Chapter 20 THE OLDER PERSON WITH MOOD SYMPTOMS

INTRODUCTION

Depression is one of the most common mental health problems to affect older people and it usually responds well to treatment. Despite this fact, it remains underrecognised and undertreated. There appears to be a pervasive myth, at least in developed countries, that depression and old age go together because at this time of life there is a decline in physical health and older people experience significant losses, such as the loss of meaningful employment and death of a spouse. On the other hand, many older people are very satisfied with their life and look forward to what older age will bring (Nierenberg 2001). Mental health workers are in the ideal position to be aware of the key symptoms of depression, to know that older people respond to antidepressant medication and that psychological treatments may also be successful in both effecting a remission and in preventing a relapse in the longer term.

This chapter considers the prevalence of depression in older people and the clinical features of depression, and then provides a detailed outline of the clinical management of depression. Although depression is a risk factor for suicide, suicide is addressed in a separate chapter (see Ch 21), as is the closely associated topic of anxiety (see Ch 23). This chapter ends with a discussion about mania. Mania may present for the first time in an older person and it is often associated with serious comorbidity.

CASE VIGNETTE

Michael, aged 83, had been referred to the OPMHS by his general practitioner (GP) for treatment of depression. The GP had tried to treat Michael’s severe depression with a combination of antidepressant and antipsychotic medication, but Michael had experienced serious complications, including frequent falls. In the initial interview, the following history emerged. Michael had been born in Australia and was of Anglo-Saxon origin. Although retired for a considerable number of years, he had spent his working life as a motor mechanic. Nowadays, he occupied his time by meticulously maintaining his house and garden. He had been married to Doris for 55 years and they had three sons, all of whom were well established with their own families and businesses in the same town as their parents. The family relationships were assessed as being functional and close.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Depression is a global health problem and soon it will rate as the second largest cause of disease burden (World Health Organization 2001). The age-adjusted community prevalence of clinically significant depression in older Australians is 8.2% (95% CI = 7.8–8.6%), with the rate for men at 8.6% (95% CI = 7.9–9.2%) and women at 7.9% (95% CI = 7.4–8.4%). The male and female age-adjusted rate for ‘major depressive episode’ is 1.8% (95% CI = 1.6–2.0%) (Pirkis et al 2009). However, in environments where there is a concentration of older people, such as RACFs, the prevalence of depressive illness increases, with reported figures around 10% (O’Connor 2006). It is also well established that up to 30% of older people who are medical patients in general hospitals have major depression (Cole 2008). Recent spousal bereavement, functional impairment and physical illnesses, such as myocardial infarction, stroke and cancer, all increase the likelihood of an older person developing a depressive illness (Pfaff et al 2009).

Depression can present with varying severity. Criteria for major depression, dysthymia and adjustment disorders with depressed mood are outlined in The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association 2000) (see the box below). Differentiating between the different types of depression depends upon the duration and number of symptoms. Dysthymia is a chronic low-grade depression, while adjustment disorders with depressed mood are depressive reactions to adverse life events that do not meet diagnostic criteria for major depression. Major depression is the most clinically significant and will be the focus of this chapter.

RISK FACTORS

Risk factors for depression include:

CLINICAL FEATURES

The clinical features of depression vary quite widely in later life.

Thought content symptoms

Thought content symptoms include:

Neurovegetative symptoms

Neurovegetative symptoms include:

Behavioural symptoms

Other symptoms

Crying is an uncommon symptom in depression, but older people with depression may become overly distressed to seemingly minor life occurrences where previously they would have been quite stoical. The older person may also display excessively ‘needy’ or dependent behaviour. The mental health worker needs to distinguish between dependent behaviour as a manifestation of a lifelong personality style or dependent behaviour as a result of psychological regression in depression.

Another clinical feature to be aware of is ‘smiling depression’. The socially ingrained habit of many older people of being polite, pleasant and smiling, particularly on initial interactions with people, can mislead the inexperienced mental health worker into thinking the older person could not possibly be depressed (Neville & Byrne 2009). Some older people deny feeling depressed, even though they have many other symptoms of major depression.

COMORBIDITY

Depressive symptoms often coexist with vascular dementia and vascular cognitive impairment and are common in the mild and moderate stages of dementia. It is frequently reported that depression is an early feature of dementia with the suggestion that the neurodegenerative changes in the ageing brain lead first to late-onset depression and then to dementia. Depression and cognitive impairment (usually dementia) are risk factors for the development of delirium and a significant number of older people with delirium (up to 25%) have undiagnosed dementia (Fick et al 2002).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

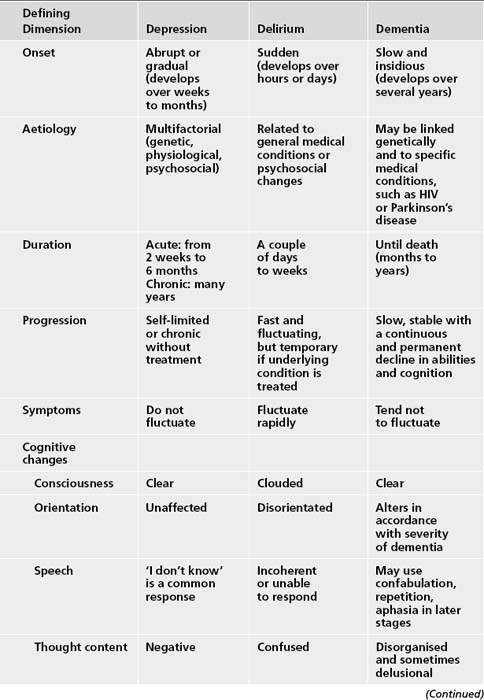

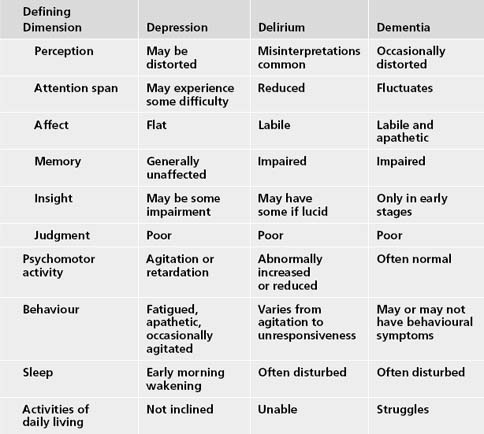

A common feature of depression, dementia and delirium is that they are all underrecognised and undertreated, and differentiating between these three syndromes is sometimes difficult. Table 20.1 sums up some of the key differences.

Other common disorders that are easily mistaken for depression include anxiety, Parkinson’s disease and the excessive sedation caused by certain medications or combinations of medication (polypharmacy). Cancer and chronic infections may present in a similar manner to depression. People who have suffered a stroke are often tearful and emotional, but this emotionality should not be confused with depression. Of course, stroke is commonly complicated by depressive disorder.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree