Anthea Tinker, Simon Biggs, Jill Manthorpe

The Mistreatment and Neglect of Frail Older People*

Evidence about the abuse, mistreatment, and neglect of frail older people has been emerging over the past decades. In this chapter, we first examine the development of concern, definitions, prevalence rates, and risk factors. We then discuss ways in which the risks of elder abuse may be identified in clinical practice as well as in public health strategies and consider prevention and responses. We write from the perspective of developments in the United Kingdom and draw mainly on studies in the wider European and North American context. However, the publication of “Hidden Voices” by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 20021 followed by the WHO European report on preventing elder mistreatment in 20112 has revealed widespread recognition of this problem internationally. There is scope for continuing to draw lessons from cross-national perspectives, while recognizing differences in service and legal provisions as well as cultural interpretations of abuse between countries. Although there are lessons to be learned from child abuse, simplistic parallels should not be drawn. For example, there are dangers in interventions narrowly focused on the protection of older people (although safeguarding their rights is of growing importance) if they are ageist in philosophy or undermine autonomy and rights in civil and criminal law. The European Convention on Human Rights, now incorporated into U.K. domestic law, offers an important counter to these dangers, as does the growing emphasis on empowerment. This suggests the importance of being aware of overlaps with cases of domestic violence3 and the acknowledged difficulty of working within long-standing family conflict. Elder abuse, however, is not confined to family or domestic settings, and clinicians have responsibilities for the well-being of their patients in hospitals and in long-term care facilities.

Historical Development

Early concerns about mistreatment of older people were raised by doctors who detected a parallel with child abuse and placed the issue in the wider context of the care of older people both in their own homes and in long-term care facilities, emphasizing the importance of good geriatric practice.4,5 However, an evidence base was slow to develop despite notable exceptions.6,7 In its absence, abuse was linked to concerns about the stress placed on family caregivers supporting older people, particularly those with dementia. Policy in many countries has drawn on developments from the United States, which advocates the creation of local protocols when abuse is suspected or revealed. In the United Kingdom, policy developments have also responded to professional and pressure group concerns that elder abuse has been insufficiently resourced and prioritized.8

Definitions

The WHO9 defines elder mistreatment as “a single or repeated act or lack of appropriate action occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust, which causes harm or distress to an older person” (p. 6). The U.S. National Research Council10 supplies an operational definition that includes “intentional actions that cause harm or create a serious risk of harm (whether or not harm is intended) to a vulnerable elder by a caregiver or other person who stands in a trust relationship to the elder” and “failure by a caregiver to satisfy the elder’s basic needs or to protect the elder from harm” (p. 40).

Box 112-1 provides definitions of types of mistreatment, including both behavior and effect. The terms elder abuse, mistreatment, and neglect refer to the ill-treatment of an older person (usually defined as older than 60 years) by acts of commission or omission. They may occur in domestic settings (the older person’s own home, a relative’s home, or supported housing), in long-term care facilities (assisted living, nursing homes, and hospitals), or in the community. Some kinds of behavior are criminal acts, such as assault and theft; other forms, such as verbal abuse, the restraint of someone who is aggressive, or apparent overmedication, may be more contingent on particular circumstances. Definitions are important, but multiple terms are used and sometimes overlap. For example, abuse and neglect generally refer to behavior within a relationship connoting trust. This distinguishes actions by those closely linked to the older person (such as family members) or others in positions of responsibility for their care (such as nursing staff or family physicians) from actions by strangers. These boundaries are not always clear; for example, electronic fraud is a growing crime that may also fall under the definition of abuse when the older person is vulnerable because he or she has dementia. A recent trend has been to broaden understanding of abuse to include resident-on-resident abuse in long-term care facilities,11 the characteristics of abusive environments,12 contextual factors permitting abuse,13 and the relationship of abuse to caregiver stress or characteristics.14

Different Types of Abuse and Neglect

There is now widespread agreement about five categories of abuse: physical violence; psychological abuse, often measured by persistent verbal aggression; financial abuse; sexual abuse; and neglect.15 However, there remains very limited information on how often these types of abuse occur together and whether they are separate phenomena, but the research suggests that they both occur singly and in combination and that explanations for the abuse, and therefore the factors relevant to risk, may vary accordingly. The U.K. prevalence study16,17 distinguished between forms of abuse that are interpersonal and of an intimate nature, financial forms, and neglect. Whether or not a common label and tendency to a common response are useful requires further research. The U.K. study used a series of behavioral definitions of abuse to take frequency and severity into account, and these definitions may be of greater use to professionals than those intended for policy makers. Prevalence studies are now available from a number of countries in Europe, North America, and East Asia, but comparisons should be made with caution. For example, social abuse and isolation were identified as an additional category by some East Asian studies.18

Vulnerability of Frail Older People

In the context of elder abuse, vulnerability may be related to physical and mental frailty, as well as disability. Socioeconomic factors such as low income, minority ethnic background, and poor housing have been associated with enhanced risks.17 The majority of prevalence studies have collected data from older people living in community settings. Evidence from other locations about abuse and neglect tends to arise from public inquiries, inspection reports, and case studies, for example, the major U.K. inquiry into events at Mid Staffordshire NHS hospital where hundreds of older patients’ care was poor, abusive, and neglectful.19

Residents of nursing homes or other long-term care facilities may be deemed vulnerable or at risk by virtue of their increased disability or their living situations. Professionals are particularly likely to have contact with these groups of older people, who, because of their physical and/or mental impairments, are least able to protect themselves. However, while there are various discussions about individual risks, it may also be worth thinking about vulnerable situations. This means analyzing the context rather than personal vulnerability. For example, not all people with dementia are at risk, but those who are may have few people to safeguard their best interests and may be easy prey for the unscrupulous.20

Prevalence and Incidence

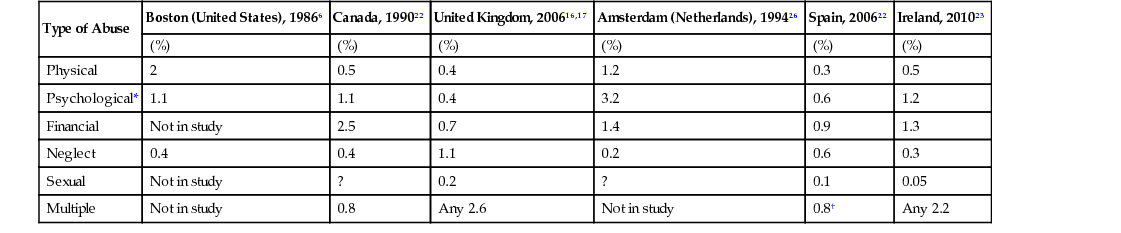

Table 112-1 shows prevalence (in percentages) of elder mistreatment in North America, Canada,21 the United Kingdom, Ireland, Amsterdam (the Netherlands), and Spain.22 Studies have also taken place in Spain, the Czech Republic, Finland, Sweden, and Germany. The Spanish study22 is one of national community prevalence, indicating a figure of 0.8% reported by older people but 4.5% by caregivers. Some studies of community prevalence in North America were based on telephone interviews.6 The U.K. survey was based on individual face-to-face interviews with people aged 66 and older.16 Overall in this survey, 2.6% of people aged 66 and older living in private households reported that they had experienced mistreatment involving a family member, close friend, or care worker (i.e., those in a traditional expectation of trust or trust relationship) during the past year. When this 1-year prevalence of mistreatment was widened to include incidents involving neighbors and acquaintances, the overall prevalence increased to 4.0%. The Irish study23 found less neglect but more psychological abuse than the U.K. study. Data from Hong Kong24 and mainland China25 are also available, reporting higher instances of mistreatment than other studies. Variation between national studies cannot be taken to indicate ethnic or cultural differences in prevalence because standardized measurements were not used.

TABLE 112-1

Prevalence of Elder Abuse

| Type of Abuse | Boston (United States), 19866 | Canada, 199022 | United Kingdom, 200616,17 | Amsterdam (Netherlands), 199426 | Spain, 200622 | Ireland, 201023 |

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Physical | 2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Psychological* | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 1.2 |

| Financial | Not in study | 2.5 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| Neglect | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Sexual | Not in study | ? | 0.2 | ? | 0.1 | 0.05 |

| Multiple | Not in study | 0.8 | Any 2.6 | Not in study | 0.8† | Any 2.2 |

One particular difficulty for studies using the general population is that people who are highly reliant on another person for activities of daily living, and particularly people who have severe cognitive impairment, are unable to participate, except by proxy. In the U.K. and Spanish studies, people with severe dementia or otherwise unable to take part were excluded from the research. In the Dutch study, nonresponse was relatively high for those with mental and physical incapacity (although all were living independently).26 Yet it is precisely these people whom practitioners might identify as most vulnerable or at risk.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree