Chapter 22 THE OLDER PERSON WITH PSYCHOTIC SYMPTOMS

INTRODUCTION

Psychotic symptoms in older people are highly prevalent and occur in many different mental health problems, including delirium, dementia, mood disorders and psychotic disorders. Some otherwise normal older people experience hallucinations in the context of sensory impairment such as low vision or poor hearing. However, this chapter will focus on the older person with a psychotic disorder.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Psychotic symptoms occur commonly among older people. Henderson et al (1998) surveyed 935 residents of Canberra and Queanbeyan aged 70 years and over living in the community or in supported accommodation and found that 42 (4.49%) reported hallucinations and 26 (2.78%) had delusions. Overall, the estimated prevalence of at least one psychotic symptom was 5.7% for those living in the community and 7.5% for those living in supported accommodation. People with dementia or cognitive impairment were more likely to have psychotic symptoms. When these investigators resurveyed the same people 3.6 years later, there were 35 new cases of psychotic symptoms among the 581 who did not have psychotic symptoms at baseline. Thus, the incidence (new cases) of psychotic symptoms over 3.6 years was 6.0%.

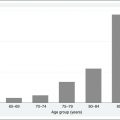

The best evidence on the prevalence of psychotic disorders in older people comes from a Finnish study (Perala et al 2007). Despite the emphasis given to young people with schizophrenia both in the mass media and within mental health services, the findings from this study indicate that psychotic disorders are actually more common in older people than in young or middle-aged people. The prevalence of non-affective psychotic disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder, and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified) in people aged 65 years and over was 2.32% (95% CI = 1.67–3.21), whereas the prevalence in people aged 30–44 years was 1.27% (95% CI = 0.89–1.82). In contrast, the prevalence of affective psychoses (bipolar I disorder and major depression with psychotic features) was very similar in middle-aged and older people: 0.57% (95% CI = 0.32–1.01) in people aged 65 years and over and 0.52% (95% CI = 0.32–0.87) in people aged 30–44 years.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Illusions and hallucinations

Hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations occur when going to sleep and waking from sleep, respectively. Similar hallucinations occur in situations of sensory deprivation, including the white noise generated by heavy rain or a bathroom shower. Strong suggestion or expectation due to mental set may also lead to simple hallucinations in normal people. Hallucinations should be distinguished from illusions, in which there is a stimulus, and from visual images, which are conscious products of the imagination.

Passivity phenomena and other psychotic symptoms

The main category of passivity phenomena is thought alienation, which includes thought insertion, thought withdrawal and thought broadcasting. In thought insertion the person experiences thoughts inserted into their mind by an outside agency, whereas in thought withdrawal thoughts are removed from their mind by an outside agency. In thought broadcasting, the person is unable to contain their thoughts within their mind and has the belief that everyone else can hear their thoughts spoken aloud. Thought withdrawal is experienced by some people as thought blocking, or the sudden cessation of a train of thought.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree