Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge research funding from the US National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Drug Abuse Grant DA037820. I thank Dr. Sarah Mars for extensive feedback and Dr. Jay Unick for creating Fig. 1.1 .

Introduction

The opioid overdose epidemic is the latest phase of a multidecade exponential increase in drug-related mortality in the United States [ ]. The severity of the current crisis has driven up the overall US mortality rate 3 years in a row from 2014 to 2017 [ ]. Correspondingly, life expectancy at birth has declined; the first triple-year decline since World War I and the devastating influenza pandemic 100 years ago [ ]. Most of the top 10 causes of death are declining year over year; however, the third leading cause of death, unintentional injuries, has climbed in rate and rank since 2014 [ ]. Driving this increase are deaths due to drug poisoning, which exceeded 70,000 in 2017 [ ]. Annual deaths due to drug overdoses now exceed those caused by motor vehicle accidents, gun violence, and even HIV infection at the height of the 1990s HIV epidemic [ ].

The focus of this chapter is on the epidemiology of the US opioid overdose epidemic. National trends and demographics will be presented first. Then, using the framework of the “triple wave,” each phase of the opioid crisis will be discussed separately in terms of regional distribution, demographics, and supply and demand drivers. It is critical to discuss the drivers of each wave to best inform policy and intervention responses.

National trends and demographics

The annual number of drug overdose deaths (all classes) grew from 16,849 in 1999 to 70,237 in 2017; corresponding to an increase in rate from 6.1 per 100,000 population in 1999 to 21.7 in 2016 [ ]. This rate more than tripled overall with an accelerated increase from 2014 to 2016 of 18% per year.

The class of drugs leading the escalation in drug poisoning, as well as the overall US mortality, is the opioids. In 2017, two-thirds of drug overdose deaths involved opioids (47,600) [ ]. There were 8050 opioid overdose deaths in 1999, with a rate of 2.9 per 100,000; this rate increased fivefold to 14.9 in 2017 [ ]. Since 1999, over 400,000 deaths have been attributed to the opioid crisis thus far.

Since 1999, overdose death rates for men were approximately twice that of women, with the rate for men tripling from 8.2 in 1999 to 29.1 in 2017. Rates increased fastest for age groups 25–34 years and 45–54 years, both achieving rates of 38 per 100,000 in 2017 [ ].

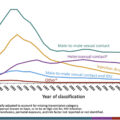

The triple-wave epidemic: opioid pills, heroin, and synthetic opioids

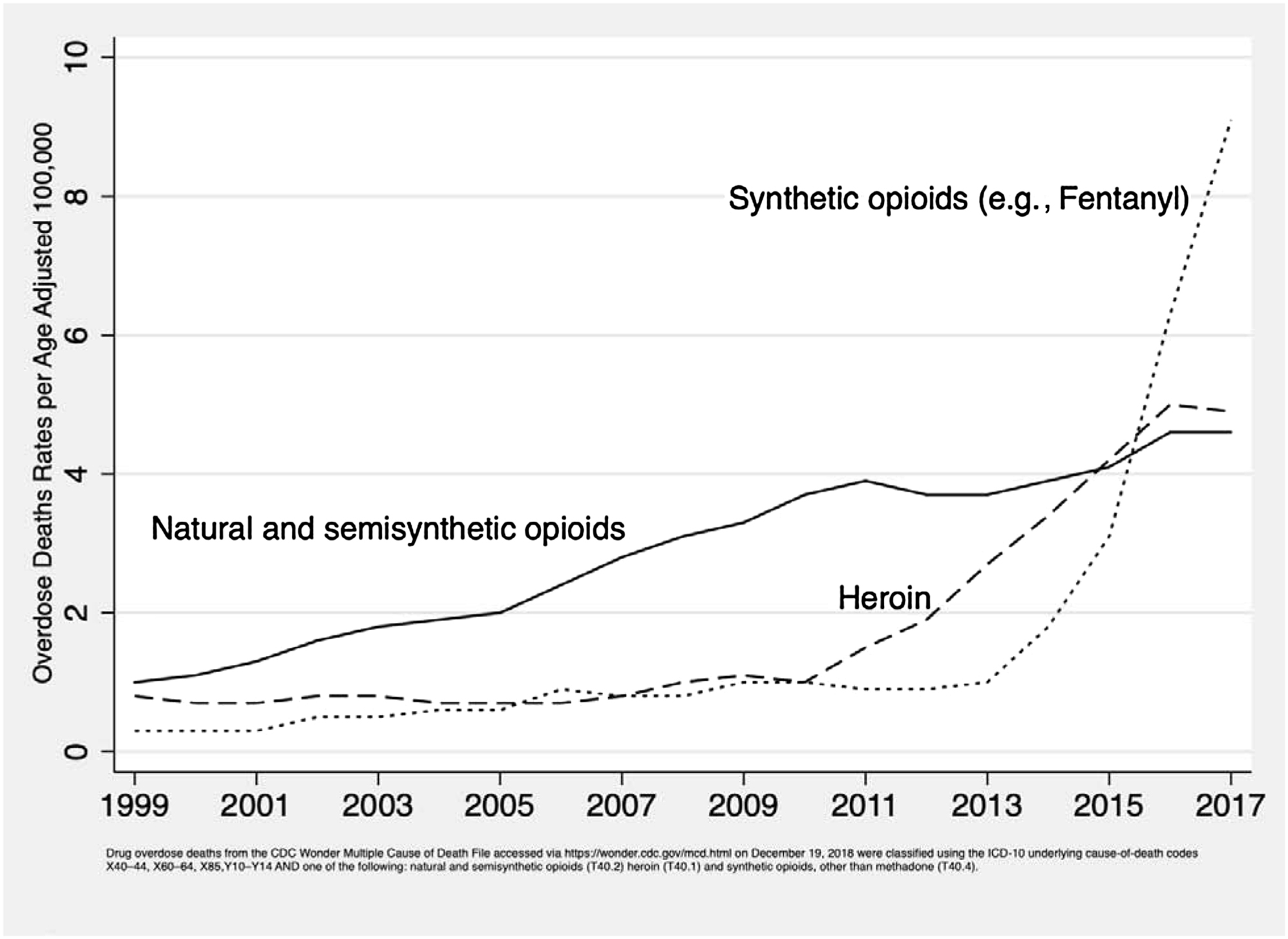

The triple wave epidemic of overdose deaths stems from three classes of opioids: prescription opioid pills (“semisynthetic opioids” in Fig. 1.1 ), heroin, and synthetic opioids other than methadone [ ]. Fig. 1.1 shows three waves of opioid mortality, each wave cresting on top of the one before it. In the first wave, overdoses related to opioid pills started rising in the year 2000 and have steadily grown through 2016. The second wave saw overdose deaths due to heroin, which started increasing clearly in 2007, surpassing the number of deaths due to opioid pills in 2015. The third wave mortality has arisen from fentanyl, fentanyl analogues, and other synthetic opioids of illicit supply; it has climbed slowly at first but dramatically after 2013. Data from 2017 show synthetic opioid deaths continuing to rise, reaching a peak of over 28,000, whereas opioid pill and heroin overdose deaths leveled off, albeit at very high levels of approximately 15,000 deaths in each category [ ].

Wave 1: prescription opioid pills

The rate of prescription opioid overdose mortality increased fourfold from 1.0/100,000 in 1999 to 4.4 in 2016 and 2017 [ ]. Men have a 50% higher rate (6.1) than women (4.2). The highest rate is among those aged 45–54 years (10.0) [ ]. Rates are higher in whites (6.9) than in African Americans (3.5) or Hispanics (2.2). By level of urbanization (e.g., metro, fringe metro, nonmetro), rates are equivalent.

The supply-side drivers underlying the first wave of prescription opioid overdose have been extensively discussed [ , ]. Wave 1 is widely considered to have been driven iatrogenically with a tripling of opioid prescriptions starting in the 1990s and peaking around 2011 [ ]. Increases in prescribing have been attributed to the changing medical culture and assertive marketing by pharmaceutical companies [ ]. The upsurge in prescriptions has been correlated to the rising adverse consequences, particularly opioid overdose [ ]. The introduction of extended-release long-acting (ERLA) opioid formulations supports both supply-side and demand-side pressure. ERLA formulations are a source of opioids in a novel form with a technologic advance that allowed higher, longer lasting doses in a single capsule. However, the ease with which their delayed-release mechanisms could be bypassed and the whole dose discharged at once, for instance, by crushing and insufflating (nasal snorting) or injecting, led to a wave of misuse [ , ].

A demand-side argument has been introduced examining the structural factors that might be driving the epidemic [ ]. The “diseases of despair” analyses highlight the extraordinary rise in death rates, among middle-aged whites without a college degree, in three related categories: drug poisoning, alcohol-related disease, and suicide [ ]. The most compelling structural determinants include an aging population with rises in reported pain and disability, economic distress, declining social cohesion, and rising psychologic malaise that may have led an at-risk population to seek opioids in the first place [ ]. In this line of reasoning, increased opioid prescribing is a “vector” of the opioid overdose epidemic, with more proximal root causes being worsening structural forces accompanied by generational hopelessness and despair [ ].

