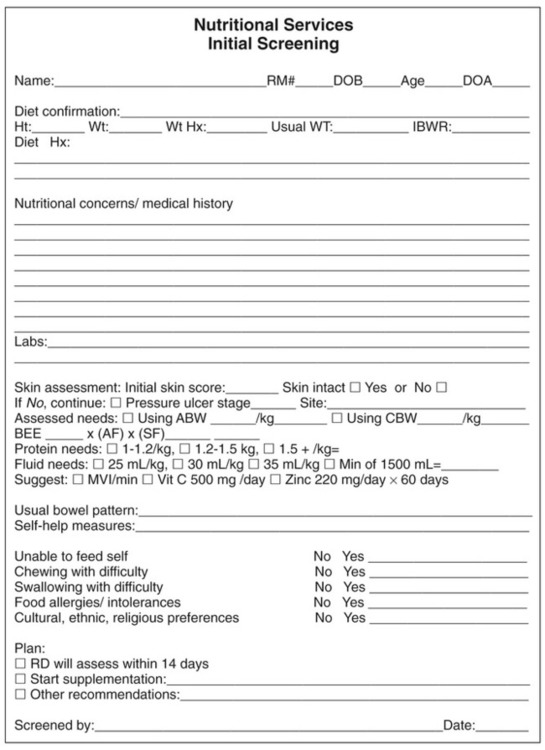

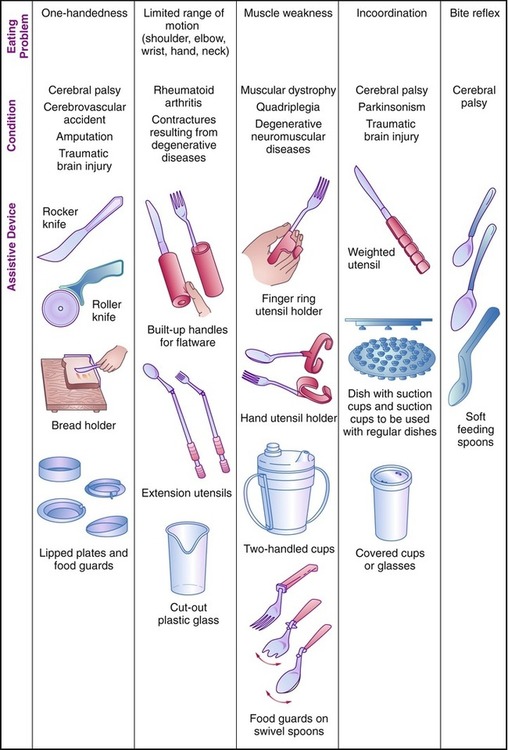

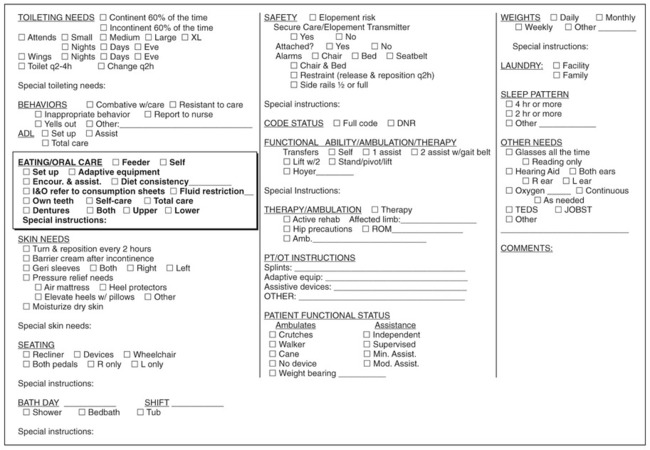

After completing this chapter, you should be able to: • Discuss the differences in acute care versus long-term care settings. • Describe patient risk factors for poor nutritional status. • Identify risk factors for skin breakdown. • Discuss institutional meal service concerns. • Discuss different types, methods, and uses of nutritional support. • Identify common drug and food interactions. • Describe differences in nutrition care between palliative and curative care. In an institutional setting, nutritional status needs to be assessed within 24 to 72 hours depending on written protocol of the institution. An eating skills assessment needs to be determined (see sample form in Figure 15-1). The anthropometric measurements of height and weight are essential to this assessment process. Determining nutritional needs for kcalories, protein, and fluids all require an accurate weight and height measurement. Having height and weight allows for calculating body mass index (BMI) (see Chapter 6 and Appendix 9). If a person is obese, the nutritional needs may be based on adjusted or corrected body weight, which is a calculation aimed at the recognition that adipose tissue has lower nutritional needs than lean muscle tissue. Using actual body weight for an obese individual can overestimate nutritional needs. One simple method of determining ideal body weight (IBW) is the following: • For women, 100 lb for the first 5 feet, and 5 lb for each additional inch • For men, 106 lb for the first 5 feet and 6 lb for each additional inch With critical illness there is often the unique issue of hypermetabolism and acute phase response inflammation leading to biochemical changes. For example, the ferritin level is raised in children with septic shock. This is associated with poorer health outcomes (Garcia and colleagues, 2007). Poor nutritional status can lead to increased risk of infection, but infection also can lead to poor nutritional status. This is due, in part, to a negative nitrogen balance with enhanced breakdown of protein found with inflammation. Infection also can reduce appetite and cause reduced food intake. With the protein catabolism found in a hypermetabolic state, muscle wasting can develop. Supplementation of the diet with the amino acids cysteine, threonine, serine, aspartate-asparagine, and arginine has been found to help spare body protein catabolism during infection (Breuillé and colleagues, 2006; Mansoor and colleagues, 2007). Another amino acid, lysine, may be beneficial to improve immunity, especially if there is a low intake such as with a vegetarian diet or one that is primarily wheat based (Kurpad, 2006). An extra 20% to 25% of the recommended nutritional needs for kcalories and protein intake may be needed for most infections. However, based upon length of hospitalization, evidence suggests that the most severely ill persons may not benefit from meeting all of their calculated nutrient needs while in the intensive care unit (ICU). Those who had an intake greater than or equal to 82% of assessed nutritional needs were found to require an increased hospital stay twice as long as those who had a lower intake (Hise and colleagues, 2007). This may be due to the difficulty in accurately assessing needs. The use of indirect calorimetry using metabolic charts (see Figure 4-3) to measure intake and output of gases through breathing is the most reliable method but is often not available or not appropriate for a given person, such as someone who uses oxygen. Avoiding overfeeding is particularly important for a malnourished person to prevent the refeeding syndrome and to allow weaning from ventilators. Determining nutritional needs for kcalories is based on mathematical calculations. The available equations may not be correct for a given individual. Of the available mathematical formulas, the Harris-Benedict (Box 15-1) is most likely to be accurate for adults but has a high level of inaccuracy in up to 39% of hospitalized patients (Boullata and colleagues, 2007). The resulting number of the Harris-Benedict equation is then multiplied by an activity factor and injury factor as appropriate. Clinical judgment may be needed to determine individual needs. It has been found that multiplication by an activity factor may lead to overfeeding of patients on controlled ventilation (Hoher and colleagues, 2008). Other situations of potential error in overestimating kcalorie needs with the Harris-Benedict equation are with obese persons with trauma or burns. Indirect calorimetry estimated 21 kcal/kg for such individuals, less than expected. This reinforces the concept that a hypocaloric regimen may be beneficial for ICU patients. Use of an injury factor of 1.2 with the Harris-Benedict equation may overestimate calorie needs (Stucky and colleagues, 2008). Even lower kcalorie intakes have been observed in medical ICU patients with resulting improved outcomes at approximately 9 to 18 kcal/kg/day (Krishnan and colleagues, 2003). For children the Schofield-HW equations for resting energy expenditure (REE) studies have the greatest accurate application (Rodríguez and colleagues, 2002). For children with significant burns, it is advised that indirect calorimetry measurements (see Figure 4-3) be used to determine kcalorie needs (Suman and colleagues, 2006). Plasma concentrations of antioxidant micronutrients have been found to be low during critical illness and infections. This has been attributed to various causes, including loss of body fluids, poor diet, provision of intravenous (IV) fluids, and a systemic inflammatory response that causes micronutrients to leave plasma and enter body cells. Three antioxidant nutrients have demonstrated clinical benefits during critical illness: selenium, glutamine, and the omega-3 fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), in addition to various trace minerals (Berger and Chioléro, 2007). The degree of selenium deficiency has been found to correlate with disease severity (Manzanares Castro, 2007). Magnesium deficiency has been found to commonly occur in critical illness. It is associated with a higher mortality and worse clinical outcomes in an ICU setting. Magnesium deficiency has been directly implicated in hypokalemia (low serum potassium), hypocalcemia, tetany (muscle spasms, cramps, and convulsions resulting from altered calcium metabolism), and dysrhythmia. The diagnosis is difficult to make because of limitations of serum magnesium assessments (Tong and Rude, 2005). Cardiac cachexia is characterized by inflammation and a hypermetabolic state. There is some evidence that nutritional supplements containing selenium, vitamins, and antioxidants may be beneficial with this condition. The goals with cardiac cachexia include shifting from a catabolic state to an anabolic state, reducing free radicals through increased antioxidant intake, reducing inflammation, and as needed achieving tight glycemic control with intensive insulin therapy (Meltzer and Moitra, 2008). This may require nutritional support to achieve the kcalories needed to promote an anabolic state (see later section). Nutritional supplements that have been regularly used in surgical and critically ill persons usually include arginine, other proteins, and omega-3 fatty acids. However, for the critically ill there is controversy due to potential for increased mortality. It is thought excess arginine may increase nitric oxide production and lead to worsened health in a person who has a critical illness (Calder, 2007). The increased need for kcalories in a hypermetabolic state is related to hormonal imbalances. Stress hormones need to be countered by an increased level of insulin. This can be achieved through increasing carbohydrate and kcalorie intake. Because of the increased production of stress hormones, elevated blood glucose levels tend to occur. Achieving tight control of glucose levels by aggressive insulin therapy has been shown to reduce morbidity in critically ill individuals (Andreelli, Jacquier, and Troy, 2006). Diabetes is a common chronic health condition, found in almost 10% of hospitalized persons (Russell and colleagues, 2005). Tight blood glucose management in an ICU hospital setting has been associated with significant reduction in kidney damage, reduced need for mechanical ventilation, and earlier discharge, thereby lowering hospital costs (Van den Berghe and colleagues, 2006). Managing blood glucose levels can be challenging in a hospital setting. Issues of a hypermetabolic state with reduced appetite and other factors can cause blood glucose levels to be erratic. Hypoglycemia that may occur has been found to be primarily an issue of excess insulin administration in relation to reduced carbohydrate intake (Hess-Fischl, 2004). Hypoglycemia needs to be avoided for optimal health outcomes. Available technology also can play an adverse role in attempts to aggressively manage blood glucose. Capillary blood glucose level as measured by finger stick has been found to be inaccurate in critically ill ICU patients and does not meet criteria of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). The actual cause of this is not known. It may be the technique used by staff in performing finger-stick blood glucose measurements. It is advised that finger-stick measurements should be used with great caution in protocols of tight glycemic control (Critchell and colleagues, 2007). There is limited evidence on what constitutes the optimal diet for hospitalized persons with diabetes (Swift and Boucher, 2006). There is no one diet that works for everyone with diabetes, and because it is now recognized that sugar and starch have identical effects on blood glucose levels, the avoidance of sugar is not necessary. Increasingly hospitals are providing consistent carbohydrate in the meal-planning system that accounts for the total carbohydrate content of the meals. For the person who is not taking insulin, the goal is to test postprandial glucose levels to verify carbohydrate tolerance and adjust intake or diabetes medications as needed. To utilize carbohydrate counting (see Chapter 8), the physician or provider must know how to prescribe insulin based on an insulin to carbohydrate ratio (see Chapter 8), and insulin needs must then be coordinated with actual carbohydrate intake of the hospitalized individual. For the hospitalized individual with diabetes who will be going home, education on diabetes is important. All nursing staff should know how to reinforce diabetes education as provided by the registered dietitian and/or diabetes educator. A performance-based approach that staff nurses can use is C-O-U-N-T C-A-R-B-S: A 10-Step Guide to Teaching Carbohydrate Counting. It has been shown that nurses who reinforce practical guidelines for persons with diabetes produce better behavioral outcomes than the didactic strategies commonly used in hospitals at present (Buethe, 2008). Persons undergoing surgery should optimally have good nutritional status. Those with malnutrition undergoing surgery have increased risk of postoperative complications, especially impaired wound healing. Albumin level less than 3.5 mg/dL has been associated with postoperative complications and longer hospital stays such as found with cancer surgery (Lohsiriwat and colleagues, 2008). Normal levels of albumin, reflective of good protein status, good nutritional intake of vitamins and minerals, especially vitamin C and zinc, optimal hydration status, and good blood glucose management are all important for good wound healing, whether from surgery or other causes. A relatively frequent problem after surgery is neuropsychiatric problems. Vitamin B12 deficiency has been found to be one cause of cognitive changes following general anesthesia (El Otmani and colleagues, 2007). The exudate of burns results in fluid loss and significant losses of protein. Albumin and prealbumin levels need to be followed to ensure adequate protein intake. Persons with burns average a need of about 5000 kcal/day during the acute phase of the burn injury. Other nutrients affected by the fluid loss at burn sites include zinc and copper, both of which are necessary for healing. Even at intakes three times the Dietary Reference Intake (DRI), the mean plasma concentrations of zinc and copper have been found to remain low (Voruganti and colleagues, 2005). Fluid intake also needs to be increased during the healing of burns to compensate for insensible fluid losses. Enteral feeding with L-arginine supplementation with early stage of burn helps to decrease adverse levels of nitric oxide production (Yan and colleagues, 2007). Glutamine may be of additional value. In addition to the need for zinc and copper, supplements of vitamins A and C are advised to promote skin healing of burn areas (Grau Carmona, Rincon Ferrari, and Garcia Labajo, 2005). There is some evidence of a nutritional component in neurologic damage associated with brain injury. Excess zinc has been implicated in the neuronal damage and death that follow traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Levenson, 2005). Vitamin B3 has shown some therapeutic potential for the treatment of TBI, with improved working memory found in an animal study (Hoane, Akstulewicz, and Toppen, 2003). Hyponatremia is a frequently observed electrolyte abnormality in persons with central nervous system disease. A high rate of hyponatremia after TBI has been observed. Correction may result with increased intake of salt, but in severe cases hydrocortisone treatment is needed (Moro and colleagues, 2007). Once AIDS has developed, a hypermetabolic state ensues, promoting muscle wasting similar to other hypermetabolic conditions. In advanced HIV-1 infection lower albumin and inflammation are both found with lower serum selenium levels. It was found as serum albumin increases, serum selenium increases as well (Drain and colleagues, 2006). This helps demonstrate the importance of good protein status. Adequate kcalories are needed to maintain positive nutritional status. However, kcalorie needs may be as high as 3500 kcal or more per day because of a fever from an opportunistic infection. A variety of factors interfere with meeting this goal. Fluid and electrolyte disorders such as diabetes insipidus, salt-wasting syndrome, and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) can alter fluid goals. Such conditions have been found within 3 days after surgery for brain tumors. In one review, diabetes insipidus was found to be the most frequent electrolyte disorder after surgery for central nervous system tumors. The salt-wasting syndrome and SIADH requires close monitoring of plasma sodium and fluid intake because of the risk of hyponatremia (Segura Matute and colleagues, 2007). Factors such as bone loss and a shortening of the spinal column during later years indicate the need for current height measurement rather than relying on reported measurements from younger years. Height is frequently difficult to determine because of kyphosis (hunched shoulders), although knee height can be used to estimate true height (or arm span measurement (see Figure 1-8, C). Monitoring weight to prevent unintended weight loss or excess weight gain is vital. Significant weight loss or gain is a change in weight equal to or greater than 5% in 30 days, 7.5% in 90 days, or 10% weight in 180 days. Chronic weight loss over this time period, even if not of a significant amount, also can indicate a goal of increased kcalorie provision needs. A significant weight loss during a 6-month period has been found to be associated with a nearly twofold increase in mortality (Yamashita and colleagues, 2002). To promote adequate oral intake of a long-term care resident requires adequate supervision and encouragement to eat. The optimal average amount of staff time required to provide the interventions for the goal of good oral intake was found to be 42 minutes per person per meal and 13 minutes per person per between-meal snack. In contrast, usual care was found to be on average 5 minutes of assistance per person per meal and less than 1 minute per person per snack (Simmons and colleagues 2008). Residents with dementia-related disorders are more prone to weight loss and malnutrition. Close to 70% in one study were at risk of malnutrition. Food service factors, including timing of meals; difficulty manipulating dishes, lids, and food packages; and therapeutic diets, were all significantly associated with risk of malnutrition (Carrier, West, and Ouellet, 2006). When a person is dehydrated, immobilized, receiving narcotic analgesics for pain, or has altered gastrointestinal function, constipation can lead to bowel obstruction. Bowel movements are needed at least 2 to 3 times weekly to prevent bowel obstruction. Increased fluids and fiber are preferred over laxative use, but the latter also may be required to maintain normal bowel function. A cake made with oat fiber was found to be well accepted and beneficial. Laxatives were able to be reduced by about 60% in the fiber group (Sturtzel and Elmadfa, 2008). Prune juice and prunes (dried prunes) are helpful in bowel management. This is believed to be due to the naturally high content of sorbitol but may also be due to phenolic compounds (Stacewicz-Sapuntzakis and colleagues, 2001). Development of pressure ulcers in the hospital has been estimated to affect 10% of admissions, with elderly patients at the highest risk (Harris and Fraser, 2004). Even children can have skin breakdown. The prevalence of skin breakdown in acutely ill hospitalized children approaches one in four, although the majority of such occurrences are stage I (Suddaby, Barnett, and Facteau, 2005). Home care nurses also may have to manage pressure ulcers. More than half of the nursing home population is incontinent of urine or feces, which is a risk factor for skin breakdown. Close monitoring and cleansing with a pH-balanced cleanser and moisture barrier can help maintain skin integrity among persons with incontinence (Zimmaro and colleagues, 2006). Malnutrition is a risk factor for skin breakdown. One study of older persons found intake of less than or equal to 75% of meals was related to risk along with iron deficiency anemia, inflammation, and low levels of albumin, retinol, selenium, and zinc (Raffoul and colleagues, 2006). Nutritional deficiencies of a variety of vitamins and minerals may go undetected. For this reason, a multivitamin supplement is often recommended for prevention of skin breakdown, especially when there is poor nutritional intake. • Malnourishment or less than 75% required intake of solids • Dehydration or less than 75% assessed fluid needs • Stage I: A nonblanchable area on the skin (does not turn white when pressure is applied). For persons with dark skin, there may be discoloration, edema, or thickening of the skin. • Stage II: An open sore or blister that involves the epidermis and/or dermis layers. • Stage III: Damage to the subcutaneous region is present, and a crater forms. • Stage IV: Damage down to the muscle and bone, and sometimes tendons, occurs. • Suspected Deep Tissue Injury: Discolored intact skin or blood-filled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure and/or shear. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, firm, mushy, boggy, warmer, or cooler compared with adjacent tissue. • Unstageable: Full-thickness tissue loss in which the base of the ulcer is covered by slough (yellow, tan, gray, green, or brown) and/or eschar (tan, brown, or black) in the wound bed. Other common types of chronic skin ulcers include ischemic ulcers, venous ulcers, and neuropathic ulcers. Pressure relief should be provided for both pressure ulcers and neuropathic ulcers. Ischemic ulcers require revascularization. Individuals with venous ulcers need adequate edema control to promote healing (Takahashi, Kiemele, and Jones, 2004). Pressure and venous ulcers are common in the elderly population. For wound healing a supplement of 500 mg of vitamin C and 220 mg of zinc sulfate (50 mg of elemental zinc) has been standard protocol, especially for more-severe skin breakdown (stage III or IV). However, excess intake of zinc was found to delay the rate of wound healing (Lim, Levy, and Bray, 2004). It also is known to reduce copper levels and can cause a severe form of anemia due to low copper levels. Many enzymes required for protein synthesis of new skin are dependent on copper as well as zinc. Consequently, large doses of zinc are being used less often or for short periods of time. The upper limit of safety for zinc is 40 mg/day (see the back of the book). The DRI for zinc for persons greater than 70 years of age is 8 mg for women and 11 mg for men. It may be better protocol to use 110 mg zinc sulfate (25 mg elemental zinc). Clinical studies also have shown the beneficial effects of trace elements such as boron and manganese in wound healing (Chebassier and colleagues, 2004). With regard to macronutrient needs for healing, an increased amount of protein is advised. The guidelines are a range of 1.2 to 2.0 g of protein per kilogram of body weight depending on the severity. Along with standard protocol, the amino acid arginine appears to be of importance in healing stage III and IV pressure ulcers (Frias Soriano and colleagues, 2004). However, there is concern that L-arginine could be detrimental in an inflammatory state (Stechmiller and colleagues, 2005), and it is advised in large doses only in critically ill persons under carefully monitored study conditions (Wilmore, 2004). In a small study, supplementary arginine (9 g), vitamin C (500 mg), and zinc (30 mg) was found to significantly improved the rate of pressure ulcer healing (Desneves and colleagues, 2005). A higher kcalorie intake of 30 to 35 kcal/kgBW is generally needed for healing. However, in elders with pressure ulcers no increase in energy expenditure was found, and a range of 25 to 30 kcal/kgBW/day is suggested (Dambach, and colleagues 2005). For the malnourished elder, an increased number of kcalories will be needed to promote a gain of body weight, important for wound healing. A study conducted in Turkey found honey dressings to be effective and practical. The use of honey dressings was four times more effective in promoting healing of stage II and III pressure ulcers compared with a commercial dressing (Yapucu Güne Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) affects millions of persons and is particularly common in the long-term care setting. As reviewed in Chapter 4, the act of swallowing seems simple but in fact is extremely complex with multiple muscles needing to be coordinated. Good neuromuscular control is essential for safe swallowing to prevent choking and aspiration pneumonia. A person with decreased cognition may need to be reminded to chew and swallow. Elderly persons with dysphagia need food that requires little or no chewing, is easy to swallow, and is still appealing to eat, both visually and in terms of taste. The production of a sufficient amount of saliva is indispensable for good chewing. The addition of lemon to meals has been shown to invoke saliva production. Adding fluid to foods can significantly reduce the amount of chewing and total muscular work. Adding fluid to breakfast cake type of foods is particularly beneficial for persons with low saliva production (van der Bilt and colleagues, 2007). Buttering the food can reduce the amount of chewing needed before swallowing. This is especially helpful for dry foods such as cake and toast (Engelen, Fontijn-Tekamp, and van der Bilt, 2005). Commercial thickeners come in two main forms. One is based on the gum type of fibers, the other is a form of starch. All thickeners have been found to suppress the flavors of beverages and give slight off-flavors (bitter, sour, metallic, or astringent). Starch-based thickeners impart a starchy flavor and grainy texture, whereas gum-based thickeners give added slickness to the beverages. Some beverages do not lend themselves well for thickening, causing lumps to form. Individual decisions must be made about which characteristics are more negative (e.g., slick versus grainy texture) for specific patients (Matta and colleagues, 2006). Although there are commercially available prethickened liquids, there are a number of issues yet to be resolved. One impact on thickness is the amount of time it takes to consume a thickened liquid. Time and temperature have bearing on how well the thickened liquid maintains its consistency for the starch-based thickeners. The gel-based thickeners maintain their thickness regardless of time or temperature, although their use may be challenging to meet adequate thickness criteria. Simply Thick, the gum-based thickener, typically produced samples that were the least viscous, but they maintained a more consistent level of thickness over time (Garcia and colleagues, 2008). Commercial nectar- and honey-consistency beverages were found to be significantly more viscous at various temperatures compared with their individually thickened counterparts. Commercially thickened beverages at nectar and honey consistencies were almost always more viscous, typically more like syrup consistency, than the National Dysphagia Diet Task Force–defined standards (Adeleye and Rachal, 2007). See Table 4-1 regarding considerations for food texture modification. All disciplines working in a long-term care setting need to develop care plans. This is the means by which all members of the health care team communicate with one another. Care plans are developed within 14 days initially upon admission and are reviewed at least quarterly and annually through care plan meetings that include the resident, registered nurse (RN), RD, social work, activities, and others as appropriate such as the occupational therapist (OT) and physical therapist (PT). Nutritional assessments identify the nutritional areas of risk, and a nutritional care plan is developed using measureable objectives and goals with specific care communicated with all nursing staff. The CNAs need to know their daily role with pertinent nutritional goals such as may be written on CNA resident care cards (Figure 15-2). Food will be more appealing if it is served at the proper temperature and as soon as possible after preparation to maintain palatability. It may be necessary to cut meat into bite-size pieces, butter bread, and open containers if the individual is unable to perform those tasks independently because of weakness or pain from arthritis, for example. Certain adaptive equipment may be needed to help maintain independence in eating. Plates and bowls can be stabilized with rubber pads (Dycem mats) and suction cups. Soup can be more easily managed if poured into a cup. Foam-covered spoon and fork handles are useful for individuals who have lost some ability to handle silverware easily (Figure 15-3). The delivery of medical nutrition therapy in a health care setting revolves around basic institutional diets. Tables 15-1 and 15-2 list information on common diets used and foods allowed and omitted. Some differences exist from one health care facility to another in the foods permitted in each category, as well as in the number of kinds of diets. When an individual is admitted to a facility, the health care provider will select the type of diet, often with input from a staff dietitian. In some health care facilities the dietitians are responsible for ordering diets. Diets may be changed if and when the individual’s condition makes it desirable. The nursing staff often identifies and communicates needed changes in the person’s diet. Particularly in long-term care settings, in which the facility is considered the person’s home, resident rights may dictate discontinuing diet restrictions. Table 15-1 Progressive Basic Hospital Diets

The Nutrition Care Process in the Health Care Setting

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF MEDICAL NUTRITION THERAPY IN A HEALTH CARE SETTING?

WHAT ARE ISSUES OF ACUTE CARE?

CRITICAL ILLNESS

DIABETES

SURGERY

BURNS

TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY

HIV AND AIDS

FLUID NEEDS IN CRITICAL CARE

WHAT ARE LONG-TERM HEALTH CARE ISSUES?

HOW IS THE OLDER ADULT’S NUTRITIONAL STATUS ASSESSED?

WEIGHT MONITORING

BOWEL MANAGEMENT

PRESSURE AND OTHER SKIN ULCERS

and E

and E er, 2007). This approach is not advised for an institutional setting in the United States, but may have implication in a situation where a commercial dressing is not readily available. However, a commercial honey-based dressing is now available.

er, 2007). This approach is not advised for an institutional setting in the United States, but may have implication in a situation where a commercial dressing is not readily available. However, a commercial honey-based dressing is now available.

DYSPHAGIA

CARE PLANS

WHAT ARE INSTITUTIONAL MEAL CONCERNS AND CONSIDERATIONS?

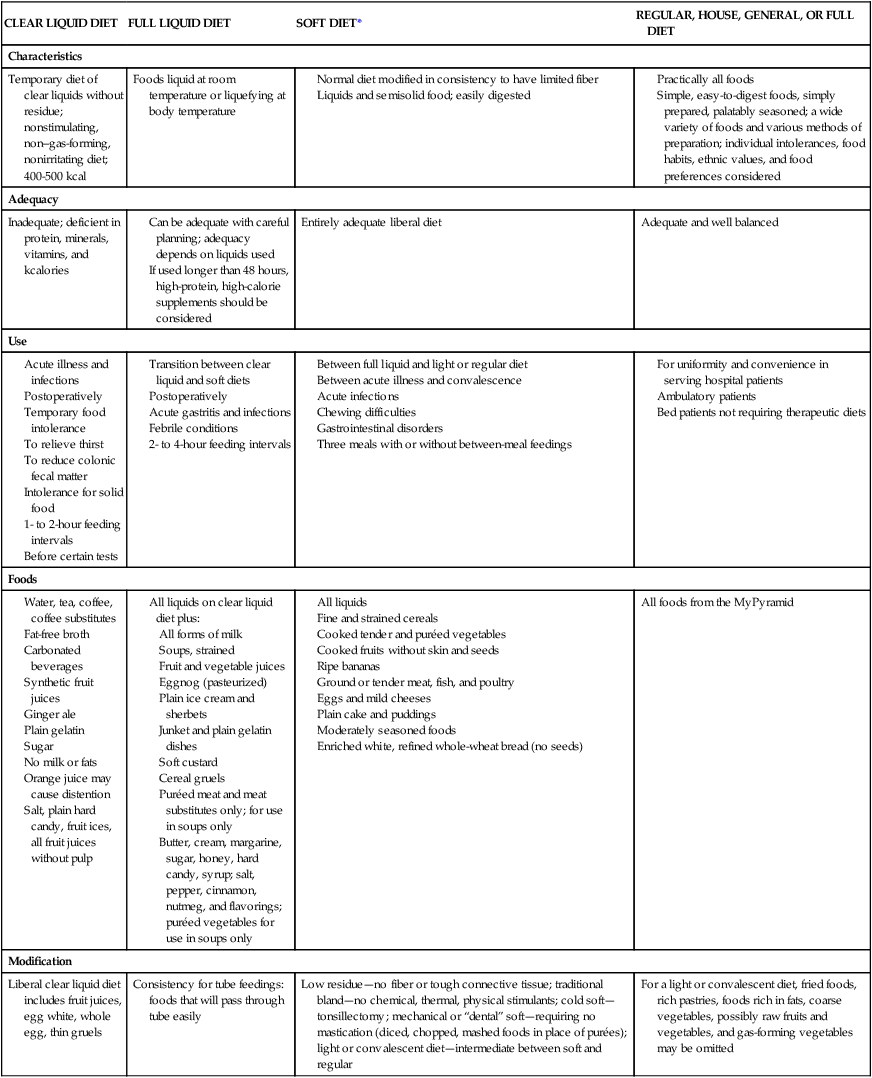

CLEAR LIQUID DIET

FULL LIQUID DIET

SOFT DIET*

REGULAR, HOUSE, GENERAL, OR FULL DIET

Characteristics

Temporary diet of clear liquids without residue; nonstimulating, non–gas-forming, nonirritating diet; 400-500 kcal

Foods liquid at room temperature or liquefying at body temperature

Adequacy

Inadequate; deficient in protein, minerals, vitamins, and kcalories

Entirely adequate liberal diet

Adequate and well balanced

Use

Foods

All foods from the MyPyramid

Modification

Liberal clear liquid diet includes fruit juices, egg white, whole egg, thin gruels

Consistency for tube feedings: foods that will pass through tube easily

Low residue—no fiber or tough connective tissue; traditional bland—no chemical, thermal, physical stimulants; cold soft—tonsillectomy; mechanical or “dental” soft—requiring no mastication (diced, chopped, mashed foods in place of purées); light or convalescent diet—intermediate between soft and regular

For a light or convalescent diet, fried foods, rich pastries, foods rich in fats, coarse vegetables, possibly raw fruits and vegetables, and gas-forming vegetables may be omitted

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Nutrition Care Process in the Health Care Setting