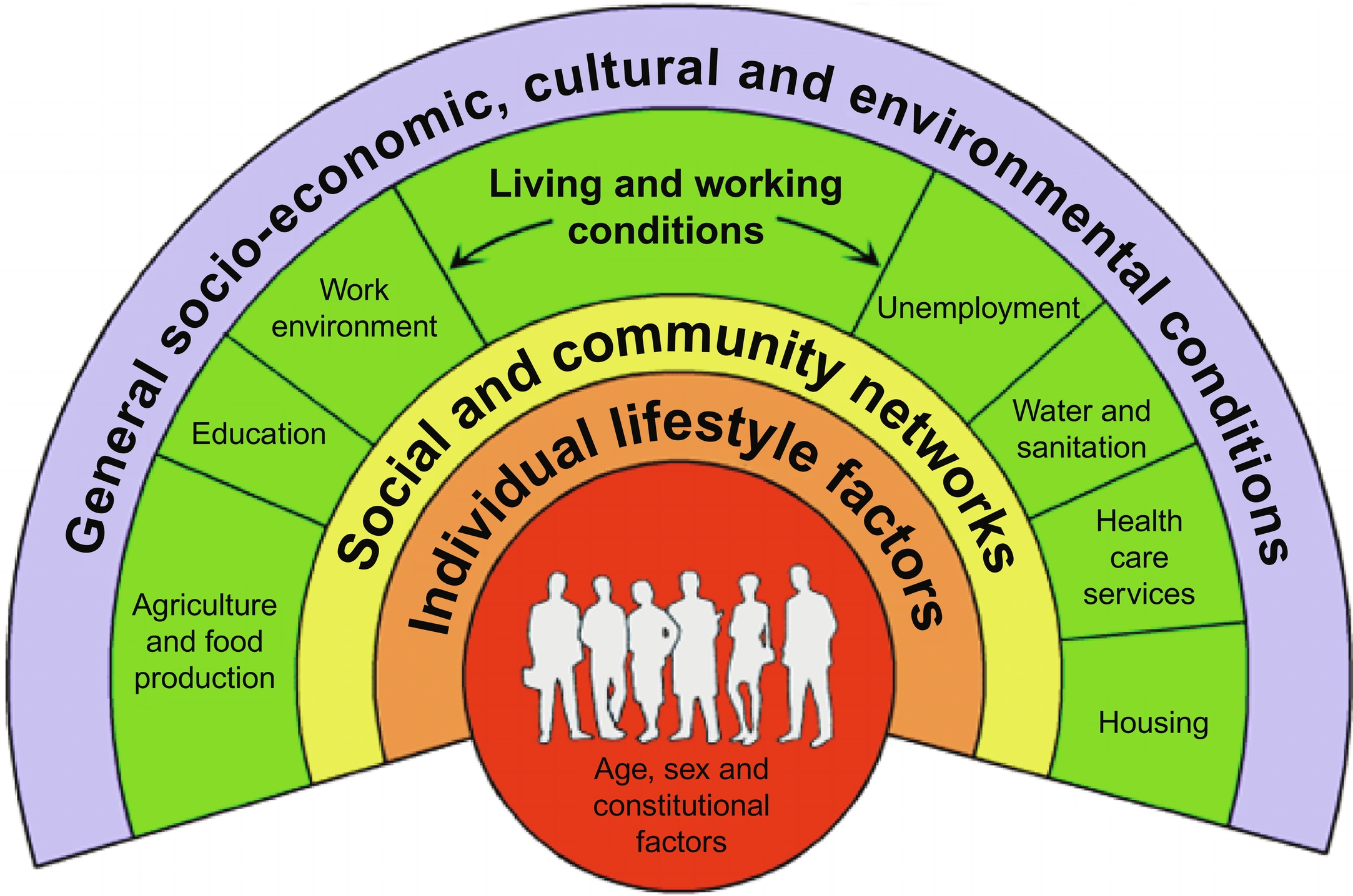

It is well-documented that “…the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age…” can negatively, or positively, influence our health. With few exceptions, an inverse association is reported between social advantage and chronic disease : this has been also observed across the lifecourse whereby childhood exposures negatively influence health outcomes in later life . One of the earlier, now superseded, models to introduce the notion of how social factors and structures at the micro, meso, and macro levels influence health was posited by Dahlgren and Whitehead; known colloquially as the “rainbow model” ( Fig. 1 ). Subsequent models acknowledge multidirectional influences of social determinants, and the role of accumulated disadvantage over the lifecourse. Some are even inclusive of financial and social support on which one can draw in times of need, health policy, “norms,” health literacy, and access to quality and/or preventive healthcare. What is consistent across the models is the imperative role of social and environmental factors in determining risk for chronic disease , indeed a large range of evidence suggests that the lifestyle-related risk factors for musculoskeletal conditions, and the conditions themselves, are no exception to this paradigm .

Socially patterned risk factors for osteosarcopenia

The evidence of crosstalk between muscle and bone is increasing , in addition to evidence regarding muscle and bone being interconnected biochemically . Furthermore, lifestyle-related factors that influence one tissue are likely to also influence the other. Not only are there many commonalities in lifestyle risk factors for sarcopenia and osteoporosis, and thus osteosarcopenia, these factors are also influenced by social determinants. For sarcopenia, three of the key modifiable risk factors are sedentary lifestyles, inadequate dietary protein intake, and vitamin D deficiency . For osteoporosis, common modifiable risk factors are low body weight, alcohol intake of ≥ 30 g/day, current smoking, low dietary calcium intake, low serum vitamin D, and a range of chronic conditions . The majority of these modifiable risk factors for osteoporosis and sarcopenia (and thus osteosarcopenia) all relate to economic and geographical access, and indeed affordable, available and accessible opportunities for education, housing, access to fresh foods, and social security policies, among many other social determinants. Other modifiable risk factors for osteosarcopenia include smoking and alcohol consumption, for which the association with education and income have been well-documented .

Childhood precursors to osteosarcopenia in later life?

Environmental factors and the interplay between social and biological factors during childhood are integral to the musculoskeletal system. These may not only dictate risk for osteosarcopenia in later life, but the accumulation of disadvantages over the lifecourse may increase the trajectory of bone and muscle loss. Here, we discuss the biological plausibility for such a suggestion, taking a focus on physical activity and dietary calcium intake.

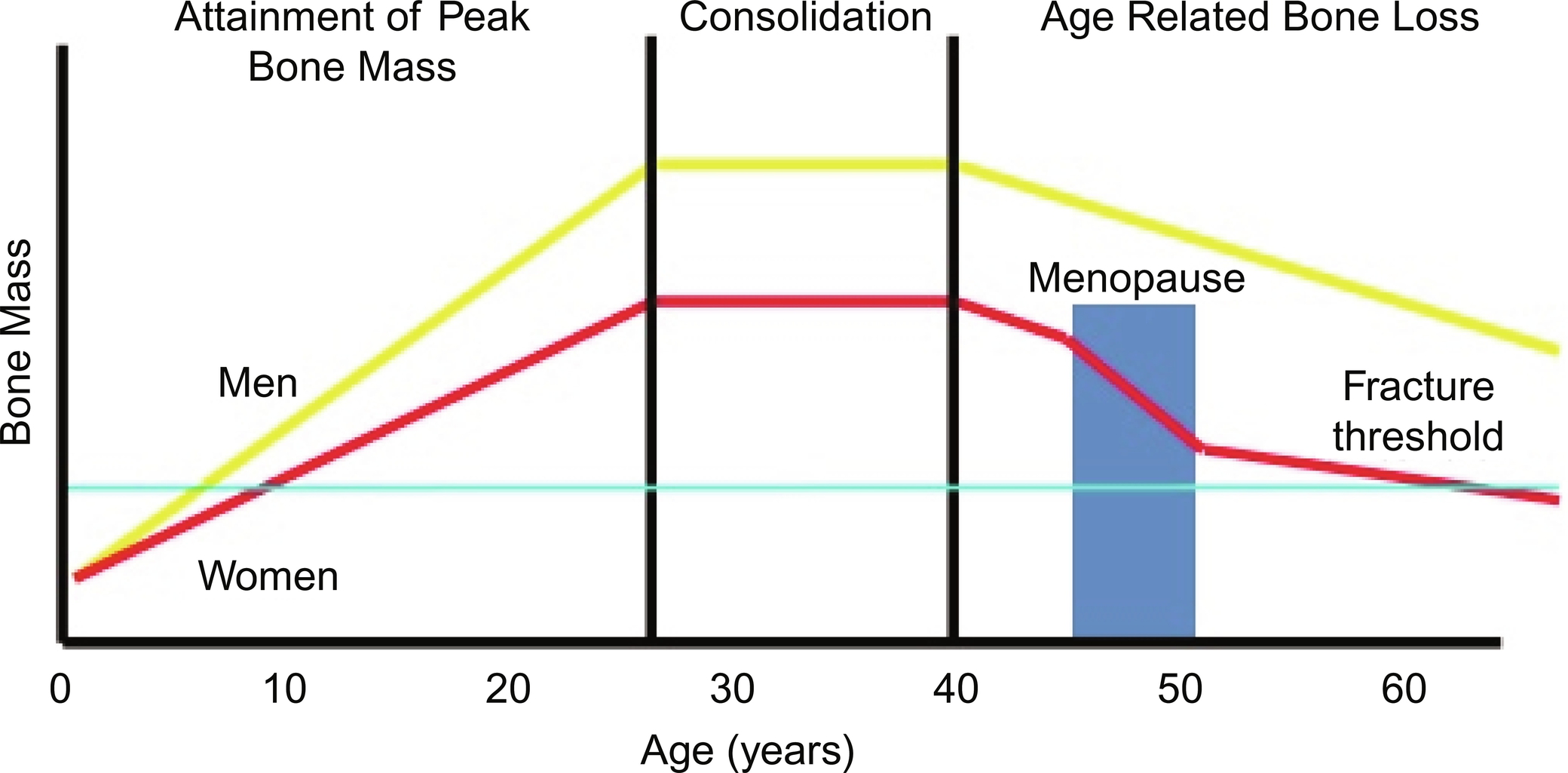

The accrual of bone mass begins in utero and continues until reaching peak bone mass around the third decade of life ( Fig. 2 ). After a consolidation period, age-related bone loss involves a gradual and progressive decline which is a result of a predominance of bone resorption over the bone formation . Although a significant reduction in bone formation is associated with increasing age for both sexes , a steeper decline in bone loss is observed for women compared to men : a factor primarily associated with low levels of estrogens across the menopausal years ( Fig. 2 ). Interestingly, muscle mass also begins to decline with advancing age, with a decline of between 1% and 2% being observed every year after the age of 40 years , and an acceleration of this loss after the age of 65 years.

Bone

In a study of 729 participants in the Midlife in the United States Biomarker project, both childhood socioeconomic advantage and adult educational attainment, but not adult financial status, were associated with higher adult lumbar spine bone mineral density . Another study from the same cohort investigated childhood social adversity and bone strength in adults, including the ability of the femoral neck to withstand axial compressive loading (compression strength index), the ability to withstand bending (bending strength index), and the ability to absorb the energy of an impact associated with a fall from standing height (impact strength index) . The authors of that study reported that for every standard deviation (SD) increment of childhood advantage score, femoral neck indices increased by between 0.18 SD and 0.26 SD: those associations remained unchanged after adjustment for adult socioeconomic status . Interestingly, only bending strength remained significant after adjustment was made for lifestyle behaviors . Those data suggest an influential role in childhood social circumstances in bone acquisition. Furthermore, it is important to note that in older, community-dwelling women, each SD increment in femoral neck strength indices is associated with 57%–66% relative reduction in hip fracture risk over 10 years . Given this, if strength indices had comparable fracture risk associations in older white men, we would expect 36% lower hip fracture risk in those with an advantaged childhood compared to those with the most disadvantaged childhood .

Muscle

Global estimates suggest that young people and older adults are among the most sedentary groups spending ~ 60% of their waking hours engaged in sedentary behaviors . While it is well established that sedentary behavior increases the risk of pediatric obesity , and potentially results in early-onset cardio-metabolic diseases such as type II diabetes and cardiovascular disease , there is less consensus, however, about the potential detrimental impacts childhood, sedentary behavior may have on the musculoskeletal system, despite biological plausibility. Too much time spent sedentary, such as during extreme bed rest, can negatively affect muscle health and indeed increase muscle wasting . Data suggest that increased sedentary behavior may result in skeletal muscle fiber replacement by noncontractile (fat) components potentially resulting in a deterioration of muscle quality from a younger age, which may be linked to muscle weakness and poor muscle function across the lifecourse . In growing girls (age 9–12 years), Farr et al. showed a negative association between low physical activity and skeletal muscle, fat, bone density, and strength parameters. Furthermore, that study showed low levels of physical activity were associated with lower muscle density . Combined, these data suggest that reduced muscle density and lower physical activity may put children at risk of suboptimal skeletal loading. It is plausible that these findings may be heightened in children and adolescents with long-term sedentary behavior, resulting in a greater associated risk for early-onset osteosarcopenia later in life. However, in healthy growing children whether long-term sedentary behavior acts to undermine these effects of physical activity in a similar way remains unclear. Data hints at this issue, however, as in a study of 1403 UK-based men and women, low birth weight at birth and 1 year was significantly associated with poor adult grip strength even after adjustment for adult size .

Synergistic role of bone and muscle

To argue for biological plausibility, we highlight that muscle and bone both adapt mass and strength in response to mechanical load . Therefore, mechanical loading, particularly in early life, plays essential role in the health of bone and muscle development . Currently, there exists a paucity of data regarding the simultaneous contribution of muscle mass and strength to bone health during childhood. However, observational studies are suggestive of an indirect pathway between muscle power and bone strength . It is plausible that these findings may be heightened in children and adolescents with long-term sedentary behavior, resulting in a greater associated risk for early-onset osteosarcopenia later in life.

Contemporary studies of children show unprecedented higher proportions of inactive and obese Australian children and adolescents. These measures of disproportionately increasing body habitus in children will have much potential to negatively influence the accrual of bone and muscle, plausibly increasing the risk of early-onset osteosarcopenia later in life.

Both muscle contraction and gravitational loading must be of sufficient magnitude and rate, and be sufficiently dynamic and multidirectional in their application, to provide the necessary stimuli to drive bone adaptation during growth . This optimal loading stimulus may not be obtained in children who are spending a large proportion of their time in sedentary activities.

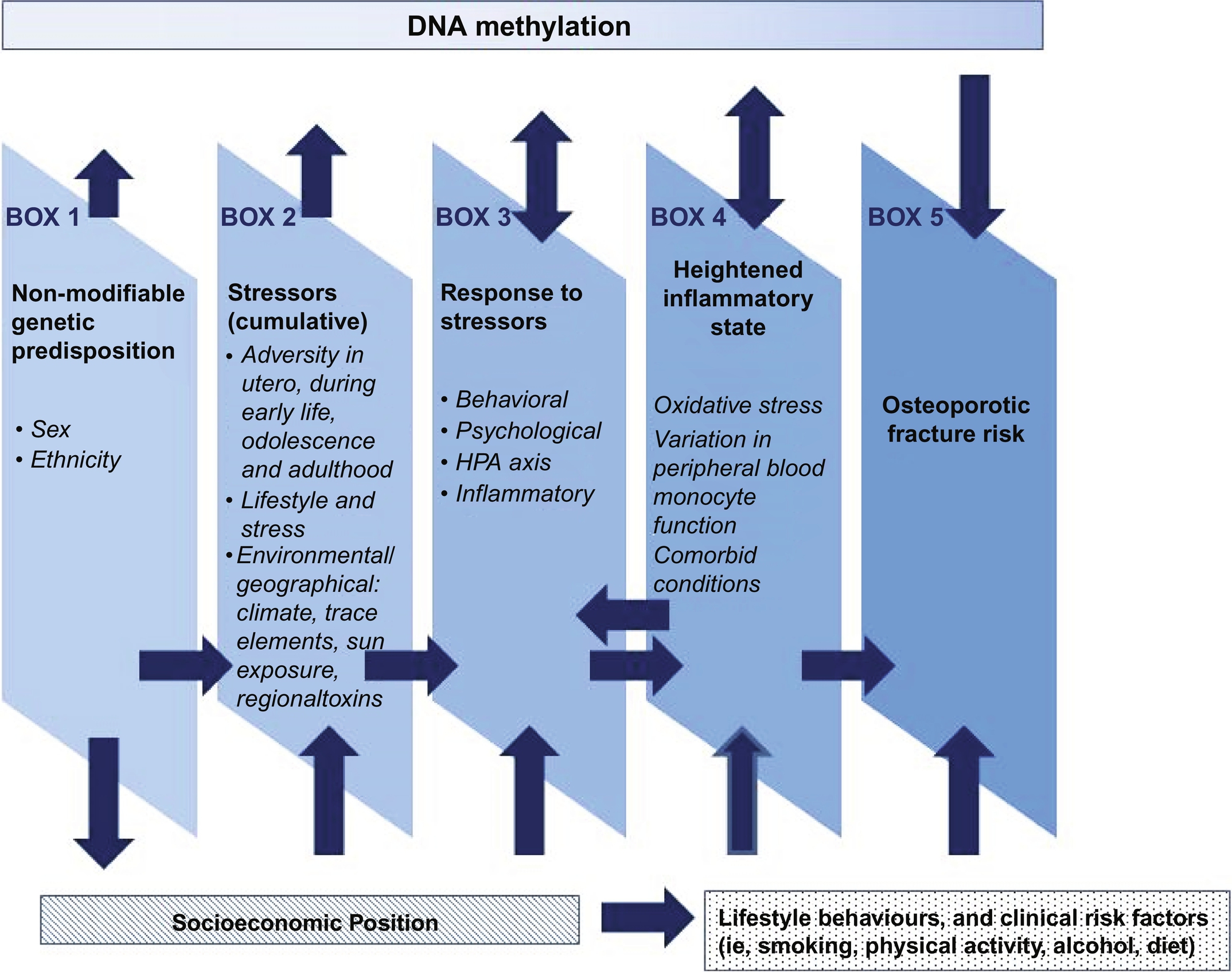

Conceptual model: The social-biological nexus

Based on a large evidence-base of research in the field of social disadvantage and osteoporosis , we have posited that socially patterned risk factors impact osteoporosis risk across the lifecourse, thus influencing the likelihood of osteoporotic fracture . Here, we argue that the conceptual model for osteoporosis (Fig. 3) could be refocused to encompass the geriatric condition of osteosarcopenia. Indeed, it is not just the direct biological effect of risk factors, but the biological mechanisms at different life-stages , and what that may mean for the onset of osteosarcopenia.

In utero

While poor bone health is more commonly the domain of gerontologists, it has been postulated that osteoporosis is, in fact, a “pediatric disease with geriatric consequences” . The “Barker hypothesis,” which was initially about coronary heart disease, suggested that “…adverse environmental influences in utero and during infancy, associated with poor living standards, directly increased susceptibility to the disease” . From this came the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) theory, which suggested biological “programming” occurring in utero. Combined, the environmental, nutritional, and genetic influences in utero have the potential for long-term impact upon a broad range of offspring health outcomes : given this has been argued for osteoporosis and sarcopenia , we must consider plausibility for including osteosarcopenia in this argument.

Various maternal conditions influence conditions in utero; the most common include stress, nutrition, and vitamin D . These conditions can alter metabolism, influence placental calcium transporters, influence alterations to neuroendocrine-immune network set-points, upregulate immune function and inflammatory responses (via the HPA axis and/or sympathetic nervous system), increase the expression of glucocorticoid receptors, influence the methylation of the RXRA promoter, and alter the eNOS promoter . In human growth muscle development first occurs in the formation of fibers approximately 6 weeks gestation . The development of primary muscle fibers is controlled by genetic influences, whereas the development of secondary fibers (during week 8 and 21 gestations) are more sensitive to maternal and prenatal environmental factors such as nutrition and hormonal release . That environmental sensitivity extends further into the postnatal period . This notion can further be supported through the relationship of birth weight and adult grip strength suggesting the prenatal and postnatal period may have long-term importance for muscle function. The reports that the relationship of birth weight and grip strength remains following adjustment for adult size further supports the influence of early life on later muscle function. Although the mechanism remains unknown it is postulated that it reflects altered fiber type, proportion, and quality which may have consequences not only on the attenuation of peak muscle but also on the subsequent muscle decline .

Early childhood

It is argued that genetics and environment both significantly impact growth ; however, there are periods across the lifecourse in which one or the other factor appears dominant. For instance, at birth, we obtain a particular genetic blueprint that indicates our specific potential for growth and development without the influence of our environment . However, our ability to meet that potential is often influenced by our environment, particularly during the first 1000 days of life . Importantly, the timing, duration, frequency, and strength at which these environmental triggers occur in addition to the age and gender of the child will impact our potential to develop . The primary control mechanism affected by environmental insults is the endocrine system (responsible not only for the control of specific hormones but also for complex associations with key tissue responses). It is important to note, that at some point in our life we will all experience environmental insult . This is evident right from intrauterine in which growth would have been restrained by the size of our mother’s uterus. Similarly, during childhood, many would have experienced childhood illness or disease negatively impacting growth and in particular that of bone and muscle tissue. These naturally occurring insults have previously been likened by Waddington to the movement of a boulder rolling down the groove of a valley : whereby, if an insult occurs, the boulder is pushed out of its groove and forced up onto the walls of the valley. The magnitude of the deviation from the natural pathway will depend on the timing, duration, and strength of the insult. A greater more severe insult will result in greater long-lasting effects on growth and thus an associated affected to the development of bone and muscle .

A specific example during infancy and childhood is that in which environment insult results in the increased secretion of stress hormones and altered levels of cortisol, altering the HPA axis response, increasing proinflammatory cytokines, and heightening the inflammatory response resulting in differences in gene expression patterns . A link between chronic stress and impaired bone growth and development in children has been documented . The growth plate is targeted by stress through different mechanisms, including increased serum concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines and cortisol . The impaired actions of the growth hormone-insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) axis have direct effects on the growth plate and disrupt growth plate vasculature . Proinflammatory cytokines and cortisol adversely affect several aspects of chondrogenesis in the growth plate . Indeed, high levels of stress experienced in early life may reset the neurological and hormonal systems, thus permanently affecting children’s epigenetic processes and phenotypic expression of disease risk .

Lower health literacy

We argue that there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that the relationship between social disadvantage and poorer bone health may be, in part, mediated by health literacy . Health literacy is a multidimensional concept that encapsulates the capacity to access, understand, appraise, and apply health information to make decisions about health care, disease prevention, and health promotion . Lower health literacy is a concern in both developed and developing countries including Australia and Europe where up to 60% of the population has less than adequate health literacy . Health literacy is strongly associated with adverse health outcomes including a higher prevalence of chronic conditions, increased risk of mortality, delayed treatment, and increased hospitalizations .

Health literacy and risk factors

Suboptimal health literacy is most common in older populations, and those with a lived experience of social disadvantage . Low health literacy is also associated with a higher prevalence of some risk factors for osteosarcopenia including nutrition, smoking, physical inactivity, and vitamin D knowledge , and has been associated with prefrailty and frailty . Finally, risk factors for osteosarcopenia are greater among groups with lower socioeconomic status . The combination of low health literacy and social disadvantage will thus disproportionately increase the likelihood that risk factors for osteosarcopenia are present.

Health literacy and prevention and treatment

Use of health services

Health care systems are increasingly difficult to navigate and evidence strongly indicates that low health literacy contributes to adverse health outcomes in these systems , including delayed care or access to providers . Among older people, particularly those from CALD backgrounds there are difficulties accessing transport to health services, long waiting times for appointments, gender sensitivity, and feelings of shame when receiving care from a nonfamily member . Socioeconomic disadvantage is also shown to be associated with increased length of hospital stay, fewer visits to specialists, and shorter waiting times . For culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) populations, access and uptake of services are also limited . People with disabilities, particularly intellectual or developmental disabilities, are also subjected to health service exclusion as they age .

Ability to self-manage

Inadequate health literacy may also limit a person’s ability to participate in decision‐making, follow self-care recommendations, and implement self-management behaviors . This is also the case for older adults, although one study identified that simple self-management tasks such as taking medication were achievable in adults aged over 75 years, even among those with lower health literacy . Low health literacy may also be a risk factor for the physical decline in older adults , thus further impacting their ability to self-manage.

Adherence to treatment recommendations

The ability to adhere to treatment recommendations is compromised by age-related changes in health literacy, which may be partly explained by cognitive ability . Mild cognitive impairment is associated with lower health literacy, with a stronger association seen in those with lower education . Low health literacy and declining cognitive functioning may thus be barriers to adherence to treatment recommendations, more so among lower socioeconomic groups .

The combination of multimorbidity and lower health literacy also increase difficulty in adhering to treatment regimes. Multimorbid patients often have a high treatment burden and poorer quality of life and this has been associated with lower levels of health literacy in several studies . Mechanisms may include difficulties with understanding and applying complex health information and instructions , particularly in relation to polypharmacy . Limited affordability related to multimorbidity and associated high health care use may also be an issue for older people .

Given that low health literacy may be likely to contribute to premature bone deterioration, and thus disability and dependency with subsequent greater reliance on acute care, this prompts a shift toward addressing disparities in health outcomes by ensuring the delivery of health information and services in ways that address health literacy needs , particularly of older adults.

Social impact of osteosarcopenia

Quality of life

Older adults with osteosarcopenia are at higher risk of falls, fractures, and entry into a nursing home, thus exacerbating the trajectory of poorer quality of life . Data shows that quality of life and health utility reduce significantly with the number of fractures experienced . In older women aged 65 years and over, data suggest a greater likelihood of depression after experiencing a fracture compared to their counterparts of the same age that had not experienced a fracture . For sarcopenia, a systematic review and metaanalyses reported an independently associated almost twofold increased likelihood of reporting depression ; while these findings were based on the observational studies alone, and thus causality cannot be determined, such a relationship is plausible due to the significant loss of muscle strength and functionality that accompanies sarcopenia . The reduced aspirations of/and attainment of quality of life that accompanies depression, therefore, indicate the imperative of considering depression for those with osteosarcopenia.

Identity

Identity for older people bears a close relationship to concepts such as independence, autonomy, and a sense of belonging . A person’s self-concept is likely to play a significant role in their experience of osteosarcopenia; identity can be profoundly affected by physical and psychosocial consequences of osteosarcopenia, yet can also act as a powerful mechanism for coping and thriving with the condition . Older community-dwelling adults recovering from recent hip fracture surgery have described the importance of identity factors (including their dignity and independence, the ability to express personality traits, such as creativity, persistence, and positivity, and being reunited with familiar rituals and environments), as key facilitators in their self-confidence and overall recovery. Data from a qualitative study of men (age range 52″86 years) suggests that some men still consider osteoporosis, and thus plausibly osteosarcopenia, as being a “woman’s” disease’ . Consider the impact of medical terminology on identity and empowerment: Taylor reveals the concept of “frailty” as a double-edged sword for older people, on the one hand soliciting care and support for elders, yet at the same time risking the dignity and empowerment of this already marginalized population. Indeed, very recent qualitative data suggest that older adults’ perspectives on the concept of frailty are highly negative-some have indicated that frailty is perceived as an unmodifiable state strongly associated with fragility, lowered self-worth, loss of control, and the end of life . Further, being labeled as frail has been associated with “…a loss of interest in participating in social and physical activities, poor physical health and increased stigmatisation” for older adults . Given this, and the self-reported value for older people with osteoporosis in identifying as “capable” and “resilient” , we might consider whether applying a label of “frail” to all older patients with musculoskeletal decline maybe, in fact, counterproductive .

Older people reported actively resist accepting a medical determination of frailty by using a range of strategies including maintaining meaningful task regimes (e.g., gardening, cooking, etc.), positively comparing their own situation to others’, and compartmentalizing health conditions to avoid acknowledging an overall state of illness or physical weakness. Particularly for men, qualitative data has suggested that older men may apply more importance to the physical functionality of their body-a construct of masculinity-than women of the same generation . Yet, despite drawing on their identity as a source of strength, older fracture survivors have also described experiences of fracture and vulnerability in the face of lost capabilities, or from their increased dependency and perceived burden on others .

People diagnosed with osteosarcopenia or its constituent conditions can struggle to accept their new diagnosis as part of their identity, especially when the conditions are not visibly manifest . From a systematic review of qualitative studies concerning the lived experience of osteoporosis , it is observed that a lack of noticeable symptoms at the time of diagnosis can obscure patients’ appreciation of fracture risk or disease severity. Without perceptible evidence to the contrary, people with low bone density may continue to identify as strong and at low-risk, or may see themselves as being the wrong “type” of person to develop osteoporosis . Conversely, others may become unnecessarily anxious or risk-averse based on the medical or media hyperbole . Meanwhile, the presence of visible or apparent disease markers (such as pain, fracture loss of height, or spinal deformity) often results in compromised biographical integrity, where once-healthy identities are threatened by struggles with isolation, vulnerability, and dependence on others . Older adults with chronic physical conditions including osteoporosis report struggling with the appearance and increasing unreliability of their bodies, at times expressing feelings of shame, embarrassment, and reduced self-worth . Regression analyses have similarly confirmed an association between frail/prefrail status and low self-esteem . Traumatic events such as a fracture can result in a rapid and radical disruption to personal identity , leaving older fracture survivors especially vulnerable. Coping with a diagnosis is further complicated by ambiguous medical advice and media reporting around fracture risk, prognosis, and treatment options . At the same time, some older people with osteoporosis or hip fracture seem to have accepted physical suffering and functional restrictions as a reality of “becoming old,” and have described a gradual and successful adaptation to a new way of life, achieved through the use of adaptive aids, new supports, or the vicarious enjoyment of inaccessible activities.

Osteoporosis is often positioned as a “female disease” and qualitative studies have reported descriptives such as “… the crumbly status of old age” (p. 32). These framings of osteoporosis can give rise to additional identity conflict for men and individuals who did not previously view themselves as elderly or frail . There is also some evidence of the influence of belief systems and cultural variation in the way that osteoporosis is conceptualized and managed , which can, and perhaps should be, extrapolated to understanding osteosarcopenia. For example, “ageism” is a notion that refers to the stereotyped and discriminatory view of older persons based on their age; importantly, it is a contemporary paradigm of the Western world , and, while taking care not to apply a different stereotype to Asian-Pacific cultures, there exists an obvious east-west variation in filial piety. Negative stereotypes of older persons differ between countries and indeed between lower income vs moderate-higher income countries, thus indicative of not sharing a “western” value regarding advancing age , nor the potential for independence continuing through older age. Aligned with this issue is that aged care homes are predominantly a western phenomenon . Although sarcopenia is still a relatively new disease and thus has little awareness in the public domain and is suboptimal in the clinical domain, it too is likely to develop these associations and corresponding identity challenges in time.

Social exclusion

Loneliness and social isolation among older adults can lead to adverse mental and physical health outcomes including frailty and increased risk of nursing home admission . In turn, poor health and limited mobility can lead to social exclusion , further exacerbating the risk of social isolation. There is also evidence that the combination of social isolation, loneliness, and low socioeconomic status significantly increases the risk of poor health behaviors . Both loneliness and social isolation are more prevalent among older adults with lower health literacy . This may be due to less effective communication skills among older adults with low health literacy, limiting their ability to maintain a large social network . Also, social isolation has been reported to increase the more times a fracture occurs . Social participation has, however, been observed to facilitate both the maintenance of functional skills and recovery from serious fractures . Older adults with osteoporosis or recent fracture report physical environments to be a major participation barrier ; it, therefore, follows that the provision of safe, accessible, and dignified transport and other spaces may enhance participation and wellbeing outcomes for older populations including those with osteosarcopenia. Additionally, older individuals whose social isolation is compounded by cognitive or communication disability should be referred for speech-language pathology or other allied health support, to ensure better participation in healthcare decision-making and wellbeing outcomes.

Entry into a nursing home

Having osteosarcopenia significantly increases the risk of entry into a nursing home . As discussed earlier, while data are sparse it is likely that osteosarcopenia risk is associated with lower health literacy, and the condition itself has been well-documented as associated with poorer quality of life, we argue that older adults with osteosarcopenia are disproportionately disadvantaged. Considering the combination of lower health literacy, poor quality of life, having a little-understood geriatric condition, an increased risk of entry into an aged care facility, and an attributable increased risk of depression and lowered self-esteem or self-worth, it is vital in the clinical and research domains to consider the social context of osteosarcopenia. In terms of entry into an aged care facility, given this is determined by access to financial resources, the choice of a nursing home may be limited. Also, once residing in an aged care facility, personal visits may be fewer from their social circle and/or family. In one study, up to 40% of the nursing home, residents reported being lonely, with family relationships and level of mobility determining the degree of the loneliness felt by residents . Nursing home residents report that this lack of meaningful relationships, in turn, leads to more loneliness and loss of self-determination , introducing a downward spiral toward a loss of purpose for living.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we posited a conceptual lifecourse model: the utility of which includes targeting those most at risk of developing osteosarcopenia by addressing causative environmental pathways that are greater for socially disadvantaged persons. We suggest that if we are to positively influence the process of healthy aging and reduce the plausibility for inequitable disparities in osteosarcopenia risk seen across social groups, we may need to focus on younger ages and address the modifiable lifestyle factors that are socially patterned. In older adults, clinical attention could be focused on identifying those most-at-risk and affording extra time to ensure effective health communications, thus ameliorating the negative effect of low health literacy on the likelihood of this condition. Although there exists a plethora of community-based health promotion programs that encompass an array of lifestyle modification options to enhance bone and muscle health, national health-related and multisectoral policies and strategies must prioritize health inequities and overall inclusion for this population .

References

1. World Health Organization : https://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/

2. Marmot M.: Achieving health equity; from root causes to fair outcomes. Lancet 2007; 370: pp. 1153-1163.

3. Marmot M.: Addressing the causes of the causes. Lancet 2018; 391: pp. 186-188.

4. Barker D.: The origins of the developmental origins theory. J Intern Med 2007; 261: pp. 421-427.

5. Barker D.: Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ 1995; 311: pp. 171-174.

6. Gluckman P.D., Hanson M.A., Cooper C., Thornburg K.L.: Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: pp. 61-73.

7. Dahlgren G., Whitehead M.: Policies and strategies to promote social equity and health.1992.World Health OrganisationCopenhagen

8. Brennan S.L., Holloway K.L., Williams L.J., Kotowica M.A., Bucki-Smith G., Moloney D.J.: The social gradient of fractures at any skeletal site in men and women: data from the Geelong osteoporosis study fracture grid. Osteoporos Int 2015; 26: pp. 1351-1359.

9. Brennan S.L., Yan L., Lix L.M., Morin S.N., Majumdar S.R., Leslie W.D.: Sex and age-specific associaitons between income and incident major osteoporotic fracgtures in Canadian men and women: a population-based analysis. Osteoporos Int 2015; 26: pp. 59-65.

10. Brennan S.L., Leslie W.D., Lix L.M.: Associations between adverse social position and bone mineral density in women aged 50 years or older: data from the Manitoba Bone Density Program. Osteoporos Int 2013; 24: pp. 2405-2412.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree