and Karl Reinhard Aigner3

(1)

Department of Surgery, The University of Sydney, Mosman, NSW, Australia

(2)

The Royal Prince Alfred and Sydney Hospitals, Mosman, NSW, Australia

(3)

Department of Surgical Oncology, Medias Clinic Surgical Oncology, Burghausen, Germany

In this chapter, you will learn about:

The leukaemias

The acute leukaemias

Chronic lymphocytic (lymphatic) leukaemia

Chronic myeloid (granulocytic) leukaemia

The lymphomas

Hodgkin lymphoma (previously called Hodgkin disease)

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas

Multiple myeloma

19.1 The Leukaemias

Leukaemia is a cancer of blood-forming cells. Leukaemias are classified into two broad groups according to the type of blood-forming cell that has become malignant. These are called lymphatic leukaemia and myeloid (or non-lymphatic) leukaemia.

In lymphatic leukaemia, the cells that have become malignant are the bone marrow cells that normally make lymphocytes. Lymph nodes and lymphoid tissue are usually involved and some nodes become enlarged. In myeloid leukaemia, the cells that have become malignant are cells in the bone marrow that normally make the other types of white blood cells (i.e. myeloid cells that make polymorphs and other white cell types). The spleen usually becomes involved and enlarged.

Leukaemias may be acute or chronic according to whether the disease would tend to run a rapid and rapidly fatal course (acute leukaemia) or whether the disease would progress more slowly (chronic leukaemia).

Thus there are four main types of leukaemia:

It is important to distinguish between the major types of leukaemia because they tend to run different courses and respond differently to different treatments.

Acute lymphocytic (lymphatic) leukaemia (ALL)

Acute myeloid (non-lymphatic or granulocytic) leukaemia (AML or ANLL)

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL)

Chronic myeloid (non-lymphocytic or granulocytic) leukaemia (CML or CNLL or CGL)

19.1.1 Incidence and Prevalence of Leukaemias

Leukaemias occur throughout the world but the incidence varies in different countries and in different races. All types of leukaemia are slightly more common in males. The Scandinavian countries and Israel have the highest incidence and the lowest reported incidence is in Chile and Japan, but in general they are more common in developed countries (see Appendix). In the United States, the highest incidence is in Jews and the lowest is in African Americans.

The overall incidence of ALL and AML is about equal but there is a distinct age difference. Acute leukaemia accounts for about half of all cancers in children, and acute lymphocytic leukaemia is the most common of all cancers in young children, with a peak incidence of between 2 and 4 years. The incidence of AML is low in children but increases with age.

Acute leukaemia accounts for about half of all cancers in children.

The causes of leukaemia are unknown although some predisposing factors are recognised. Leukaemias, especially myeloid leukaemias, have been linked with ionising radiation. There is also evidence that exposure of a foetus to X-rays during its mother’s pregnancy is associated with a slightly increased risk of leukaemia developing later in childhood. However, there is no evidence that normal use of diagnostic X-rays in adults is associated with leukaemia. Myelofibrosis (myelodysplastic disease) is a disorder of bone marrow cell proliferation that sometimes presents in adults as anaemia of no obvious cause and commonly degenerates into an acute leukaemia.

Excessive exposure to some chemical agents such as benzene is associated with a slightly increased risk of leukaemia. AML will occasionally develop in patients who have had some other form of cancer including Hodgkin lymphoma or cancer of the ovary that has been treated with chemotherapy.

Use of anti-cancer cytotoxic drugs for other cancers, and especially their prolonged use with radiotherapy, also slightly increases the risk of later development of leukaemia.

Familial leukaemia is rare although some families with multiple cases of leukaemia have been reported. In general, siblings of a child with leukaemia have only a slightly higher risk of developing leukaemia although if one identical twin develops acute leukaemia the other twin has about a 20 % chance of developing the disease.

People with Down’s syndrome have a 20 times greater risk of developing acute leukaemia than other people. Women who become mothers at an advanced age not only have an increased risk of producing children with Down’s syndrome but otherwise normal children born of older age group mothers have a slightly greater risk of developing acute leukaemia.

Genetic mutations and complex gene rearrangements are of basic importance in the pathogenesis of leukaemias and lymphomas. There is presently a great deal of study of these chromosome changes. Studies indicate that the chromosomal and genetic changes not only show different patterns in different forms of leukaemias but genetic patterns may also indicate likely responses to different treatments and an indication of likely progress.

There were increased numbers of people with leukaemias after the atomic bomb explosions at Hiroshima and Nagasaki and after the Chernobyl atomic energy plant disaster in Russia; CML was the most prevalent.

Viruses are known to cause leukaemia in some animal species but only one type of leukaemia in humans has been linked to a virus. Adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma, prevalent in the Caribbean, Japan and New Guinea, is probably caused by a human virus designated “T-cell leukaemia virus” (HTLV-1). The Epstein–Barr virus has been implicated in Burkitt’s lymphoma/leukaemia.

19.2 The Acute Leukaemias

19.2.1 Clinical Presentation

19.2.1.1 Acute Lymphatic (Lymphoblastic) Leukaemia (ALL)

This is the most common form of leukaemia in children with an age peak of about 5 years. Symptoms are caused by replacement of normal blood-forming cells of bone marrow by malignant leukaemic cells and infiltration (invasion) of other tissues such as the spleen, lymph nodes, tonsils and sometimes liver, kidneys, lungs and brain.

Fever, weakness, anorexia (loss of appetite), pallor and infection are common. Infection is especially common in the region of the tonsils or anus and the lungs may also become infected causing pneumonia. There may be pain in bones or joints.

The lymph nodes, tonsils and spleen are commonly enlarged. Sometimes the liver and kidneys are enlarged.

Platelets may be deficient and there may be petechial spots or bruising or signs of bleeding from any site especially from the gums, the digestive tract or anus. Bleeding in the brain or from the lungs may also occur. Thrombosis (clots) may also develop in veins.

Meningitis due to leukaemic cell spread into the meninges frequently occurs in patients with ALL unless prevented by radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

19.2.1.2 Acute Myeloid Leukaemia

AML more commonly affects adults. Anaemia, bleeding or bruising and infection are the likely presenting features. But as with ALL, general ill health with fever, lassitude, loss of appetite and involvement of other tissues or organs with septicaemic infection is likely.

19.2.2 Investigations

The diagnosis of leukaemia can be made only after careful examination of blood and bone marrow. Blood is taken by a needle from a vein in the arm and bone marrow is usually taken with a small instrument that is used to puncture a bone of the pelvis (the iliac crest). Bone puncture is painful so it is done under local or even general anaesthesia. A pathologist then examines the blood and bone marrow for leukaemic cells and for other features of leukaemia. These may include anaemia (with a reduction in numbers of red blood cells), reduction in number of normal white blood cells and reduction in the number of platelets. About one-third of patients with acute leukaemia will have an elevated white blood count, one-third will have a low white blood count and in one-third the white cell count is about normal.

Patients with AML are usually found to have abnormalities of chromosomes. There may also be changes in blood chemistry, including increased uric acid that may be associated with features of gout.

Encouraging progress has been made in recent years in the treatment of the acute leukaemias.

Cytogenetic studies on bone marrow are now part of a full investigation of leukaemia patients. These studies identify specific molecular genetic syndromes and help in selecting the best therapy. They also give a good indication of the likely prognosis.

19.2.3 Treatment

Encouraging progress has been made in recent years in the treatment of the acute leukaemias.

The best opportunity to achieve the maximum cure of leukaemia is when the disease is first diagnosed. Cells that remain after the first treatment tend to develop resistance to drugs. It is therefore important that patients with acute leukaemia should immediately be referred to a readily available specialist clinic so that the most effective treatment can be given under expert supervision without delay.

Chemotherapy using cytotoxic drugs and cortisone forms the basis of modern treatment. Combinations of effective cytotoxic drugs have produced best results.

With the best current treatment methods, more than 90 % of children and about 80 % of adults with ALL now achieve complete remission (i.e. the disease apparently disappears and the patient feels and looks well again).

Because after a time most ALL patients will develop the disease in the meninges, the lining around the brain, and because anti-cancer drugs do not pass in high concentration into the nervous system, injections of cytotoxic drugs are given into the meningeal space around the brain and the brain is also treated by radiotherapy. In the case of AML, nervous system involvement does not occur so often, but this treatment is also given immediately if there is any sign that there may be brain or central nervous system involvement.

With AML, good results of chemotherapy have not been as reliable as with ALL. Recently, in attempts to further improve results, bone marrow transplantation has been used effectively, especially in younger people (aged under 50). In marrow transplantation, the leukaemic cells are destroyed by big doses of chemotherapy and radiotherapy (total body irradiation). This is a dangerous procedure and is carried out only in highly expert units within specialised hospitals. The patient is then given an infusion of bone marrow taken from a matched donor (i.e. a donor with similar body cells unlikely to cause a rejection reaction). The best donor is often a sibling or other family member. Bone marrow transplantation involves a number of risks and should therefore be carried out only by appropriately trained experts, in specially equipped hospitals. Results have been most encouraging in this otherwise fatal illness. An alternative source of haemopoietic stem cells for transplantation is to use peripheral blood stem cells or umbilical cord stem cells. Blood stem cells are collected from the blood after stimulation by colony-stimulating factors (like G-CSF). Although controversial from an ethical and moral point of view, embryonal stem cells may have the ability to respond in the bone marrow in a similar way to bone marrow-derived cells.

In recent years, treatment with immunotherapy has been further investigated. Although major success has not as yet been achieved, there have been interesting results that give hope for better treatments in the future.

Transplantation of matched unrelated bone marrow (bone marrow from a matched donor person not related to the patient) is used to elicit graft versus leukaemia effect. The immunological effect of the graft might be as important as or even more important than chemotherapy. In recent years mini–allogeneic transplants have been used (allogeneic stem cells are used without myelo-ablative chemotherapy). Studies are proceeding to determine whether such interventions might be safer and equally effective.

During the acute illness, there may be special problems of anaemia, lowered resistance to infection, bleeding or even clotting. These may require blood transfusion or platelet transfusion and antibiotics or other treatment for infection. Aspirin should be strictly avoided because it interferes with blood clotting.

Case Report

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

Elizabeth is a 5-year-old girl whose mother took her to their family doctor with a 4-week history of increasing lethargy, loss of appetite, pallor and low-grade intermittent fevers. The doctor noted that Elizabeth was pale and had a pulse rate of 140 per minute with a systolic flow heart murmur. She had scattered petechiae (little red spots) on the lower limbs and a moderately enlarged but non-tender liver. Blood count revealed low haemoglobin (56 g/L), a raised white cell count (9 × 109/L), differential predominately blast cells and a low platelet count (15 × 109/L).

Elizabeth was admitted immediately to the children’s hospital, where compatible platelets and packed red blood cells were administered to correct the thrombocytopenia and anaemia. Under general anaesthesia, a bone marrow aspirate was performed, confirming the diagnosis of ALL. A lumbar puncture contained no white cells (suggesting that cerebral involvement was unlikely). An indwelling central venous catheter was inserted.

Elizabeth commenced chemotherapy treatment. A national childhood ALL protocol was used. This is an international programme based on a very effective German protocol in which a steroid (prednisolone) is given first. Her peripheral blast, white cell, count fell (to less than 0.1 × 109/L) after the first week of oral prednisolone. She continued induction therapy (receiving intravenous vincristine, daunorubicin and asparaginase), in addition to the oral prednisolone. A repeat bone marrow aspirate at the completion of the first 5 weeks of therapy indicated haematologic remission with no detectable blast cells (primitive white cells). Chemotherapy continued on an outpatient basis, followed by four doses of high-dose methotrexate intravenously over 8 weeks and a final extended phase (using mercaptopurine daily and methotrexate weekly) for a total of 2 years of therapy. Minimum residual disease (MRD) assays performed on marrow obtained at the completion of both the first (induction) phase and completion of the second (consolidation) phase were both negative for disease.

Comment

Elizabeth has as good an outlook as is possible to have for childhood ALL. Her gender, age at diagnosis and peripheral white cell count at diagnosis are all long-recognised indicators of a favourable prognosis. The favourable response to prednisolone as a single agent is a highly reliable indicator of responsiveness established by German studies in the late 1980s as a key determinant of required intensity of therapy. The negative MRD assays at day 33 and day 72 are, in 2005, the most advanced and sensitive indicators of an optimal response to therapy. Elizabeth has a better than 90 % chance of being cured.

19.3 Chronic Lymphocytic (Lymphatic) Leukaemia

CLL tends to occur in older people with an average age of about 60 years and is usually a very slowly progressive disease. In this disease there is an overproduction of mature and relatively normal-looking lymphocytes resulting in increased numbers of lymphocytes in the blood.

19.3.1 Clinical Presentation

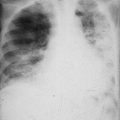

The most obvious feature is lymph node enlargement. Enlarged lymph nodes may be felt as lumps in the sides of the neck, in the axillae or groins. Enlarged lymph nodes in the abdomen are more difficult to feel but enlarged lymph nodes in the chest may be detected in a chest X-ray. The spleen and sometimes the liver may also be enlarged. The normal bone marrow may be replaced by malignant lymphocytes and the patient may become anaemic and deficient in platelets. This may lead to bleeding and clotting problems. Due to the replacement of normal white cells by abnormal white cells, the patient has decreased ability to combat infection and may also have immunologic abnormalities.

19.3.2 Investigations

Blood count, bone marrow biopsy and tests of immune function will establish the diagnosis.

19.3.3 Treatment

CLL may be present for years without causing troublesome symptoms. Many patients may not need treatment for months or years. The median age is about 60 years and there is an increased family incidence. There is no evidence that chronic lymphatic leukaemia can be cured by early treatment, so treatment is usually reserved for episodes of the disease that are causing the patient to feel ill or causing other problems. Eventually fatigue, malaise, weight loss, bleeding and symptoms of anaemia will develop. In its early stages, treatment of symptoms only may be all that is needed but eventually more aggressive treatment may be necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree