Chapter 21 THE OLDER PERSON WITH SUICIDAL THOUGHTS

INTRODUCTION

Some of the highest rates for suicide are found among older people, particularly men. Yet despite this fact, older people are often left out of discussions on suicide for a number of reasons (Mitty & Flores 2008). These include more emphasis given to youth suicide because the young carry a higher economic burden and, where ageist attitudes prevail, feelings of wanting to die and hopelessness are sometimes considered normal for older people. Unfortunately, these attitudes also manifest in clinical practice where it may not be considered important to ask an older person about suicidal feelings and, consequently, they are less likely to be offered assertive treatment (O’Connell 2005).

There has been a significant decline in late-life suicides over the last decade or so (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2007). However, the increased prevalence of depression and suicide attempts among middle-aged people, particularly the large number of baby boomers who are now beginning to reach the status of being older people, may be suggestive of a generational effect that will carry over into the coming decades, boding late-life suicide as a looming major public health concern. Suicide is a tragic event for all the people involved, including mental health workers. The purpose of this chapter is to highlight the trends and themes concerning suicide and older people, and create an awareness of risk factors and the role they have in the prevention of suicide. Effective interventions are also detailed to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with suicide in older people.

CASE VIGNETTE

Tom is a 67-year-old, unmarried, retired farmer. He had been discovered by his neighbour early one morning preparing to hang himself from a tree in the backyard. The neighbour had rung the police who took Tom to the local hospital’s emergency department. Tom was admitted voluntarily to the psychiatric unit. He had been there for a week and was being discharged home. He had been referred to the older persons’ mental health service (OPMHS) on admission for intensive follow-up on discharge. Staff of the OPMHS had been involved in the treatment decisions. Tom was not cognitively impaired, he was diagnosed with a mild depression and had been prescribed an antidepressant medication.

During his admission, the following personal problems had been identified:

EPIDEMIOLOGY

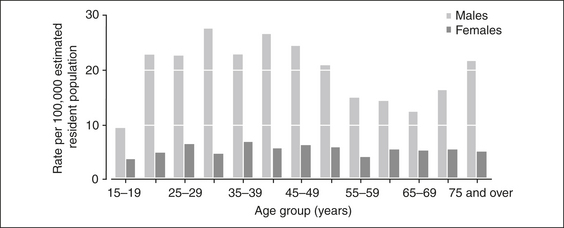

The pattern of age-specific rates in 2005 for suicide in men and women is shown in Figure 21.1.

The following are some interesting facts and figures about suicide in older people in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2007, Caldwell et al 2004, Cantor et al 1999, de Leo et al 1999, 2001, Fairweather et al 2007, Goldney & Harrison 1998):

TYPES OF SUICIDAL BEHAVIOURS

Suicidal behaviour in older people has been categorised as thoughts of hopelessness or suicidal ideation, indirect self-destructive behaviour, deliberate self-harm and completed suicide (Harwood 2002). Some very old or terminally ill people may have thoughts of hopelessness or suicidal ideation and may express statements such as ‘I wish I was dead’, but if questioned will vehemently deny any thought of self-harm. More serious suicidal thoughts are usually found when a person is single, has depression, physical disability, pain, sensory impairments or is institutionalised. Indirect self-destructive behaviour, sometimes known as subintentional suicide, such as failing to eat and drink or non-compliance with life-saving medication, occurs frequently in older women and in very old institutionalised people. The older person in this situation will deny that it is an act of suicide, but the likelihood of dying is increased. Deliberate self-harm differs from suicidal thoughts and indirect self-destructive behaviour because there is a definite, more determined and immediate response.

METHODS OF SUICIDE

In Australia (de Leo et al 2001), older men tend to use more violent and lethal means such as hanging, shooting and carbon monoxide poisoning (car exhaust fumes). This use of highly lethal means is thought to account in part for the higher rate of completed suicides in older men. Older women tend to use drug overdose, hanging and carbon monoxide poisoning. Drug overdoses are usually with commonly prescribed medications such as paracetamol, analgesics and antidepressants. Large-scale government policies, such as gun control laws, changing household gases to less toxic varieties and changing prescribing practices, have reduced the use of these popular methods for suicide; however, there have been compensatory rises in other methods, leading to the conclusion that limiting access to means of suicide to suicidal people who are ambivalent may be effective, but it does not change the behaviour of those people who are intent on committing suicide.

RISK FACTORS

Depression is the most common antecedent of suicide in older people. However, one does not have to be depressed to commit suicide, and being depressed does not necessarily make a person suicidal. Additionally, verbalising thoughts about suicide does not always indicate intent, but it does pay to investigate this further because it has been demonstrated that older people who have completed suicide are likely to have verbalised the thought to health workers, including their general medical practitioners. Personality profiles of older people who have completed suicide have described them as being hypochondriacal, not being open to novel or new experiences and neurotic (Conwell et al 2002). The box on the next page provides a comprehensive list of the demographic, social, clinical and historical risk factors that have been identified for suicidal behaviour in older people (Garand et al 2006, O’Connell 2005, Turvey et al 2002). Clearly, not all of these risk factors are causal factors and the contribution of any single causative factor remains unclear, with popular opinion relying on a complex combination of multiple factors that often overlap, creating an additive effect.