Exenatide clinical efficacy

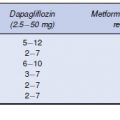

The Phase 3 clinical efficacy studies that have been conducted with exenatide are listed in Table 4.1. Three 30-week, placebo-controlled studies evaluated exenatide (5 µj.g or 10 µj.g twice daily) as add-on therapy in overweight or obese patients not achieving adequate glycaemic control despite treatment with maximally effective doses of metformin (Defronzo et al., 2005), a sulphonylurea (Buse et al., 2004), or the combination of metformin and a sulphonylurea (Kendall et al., 2005). After completion of the placebo-controlled phase, these studies continued into three long-term uncontrolled extension studies designed to demonstrate the durability of exenatide treatment (Blonde et al., 2006; Buse et al., 2007; Ratner et al., 2006). In a placebo-controlled study of 16 weeks duration, exenatide was added to existing thiazolidinedione treatment, with or without metformin (Zinman et al., 2007). In addition, three Phase 3, long-term active-comparator controlled studies have been conducted to establish the non-inferiority of exenatide treatment (10 µg twice daily) to insulin treatment (insulin glargine, once daily or biphasic insulin aspart, twice daily) in patients with inadequate blood glucose control using oral agents (Barnett et al., 2007; Heine et al., 2005; Nauck et al., 2006).

Table 4.1 Exenatide Phase 3 clinical efficacy studies

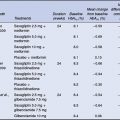

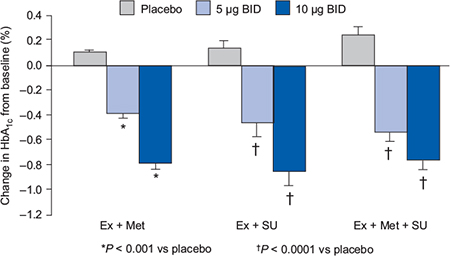

In the placebo-controlled trials, exenatide 10 µg was associated with reductions in HbA1c of 0.8–0.9% (Figure 4.2) demonstrating similar efficacy to currently available oral antidiabetes agents. All exenatide doses were associated with significant and sustained reductions in postprandial plasma glucose compared with placebo, and at the exenatide 10 µg dose, placebo-subtracted reductions in fasting plasma glucose were in the range of 1.0–1.4 mmol/L (Buse et al., 2004; DeFronzo et al., 2005; Kendall et al., 2005). All the studies have also demonstrated improvements in surrogate measures of beta-cell function such as the proinsulin:insulin ratio and HOMA-B.

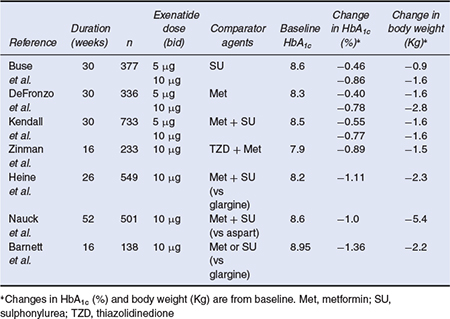

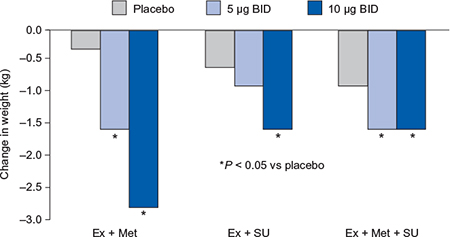

An important advantage of exenatide is that it is associated with weight loss and mean reductions of 1.5–2.8 kg were reported in the placebo-controlled trials (Figure 4.3). There was little or no increase in hypoglycaemia except as add-on to a sulphonylurea, and the antihyperglycaemic efficacy was sustained in open-label extension studies up to two years (Blonde et al., 2006; Buse et al., 2007; Ratner et al., 2006). In addition, an improvement in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides and blood pressure was observed (Klonoff et al., 2008). In the active-comparator studies, exenatide was able to achieve similar reductions in HbA1c to basal long-acting insulin and to biphasic insulin regimens and was associated with significant reductions in body weight. In the insulin glargine comparator trials, exenatide was associated with greater reductions in postprandial plasma glucose excursions, whereas insulin glargine was associated with greater reductions in levels of fasting plasma glucose (Barnett et al., 2007; Heine et al., 2005).

Figure 4.2 Exenatide effects on glycaemic control in combination with oral antidiabetes agents (Buse et al., 2004; DeFronzo et al., 2005; Kendall et al., 2005).

A long-acting release formulation of exenatide is also in development, which encapsulates exenatide in polymer microspheres that gradually disintegrate in the body to release exenatide. This formulation is suitable for once-weekly subcutaneous injection and results in significantly greater improvements in glycaemic control than exenatide given twice a day, with no increased risk of hypoglycaemia and with similar reductions in body weight (Drucker et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2007). Exenatide once weekly is also associated with less nausea, probably because of more stable circulating levels of exenatide. However, due to a larger 23 gauge needle (compared with 31 gauge needle for injection of immediate release exenatide) injection site bruising can occur more frequently. An open-label, randomized trial comparing once-weekly exenatide with insulin glargine in people with type 2 diabetes has been completed. The results suggest that weekly exenatide may be a suitable alternative to insulin in patients inadequately controlled on existing treatment, particularly where weight loss is desirable (Diamant et al., 2010). In a further Phase 3 study, once-weekly exenatide also provided greater HbA1c reductions compared with maximum dose oral sitagliptin or pioglitazone in patients inadequately controlled on metformin monotherapy (Bergenstal et al., 2010). However, in both trials more patients discontinued exenatide than the comparator therapy due to adverse effects.

Figure 4.3 Exenatide reductions in body weight in combination with oral antidiabetes agents (Buse et al., 2004; DeFronzo et al., 2005; Kendall et al., 2005).

Exenatide safety and tolerability

Nausea is the most common tolerability issue associated with exenatide, reported by at least one third of patients, and is thought to be associated with the delayed gastric emptying. It is usually mild and can be minimized by starting with the 5 µg dose for the first month before titrating up to the 10 µg dose (Fineman et al., 2004). As both exenatide and sulphonylureas stimulate the beta cells to produce more insulin, hypoglycaemia can be a problem when these agents are used in combination. Slow titration can help to reduce hypoglycaemic episodes, and the risk can also be reduced by lowering the dose of the sulphonylurea. There have been rare reports of acute pancreatitis during use of exenatide (MHRA, 2008) and as is true with all new drugs, careful attention to clinical effects that emerge over time will be necessary to ensure the drug’s safety.

Exenatide advantages and disadvantages

The major disadvantage of exenatide is that it is injected twice daily and must be administered 30 to 60 minutes before the first and last meals of the day. Exenatide raises insulin levels rapidly (within 10 minutes of administration) with levels subsiding substantially over the next 2 hours. As a dose taken after meals has a much smaller effect on blood sugar than one taken beforehand, exenatide should not be used after eating a meal. Delayed gastric emptying with exenatide may also result in a reduction in the rate and extent of absorption of orally administered drugs. Mild to moderate nausea is common with the initiation of exenatide therapy, but tends to diminish with continued exposure. Besides this, exenatide does have a number of advantages that make it more convenient than insulin. First, the volumes administered are small and injection site pain is uncommon. Second, there is no need for bottles and syringes; exenatide is supplied as a pre-filled pen device. Third, unlike insulin there is no need for dose adjustments in response to the size of meals or activity.

The major advantage of exenatide is that it is the first glucose-lowering agent to demonstrate substantial and sustained weight loss. Compared with the sulphonylureas and insulin, exenatide is not associated with hypoglycaemia as an adverse effect. Based on data from animal studies there is also a possibility that exenatide therapy may be able to preserve or even restore beta-cell function.

Exenatide current indications

Exenatide is indicated for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in combination with metformin and/or sulphonylureas in patients who have not achieved adequate glycaemic control on maximally tolerated doses of these oral therapies (Byetta SmPC, 2009). In the most recent guidance from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), exenatide is an alternative to insulin or other third-line therapy in obese patients (body mass index (BMI) of at least 35 kg/m2) who have failed to achieve adequate glycaemic control on maximal dose oral antidiabetes agents (NICE, 2009). It may also be considered in a patient with a BMI less than 35 kg/m2 if weight loss would benefit other comorbidities, or insulin therapy is not appropriate or acceptable (NICE, 2009).

Liraglutide

Liraglutide mechanism of action

Liraglutide is an analogue of human GLP-1 created by substituting one amino acid and adding a fatty acid side chain (Figure 4.1). The resultant molecule has 97% sequence identity with human GLP-1. The fatty acid side chain increases non-covalent binding to albumin after injection, which protects liraglutide from degradation by DPP-4 as well as reducing clearance. The structural modifications also allow liraglutide to self-associate into heptamers, which results in slow absorption from the subcutaneous injection site. These three characteristics combine to give the compound a plasma half-life of 10–12 hours in humans, compared with approximately 2 minutes for native GLP-1 and 2.4 hours for exenatide. The prolonged action makes liraglutide suitable for once-daily dosing. Liraglutide retains affinity for the GLP-1 receptor and produces the effects expected of a GLP-1 agonist in patients with type 2 diabetes including improved glycaemic control, increased meal-related and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, suppression of glucagon, weight loss, delayed gastric emptying and appetite suppression, and enhanced beta-cell function (for a review, see Rossi and Nicolucci, 2009). Due to the high degree of homology between liraglutide and native GLP-1, the risk of antibody formation is lower than with exenatide (Marre et al., 2009; Russell-Jones et al., 2009); however, the clinical relevance of antibodies to either agent is not yet known.

Liraglutide clinical efficacy

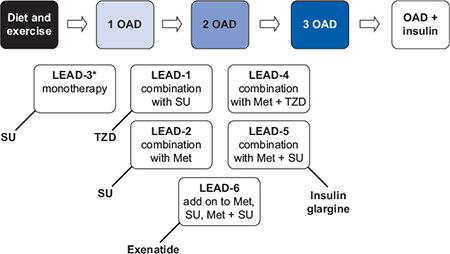

The clinical efficacy of liraglutide has been evaluated in the Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes (LEAD) programme. This was designed to assess the efficacy and safety of liraglutide across the continuum of type 2 diabetes care, both as monotherapy (off license) and in combination with commonly used oral antidiabetes agents, in a series of five randomized, double-blind, controlled trials and one open-label trial in more than 6800 people, 4600 of whom received liraglutide treatment (Figure 4.4). A unique feature of the LEAD programme was that as well as a placebo arm, all of the studies except one had active comparators.

Figure 4.4 Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes (LEAD) Phase 3 programme. Met, metformin. OAD, oral antidiabetes agent. SU, sulphonylurea. TZD, thiazolidinedione.

*Liraglutide is not licensed for use as monotherapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree