Chapter 24 THE OLDER PERSON WITH SUBSTANCE ABUSE

INTRODUCTION

Very little attention has been given to substance abuse among older people but, with the ageing population, this issue will have greater importance and prominence. Substance abuse affects a relatively small number of older people, but it has a major impact on the quality of life of the substance user and their significant others. Substance abuse exacerbates underlying illness, alters both mood and behaviour, and can result in accidents such as falls, or while doing precarious activities like driving a car (Lynskey et al 2003). With older people, it usually involves the misuse of legal (alcohol, tobacco, prescribed and over-the-counter medications), rather than illegal substances (cannabis, heroin, cocaine) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2007). Therefore, it can easily be hidden and treatment for substance abuse may be overlooked, particularly when there are other acute or chronic illnesses shadowing the true picture (Culberson 2006).

In a number of ways, the issue of substance abuse is different for older people than the younger generations. Firstly, denial is a common response when an older person is asked about substance use. This response may be given because of memory problems, shame from the stigma attached to being a substance user, a desire to continue use, or perhaps it is considered as a normal behaviour for them. Secondly, the ageing body has reduced lean body mass and total body water causing higher peak blood alcohol levels; therefore, older people react more severely to the effects of some substances due to this changed physiological makeup. Moreover, older people also take more prescription medications where there is a likelihood of adverse interactions between substances, with warfarin and digoxin being good examples (Lynskey et al 2003). In order to maintain optimal health, substance abuse should be routinely screened and assessed for and, if found to be an issue, followed up with a comprehensive treatment approach.

CASE VIGNETTE

Bill is a 79-year-old returned soldier who lives alone in a sparsely furnished, tidy, but generally neglected house. His wife had divorced him many years before, but his four adult children were on reasonably amicable terms with their father. Each of the children lived with him intermittently when they themselves were experiencing financial and social difficulties; however, this was usually the last and very short-term option. Bill admitted that the heavy use of alcohol was the main cause of the breakdown of his marriage and family dysfunction. Since retiring as a watchmaker at the age of 65 years, tight financial circumstances had resulted in him not drinking as heavily, but he now experienced frequent and severe panic attacks (up to four times per week). The panic attacks resulted in a local general practitioner (GP) making a home visit to administer intramuscular (IM) diazepam and leaving prescriptions for sedative medications. Bill’s son referred him to the older persons’ mental health service (OPMHS), as he was not satisfied with his father’s health status.

THE SPECTRUM OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Drugs of abuse (e.g. alcohol, cannabis, sedative-hypnotics and opioids) have psychoactive properties, which means that they act on the central nervous system, particularly on the mind or psyche. Drugs that have non-psychoactive properties can also be misused, and these include tobacco and over-the-counter medications (e.g. analgesics, laxatives, tonics, vitamins, and cold and flu preparations). Substance use refers to any taking of a drug, whereas abuse involves some physiological, psychological and social harm. Prolonged abuse can lead to dependency and addiction, which have certain defining criteria. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM–IV) (American Psychiatric Association 2000) provides criteria to differentiate between these terms (see Table 24.1).

Table 24.1 DSM–IV criteria for substance abuse and dependency/addiction

| Substance Abuse | Dependency/Addiction |

|---|---|

EPIDEMIOLOGY

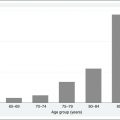

The 1997 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (Australian Bureau of Statistics 1998) established that the prevalence of substance-abuse disorders declined with age from 16.1% for 18–24-year-olds to 1.1% for those aged 65 years and older. Within that overall prevalence rate of 1.1% for older people, males recorded a rate of 2.1% compared with 0.2% for females. Older men tend to use alcohol and illegal drugs, whereas older women tend to abuse sedative-hypnotics and anxiolytics. The likelihood of using health services for a substance-abuse disorder was only 14%, whereas for affective disorders it was 56% and 28% for anxiety disorders. The decline in prevalence with increasing age is postulated as being age-related, increased mortality among those who have a lifelong history of substance abuse and less exposure and use of substances (Lynskey et al 2003).

In 2004, alcohol was the most prevalent substance used by Australians with 41% of people most likely to drink weekly and 9% consuming alcohol on a daily basis. Cannabis is the most commonly used illicit drug with 11% of people reporting to have used it in the previous 12 months; 3% of people reported the use of methamphetamines in the previous 12 months. Older people recorded the highest prevalence of daily drinking (17%), with a further 33% drinking weekly, and 25% less than weekly (12.2% stated they were ex-drinkers and 12.8% did not drink at the time of the survey) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2007). Specific data for other drugs of concern in older people, such as prescribed narcotics and sedatives and over-the-counter medications, are not available, but anecdotal accounts point to these being reasonably problematic. Also of note is that there is an expected increase in substance abuse in older people due to the ageing of the current cohort of baby boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964), who in their youth had more widespread experiences than previous generations with legal and illegal substances such as alcohol, cannabis and narcotics (Lynskey et al 2003).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The overlay of multiple medical and psychosocial issues makes the diagnosis and treatment of substance abuse in older people a complex and often frustrating experience. Substance abuse is strongly associated with a range of problems, such as self-neglect, anxiety, depression, sleep and appetite disturbances, falls, urinary and faecal incontinence, and memory problems that may be confused with the presentation of other disorders such as dementia (O’Connell et al 2003).

SCREENING TOOLS

The use of screening tools will assist in determining if a more detailed assessment of substance abuse and related issues is required. The following screening tools have been used successfully with older populations. The first two, the CAGE questionnaire and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), are primarily used for the screening of alcohol abuse (Berks & McCormick 2008), whereas the Impression of Medication, Alcohol and Drug Use in Seniors (IMADUS) has a more comprehensive approach to substance abuse and screens for alcohol, prescription drugs and over-the-counter medications (see Ch 35).

CAGE questionnaire

The CAGE questionnaire (Ewing 1984) is a 4-item, easy-to-use, reliable and valid gauge of an individual’s use of or potential abuse of alcohol and the effects it may be having on key life issues (see the box below). A ‘yes’ response to two or more of the CAGE questions is an indicator for further assessment of substance abuse, although Dekker (2002) found that a score of one or more has a sensitivity and specificity of about 80% in older people.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Saunders et al 1993) has a series of 10 questions for the identification of risky alcohol consumption. Each question receives a score from 0 to 4. A score of 8 or more is indicative of risky drinking patterns and the need for further assessment of alcohol dependence. It is short, easy to administer, and needs no formal training to administer.

Impression of Medication, Alcohol and Drug Use in Seniors (IMADUS)

The Impression of Medication, Alcohol and Drug Use in Seniors (IMADUS) (Shulman 2003) has 20 items and three or more ‘yes’ responses point to the need for a more detailed assessment. The questioning style has been designed to reduce the feelings of shame that often occur when older people are asked about substance abuse.