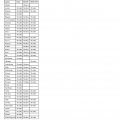

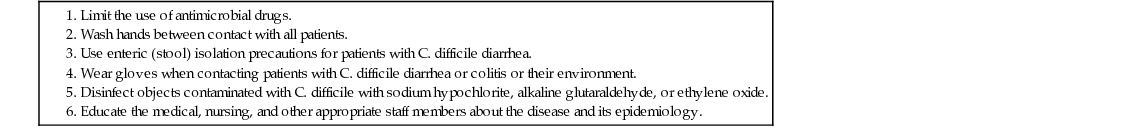

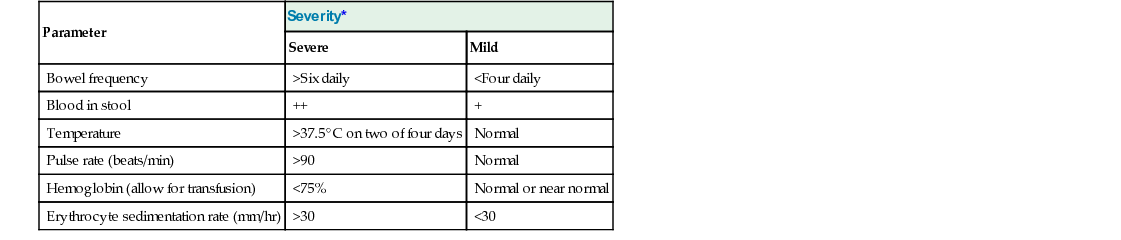

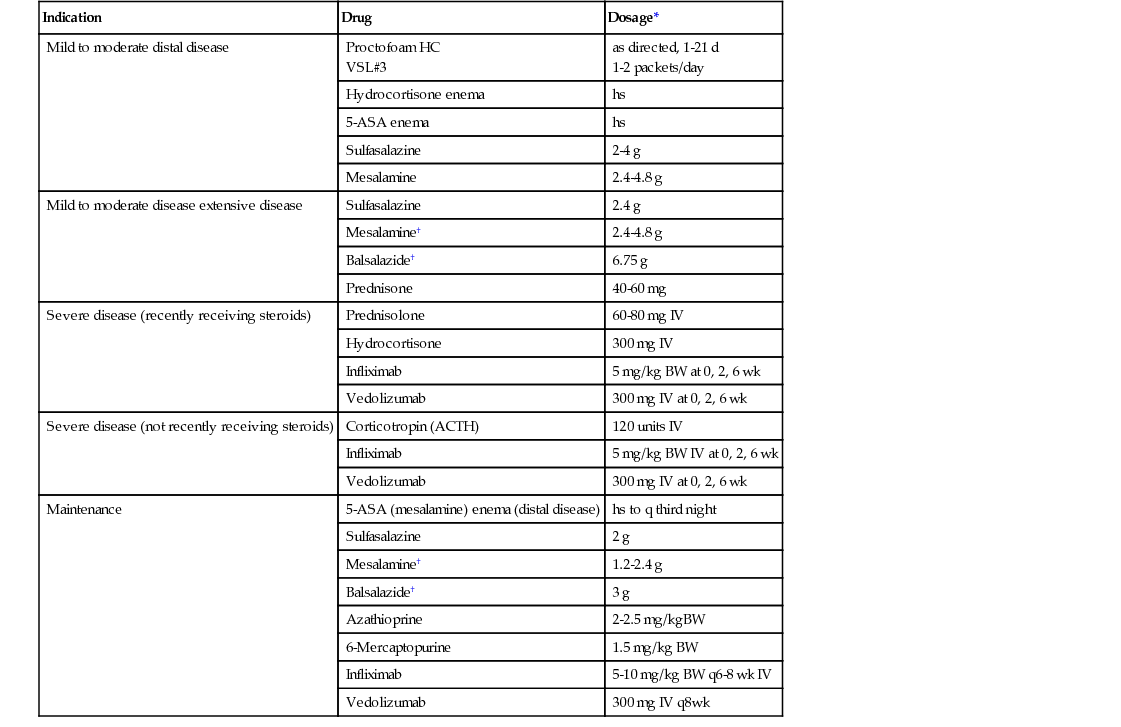

Arnold Wald The colon is a large hollow organ derived embryologically from the primitive midgut and hindgut.1 The appendix and transverse and sigmoid colons have mesenteries, whereas the ascending and descending colons do not. Like the stomach and small intestine, the colon has circular and longitudinal smooth muscle layers but, uniquely, the longitudinal muscle of the colon is separated into three bundles, known as taenia. The configuration of the taenia causes the colon to be divided into haustral folds, which presumably help slow the passage of fecal material and thus facilitate absorption. The superior mesenteric artery supplies the right colon to the midtransverse colon, whereas the inferior mesenteric artery supplies the left colon.2 The anorectum derives its blood supply from branches of the internal iliac arteries.3 In the distal transverse to mid-descending colon, the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries are linked by a series of anastomoses known as the marginal artery of Drummond. This anatomic arrangement increases the vulnerability of this area to ischemic damage. Innervation of the colon is via the autonomic nervous system and enteric neurons.4 Parasympathetic innervation is by the vagus nerve in the right colon and by sacral parasympathetics from the second, third, and fourth sacral nerves. Sympathetic innervation is derived from the lowest cervical to the third lumbar nerves via the splanchnic nerves. However, colon function may persist, even after vagal or splanchnic interruption, because of the presence of a well-developed enteric nervous system that can function in the absence of extrinsic innervation. The principal functions of the colon and rectum are to store fecal wastes for prolonged periods of time and expel them in a socially appropriate manner. Storage is facilitated by adaptive compliance of the bowel and by muscular contractions of colonic smooth muscle, which retard the forward movement of stool, thereby promoting electrolyte and water absorption and reducing stool volume. Forward movement occurs principally by relatively infrequent peristaltic contractions, which move intraluminal contents over long distances. Continence is maintained by the recognition of rectal filling and coordinated function of the anal sphincters and pelvic floor muscles to defer defecation until appropriate. Colonic motility and transit in healthy older adults are similar to those in younger individuals,5 whereas aging is associated with diminished anal sphincter tone and strength as well as a less compliant rectum.6 These latter changes may lead to greater susceptibility to fecal incontinence in older adults (see Chapter 105). Fecal incontinence can also be the presentation for other illnesses, in which impaired mobility, dehydration, dyspraxia, or other disorders are the cause. The recognition of this is part of the storied history of geriatric medicine; even so, the diagnosis and management of this socially debilitating problem is often poorest in older adults.7 The major symptoms of colonic and rectal disorders are constipation, diarrhea, pain, and rectal bleeding. The conditions that produce these symptoms are not unique to older adults; those occurring with increased frequency in older adults include diverticulosis, neoplasms, ischemic colitis, vascular ectasias, fecal incontinence, constipation, and antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis. Inflammatory bowel diseases occur in all age groups, but their onset is less likely in older adults. Contrast examination of the large intestine has traditionally been done by using barium sulfate in a single- or a double-contrast technique in which a thickened barium suspension is used to coat the mucosa, followed by insufflation to expand the viscus. Alternatively, water-soluble contrast agents can be used if perforation is suspected. The single-contrast technique is preferred when studying patients with suspected obstruction, diverticulitis, or fistula, whereas the double-contrast technique is preferred for demonstrating fine mucosal lesions and neoplasms. Although there continues to be some controversy concerning the choice of barium contrast or colonoscopy when investigating colonic diseases, most clinicians favor colonoscopy for its greater sensitivity and opportunity for biopsy and therapy. Contrast studies may be indicated for patients in whom severe stricturing disease or adhesions make colonoscopy hazardous, conditions such as diverticulitis are suspected, if the location and nature of a colonic obstruction require assessment, and if functional and structural information are required. A barium enema should not be attempted when increases in colon pressure may worsen the patient’s condition—for example, in patients with suspected toxic megacolon or those with peritoneal signs that suggest ischemic colitis. When patients complain of constipation or a recent change in bowel habit, barium radiography complements sigmoidoscopy in detecting organic causes, and they are also useful in diagnosing functional megacolon and megarectum. Complete filling of the colon with barium is neither necessary nor desirable in patients with megacolon. However, conventional barium studies provide limited information about colonic motor function in most patients with chronic constipation.8 Moreover, they are frequently inadequate in frail or hospitalized older patients.9,10 In general, fluoroscopy of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract has moved from being a first-line study for evaluating GI symptoms to its role as a problem-solving tool. This procedure allows visualization of the thickness of the bowel wall, solid viscera within the abdomen, mesenteries, and soft tissues adjacent to the bowel. It offers a modest advance in the diagnosis of diverticulitis by demonstrating inflammation of pericolic fat, abscesses that may contain collections of fluid and gas, and intramural sinus tracts. Fistulas to other organs can be identified when gas is found in the bladder or vagina. It also can identify extension of disease at a distance from the colon, including unsuspected intraabdominal abscesses. Computed tomography (CT) is also valuable when evaluating and managing complications of Crohn disease, including abscesses, fistulas, involvement of psoas muscles and ureters, and occasionally for percutaneous drainage of collections. Other complications, including sacral osteomyelitis, cholelithiasis, nephrolithiasis, and vascular necrosis of the femoral head associated with corticosteroid therapy, can also be diagnosed. In appendicitis (and cecal diverticulitis, which is usually misdiagnosed as appendicitis), CT may augment the clinical diagnosis by showing the periappendicular inflammatory process and differentiating phlegmon from abscess.11 Occasionally, appendicoliths are identified, which are considered pathognomonic of appendicitis when associated with periappendicular inflammatory signs. CT colonography is a technique devised to detect colon polyps for screening purposes. Detection rates for colonic polyps larger than 6 mm are similar to colonoscopy, but the test has low sensitivity for smaller polyps.12 The use of three-dimensional evaluation in addition to two-dimensional evaluation may reduce perceptual errors.13 CT colonography is recommended as an alternative for colon polyp screening in the United States. Although CT remains the most widely used imaging modality for patients with nonbiliary symptoms and nonspecific and acute abdominal pain, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has had an increasing role in the evaluation of bowel disease.14 Its advantages over CT include the absence of ionizing radiation and superior tissue contrast, but it does involve longer acquisition times, increased susceptibility to motion artifact, and higher cost. MR enterography and colonography are the preferred techniques for evaluating small bowel and colonic involvement by inflammatory bowel diseases. MRI may be comparable to endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) in staging rectal cancer but, unlike EUS, it can evaluate stenosing and high rectal tumors while simultaneously imaging the entire pelvis to evaluate for adjacent organ invasion and lymphadenopathy. MRI is also a valuable tool to evaluate anorectal disease, particularly so for perianal fistulas, which may be a complication of Crohn disease, to optimize surgical planning.15 This procedure accurately delineates the layers of the rectal wall, internal and external anal sphincters, and levator muscles.16 Endosonography is useful in evaluating pelvic floor structures in many patients with fecal incontinence to detect occult sphincter injuries arising from childbirth or other conditions associated with potential injury to continence mechanisms.17 EUS is a rapid, minimally invasive technique used to image rectal polyps and detect focal malignancy within polyps, tumor masses penetrating into the bowel wall, and extramural lesions, such as prostatic tumors and ovarian lesions. Perirectal fistulas and abscesses can also be evaluated, including determination of whether there is destruction of pelvic muscles. It is considered the reference standard for the preoperative staging of rectal and anal cancers, with relatively high accuracy in categorizing tumors and lymph nodes.18 These procedures are usually performed in the prepared colon, except when evaluating diarrheal illnesses. Colonoscopic examinations provide unparalleled evaluation of the mucosal surfaces and opportunities for biopsy and therapy. These include diagnosis and determining the extent of inflammatory bowel disease, evaluation of patients with overt or occult GI bleeding, evaluation of chronic watery diarrhea, endoscopic sampling and removal of polyps, decompression of sigmoid volvulus or functional megacolon, and ablation of vascular lesions. Colonoscopy is generally done under conscious sedation, whereas flexible sigmoidoscopy often is not. In many older patients, the physician must be aware of their increased sensitivity to sedatives and analgesic medications. Because older adults are susceptible to hypotension and respiratory depression, careful monitoring of the patient during the procedure is especially important. Even in older patients, such procedures are generally safe in experienced hands and when done in units that monitor blood gases and cardiorespiratory functions. Major complications include bleeding and perforation, which should not occur more than once in 1000 routine procedures. Mucosal biopsies are indicated when evaluating undiagnosed diarrhea, in long-standing ulcerative colitis during surveillance for precancerous dysplasia, when obtaining tissue for viral culture, and in evaluating polypoid or ulcerated lesions. In patients with inflammatory disorders of the colon and rectum, biopsies serve to establish the presence, extent, and distribution of colitis to differentiate ulcerative colitis from Crohn colitis and these disorders from other inflammatory conditions, such as infectious colitis. Biopsies should be obtained from endoscopically normal as well as abnormal areas, because characteristic changes may be patchy and therefore could be missed if too few biopsies are obtained. This is especially true in pseudomembranous, collagenous, and lymphocytic colitides, in which the distal colon may be spared. Because hypertonic phosphate enemas and purgative laxatives may induce mucosal changes that can be mistaken for mild colitis, they should be avoided when evaluating suspected inflammation of the colon. Fecal occult blood tests (FOBTs) identify hemoglobin or altered hemoglobin compounds in the stool. Foods containing peroxidases, such as melon and uncooked broccoli, horseradish, cauliflower, and turnips, may produce false-positive results, whereas reducing agents such as ascorbic acid may decrease sensitivity.19 Tests that extract the protoporphyrin from hemoglobin, such as HemoQuant, are more specific and quantitative but are also more time-consuming and expensive. Rehydration of Hemoccult slides increases sensitivity but decreases specificity and is not recommended. A weakly positive slide may become negative after 2 to 4 days of storage. Oral iron supplements do not interfere with any of these tests. The guaiac FOBT is being replaced in many population screening programs for colon cancer and polyps by the fecal immunochemical test (FIT), which detects the intact globin protein portion of human hemoglobin. A labeled antibody attaches to the antigens of any human hemoglobin present in stool, resulting in a positive test. Studies have shown that FIT offers superior sensitivity for advanced colorectal neoplasms (e.g., cancer, advanced adenomas) over that provided by the standard guaiac test.20 As a result, stool guaiac tests are no longer recommended by any of the U.S. guidelines for colorectal cancer screening. Colonic diverticula are herniations of colonic mucosa through the smooth muscle layers. Diverticula occur in areas of anatomic weakness of the circular smooth muscle created by penetration of blood vessels to the submucosa. They are usually found in the sigmoid and descending colons and rarely, if ever, in the rectum.21 This disorder has been recognized with increasing frequency in modern Western countries.22 Colonic diverticula are present in about one third of persons by the age of 50 years and in about two thirds by the age of 80 years. Dietary fiber insufficiency and the increased longevity of modern Western populations have long been hypothesized to explain the increased prevalence of diverticulosis. Dietary factors may promote increased colonic motor activity and intraluminal pressures, whereas aging may lead to structural weakness of the colonic muscle.21 However, recent studies have challenged the concept that low-fiber diets and constipation contribute to the development of diverticulosis.23 Other studies have suggested that genetic factors may play a role.24 Because diverticula are asymptomatic in most individuals, caution should be taken before attributing nonspecific GI symptoms to them.25 Painful diverticular disease is characterized by crampy discomfort in the left lower abdomen. Symptoms are often associated with constipation or diarrhea, as well as with tenderness over the affected areas. These symptoms are similar to those of irritable bowel syndrome and of partial bowel obstruction due to tumors or ischemia. Studies have shown that these patients have altered motor activity in the segments containing diverticula, which are associated with reporting of abdominal pain.26 In contrast to diverticulitis, there is no fever, leukocytosis, or rebound tenderness. Diverticulitis develops in approximately 10% to 25% of individuals with diverticulosis who are followed for 10 years or more; however, fewer than 20% of these patients require hospitalization. Recent studies have found that among patients with diverticulosis, higher levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D—25(OH) vitamin D—are associated with a lower risk of diverticulitis.27 This suggests that screening for (and correcting) low 25(OH) vitamin D levels may reduce the risk for diverticulitis, although this is an unproven hypothesis. Inflammation begins at the apex of the diverticulum when the opening of a diverticulum becomes obstructed (e.g., with stool), leading to micro- or macroperforation of a diverticulum.28 The presence of a palpable mass, fever, leukocytosis, and/or rebound tenderness indicates an inflammatory process, which often remains localized in the adjacent pericolic tissues but may progress to a peridiverticular abscess.29 Other complications include fibrosis and bowel obstruction, fistula formation to the bladder, vagina, or adjacent small intestine, and free perforation with peritonitis. The frequency of complications rises significantly with recurrent attacks of diverticulitis. Making a clinical distinction between painful diverticular disease and diverticulitis carries a sizable rate of error.28 In an older or debilitated patient, the absence of fever, leukocytosis or rebound tenderness does not exclude diverticulitis.29 A disorder characterized by localized inflammation associated with diverticulosis (SCAD [segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis] syndrome) has been described in older symptomatic patients.30 Symptoms appear after the age of 40 years and are usually characterized by rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Other disorders such as carcinoma, inflammatory bowel disease, and ischemia may mimic symptomatic diverticular disease. Diagnostic studies include barium enema, CT, MRI, ultrasonography, and colonoscopy. In most cases of suspected diverticulitis, barium enema should be delayed for about 1 week to allow some resolution of the inflammatory process. A single-contrast study should be performed cautiously to minimize the risk of perforation. Radiographic findings suggesting diverticulitis include longitudinal fistulas connecting diverticula over segments of colon, fistula into adjacent organs, a fixed eccentric defect in the colon wall, contrast outside the lumen of the colon or diverticulum, and intraluminal defects representing abscesses.21 CT, MRI, and ultrasonic imaging of the abdomen provide superior definition of colonic wall thickness and extraluminal structures and are the procedures of choice at the time of initial evaluation. Colonoscopy is a less attractive option during an acute episode and is best used to exclude tumors or other conditions if other diagnostic tests are inconclusive. The treatment of painful diverticular disease is designed to reduce symptoms based on smooth muscle spasm in contrast to the treatment of diverticulitis, which is designed to treat bacterial infection (Table 78-1). Patients with severe pain, nausea, and vomiting or complications should be hospitalized and given intravenous antibiotics until clinical improvement occurs. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons has recommended an individualized approach to elective surgery for diverticulitis and laparoscopic management, when possible.31 TABLE 78-1 Medical Treatment of Diverticular Disease Propantheline bromide (15 mg tid); dicyclomine hydrochloride (20 mg tid); hyoscyamine sulfate (0.125-0.250 mg q4h) Oral* Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate (875/125 mg bid) or Ciprofloxacin (500 mg bid) plus metronidazole (500 mg tid) Parenteral Gentamicin or tobramycin (5 mg/kg/day) plus clindamycin (1.2-2.4 g/day) or Levofloxacin 500 mg daily plus metronidazole (500 mg q8h) or Piperacillin-tazobactam (3.375-4.5 g q6h) Surgery is recommended for patients with diverticulitis who fail to respond to medical therapy within 72 hours, immunocompromised patients, and those who have fistula to the bladder with pneumaturia and urinary infection or fistula to the vagina with discharge of stool into the vagina. A one-stage operation, in which the diseased segment of bowel is resected and continuity restored by a primary anastomosis, is preferred.32 In cases of generalized peritonitis or emergent surgery for perforation with abscess or high-grade obstruction, a two-stage procedure requiring a diverting colostomy should be used.33 Large abscesses can often be drained percutaneously by an interventional radiologist using CT or ultrasonography as a guide.34 Elective surgery can then be performed after 2 to 3 weeks of antibiotic therapy, often allowing for a single-stage resection. Emergent surgery is required for generalized peritonitis or persistent high-grade bowel obstruction. Most patients with complicated diverticular disease require surgery, even if clinical recovery occurs, because there is a high risk of recurrent attacks. In addition to changes in surgical management, recent studies have suggested that a person with uncomplicated acute diverticulitis can be safely managed as an outpatient, and the long-standing recommendation that antibiotics are needed in all patients has been challenged.24 A survey of Dutch surgeons and gastroenterologists has found that 90% of them manage mild diverticulitis without antibiotics,35 which is in accordance with recently published Danish national guidelines.36 Most patients with SCAD respond to 5-aminosalicylate therapy, with long-term resolution of the disease. On occasion, spontaneous remissions may occur, or persistent, chronically active disease may require resective surgery.30 Bleeding associated with diverticula is typically brisk and painless and often arises from the proximal colon. Bleeding is thought to occur when a fecalith erodes into a vessel in the neck of the diverticulum or there is rupture of the penetrating arteriole in its course around the diverticular sac.21 An important indication for emergent colonoscopy is to identify the source of bleeding in patients with diverticula, because other lesions not seen by contrast studies may be the actual source. If bleeding is brisk, a bleeding scan or selective mesenteric angiography can locate the site of bleeding; superselective embolization of distal arterial branches has been demonstrated to be highly effective and relatively safe (<25% ischemia rates37; see section “Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding”). Older patients with appendicitis are at increased risk (≈60%) for perforation. They have a higher mortality rate and often do not exhibit a fever or an elevated white blood cell count.38 The onset of abdominal pain is abrupt, begins in the midabdomen, relocates to the right lower quadrant, and is often associated with nausea, vomiting, and fever. Physical examination characteristically reveals signs of local peritonitis in the right lower quadrant, and the white blood cell count is frequently elevated. The differential diagnosis includes pyelonephritis, Crohn disease, gastroenteritis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian cyst, and cecal diverticulitis. In older patients, appendicitis may occur in association with colon cancer in which low-grade obstruction results in distention of the appendix and mimics true appendicitis. If the diagnosis is uncertain, ultrasonography has been shown to have positive and negative predictive values of about 90% for appendicitis and is also useful in identifying another cause of symptoms in patients with right lower quadrant pain.39 One sonographic criterion for acute appendicitis is visualization of a noncompressible appendix with a diameter more than 6 mm. First described as a cause of diarrhea in 1978, Clostridium difficile is responsible for approximately 3 million cases of diarrhea and colitis each year and is the most common cause of hospital-acquired diarrhea in the United States.40 The vast majority of cases are associated with two protein exotoxins, A and B, produced by C. difficile. Toxin A is an enterotoxin that triggers diarrhea, epithelial necrosis, and a characteristic inflammatory process in animals, whereas toxin B is a cytotoxin in tissue culture but does not by itself cause toxicity in animals.41 The disease spectrum ranges from mild diarrhea, with little or no inflammation, to severe colitis often associated with pseudomembranes, which are adherent to necrotic colonic epithelium. Acquisition of C. difficile occurs most frequently in older adults in hospitals or nursing homes, potentially because of environmental contamination with C. difficile and spores carried on the hands of the hospital or institutional staff.42 Acquisition is often asymptomatic but may have clinical consequences if older patients receive certain antibiotics or chemotherapeutic agents. Other possible risk factors include surgery, intensive care, nasogastric intubation, and length of hospital stay. A smaller number of patients have antibiotic-associated diarrhea but no evidence of C. difficile infection. Although virtually all antibiotics have been implicated, the most common are cephalosporins, ampicillin, amoxicillin, and clindamycin.43 Less commonly implicated antibiotics are macrolides, sulfonamides, and tetracyclines.40 One of the most important developments has been the emergence of a new epidemic strain that is resistant to quinolones such as ciprofloxacin.44 This strain produces high levels of toxins A and B and also more spores, which can increase risk for contamination; it has spread quickly throughout the United States.40 Increasingly, quinolones have been commonly associated with C. difficile infection (CDI), especially with the epidemic BI strain. The typical clinical picture of C. difficile–associated colitis includes nonbloody diarrhea, lower abdominal cramps, fever, and leukocytosis. Fever is usually low grade although, on occasion, it can be quite high. In severe cases, dehydration, hypotension, hypoproteinemia, toxic megacolon, or even colonic perforation may occur. In severely ill patients, the diagnostic test of choice is flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy. Because the distal colon is involved in most cases, flexible sigmoidoscopy is usually satisfactory; however, changes may be confined to the right colon in up to one third of cases, making colonoscopy necessary if less extensive procedures do not confirm a suspected diagnosis. The yellowish-gray pseudomembranes are densely adherent to the underlying colonic mucosa, interspersed with mucosa that appears normal. Mucosal biopsies may exhibit characteristic findings of epithelial necrosis and micropseudomembranes (so-called volcano lesions), even when pseudomembranes are not grossly visible. Endoscopy should be performed in severely ill patients who present atypically and therefore require a rapid diagnosis.45 The enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for toxin A and/or B has been the primary test used in most clinical laboratories, but it is too insensitive and nonspecific to be used as a stand-alone test. In contrast, the use of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay to detect the gene for toxin production (ted B gene) has been increasingly regarded as a superior test that is rapid and sensitive, with a minimum detection limit of 105 bacteria per gram of stool. Although more expensive, it is far more sensitive than EIA. One drawback is that the test will lead to an overdiagnosis of CDI because it does not detect the toxin.46 This may lead to a two-step algorithmic approach, as has been adopted by the National Health Service laboratories in England as of April 2012.40 The offending drug should be discontinued if possible. If symptoms persist, patients who are not seriously ill should receive oral metronidazole, 250 mg tid or qid, for 10 to 14 days. Patients who are seriously ill and those with complicated or fulminant infections should receive oral vancomycin, 125 mg PO qid, for 10 days.47 If oral intake is not possible, metronidazole, 500 mg IV q6h, is given until oral administration can be accomplished. In patients with ileus, vancomycin enemas can be administered. Metronidazole and vancomycin appear to be therapeutically comparable in non–seriously ill patients, but metronidazole costs less, and there are current concerns about vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE).48 In general, fever resolves within 24 hours, and diarrhea decreases within 4-5 days. Fidaxomicin is a macrocyclic antimicrobial agent that has little or no systemic absorption after oral administration and which, in in vitro studies, is more active than vancomycin against CDI. It appears to be more effective than vancomycin in patients who require ongoing concomitant systemic antibiotics and also may be associated with a lower incidence of recurrent CDIs.45 Relapses average about 20% to 25% following successful treatment with either agent,49 often involving sporulation, which leads to relapse within 4 weeks after completion of successful treatment. These episodes invariably respond to another course of antibiotic therapy. About 5% to 10% of patients have multiple relapses. In such individuals, vancomycin in conventional doses should be followed by a 3-week course of cholestyramine, 4 g tid and/or Lactinex (a probiotic supplement), 500 mg PO qid, or vancomycin, 125 mg PO every other day. Some have advocated a 6-week schedule consisting of a 2-week course of vancomycin given daily in the standard dose, a 2-week course of the same dose given every other day, followed by a 2-week course at the same dose given every third day. In addition, some have advocated the use of Saccharomyces boulardii, a nonpathogenic yeast that inhibits the binding of toxin A to rat ileum, with consequent prevention of enterotoxicity.50 Because the pathogenesis of recurrent CDI involves an ongoing disruption of the normal fecal flora and an inadequate host immune response, fecal microbial transplantation (FMT) has become an increasingly popular approach to patients with multiple recurrent infections. This involves infusion of a liquid suspension of intestinal microorganisms from the stool of a healthy donor via intestinal intubation, colonoscopy, or enema. The existing literature indicates that FMT is effective and safe, with no serious adverse effects reported to date, and a response rate of 90% or higher.51 Guidelines for prevention of C. difficile diarrhea and colitis are based on a few simple practices. See Table 78-2.52 TABLE 78-2 Practice Guidelines for Prevention of Clostridium difficile Diarrhea These organisms consist of four groups: A (Shigella dysenteriae), B (Shigella flexneri), C (Shigella boydii), and D (Shigella sonnei). Group D accounts for most clinical infections in Western countries. In contrast to other enteric pathogens, very few organisms are needed to produce infection, which is spread by fecal-oral transmission between humans and that continues to occur, despite high standards of water purification and sewage disposal. At least 30 gene products are involved in Shigella invasion and its intercellular spread. Disease is caused by the invasion of colonic epithelial cells, perhaps in part mediated by cytotoxins produced by S. dysenteriae and S. flexneri, but enterotoxins may also contribute to early symptoms of nondysenteric diarrhea.53 Enterotoxins similar to Shiga-like toxins secreted by enterohemorrhagic E. coli are believed to mediate the hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) associated with severe colitis caused by S. dysenteriae type I. Colitis is heralded by the passage of bloody mucoid stools associated with urgency, tenesmus, abdominal cramping, fever, and malaise. The frequency of stools is highest during the first 24 hours of illness and gradually diminishes thereafter. Stool examination reveals numerous polymorphonuclear cells, and leukocytosis is common. Stool culture grown on selective media is the definitive diagnostic study. Sigmoidoscopy is usually not necessary but, if done, will demonstrate a friable hyperemic mucosa. Barium contrast studies are not indicated. If the illness is mild and self-limited, antibiotics can be withheld. Because resistance to sulfonamides, ampicillin, tetracycline, and even trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is now common, treatment with a fluoroquinolone (e.g., ciprofloxacin 500 mg bid for 5 days) is indicated for older or debilitated patients with acute disease to shorten the illness and the duration of fecal excretion of the organism.54 Antidiarrheal agents prolong the clinical illness and carrying of the organism and should not be administered.55 The development of a chronic carrier state is rare and difficult to treat. These organisms commonly cause disease in developed countries and are a major cause of diarrhea in tourists visiting underdeveloped countries. Because older adults have been increasingly engaging in overseas travel, these organisms can be a major impediment to a successful trip. Of the five major classes of pathogenic E. coli, only enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) and Shiga toxin–producing E. coli (STEC) primarily involve the colon. Both produce a clinical illness similar to that of shigellosis. Once thought to be a pathogen restricted to developing countries, STEC has been shown to produce diarrhea in the United States and is a relatively uncommon cause of traveler’s diarrhea. It is more difficult to identify in stool cultures and is not a reportable illness. The clinical illness is generally milder than with shigellosis. A reasonable approach is to treat with a fluoroquinolone, similar to treatment for shigellosis.53 Preventive measures include eating cooked food only while it is still hot and avoiding local water, including fruits and vegetables washed with local water. In older tourists, the disease can be shortened by prompt use of a fluoroquinolone.53 This organism has been identified as a major pathogen in the United States and Canada, causing approximately 70,000 U.S. cases annually.53 In addition to sporadic infections, epidemics have been traced to the consumption of undercooked and raw ground beef, because healthy cattle serve as the primary reservoir for STEC strains. Infections have also been associated with exposure to patients with bloody diarrhea, contaminated water supplies, and nonpreserved apple cider. Clinical manifestations include nonbloody diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis, and HUS.56 Unlike most bacterial enteric diseases, E. coli O157:H7 is often characterized by low-grade fever or the absence of a fever.57 The pathogenesis of colitis has been linked to Shiga-like toxins (verocytotoxins 1 and 2), which bind to a glycolipid on the surface of colonocytes, but adherence factors may also play a role. Older age is a risk factor for this infection and increases the risk of HUS and death. It is generally believed that antibiotics are not indicated for active infections and appear to predispose to HUS.56 An important emerging group of related pathogens are the non-O157 (STEC), which can produce an illness similar to O157:H7 strains.58 In Europe, most STEC strains belong to the non-O157 serogroup. Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli are among the most common bacterial causes of diarrhea and can be manifested by gastroenteritis, pseudoappendicitis, and/or colitis. These organisms are usually transmitted from animals to humans through contaminated food and water and sometimes by direct contact with pets. Constitutional symptoms usually precede diarrhea and abdominal cramps by up to 24 hours, and colitis may be characterized by fever and dysentery lasting for 1 week or more. Diagnosis is made by stool culture. Convalescent carriage up 5 weeks (mean) is common after the onset of illness and is significantly reduced by antimicrobial treatment. Although the infection is usually self-limited, antibiotics may be given if the illness is severe or if the patient is immunosuppressed.59 Treatment consists of erythromycin or fluoroquinolones; macrolides such as azithromycin and clarithromycin show excellent in vitro activity. Resistance rates to fluoroquinolones of up to 88% have been reported in Europe and Asia. In areas of high resistance, azithromycin, 500 mg daily for 3 days, is an effective alternative. This organism remains a primary cause of dysentery, which may be complicated by fulminant colitis, toxic megacolon, bleeding, stricture, and perforation. Severe disease is more common in older adults and in patients who are immunosuppressed or debilitated.60 The disease is typically acquired by ingesting cysts from contaminated water or fresh vegetables but can also be transmitted through sexual practices that promote fecal-oral transmission. Studies on germ-free animals have suggested that intestinal disease does not develop unless bacteria are present. This may partly account for the effectiveness of metronidazole, which is also active against anaerobic bacteria. The traditional method of diagnosing intestinal E. histolytica is by the microscopic inspection of three separate stool specimens. A wet preparation should be obtained within 30 minutes of passage to look for motile trophozoites, which may contain ingested red blood cells. A formalin–ethyl acetate concentration preparation should be examined for cysts. Barium, bismuth, kaolin compounds, magnesium hydroxide, castor oil, and hypertonic enemas all interfere with the ability to detect the parasite in stools.60 This technique is only 50% to 60% sensitive and can give false-positive results. Antigen detection methods have numerous advantages to microscopy techniques, including higher sensitivity and specificity and good correlation with molecular techniques.61 Colonoscopy may reveal erythema, edema, friability of the mucosa, and scattered ulcers 5 to 15 mm in diameter, covered with a yellow exudate. These ulcers may occur anywhere in the colon but are most common in the cecum and ascending colon. Biopsies from the edge of these ulcers may reveal typical hourglass ulcers containing trophozoites. Cathartics and enemas should not be used because they interfere with identification of the parasite. Because these techniques may miss identifying the parasite, serologic tests for antiamoebic antibody should also be obtained in suspected cases. The indirect hemagglutination assay (IHA) is positive in 75% to 90% of patients with amoebic dysentery and in virtually all patients with amoebic liver abscesses. The IHA remains positive for years after treatment of invasive amoebiasis.60 An alternative test is the use of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect serum IgA antibodies to the organism.61 Treatment of acute amoebic dysentery consists of metronidazole, 750 mg tid, for 5 to 10 days or, if not tolerated orally, 500 mg q6h by the intravenous route.62 This should be followed by phenobarbital (Luminal amebocytes)-acting oral drugs such as paromomycin, 25 to 35 mg/kg tid, for 7 days, or iodoquinol, 650 mg tid daily, for 20 days, to eliminate all cysts and prevent possible relapse. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a member of the beta herpesvirus group, which transitions to a lifelong latent phase after primary infection in immunocompetent individuals. In patients who are immunocompromised, with diminished T cell function, reactivation may occur and may become persistent, with the reappearance of immunoglobulin M (IgM) anti-CMV antibodies in the serum. Among the GI syndromes associated with CMV are focal and diffuse colitis. CMV colitis is associated with severe small-volume diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever. Colonoscopy may reveal variable degrees of focal erythema, petechial hemorrhage, erosions, and, in advanced cases, scattered ulcers. Mucosal biopsy may reveal characteristic intranuclear inclusions (owl’s eye lesions) or cytoplasmic inclusions in vascular endothelial cells. In cases in which biopsy is not diagnostic, the PCR assay or in situ hybridization techniques may be helpful, together with serum IgM CMV-specific antibodies. The treatment of choice is ganciclovir (5 mg/kg IV, q12h, for 21 days) to achieve remission.63 For patients who relapse after discontinuation of the drug, chronic maintenance therapy (6 mg/kg five times/week) may be instituted. Valganciclovir is as effective as IV ganciclovir because of improved bioavailability over previous oral agents. Because the drug has hematologic side effects such as neutropenia, regular blood counts should be carried out. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients with CMV colitis should be placed on maintenance therapy indefinitely. Foscarnet (60 mg/kg q8h, adjusted for renal function) is used for patients who do not respond to ganciclovir or who cannot tolerate its toxicity. Both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are more common in early adulthood but are found with increased frequency in older adults. In part, this is because increasing numbers of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) now live into old age. In addition, ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease exhibit a bimodal age of onset,64,65 with the peak incidence occurring in the third decade and a minor later peak between the ages of 50 and 80 years. Over 10% of cases have their onset after the age of 60 years. This pattern persists even when other diseases that mimic inflammatory bowel disease, such as ischemic colitis and infectious causes, have been excluded. The reasons for this bimodal pattern are unknown. Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory process of unknown cause that affects the mucosa and submucosa of the colon in a continuous distribution. Enhanced humoral immunity is more evident in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn disease and probably reflects disturbed immunoregulation, leading to unrestrained T cell activation and cytokine release.66 Histologically, there are diffuse ulcerations and epithelial necrosis, depletion of mucin from goblet cells, and polymorphonuclear and lymphocytic infiltration involving the superficial layers of the colon to the muscularis mucosa. The finding of crypt microabscesses is characteristic but not pathognomonic. The inflammatory process invariably involves the rectum and extends proximally for variable distances but does not involve the GI tract proximal to the colon. Involvement of the rectum only is designated ulcerative proctitis, whereas disease extending no further than the splenic flexure is known as left-sided disease. Symptoms in older patients are similar to those seen in younger persons.67 The severity of ulcerative colitis may be classified as mild, moderate, and severe and is generally proportional to the extent of colonic inflammation (Table 78-3). Most patients exhibit diarrhea, with or without blood in the stools, although older patients with proctitis only occasionally present with constipation or hematochezia. Systemic manifestations occur during more severe attacks and carry a poorer prognosis. Despite the occurrence of less extensive disease in older patients, older adults more often present with a severe initial attack and have higher mortality and morbidity rates than younger patients.68 TABLE 78-3 Proposed Criteria for Assessment of Disease Activity in Ulcerative Colitis Toxic megacolon is a feared complication of ulcerative colitis, which occurs more frequently in older patients. Abdominal radiographs show colonic dilation, often to impressive proportions, and patients may exhibit mental confusion, high fever, abdominal distention, and overall deterioration.69 Extraintestinal manifestations may occur in ulcerative colitis, including arthralgias, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, uveitis, and migratory polyarthritis. These disorders occur less frequently than in Crohn disease and are generally associated with increased disease activity. The diagnosis is made by sigmoidoscopy and rectal mucosal biopsies because the disorder invariably involves the rectum. The extent of the disease is determined by colonoscopy or barium radiography, both of which should be avoided in patients who are severely ill because of the danger of inducing perforation or toxic megacolon. The characteristic findings are diffuse erythema, granularity, and friability of the mucosa, without intervening areas of normal mucosa. Inflammatory pseudopolyps indicate more severe erosion of the mucosa and must be distinguished from true polyps. Particularly in older adults, it is important to exclude other diseases that may mimic ulcerative colitis, including Crohn colitis (see later), ischemic colitis, radiation proctocolitis, and diverticulitis. In acute presentations, infectious agents should be excluded with appropriate stool cultures, including Salmonella, Campylobacter, Shigella, and Yersinia spp., amebiasis, and E. coli O157:H7. Finally, C. difficile–associated diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis should be considered in older adults, particularly those who have recently been treated with antibiotics, reside in institutions, or have recently been hospitalized. The treatment of ulcerative colitis is based on the extent and the severity of the disease (Table 78-4). Effective medical therapy consists of a number of drugs, which are administered intravenously, orally, or rectally. The major classes of drugs are corticosteroids, 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA) agents, immunomodulators, anti–tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) agents, and anti-integrin drugs.70 In older adults, some drugs must be used more carefully than in younger patients. For example, corticosteroids have a higher risk of complications, such as hypertension, hypokalemia, and confusion, whereas sulfasalazine, 5-ASA products, and immunomodulators are generally well tolerated.68 TABLE 78-4 Medical Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis Proctofoam HC VSL#3 as directed, 1-21 d 1-2 packets/day

The Large Bowel

Anatomy

Functions and Symptoms of Disorders

Diagnostic Testing

Radiologic Contrast Studies

Imaging Techniques

Abdominal Computed Tomography

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Anal and Rectal Endosonography

Colonoscopy and Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

Histopathology

Fecal Occult Blood Testing

Colonic Diverticulosis

Painful Diverticular Disease

Diverticulitis

Measure

Painful Diverticulosis

Diverticulitis

Diet

Increased fiber

Reduced fiber (or NPO)

Bulk laxative

Sometimes effective

Not indicated

Analgesic

Avoidance of narcotics

Avoidance of morphine; meperidine best

Antispasmodic

Not indicated

Antibiotic

Not indicated

Bleeding

Appendicitis

Infectious Diseases

Clostridium difficile

Shigella Organisms

Symptoms

Diagnosis

Treatment

Pathogenic Escherichia coli

Shiga Toxin–Producing Escherichia coli O157:H7

Campylobacter Species

Entamoeba histolytica

Cytomegalovirus

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Ulcerative Colitis

Histopathology

Symptoms and Signs

Parameter

Severity*

Severe

Mild

Bowel frequency

>Six daily

<Four daily

Blood in stool

++

+

Temperature

>37.5° C on two of four days

Normal

Pulse rate (beats/min)

>90

Normal

Hemoglobin (allow for transfusion)

<75%

Normal or near normal

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/hr)

>30

<30

Diagnosis

Treatment

Indication

Drug

Dosage*

Mild to moderate distal disease

Hydrocortisone enema

hs

5-ASA enema

hs

Sulfasalazine

2-4 g

Mesalamine

2.4-4.8 g

Mild to moderate disease extensive disease

Sulfasalazine

2.4 g

Mesalamine†

2.4-4.8 g

Balsalazide†

6.75 g

Prednisone

40-60 mg

Severe disease (recently receiving steroids)

Prednisolone

60-80 mg IV

Hydrocortisone

300 mg IV

Infliximab

5 mg/kg BW at 0, 2, 6 wk

Vedolizumab

300 mg IV at 0, 2, 6 wk

Severe disease (not recently receiving steroids)

Corticotropin (ACTH)

120 units IV

Infliximab

5 mg/kg BW IV at 0, 2, 6 wk

Vedolizumab

300 mg IV at 0, 2, 6 wk

Maintenance

5-ASA (mesalamine) enema (distal disease)

hs to q third night

Sulfasalazine

2 g

Mesalamine†

1.2-2.4 g

Balsalazide†

3 g

Azathioprine

2-2.5 mg/kgBW

6-Mercaptopurine

1.5 mg/kg BW

Infliximab

5-10 mg/kg BW q6-8 wk IV

Vedolizumab

300 mg IV q8wk

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The Large Bowel

78