Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), defined as lacking expression of the estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2, comprises approximately 15% of incident breast cancers and is over-represented among those with metastatic disease. There are several biologically distinct subtypes within TNBC. Although the incidence of BRCA mutations across all subsets of breast cancer is low, BRCA mutations are more common among those with TNBC and may have therapeutic implications. The general principles guiding the use of chemotherapy and radiation therapy do not differ dramatically between early-stage TNBC and non-TNBC.

Key points

- •

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) lacks expression of the estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2 by clinical assays.

- •

Although more commonly associated with the basal-like subtype of breast cancer, research assays have further dissected the biology of TNBC and have identified 6 subtypes thus far.

- •

The incidence of BRCA mutations is higher among patients with TNBC (approximately 20%) compared with those with breast cancer across all subtypes (approximately 5%).

- •

Local and systemic therapy approaches to early-stage TNBC should be similar to those of non-TNBC; however, endocrine and HER2-directed therapies are not prescribed.

- •

In the metastatic setting, the mainstay of systemic therapy to treat TNBC is cytotoxic chemotherapy; targetable pathways are currently under investigation in the preclinical setting and early-phase clinical trials.

- •

A coordinated effort between scientists and clinicians is required to develop novel therapies to treat TNBC most effectively.

Introduction: overview and scope of the problem

The management of TNBC, a disease that affects approximately 180,000 women worldwide, is challenging. Clinically defined as lacking expression of the ER, the PR, and HER2 by immunohistochemistry (IHC), TNBC comprises approximately 15% of incident breast cancers and is over-represented among those with metastatic disease. TNBC is usually high grade, more often an interval breast cancer (ie, diagnosed between screening mammograms), and, when recurrent, preferentially relapses in visceral sites, such as lungs, liver, and brain. Given the higher rates of recurrence and lack of traditional targets (such as ER and HER2), treating those with TNBC evokes anxiety on the parts of both patient and provider. This review article addresses the unique biology of TNBC, followed by a detailed discussion of state-of-the-art local and systemic treatments in the early-stage setting. Approved cytotoxics to treat advanced TNBC and the many emerging targeted agents in development to treat this aggressive disease are discussed.

Introduction: overview and scope of the problem

The management of TNBC, a disease that affects approximately 180,000 women worldwide, is challenging. Clinically defined as lacking expression of the ER, the PR, and HER2 by immunohistochemistry (IHC), TNBC comprises approximately 15% of incident breast cancers and is over-represented among those with metastatic disease. TNBC is usually high grade, more often an interval breast cancer (ie, diagnosed between screening mammograms), and, when recurrent, preferentially relapses in visceral sites, such as lungs, liver, and brain. Given the higher rates of recurrence and lack of traditional targets (such as ER and HER2), treating those with TNBC evokes anxiety on the parts of both patient and provider. This review article addresses the unique biology of TNBC, followed by a detailed discussion of state-of-the-art local and systemic treatments in the early-stage setting. Approved cytotoxics to treat advanced TNBC and the many emerging targeted agents in development to treat this aggressive disease are discussed.

Unique biology of triple-negative breast cancer

TNBC is defined clinically as lack of ER, PR, and HER2 expression by IHC (with confirmation of HER2 status by fluorescence in situ hybridization if indeterminate [2+] by IHC). According to the most recent American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guidelines, ER and PR negativity is strictly defined as less than 1% expression, as opposed to older definitions allowing up to 1% to 10% borderline ER/PR expression. In an analysis of more than 1700 breast tumors, although the majority of TNBCs (as strictly defined by IHC as <1% ER/PR expression) fall into the basal-like subtype by gene expression analysis (207/283, 73%), borderline cases (n = 48) were more commonly luminal (46%) or HER2 enriched (29%). Based on this observation, it is recommended that clinical trials aimed at enrolling women patients with TNBC/basal-like breast cancer should adhere to the American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline–recommended definition of ER/PR less than 1% when developing inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Although the basal-like breast cancer subtype has been associated with TNBC for approximately a decade, newer subtypes within TNBC are emerging. More recently, a novel molecular subtype identified as claudin-low has been characterized via gene expression of human breast tumors, a panel of breast cancer cell lines, and mouse models of breast cancer. Clinically, claudin-low breast tumors are commonly ER, PR, and HER2–negative via IHC and show a high frequency of metaplastic and medullary differentiation and an intermediate response to cytotoxic chemotherapy (between that of basal-like and luminal breast tumors). Moreover, claudin-low breast tumors have been shown to exhibit stem cell characteristics, low expression of cell-cell adhesion proteins (ie, claudin 3, claudin 4, and claudin 7), high enrichment for epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers, and low luminal/epithelial differentiation.

A group of investigators has further dissected the biology of TNBC, identifying 6 unique subsets of TNBC through gene expression analysis of more than 500 breast tumors from more than 20 independent data sets. This analysis classified TNBCs into the following clusters: 2 basal-like (BL1 and BL2), an immunomodulatory, a mesenchymal, a mesenchymal stem–like, and a luminal androgen receptor (AR) subtype. Approximately 30 TNBC cell lines were then classified into each of these categories and pharmacologically inhibited to illustrate that classification may inform therapeutic strategies. Results showed that the BL1 and BL2 subtypes, both with higher expression of DNA damage response genes, responded to cisplatin. Response to phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and Src inhibition was observed in the mesenchymal and mesenchymal stem–like subtypes, which are enriched for EMT and growth factor pathways. Finally, cell lines within the luminal AR subtype were preferentially responsive to the AR antagonist, bicalutamide—a concept that has borne out to a degree in the clinical arena. Given the apparent heterogeneity within TNBC, a 1-size-fits-all approach is no longer appropriate because clinical trials are designed for patients with TNBC. Consideration of the distinct subsets within TNBC is paramount in aiming to improve outcomes for this aggressive disease.

Association with BRCA Mutations

In addition to advances in understanding the underlying biology of TNBC, several studies have illustrated the association of TNBC with germline BRCA mutations. A recent observational study was aimed at determining the incidence of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in 77 patients with TNBC. BRCA mutations were detected in 19.5% of patients: 15.6% BRCA1 and 3.9% BRCA2 . In this cohort of patients, outcomes were superior among BRCA mutation carriers compared with wild-type patients, including 5-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) (51.7% vs 86.2%, P = .031) and 5-year overall survival (OS) (52.8% vs 73.3%, P = .225). Further confirming these findings, an integrated molecular analysis of breast carcinomas in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) reports that approximately 20% of basal-like breast tumors harbored a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, of which approximately two-thirds were germline and one-third were somatic. BRCA1 inactivation was found common among both basal-like breast cancers and serous ovarian cancers. This finding suggests shared driving events for both diseases and that therapeutic approaches (ie, use of platinums, taxanes, and inhibitors of poly-ADP-ribose polymerase [PARP]) may be guided more by molecular profile and less by tissue of origin.

Therapeutic options for early-stage triple-negative breast cancer

Although the basic principles, including surgical management, radiation therapy techniques, and decisions regarding systemic therapies, are similar between stages I to III TNBC (as defined by the TNM staging system) and endocrine and/or HER2+ counterparts, there are some nuances specific to TNBC that should be considered. In addition, there have been several provocative studies in the field of radiation therapy specific to patients with TNBC that are worthy of review.

Local Therapy/Radiation Therapy

Given conflicting retrospective studies regarding whether women with TNBC are at a higher risk of local recurrence after breast-conserving therapy (BCT) and whether they might be better served by a modified radical mastectomy (MRM), it has become accepted that either treatment paradigm is reasonable in the management of early-stage TNBC. Recent studies suggested, however, that early-stage TNBC patients may be at a higher risk for local recurrence when treated with MRM alone, omitting postmastectomy radiotherapy (RT) (ie, in T1-T2N0 patients lacking classic indications for postmastectomy RT), which warrants discussion.

In a large single-institution retrospective review of 768 women with T1-T2N0 TNBC, investigators from McGill University found a significant difference in locoregional recurrence rates (LRRs) between patients treated with BCT, MRM, or MRM plus RT. Five-year LRR-free survival rates were 96% and 90% in BCT and MRM patients, respectively ( P <.03), and MRM was the only independent prognostic factor associated with LRR (hazard ratio 2.5), suggesting that MRM alone may not be enough local therapy in these patients. A prospective trial performed in Shanghai randomized 681 women with stage I-II TNBC after MRM to chemotherapy with or without RT. Although not their primary endpoints, the investigators found a statistically significant difference in RFS and OS, favoring the group who received both adjuvant chemotherapy and post-MRM RT. Five-year RFS improved from 75% to 88% with the addition of RT, and adding RT improved 5-year OS impressively, from 79% to 90%. Although retrospective and thus subject to unintended bias, these are intriguing but hypothesis-generating data, warranting further study in a rigorous randomized controlled trial but not warranting a change in clinical practice.

Many TNBC patients receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy in hopes of becoming BCT candidates or as a means to assess in vivo response to systemic therapy. There has been a growing discussion about whether or not to omit post-MRM RT in patients with significant down-staging secondary to chemotherapy or even to modify RT field design based on response to chemotherapy. This issue is not unique to women with TNBC. Unfortunately, there are no prospective data to support this practice. Retrospective data from MD Anderson Cancer Center suggest that patients with residual nodal disease benefit from post-MRM RT, but those left with stage I/II disease after chemotherapy do not derive such a benefit. Interpretation of these findings must acknowledge, however, the limitations of subgroup analyses of patients in whom the use of RT was left to the discretion of a physician and the absence of prospective or controlled studies. In the absence of prospective data, it remains standard of care to irradiate the same fields (ie, chest wall or supraclavicular fossa, with or without irradiation of the internal mammary chain if cT3 or node positive) after neoadjuvant chemotherapy as would be done if patients had up-front surgery.

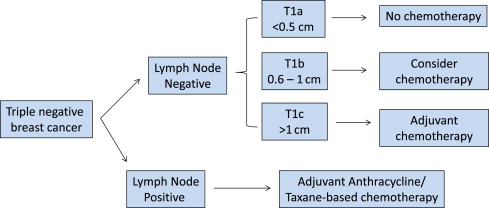

Systemic Therapy—Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Treatments and Ongoing Clinical Trials

The only opportunity for recurrence risk reduction to treat TNBC with curative intent is systemic chemotherapy, because there are currently no approved targeted treatments, like endocrine or HER2-directed therapy, to ameliorate baseline risk. As such and in compliance with guidelines put forth by the National Cancer Comprehensive Network ( www.NCCN.org ), it is common and appropriate for oncologists to prescribe anthracycline/taxane-based chemotherapy at a lower stage for TNBC compared with hormone receptor–positive counterparts. Although use of a more-aggressive regimen (ie, anthracycline/taxane as opposed to a taxane-based regimen) may be reasonable in many TNBCs, it is also true that “biology does not trump anatomy.” A small node-negative TNBC carries a low (15% or less) 5-year risk of recurrence and a proportionally lower benefit of treatment. Using tools, such as Adjuvant! OnLine, the mortality risk at 10 years for T1a/bN0 tumors is less than 10%. An observational study of more than 1000 T1a/bN0 TNBCs found excellent prognosis, with 95% remaining free of distant metastasis at 5 years and without a notable difference between those who did and those who did not receive chemotherapy. Taking this into account, a reasonable algorithm for adjuvant chemotherapy in node-negative TNBC is to offer it if tumor size is greater than 1 cm and if it is otherwise medically appropriate; a balanced discussion for 0.6 cm to 1.0 cm tumors; and no adjuvant chemotherapy in breast tumors 0.5 cm or less (T1a). As with other subtypes of breast cancer, adjuvant anthracycline/taxane-based chemotherapy is recommended in patients with lymph node–positive disease (N1 or greater), regardless of primary tumor size ( Fig. 1 ).

The principles that govern the decision to proceed with neoadjuvant versus adjuvant chemotherapy are similar between TNBC and other subtypes of breast cancer. These principles are largely driven by (1) resectability of the primary tumor and lymph nodes to achieve negative margins and (2) the ability to cytoreduce a breast cancer to facilitate breast conservation, as opposed to a mastectomy. Historically and as guided by the landmark study National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-27, chemotherapy sequenced before (as opposed to after) surgery does not seem to improve survival. Response to chemotherapy, however, in particular, achievement of pathologic complete response (pCR), can help identify those patients with better prognosis. Basal-like/TNBC has consistently been shown more sensitive to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (ie, higher pCR rates) than luminal breast cancers. Collectively, however, TNBC patients experience poorer overall outcomes compared with other breast cancer subtypes. The poorer prognosis of basal-like/TNBC has been explained by a higher likelihood of relapse in those patients in whom pCR was not achieved and has been termed, the triple-negative paradox .

Using pCR rates for patients with TNBC as an endpoint, investigators are evaluating additional chemotherapies and targeted agents in the neoadjuvant setting. A trial of interest, Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 40603 ( NCT00861705 ), is evaluating the addition of a platinum (ie, carboplatin) and/or an antiangiogenesis agent (ie, bevacizumab) to standard anthracycline/taxane-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the setting of locally advanced TNBC. Importantly, all patients in this trial are required to undergo dedicated biopsies to identify predictive markers of response. Platinum agents have been an area of investigation in TNBC based on the hypothesis of augmented sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents in dysfunctional BRCA . Although small studies have suggested high clinical responses to cisplatin in germline BRCA mutation carriers, whether this holds true in sporadic TNBC is uncertain; prospective data await the results of CALGB 40603. Results of neoadjuvant bevacizumab studies in TNBC have previously been mixed, and the addition of 1 year of bevacizumab to adjuvant chemotherapy in TNBC failed to improve invasive disease-free survival in a recently reported, large (n>2500 patients), open-label, randomized, multinational phase III trial. Anticipated results of CALGB 40603 will continue to add the understanding of the role of bevacizumab, if any, in the curative treatment of TNBC and to identify those patients who may benefit from these approaches.

Another area of active research pertains to those with residual disease—specifically, the group of patients with TNBC who do not achieve a pCR after neoadjuvant chemotherapy—in an effort to improve outcome for those at greatest risk for local and/or distant recurrence. Although scientists are actively analyzing the molecular changes in residual breast tumor after preoperative cytotoxic therapy, an ongoing randomized phase III trial is also evaluating the benefits of an intensive diet/exercise intervention or without adjuvant metronomic chemotherapy (6 months of cyclophosphamide/methotrexate) plus bevacizumab (12 months) in patients with residual disease to determine if this strategy reduces recurrence in this high-risk group.

At this point, the choice of chemotherapy regimen does not differ between TNBC and non-TNBC. Retrospective studies have suggested that much of the benefit of adjuvant anthracyclines is in the HER2-overexpressing subset of tumors; however, this finding is not universal or definitive. More recently, molecular studies suggest that the HER2-enriched molecular subtype derived the primary benefit of an anthracycline regimen (cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and 5-fluoruracil) over the classic regimen (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluoruracil); in that retrospective analysis, the basal-like subtype seemed to benefit equally from both regimens. Although intriguing, intrinsic subtyping for this purpose is not yet clinically available nor is it sufficiently validated for decision making. Although TNBC behaves differently from other subtypes of breast cancer, with higher local and distant metastasis rates and earlier pattern of relapse, breast conservation and multimodality options for care in the early breast cancer setting remain similar to other subtypes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree