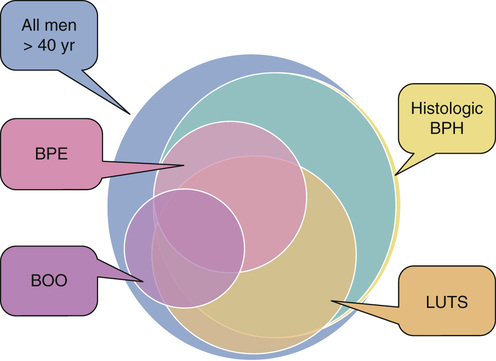

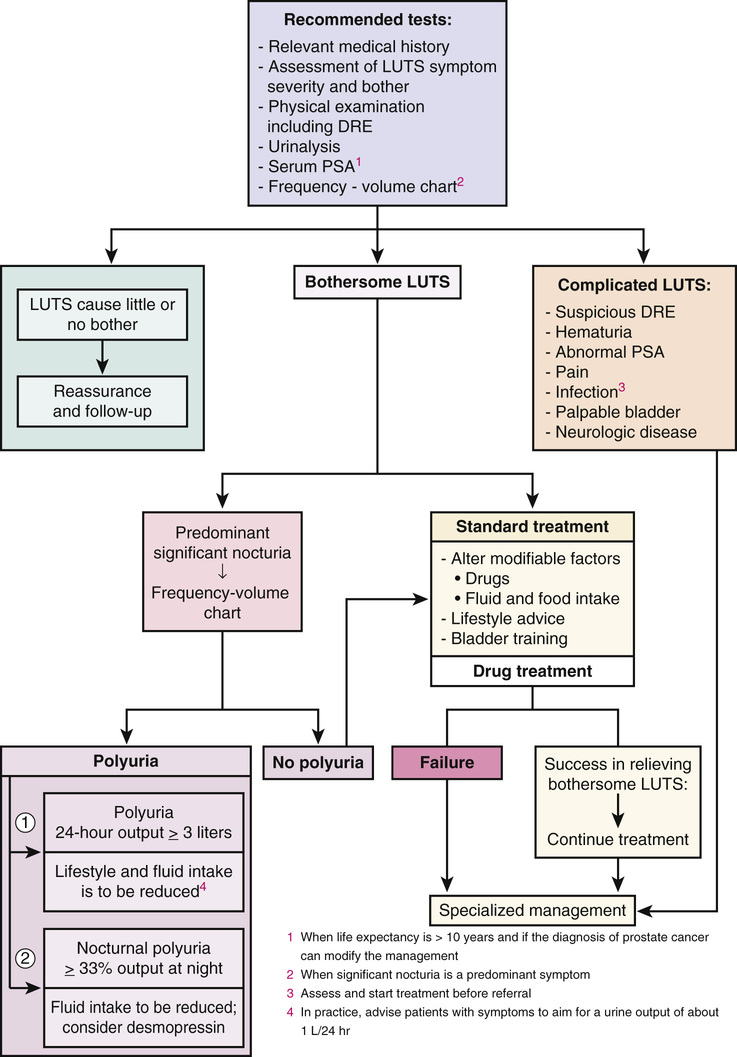

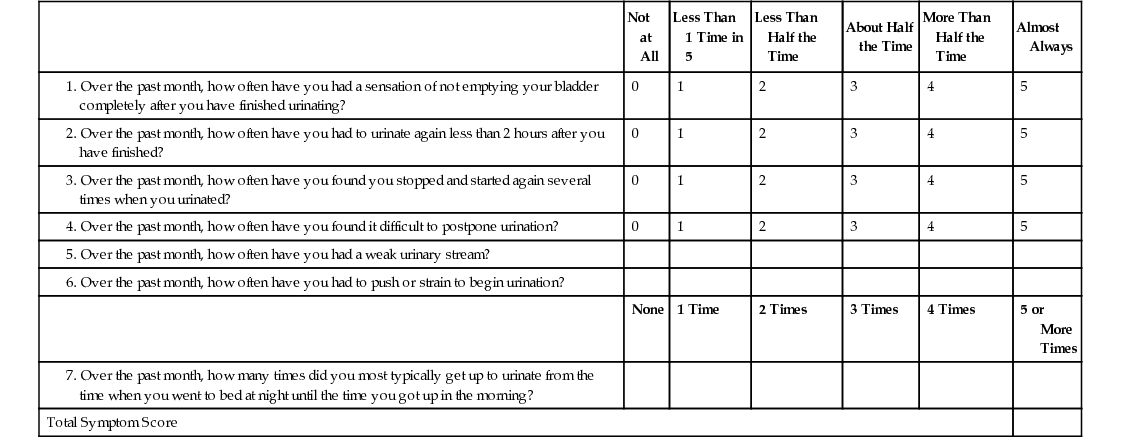

William Cross, Stephen Prescott Prostate gland disorders are extremely common and a frequent reason for medical consultation in older men. The two most prevalent prostate conditions are benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostate cancer, both of which increase in incidence with advancing age. Benign prostatic enlargement (BPE) is the fourth most common diagnosed condition, following coronary artery disease/hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes, in men older than 65 years.1 In 2000 in the United States, approximately 4.5 million visits were made to physician offices for a primary diagnosis of BPH, and the estimated direct cost of BPH treatment was $1.1 billion exclusive of outpatient pharmaceuticals.2 Prostate cancer is the second most frequent cancer diagnosed in American men, with 6 cases in 10 diagnosed in those aged 65 years or older. The estimated cost of prostate cancer care in the United States in 2010 was $11.85 billion (total cost of cancer care $124.57 billion), which is projected to increase to approximately $19 billion by 2020.3 As the aging population increases and prostate disorders become more prevalent, the majority of men with prostate conditions will increasingly rely on medical care being delivered by health care professionals other than urologists. It is important that these health care providers are aware of the latest prostate guidelines and care pathways in order to deliver the highest quality of care, improve clinical outcomes, and contain health care costs. BPH is a pathologic process that, by definition, can be diagnosed only by histologic assessment and not by physical examination. Historically, many men with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) were labeled as having the symptom complex of “prostatism,” which was almost universally attributed to BPH. This clinical assumption has been challenged with the appreciation that male LUTS may be unrelated to the prostate gland and secondary to other pathology or even a side effect of medication (Box 83-1). This greater understanding of the pathophysiology of male LUTS has contributed to an evolution of the clinical terminology, which now offers a more descriptive assessment of the presenting symptoms4 (Table 83-1). Therefore, although many men present with LUTS suggestive of bladder outflow obstruction (BOO), and on clinical examination have BPE secondary to BPH, it is not uncommon for a man to have significant LUTS without BOO, BPE, or BPH (Figure 83-1). This highlights that the selection of appropriate treatment for male LUTS requires a careful evaluation of symptoms to identify the underlying causative condition(s). TABLE 83-1 International Continence Society Definitions of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms LUTS are highly prevalent in the male population. The Multinational Survey of the Aging Male (MSAM-7) questioned nearly 13,000 men aged 50 to 80 years in the United States and six European countries.5 Overall, 31% of respondents reported moderate-to-severe LUTS, which was consistent across the countries. The prevalence was positively related to age, ranging from 22% in men aged 50 to 59 years to 45.3% in men aged 70 to 80 years. One interesting finding is that only 19% of men with LUTS had sought medical help for their urinary symptoms and only 10.2% had been medically treated. The Rancho Bernardo Study, a prospective, community-based study of aging, assessed the prevalence and characteristics of LUTS in community-dwelling men aged 80 years and older.6 The prevalence of LUTS was 70% in men 80 years and older and 56% in men younger than 80 years (P = .03). Compared to the younger men, those aged 80 years or older also reported more severe symptoms. The prevalence of BPH, similar to that of LUTS, also increases with age. It is important to note that when interpreting and comparing the literature on the prevalence of BPH, caution is needed because epidemiologic studies have used both histologic and clinical definitions to calculate the prevalence. Autopsy studies have revealed that based on histologic criteria, BPH increases from 8% in men aged 31 to 40 years, to 40% to 50% in men aged 51 to 60 years, and over 80% in men older than 80 years.7 The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging compared the age-specific cumulative prevalence of male LUTS with the autopsy prevalence of BPH and reported a close correlation.8 The incidence and prevalence of BPH and LUTS are increasing significantly as the U.S. population ages. Between 1998 and 2007, the age-adjusted prevalence of BPH among hospitalized patients in the United States nearly doubled.9 BPH is histologically characterized by an increase in epithelial and stromal cells in the region adjacent to the prostatic urethra. Although the detailed molecular etiology of the hyperplastic process remains to be fully established, it has been shown to be influenced by a combination of androgens, growth factors, estrogens, and epithelial-stromal interactions.10 Contrary to historical texts, androgens do not directly cause BPH, as there is no direct relationship between the concentration of serum androgens and prostate volume in aging men. However, testicular androgens do have a role, as men castrated before puberty do not develop BPH. In the prostate, testosterone is converted by the enzyme 5α-reductase to dihydrotestosterone, the principal driver of androgen-dependent gene transcription and protein synthesis, resulting in cell proliferation. Inhibition of 5α-reductase is used clinically to induce prostatic involution to treat urinary symptoms secondary to BPH. BPH causes urethral intrusion and bladder outflow obstruction, resulting in compensatory changes in bladder function. The initial adaptive bladder changes maintain voiding function, but with further deterioration, the bladder muscle can become unstable and/or lose contractility. Men with BPH often experience a complex of symptoms secondary to prostatic obstruction and bladder dysfunction. A thorough and comprehensive clinical evaluation of men with LUTS is crucial because it helps render an accurate diagnosis, which, considering the multiple factors contributing to the development of male LUTS, can be difficult. A thorough evaluation also directs therapeutic intervention and treatment. The American Urological Association (AUA) and the European Association of Urology (EAU) have produced evidence-based recommendations to guide and direct clinicians managing men with LUTS.11,12 These guidelines include recommended tests that should be performed on all men during the initial evaluation and optional tests, usually undertaken in specialist urology clinics (Figure 83-2). If the initial evaluation indicates that a man with LUTS has prostate cancer, hematuria, recurrent urinary tract infection, a palpable bladder, urethral stricture, and/or a neurologic bladder disorder, he should be referred to a urology clinic for appropriate investigation and treatment. All patients should have a focused history taken, addressing urologic and systemic conditions that may cause LUTS. In addition, it is recommended that current medications be reviewed because many drugs commonly prescribed to older people have urinary tract side effects. As part of the history, a self-completed validated symptoms questionnaire can be used to objectively assess and stratify men with LUTS. The questionnaires routinely used in clinical practice were not designed to be used to make a differential diagnosis but were developed to assess the severity of symptoms and to objectively measure the impact of specific therapeutic interventions. The two most commonly applied questionnaires are the AUA symptom score (Table 83-2) and the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), both of which contain seven symptom questions addressing urinary frequency, nocturia, weak urinary stream, hesitancy, intermittency, incomplete bladder emptying, and urgency. Each symptom is scored on a scale of 0 (not present) to 5 (almost always present) and then summed to stratify the symptom complex as mild (total score 0 to 7), moderate (total score 8 to 19) or severe (total score 20 to 35). The IPSS has an additional disease-specific quality-of-life question: “If you were to spend the rest of your life with your urinary condition the way it is now, how would you feel about that?” A limitation of the AUA score and the IPSS is that they do not address the perception of intrusion on daily life associated with each symptom, unlike other but longer questionnaires such as the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire13 and the Danish Prostate Symptom Score.14 In patients with significant storage LUTS (i.e., frequency, urgency, and nocturia), a frequency volume chart (FVC) is often very useful. The FVC records the volume and time of each void self-recorded by the patient, from which the voiding frequency, total voided volume, and fraction of urine produced during the night can be calculated. To reduce errors, it is recommended that a FVC should be collected over at least 3 days but not too long to cause noncompliance. The FVC will identify 24-hour polyuria (>3 L/24 hr) and nocturnal polyuria (>33% of the 24-hr urine output at night), which can be managed with lifestyle advice and reduced fluid intake.15 The physical examination should always include a digital rectal examination (DRE) to assess the shape, symmetry, nodularity, and firmness of the prostate gland, which can be altered in disease states. Normally, the prostate has a consistency similar to that of the contracted thenar eminence muscle of the thumb (opposition of the thumb to the little finger). It is important to note that nodularity within the prostate gland may be secondary to benign pathology, such as BPH, rather than prostate cancer. Although prostate volume estimation is not crucial in the decision process as to whether a man needs active treatment for his LUTS/BPH, it does have an important role in selecting the most appropriate medical or surgical intervention in those who do need intervention. As assessment of prostate volume by DRE is very unreliable, and often overestimates the volume of small prostates and underestimates the volume in larger glands, prostate size is more accurately measured by ultrasound examination. Despite the lack of robust evidence, both AUA and EAU guidelines recommend obtaining urinalysis in the routine assessment of men with LUTS. The test is inexpensive and is used to screen for urinary tract infection, diabetes mellitus, and hematuria. If the latter is present, then diagnostic flexible cystoscopy and upper urologic tract imaging should be considered. The role of renal function assessment by serum creatinine or estimated glomerular filtration rate in the investigation of LUTS is controversial. The AUA doesn’t recommend obtaining these tests in routine assessment, but the EAU states that “renal function must be performed if renal impairment is suspected, based on history and clinical examination or in the presence of hydronephrosis or when considering surgical treatment for male LUTS.” Men with BPH and renal insufficiency have increased risk of postoperative complications, including an increased risk of mortality. Although there is no role for routine imaging of the upper urinary tract in men with LUTS, renal ultrasonography is useful in men who are found to have an elevated serum creatinine, hematuria, or a urinary tract infection. Localized prostate cancer commonly coexists with BPH in older men and can lead to LUTS by producing bladder outflow obstruction. Although the diagnosis of a locally advanced prostate cancer will usually influence the management of LUTS, the detection of small volume prostate cancer in an older man is unlikely to reduce his life expectancy. Therefore, prostate cancer screening by PSA measurement should be done only if a diagnosis of prostate cancer will influence the clinical management of a patient with LUTS. In specialist units, assessment of urinary flow rate with a noninvasive flow meter (uroflowmetry) is routinely part of the investigations for men with LUTS. In this test the patient voids into a device that measures the volume of urine voided over time, from which the maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax) is calculated. For the results of uroflowmetry to be valid, the patient needs to void more than 150 mL of urine. As a diagnostic test, uroflowmetry has limitations, as it assesses bladder muscle contraction as well as urine flow through the prostate and penile urethra. Therefore, a low urine flow rate may indicate detrusor impairment rather than BOO. Nevertheless, it is a useful and quick test to evaluate male patients for suspected BOO secondary to BPH. A Qmax of less than 10 mL/sec is highly suggestive of BOO, whereas very few men with Qmax greater than 15 mL/sec have obstruction. BPH can lead to incomplete bladder emptying and what is often referred to as a postvoid residual (PVR) volume of urine. This volume can be determined by in-out catheterization or, more commonly, by bladder ultrasound scan. Normally the bladder completely empties on voiding. If BOO due to BPH is clinically suspected and flow rate and PVR are equivocal, then further urodynamic assessment with pressure-flow studies can be considered. Computer pressure-flow studies measure the pressure in the bladder using an electronic transducer passed into the bladder along the urethra. The test is the most accurate method to differentiate men with a low urine flow rate caused by obstruction or impaired bladder muscle contraction. Pressure-flow studies also assess for involuntary bladder muscle contractions (detrusor overactivity) during the bladder-filling phase before voiding. A study of 1271 men with clinical BPH and evaluated by urodynamics found that nearly 61% had detrusor overactivity.16 Multivariate analysis showed that age and the grade of BOO were independently associated with detrusor overactivity. However, it is important to note that although BOO and detrusor overactivity often coexist and are age-related phenomena, the pathophysiologic mechanisms linking the two have not yet been established. The EAU recommends computer urodynamic investigation when considering surgery in men older than 80 years of age with bothersome, predominantly voiding LUTS. When considering which treatment approaches to offer a patient with LUTS secondary to BPH, it is important to consider not only the findings of the clinical assessment but also the clinical efficacy, side effects, duration of treatment response, and effect on disease progression of the various therapeutic options. Also, many men have significant comorbidity and/or frailty, which will need to be incorporated into the treatment discussion process. Many men who have symptomatic BPH opt to avoid or at least defer medical intervention, especially if they perceive that their symptoms are not too bothersome, or they are concerned about the potential side effects of medical or surgical intervention, or if significant comorbidity/frailty is present. Once reassured that their symptoms are not secondary to cancer or other serious pathology and that delaying active treatment will not have irreversible consequences, they can be managed with a conservative approach, often referred to as “watchful waiting.” Self-management (e.g., fluid restriction, especially in the evening) plays an important role in the conservative management of LUTS/BPH and can reduce both symptoms and progression. Men with LUTS/BPH and their caring clinicians are often concerned about the potential risks of observation with no active treatment. It is important to emphasize and reassure these men that complications of progressive BPH are rare. Although BOO is associated with increased volumes of residual urine, there is no clear evidence that this predisposes to a significantly increased risk of urinary tract infection. Also, bladder stones due to BOO are rare and there is no indication to screen for their presence, unless clinical symptoms suggest otherwise (e.g., hematuria or urinary tract infection). The development of renal impairment caused by BPH is very uncommon, especially in people with normal renal function at baseline. In the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS) study, there were no cases of renal insufficiency among more than 3000 men observed for more than 4 years.17 The most patient-feared risk involved in watchful waiting for BPH is the development of acute urinary retention. In the past, acute urinary retention was an indication for surgical intervention (e.g., transurethral resection of the prostate [TURP]), and today many men go straight to TURP or have surgery if a trial without catheter is unsuccessful. From a patient’s perspective, acute urinary retention is often painful and a time-consuming process, necessitating a hospital visit and treatment that, from the health care provider perspective, is costly. A meta-analysis of the placebo arms from three medical therapy trials for BPH reported that the incidence rate of acute urinary retention was 14/1000 patient-years.18 The risk factors for acute urinary retention include advanced age, symptom severity, increased PSA value, and prostate volume. The outcomes of watchful waiting in men with LUTS and BPH have been evaluated in a large study comparing conservative therapy and TURP. At 5 years, 36% of men crossed over to surgery, leaving the majority on conservative follow-up.19 As mentioned, a key component of watchful waiting is patient reassurance and education, which includes the provision of lifestyle advice. Reduction of fluid intake in the evening can reduce nocturia and avoiding or reducing alcohol and/or caffeine consumption can have a positive effect on urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia. Postmicturition dribbling can be improved with the simple technique of urethral milking. Since the 1980s, there has been a shift in the treatment of LUTS secondary to BPH from surgical intervention to medical therapy. Unless there is an absolute indication for surgery, patients more commonly opt for drug treatment on the basis of efficacy and fewer and less severe side effects. Medical therapies for LUTS/BPH include α-adrenergic blockers, 5α-reductase inhibitors, antimuscarinic drugs, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, and combinations of these drugs. Despite the absence of clinical trial evidence, many patients also self-medicate with a wide variety of plant extracts that are marketed to have a beneficial effect on LUTS. It is commonly believed that α1-blockers mediate their clinical effect by improving bladder outlet obstruction through the reduction of smooth muscle tone in the bladder neck and prostate. However, α1-blockers have been shown to have very little effect on urodynamically proven BOO, and the mechanisms of action are probably mediated through the bladder and central nervous system as well as in the prostate. α1-Blockers are considered the first-line drug therapy for BPH-related symptoms because of their rapid onset of action, good efficacy, and low rates of significant side effects. Five α1-blockers (alfuzosin, doxazosin, tamsulosin, terazosin, and silodosin) have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States for the treatment of symptoms related to BPH. Despite the different pharmacokinetic properties of these α1-blockers, they have similar clinical efficacy in appropriate doses.20 Symptom improvement may take a few weeks, but most patients notice a benefit in a matter of days. Long-term studies have reported that α1-blockers appear to have more efficacy in men with smaller prostates (<40 mL) than those with larger glands.21 Also, α1-blockers do not prevent BPH progression with the associated risk of acute urinary retention and the need for surgical intervention.17,21 The most common side effects of α1-blockers are dizziness and orthostatic hypotension, with the latter being more common with terazosin and doxazosin than with alfuzosin and tamsulosin. With advancing age, orthostatic hypotension increases in frequency, even in otherwise healthy and unmedicated men. Therefore, care must be taken when prescribing α1-blockers to older people.22 Tamsulosin causes ejaculatory dysfunction in up to 10% of men. This side effect is often referred to as retrograde ejaculation, secondary to the passage of seminal fluid through an α1-blocker–induced open bladder neck. Ejaculatory dysfunction is also possibly related to a decrease in seminal fluid production. α1-Blockers, particularly tamsulosin, have been shown to increase the risk of intraoperative floppy iris syndrome in cataract surgery.23 This syndrome is characterized by a flaccid iris that prolapses toward the incision site and progressive intraoperative miosis. The reported risk of intraoperative floppy iris syndrome among men taking tamsulosin ranges widely (from 43% to 90%), and it remains to be established whether stopping α1-blocker treatment before surgery reduces the risk of this complication.11 It is good practice to ask about any planned cataract surgery before prescribing an α1-blocker and to defer the drug if necessary. 5α-Reductase inhibitors act on the prostate by inhibiting the enzyme (5α-reductase) that converts testosterone to the more potent androgen, dihydrotestosterone. 5α-Reductase exists in two isoforms, 5α-reductase type 1 and 5α-reductase type 2, which is predominantly expressed in the prostate. The FDA has approved two 5α-reductase inhibitors (finasteride and dutasteride) for the treatment of BPH-related LUTS. These agents differ in that finasteride inhibits only 5α-reductase type 1, whereas dutasteride inhibits 5α-reductase types 1 and 2. Whether this difference is clinically relevant is unclear as there are no data from direct comparator trials. 5α-Reductase inhibitors work by causing apoptosis of prostatic epithelial cells, leading to a reduction in prostate volume by 18% to 28% and serum PSA level by 50% after 6 to 12 months. Because of their mechanism of action, 5α-reductase inhibitors are not recommended for the treatment of LUTS in the absence of prostatic enlargement. Although 5α-reductase inhibitors are less effective than α1-blockers at relieving LUTS in the short term, they significantly reduce the progression of LUTS secondary to BPH, the related risk of acute urinary retention, and the need for surgery.17,24 The most commonly experienced side effect of 5α-reductase inhibitors is sexual dysfunction, including reduced libido, ejaculatory dysfunction, and erectile dysfunction. These side effects are reversible. 5α-Reductase inhibitors have been used in two large prostate cancer chemoprevention trials. Both of these studies reported that, in the 5α-reductase inhibitor treatment arm, the incidence of prostate cancer was significantly lower,25,26 but 5α-reductase inhibitors are not yet FDA approved for prostate cancer prevention. 5α-Reductase inhibitors also have application in the management of refractory hematuria secondary to benign prostatic bleeding. It is important to note that other causes of hematuria (e.g., bladder and renal cancer) need to excluded before a diagnosis of benign prostatic bleeding is made in an older male. Many men with voiding LUTS secondary to BPH also experience storage symptoms (e.g., urgency, frequency, and nocturia). While voiding symptoms are typically managed with an α1-blocker, a 5α-reductase inhibitor, or both, storage symptoms are often treated with antimuscarinic drugs. This class of medication reduces smooth muscle contraction in the bladder and may also have a clinical effect by modulating the bladder lining (urothelial cells) and the central nervous system. The most common reported side effects of the antimuscarinic drugs are dry mouth, constipation and voiding difficulties. It is because of the latter that the AUA recommends that before initiating antimuscarinic therapy, the baseline PVR urine should be assessed and caution should be taken in patients with a PVR volume greater than 250 to 300 mL. If prescribed, it is good practice to monitor the IPSS and PVR urine and warn patients about the risks and symptoms of urinary retention. Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors work by reducing smooth muscle contraction and tone in the bladder, prostate, and penile tissues. Three oral PDE5 inhibitors have been licensed for the treatment of erectile dysfunction, but only one (tadalafil 5 mg once daily) is approved by the FDA for the treatment of male LUTS. A meta-analysis of PDE5 inhibitor monotherapy reported a significant improvement in erectile function (assessed by the International Index of Erectile Function and the IPSS) but no improvement in the maximum urine flow rate compared with placebo.27 PDE5 inhibitors are contraindicated in patients using nitrates because of the risk of hypotension, myocardial infarction, and stroke. Side effects of PDE5 inhibitors include headache, flushing, dyspepsia, nasal congestion, and myalgia. A wide variety of products containing plant extracts are marketed to relieve male LUTS. The most commonly used plants include saw palmetto, stinging nettle, South African star grass, pumpkin seeds, and bark of the African plum tree. Because of brand and batch variability, interpretation of the clinical efficacy of these agents in published clinical trials and meta-analyses is extremely difficult. Therefore, the AUA does not recommend any dietary supplement or other nonconventional therapy for the management of LUTS secondary to BPH.

The Prostate

Introduction

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

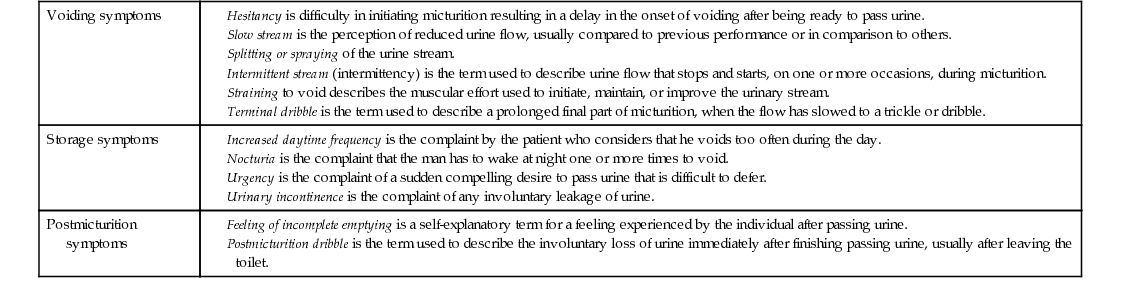

Voiding symptoms

Storage symptoms

Postmicturition symptoms

Prevalence of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Benign Prostate Hyperplasia in Men

Pathogenesis of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Clinical Assessment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

Optional Test Performed in Specialist Units

Treatment Options for BPH

Conservative Therapy (“Watchful Waiting”)

Drug Therapy

α1-Adrenoceptor Antagonists (α1-Blockers).

5α-Reductase Inhibitors.

Antimuscarinic Medications.

Phosphodiesterase 5 Inhibitors.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Prostate

83