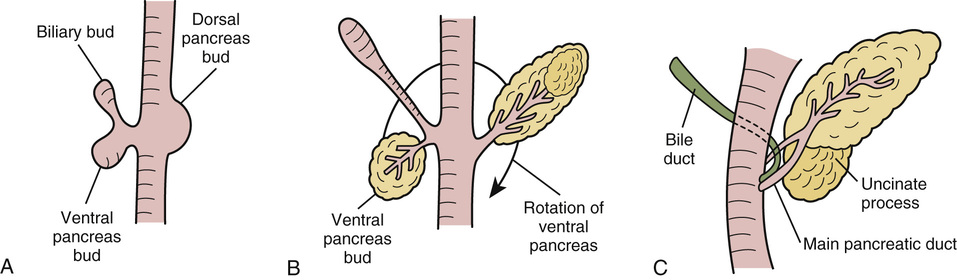

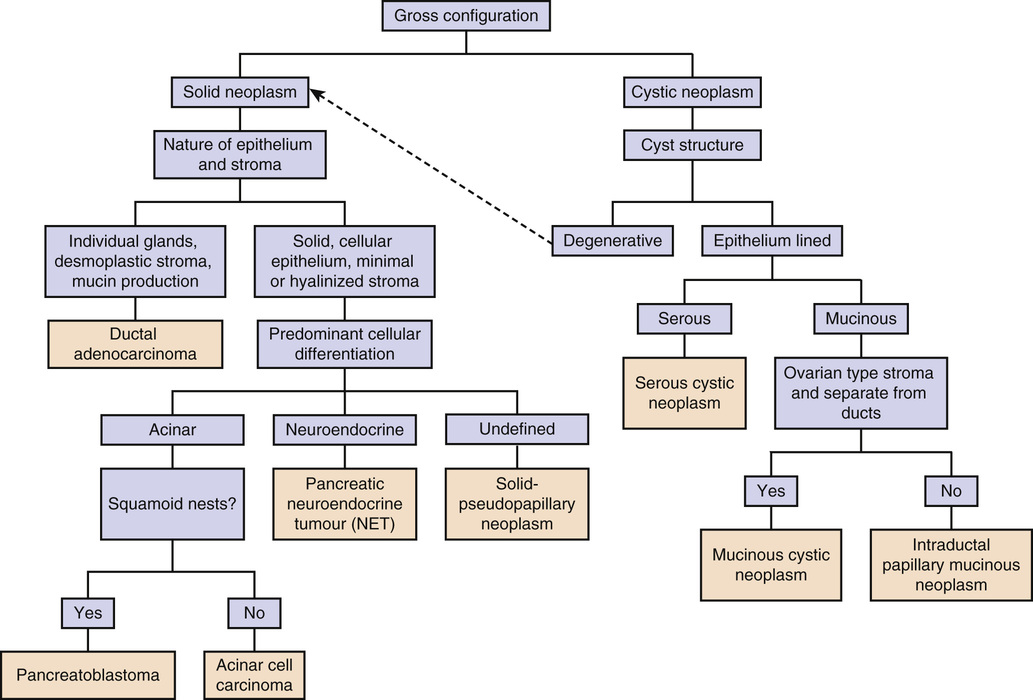

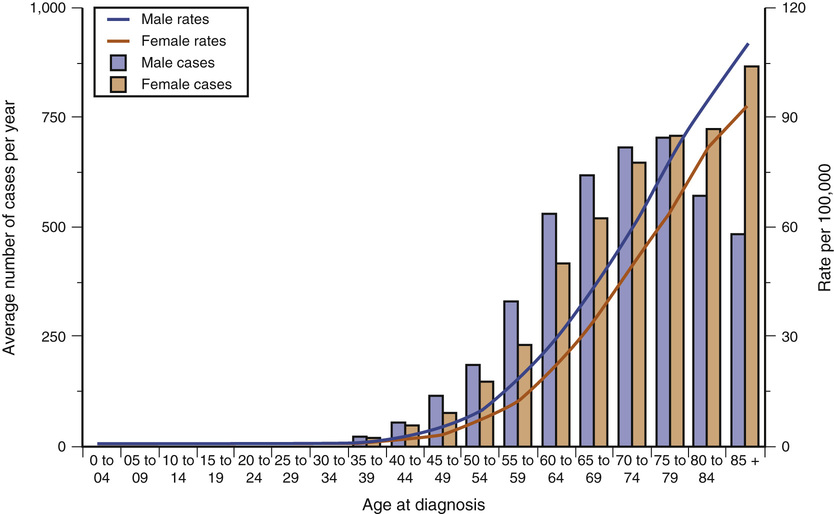

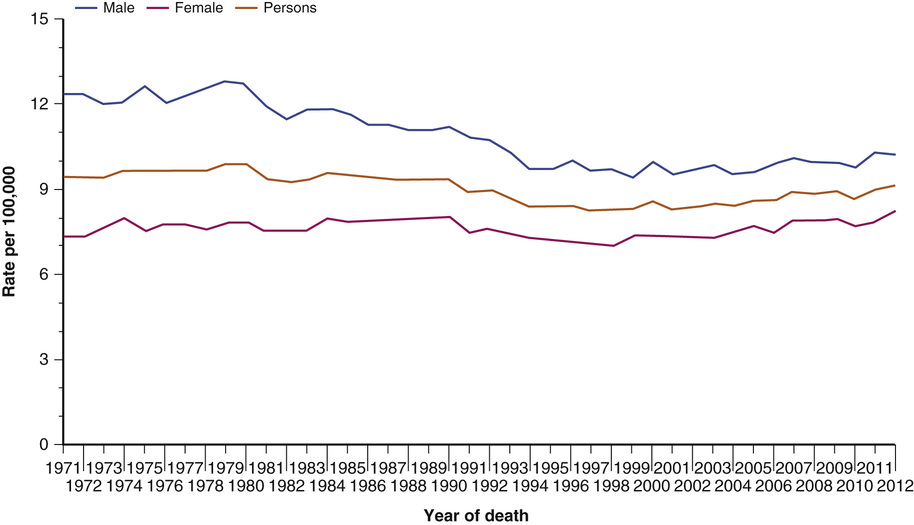

J.C. Tham, Ceri Beaton, Malcolm C.A. Puntis The pancreas is a retroperitoneal organ located deep to the stomach; it has endocrine and exocrine functions. Some knowledge of its development and structure is necessary as a foundation on which to base an understanding of the diseases that affect it and its changes with age. The pancreas begins to develop at day 26 as dorsal and ventral endodermal buds arising from their respective aspects of the primitive tubular foregut. The ventral bud arises together with the embryonic bile duct, and it then migrates posteriorly around the duodenum. Late in the sixth week, the two pancreatic buds fuse to form the definitive pancreas (Figure 73-1).The dorsal pancreatic bud gives rise to part of the head, body, and tail of the pancreas, whereas the ventral pancreatic bud gives rise to the uncinate process and remainder of the head. The two ductal systems fuse, and the proximal end of the dorsal bud duct usually degenerates, leaving the ventral pancreatic duct as the main duct opening at the ampulla. The opening of the dorsal duct, if it persists, forms the accessory duct. The pancreatic endoderm of each bud develops into an epithelial tree that will form the duct system, which drains the exocrine products manufactured in the acini. Endocrine cells arises separately from the ducts and aggregate into the islets.1 A failure of migration or fusion of the early pancreatic buds can result in pancreas divisum, which occurs in about 7% of the population. Alternatively, the pancreas can surround the duodenum, resulting in an annular pancreas. Abnormal development of the ventral duct can result in a common channel whereby the junction of the biliary and pancreatic ducts is outside the wall of the duodenum, allowing reflux and mixing of bile and pancreatic juices, which can result in damage to the bile duct in the fetus and a choledochal cyst or damage to the pancreas, causing acute pancreatitis. The adult pancreas is a retroperitoneal structure 12 to 15 cm long, extending from the duodenum to the hilum of the spleen. The neck of the pancreas lies anterior to the superior mesenteric vein, and the uncinate process curls around the vein to lie on its right, on the posterior border. Posterior to the head and uncinate process is the inferior vena cava. The splenic artery and vein pass deep to the upper border of the pancreas and provide much of its vascular supply. The right-hand border of the head is closely applied to the concavity of the duodenum, and its superior part is related to the portal vein. The pancreas has a lobulated structure, and there are intralobular ducts penetrating the secretory acini, which are flask-shaped structures consisting of typical zymogenic cells. The larger interlobular ducts contain some nonstriated smooth muscle. The million or so islets of Langerhans are distributed throughout the adult pancreas and consist of endocrine cells. The alpha cells constitute 15% to 20% of the islet cells and produce glucagon. The insulin-secreting beta cells comprise about 65% to 80% of the islet cells, and the delta cells comprise about 3% to 10% of the islet cells and produce somatostatin. The PP (gamma) cells (3% to 5%) produce pancreatic polypeptide, and the epsilon cells (<1%) produce ghrelin. The pancreas secretes 1400 mL/ day of an alkaline, bicarbonate-rich solution containing proenzymes that are converted into active enzymes—proteases, lipases, and glycosidases, such as amylase. In the gut, a proenzyme-like trypsinogen is converted into trypsin by enterokinases; trypsin then in turn releases more trypsin from trypsinogen. Enzyme secretion is stimulated by cholecystokinin, which is released by the duodenum in response to the presence of food. Secretin, also released from the gut wall, controls the secretion of water and electrolytes, most of which are secreted from the ducts of the pancreas.2 Pancreatic exocrine function deteriorates with age; the secretion of bicarbonate and enzymes have been found to be reduced in a group of subjects, average age 72 years, compared with a group whose average age is 36 years.3 However, 80% to 90% of pancreatic function must be lost before malabsorption becomes apparent; this happens only occasionally in the older patient, in whom other causes of malabsorption are more common.4 Synthesis and release of insulin from the beta cells of the pancreas is controlled by the level of glucose in the beta cells, which reflects the plasma level. However, overall control of pancreatic function is the result of many complex and interrelated feedback loops. Somatostatin, for example, secreted from the delta cells in response to an increasing blood sugar level, inhibits enzyme release and decreases gut motility. The full complexity of the hormonal control of glucose in the body is as yet not fully elucidated; however, it is clear that there are some functional changes with age.5 As well as age-related changes in pancreatic function after the age of 60 years, there are morphologic changes in that the pancreas shrinks and can become more fatty.6 Patchy fibrosis can also occur in the pancreas from the seventh decade onward, but without the other changes of chronic pancreatitis this age-related focal lobular fibrosis is associated with ductal papillary hyperplasia, which can be premalignant.7 The classification of pancreatic neoplasia can be grouped into two main groups—cystic and solid neoplasia—as shown in the algorithm in Figure 73-2. Ductal adenocarcinoma is the most common pancreatic tumor, accounting for 85% of all tumors in the pancreas; it is a malignant tumor with a very poor prognosis.8 Truly benign tumors such as fibromas, lipomas, and hemangiomas do occur but are exceedingly rare. This chapter will discuss the more common pancreatic neoplasms. The exact nature of a cystic lesion in the pancreas is still difficult to identify in spite of the use of computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound (US) by transcutaneous and endoscopic techniques. It is often difficult to distinguish an inflammatory lesion from a neoplasm.9,10 Biopsy is often difficult or inconclusive, and the general advice is to err on the side of resection.11 During pathologic classification of the tumor, it is important to be sure that the cyst is not a degenerative cyst because this signifies that the underlying tumor is more likely to be a solid tumor, and this will affect management. Immunohistochemistry is useful in differentiating the tumor types. Although these tumors tend to occur more commonly in younger or middle-aged individuals, they also occur up to the seventh and eighth decades and are more likely to be malignant in patients older than 70 years, when resection should be considered.12 A serous cystadenoma is sometimes known as a serous microcystic tumor. The mean age of presentation is in the sixth decade, and 70% occur in women. The vast majority are benign, and only a handful of cases of malignant serous cystic tumor of the pancreas have been reported.13 This neoplasm accounts for 50% of cystic tumors and is malignant or potentially malignant. It is most common in middle-aged women and should be treated by resection of the affected part of the pancreas.14 An intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) is a tumor that is twice as common in men as in women and has a mean age at presentation in the seventh decade. It is characterized by copious mucous draining at a patulous ampulla from a dilated duct. It has a favorable prognosis following appropriate resection.15,16 This is a rare epithelium-lined cystic lesion, histologically similar to a branchial cyst.17 This tumor results from cystic degeneration of a solid endocrine tumor. Although it is rare, it is important to consider this diagnosis when evaluating a cystic lesion in the pancreas and test for endocrine activity to exclude a functioning tumor, although most of these tumors are nonfunctioning. This is a rare genetic condition with autosomal dominant inheritance. Several types of pancreatic tumors can occur in this condition, including serous cystadenoma, multiple cysts, and endocrine tumors.18 Pancreatic cancer is the fifth most common cause of cancer death in the United Kingdom and the seventh most common worldwide.19 Patients with pancreatic cancer should undergo definitive surgery within days of diagnosis if there is an advanced health care system. However, there is usually a delay of a few weeks prior to surgical treatment. In 2011, the number of deaths from pancreatic cancer in the United Kingdom was 8320, with a rate of 13.2/100,000 population.19 The incidence of pancreatic cancer in the United Kingdom increases sharply with age, and 96% of patients with pancreatic cancer are 50 years of age or older20,21 (Figure 73-3). Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma has the lowest 5-year survival rate for all cancers, 3.6% for men and 3.8% for women in the United Kingdom, with a 2% to 9% 5-year survival rate in Europe.22 The mortality rate is similar to its incidence, reflecting low survival.19 Fortunately, the mortality rate for pancreatic cancer has decreased in the United Kingdom since the 1970s19 (Figure 73-4). Some risk factors that have been reported for pancreatic adenocarcinoma include age, alcohol, blood group A, chronic pancreatitis, diabetes mellitus, exposure to acrylamide, ionizing radiation, obesity, red meat, smoking, possible relationship to increased body mass index (BMI), and genetic factors (e.g., aerodigestive and reproductive cancers, presence of the BRCA2 gene, familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, von Hippel–Lindau syndrome, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer),23,24 Also, certain infections may result in an increased risk, such as hepatitis, Helicobacter pylori, and periodontal disease.25 However, at present, no definitive causative agents have been discovered as a clear cause of pancreatic cancer. Approximately 85% of patients present with disseminated or locally advanced disease. Symptoms frequently include epigastric or back pain, anorexia, weight loss, and obstructive jaundice.26 Pain can be caused by tumor compression of surrounding structures, tumor size, invasion of pancreatic nerves, and invasion of the anterior pancreatic capsule. Pain intensity at presentation has been found to correlate with survival (29 months for patients without pain, 9 months for those with severe pain).27 Back pain may predict unresectability and shortened survival after resection.28 Weight loss is a common presenting symptom and can be due to anorexia, catabolic metabolism, or malabsorption; however, weight loss is also a common and nonspecific symptom, especially in older patients. Sixty percent to 70% of pancreatic adenocarcinomas affect the head of the pancreas. These patients often present with obstructive jaundice due to compression of the biliary tract.21 Tumors of the body and tail of the pancreas are frequently associated with late presentation and inoperability. When an older patient presents with a new diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, the presence of an underlying pancreatic cancer should be considered, especially if the patient has other suggestive symptoms. A tumor has been found to be the underlying cause in 1% of patients older than 50 years who have been diagnosed with diabetes.29 Other presentations may include acute pancreatitis and acute upper gastrointestinal or retroperitoneal hemorrhage.21 The investigations performed in suspected pancreatic cancer are undertaken with the following aims: Cancer antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) is a glycoprotein synthesized by pancreatic cancer cells that is also produced by normal epithelial cells of the pancreas, bile ducts, stomach, and colon.30 It has been found to have a sensitivity of 70% to 90% and specificity of 75% to 90% for pancreatic cancer, but its level is also elevated in obstructive jaundice, chronic pancreatitis, and biliary and gastrointestinal cancers.30,31 Although tumor markers cannot actually confirm a diagnosis, they are particularly useful later in the patient’s management when a rise in the CA19-9 level, especially if it originally decreased after treatment, may indicate a recurrence. It is not useful as a screening test.32 Other tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) have limited use due to lower sensitivity and specificity.31 However, newer, more sensitive biomarkers are being developed. Serum, bile, salivary, and stool biomarkers based on RNA and new proteins based on proteomic studies, along with those developed as a result of genomic and epigenetic studies, have been shown to be a promising avenue but still require large studies to validate their results.33 Transabdominal US is frequently the first-line imaging investigation performed in the older patient presenting with upper abdominal symptoms. The results are variable and are dependent on the operator, patient’s body habitus, and presence of overlying gas-filled bowel loops. The sensitivity of diagnosing pancreatic cancer with US ranges from 44% to 95%.30,34,35 The highest sensitivities have been found in groups in which patients were not scanned on an intention to treat basis, and difficult scans were excluded from the analysis. CT is considered the imaging modality of choice in pancreatic cancer because it can give additional staging information by imaging the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and can provide more detailed information regarding the resectability of pancreatic tumors. Helical CT has been found to be very effective in detecting and staging adenocarcinoma, with a sensitivity of up to 97% for detection and up to 100% accuracy in predicting unresectability, although it is not as good at predicting resectability.36 When directly compared with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and MRI in a cohort of patients deemed fit for surgery, CT had the highest accuracy in assessing the extent of the primary tumor (73%), locoregional extension (74%), vascular invasion (83%), and tumor resectability (83%).37 Pancreatic CT should be conducted using a pancreatic protocol modality, which is a multiphase imaging technique that captures images during the noncontrast phase, arterial phase, late arterial phase, and portal venous phase within thin tomograms (3 mm) for precise delineation of any pancreatic lesion and assessment of vascular involvement.38 The value of CT in predicting resectability, however, can be as low as 38%, with patients predicted to have resectable disease on CT found to be unresectable at laparotomy; the most common causes of unresectability include liver metastases and vascular involvement of the tumor.36 The contrast medium used for CT is potentially nephrotoxic, patients must be well hydrated, and the serum creatinine level checked because this may be a problem, especially in older patients in whom renal impairment is more common. MRI is comparable to CT in assessing the extent of vascular and lymphatic involvement but may be more sensitive in detecting hepatic and peritoneal disease.38 Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) has been shown to be as diagnostically effective as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in patients with symptoms suggestive of pancreatic cancer (84% sensitivity, 97% specificity).39 MRCP has the added advantage of fewer complications, compared with ERCP, although a number of older patients are unable to tolerate the confined space in an MRI scanner. In the diagnosis of cancer of the pancreas, ERCP has a sensitivity and specificity of 70% and 94%39 and offers the opportunity to obtain a cytologic diagnosis by sampling bile or taking brushings. The value of such sampling can be questionable, however, because a sensitivity of only 60% has been reported, with a specificity of 98%.40 ERCP can have serious complications, such as pancreatitis, cholangitis, hemorrhage, and death. In addition to being an investigative tool, especially in older patients, ERCP can be used for treatment, such as stent placement, and may be the treatment of choice, rather than resection. EUS has been rapidly growing in importance. The high-frequency ultrasound probe positioned in the stomach and duodenum allows high-resolution imaging of the pancreas and surrounding tissue. The accuracy of EUS in evaluating tumor and nodal status has been found to be 69% and 54%, respectively,41 and EUS has been found to be at least as valuable as CT42 and equal if not superior to CT for evaluating vascular invasion.43 EUS also offers the opportunity of performing fine needle aspiration of the tumor to aid diagnosis. However, in potentially resectable patients, this should generally only be performed via the duodenum rather than the stomach because the duodenum will be removed during resection, and there have been concerns regarding seeding malignant cells in the needle track. Positron emission tomography (PET) exploits the increased glucose metabolism observed in malignant tumors, which has been found by administering a radioactive glucose analogue and then scanning for increased uptake by tumor cells. PET images may be captured concurrently with CT images to aid in localizing any accumulation of tracer. PET is useful in diagnosing small (<2 cm) tumors and has sensitivity and specificity as good as that of EUS, ERCP, and US. It is particularly useful in detecting distant metastasis—for example, cervical nodes.44 Currently, PET with or without CT is not superior over MRI or CT alone in diagnosing pancreatic cancer but is useful in staging and predicting survival.45 The only curative treatment for pancreatic cancer is surgical resection, and the proportion of patients considered to be resectable has increased26 due to the development of new techniques and oncologic management.46–49 Preoperative imaging is useful for determining clearly inoperable tumors but, at operation, more will be found to be inoperable because of local or distant involvement of other tissue. For consideration as being resectable on imaging, there should be no involvement of the superior mesenteric artery or celiac axis and no evidence of distant metastasis. Recent consensus has suggested that resection is possible in selected patients with short segment venous occlusion in the superior mesenteric vein or portal venous axis, and possibly even arterial involvement. Such radical surgery does not appear to result in a significant increase in morbidity nor, however, an increase in survival.49 The absence of improvement in survival rate may be related to undetectable distant metastasis and local spread.50 In the jaundiced patient, ERCP for stenting prior to surgery had no benefit on morbidity and mortality compared to the nonintervention group.51 However, when morbidity is scrutinized, it was noted that in the stent group, the postoperative complications were lower but there was a higher preoperative complication rate; patients had an increased risk of cholangitis.51 Surgical options for resecting cancer of the head of the pancreas include distal pancreatectomy, the traditional Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy, or a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD). PPPD involves dividing the bile duct close to the liver hilum, dividing the duodenum 2 cm beyond the pylorus, dissecting the pancreas off the superior mesenteric vein, and dividing the pancreas between the head and neck, with division of the small bowel at the duodenal-jejunal flexure. The reconstruction then involves three anastomoses—restoring gut continuity by a pylorus-jejunal anastomosis, connecting the stump of the bile duct to the jejunum just distal to the pylorus-jejunal anastomosis, and a pancreatic anastomosis. We prefer a pancreaticogastric anastomosis rather than the alternative pancreaticojejunal anastomosis, but the published leakage rate of this technique is up to 10% in some series.52 Currently, most surgeons use the technique that gives them good results in their hands. The Whipple procedure differs in that a distal gastrectomy is also performed. It would be expected to cause possible long-term morbidity due to gastric dumping, marginal ulceration, and bile reflux gastritis when compared to the PPPD. There have been questions regarding the adequacy of resection in a PPPD, but a Cochrane review in 2011 demonstrated no significant difference between a Whipple procedure and PPPD in terms of in-hospital mortality, overall survival, and morbidity, apart from shorter operative time in the PPPD.48 The overall complication rate for PPPD is around 39%, with mortality ranging from 0% to 7%.48,53,54 Early complications, including postoperative bleeding and bile leak, have been quoted at rates of 4.8% and 1.2%, respectively, in a meta-analysis.48 Other significant early complications of particular importance in older adults due to preexisting comorbidities include cardiac and respiratory complications; older patients have been shown to be treated for significantly more cardiac events following PPPD (13% vs. 0.5%).55 Late complications related to the nature of the operation include delayed gastric emptying, which occurs in 29% of PPPD patients, and pancreatic fistula in 7.2%.48 A surrogate marker for significant complications is the necessity for reoperation, which is required in 9.9% of patients.48 Pancreatic endocrine function is generally maintained,56 and pancreatic exocrine function should be assessed by measuring fecal elastase levels, because malabsorption will result in malnutrition postoperatively.57 Surgery for cancer of the body and tail of the pancreas is less frequently performed because patients usually have only nonspecific symptoms, and a diagnosis is often only made when the tumor is inoperable. When a distal pancreatectomy is possible, it involves dissecting the pancreas off the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), dividing the pancreas, and oversewing the cut end. A splenectomy is also performed in cancer operations to ensure as much oncologic clearance as possible. With the development of more advanced surgical techniques, laparoscopic surgery can now be performed in more complex cases. Compared to open distal pancreatectomy, the laparoscopic procedure is associated with less blood loss and therefore a lower transfusion rate, fewer wound infections, lower morbidity, and shorter hospital length of stay, without any compromise in oncologic outcome.47 With advancing technology, robotic surgery has now been tested in pancreatectomy. A recent systematic review on robotic pancreatectomy has suggested that it is comparable to open pancreatectomy and laparoscopic pancreatectomy, with a conversion rate of 14%, mortality rate of 2%, morbidity rate of 58%, and only a 7.3% reoperation rate.58 The question of the appropriateness of performing surgery of such magnitude in an older patient is an important one. The patient should be evaluated on an individual basis with regard to comorbidities and fitness for an anesthetic, possibly using assessments such as POSSUM (a multifactorial scoring system)59 and cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPEX), which defines the physiologic stress level at which the patient becomes anaerobic.60 Patients must be made fully aware that their short-term function and nutritional condition may be compromised after a major pancreatic resection.55 It has been demonstrated that patients older than 75 years undergoing pancreatic surgery for cancer, when compared with patients younger than 75 years, have an increased mortality rate (10% compared with 7%), are more frequently admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) unplanned (47% compared with 20%), are treated for more cardiac events (13% vs. 0.5%), are more likely to have a compromised nutritional and feeding status, and are more likely to be transferred for further nursing care prior to discharge home.55 In older patients, it is particularly important to consider the potential impact of surgery on the quality of life and the need for prolonged rehabilitation. The operative mortality for pancreatic cancer surgery has been shown to increase with advancing age—7% at 65 to 69 years, 9% at 70 to 79 years, and 16% at 80+ years.61 Some studies, however, when looking at significant predictors of survival, have not found age to be an independent variable.62,63 For patients with unresectable disease, the three most important symptoms for palliation are pain, jaundice, and gastric outlet obstruction (GOO). A multidisciplinary team consisting of representatives from surgery, medical oncology, gastroenterology, radiology, and palliative care medicine is essential for the optimal palliation of symptoms.64 The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to pain management in patients with advanced cancer is still recommended,65 and analgesics should be titrated according to the three-step analgesic ladder: (1) nonopioids, including nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); (2) weak opioids; and (3) strong opioids. Attention should be paid to the route of administration in pancreatic cancer patients because GOO may be present and the absorption of oral analgesics may be unpredictable. In patients with severe pain, a celiac plexus block (CPB) with neurolytic solutions may provide analgesia by interrupting visceral afferent pain transmission from the upper abdomen. This can be performed percutaneously, surgically (at the time of laparotomy or bypass), or under EUS guidance. In a prospective, randomized, double-blinded placebo-controlled trial, percutaneous CPB with absolute alcohol has been shown to improve pain relief significantly in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer compared with opioids, although CPB did not affect quality of life or survival.66 The major complications from percutaneous CPB include lower extremity weakness, paresthesias, lumbar puncture, and pneumothorax at a rate of 1%. The technique of EUS-guided CPB has become more popular and has been found to be safe and effective in pancreatic cancer.67,68

The Pancreas

Background

Development of the Pancreas

Anatomic Relationships

Histology

Exocrine Function

Endocrine Function

Age Changes

Tumors of the Pancreas

Cystic Tumors

Serous Cystadenoma

Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm

Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm

Lymphoepithelial Cyst

Cystic Islet Cell Tumors

Von Hippel–Lindau Syndrome

Solid Tumors

Ductal Adenocarcinoma

Epidemiology and Age Incidence.

Presentation.

Pain.

Weight Loss.

Jaundice.

Other.

Diagnosis

Blood Tests

Serum Antigens.

Imaging

Transabdominal Ultrasound.

Computed Tomography.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography.

Endoscopic Ultrasound.

Positron Emission Tomography.

Management

Resectable Disease

Unresectable Disease

Pain.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Pancreas

73

Figure 73-3 Incidence rate of pancreatic cancer in the United Kingdom, 2009-2011. (From Cancer Research UK: Pancreatic cancer incidence statistics. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/pancreatic-cancer/incidence. Accessed December 3, 2015.)

Figure 73-4 European age-standardized mortality rates from pancreatic cancer in the United Kingdom, 1971-2012. (From Cancer Research UK: Pancreatic cancer mortality statistics. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/pancreas/mortality/uk-pancreatic-cancer-mortality-statistics. Accessed December 3, 2015.)