Wave 2: heroin

Heroin-related overdose mortality rates were stable from 1999 to 2007. Starting in 2008, heroin overdose rates increased fivefold from 1.0 per 100,000 (3041 deaths) to 4.9 in 2017 (15,482 deaths) [ ].

Coincident with rising heroin-related deaths, the number of heroin users [ ], especially young heroin users, has been increasing since the mid-2000s [ ]. The first two overdose waves, from opioid pills and heroin, have been termed “ intertwined epidemics” [ ]. Young and new heroin users have described the reason for transitioning from opioid pills to heroin as their growing dependence that required larger and more consistent pill supplies than they could obtain either by prescription or on the street. The more ready availability of high-purity, low-cost heroin made the switch to heroin economically logical and difficult to resist [ ].

Drug treatment data show that in successive cohorts from the 1960s through the 2000s, patients admitted to treatment with heroin use disorder increasingly reported starting their opioid use disorder with opioid pills [ ]. However, this has begun to change as an increasing proportion of patients with heroin use disorder entering treatment report heroin as their first experience of an opioid [ ]. Overdoses due to heroin began to accelerate in 2011. In late 2010, OxyContin, a brand-name ERLA formulation of oxycodone, was reformulated to be abuse-deterrent. The reformulation of this popular diverted opioid pill may have had the unintended consequence of driving a small proportion of the at-risk population to heroin use [ ]. In sum, we have seen elements of demand-side drive in wave 2, with rising numbers of heroin users transitioning from opioid pill dependency followed more recently by younger persons initiating first with heroin.

Although “intertwined,” the first and second opioid overdose waves show some contrasts in age and regional distribution. Examining the years 2012–14, the age distribution of patients hospitalized for opioid pill overdose had its largest peaks in the 50- to 64-year-old group. Meanwhile, the peak age group for heroin overdose admissions was 20- to 34-year-old people. In this data, we see possible evidence of population-level transitions from opioid pills to heroin use as the rates for overdose among 20- to 34-year-old people declined for opioid pills but, in the same period, increased for heroin [ ]. Heroin overdose mortality is three times higher among men (7.3/100,000) than women (2.5). Although whites have higher rates (6.1) than African Americans (4.9), rates are increasing in the recent years among the latter [ ].

Geographic disparities are also evident—in contrast to the national spread of opioid pill overdose, heroin-related overdose is much higher in the US Northeast and Midwest regions, along with higher rates of increase [ ]. Some of this regional disparity may be endemic, stemming from the 1970s, but there are also significant new supply-side forces shaping it. A dramatic transformation in the US heroin supply, including changes in its country of origin, has occurred in the past 10 years. Prior to 2000, heroin was imported from four source regions/countries in the world, including Southeast Asia, Southwest Asia, Mexico, and South America (Colombia). The 2000s began an era in which most US heroin was transshipped by transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) from two countries: Colombia and Mexico [ ]. Regional heroin distribution became starkly divided with Colombia sourced heroin predominant in the eastern United States while “black tar” heroin from Mexico being the major source-form in the western United States [ , ]. Accelerating this trend from oligopoly to monopoly, Mexican TCOs have increasingly dominated the US heroin market, with their market share increasing from 50% in 2005 to 90% in 2016 [ ].

Mexico-sourced heroin is also becoming more refined. From 2005 to 2012, a growing and substantial proportion of the analyzed heroin samples obtained in the eastern US cities by the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) for its Heroin Domestic Monitor Program were from an unknown source and of unknown quality. Subsequent DEA analyses have led to the conclusion that a more refined heroin has emerged from Mexican sources. This so-called “Mexican White” is a mimic of high-quality Colombia-sourced powder heroin, replacing it in its traditional retail outlets of the Northeast and Midwest [ ].

Wave 3: synthetic opioids

Synthetic opioids in the heroin supply, chiefly illicitly produced fentanyl, are responsible for the third wave of overdose mortality [ , ]. Mortality due to fentanyls, including chemical analogues, has increased dramatically, with a doubling in number and rate between 2013 and 2016 (2016: 5800 deaths; 5.9/100,000) [ ]. By 2016, fentanyl overdose rates are almost three times higher in men (8.6) than those in women (3.1). The age group with the highest numbers of deaths (5976) and rate (13.4/100,000) is 25- to 34-year-old people. Whites have higher rates of fentanyl mortality (7.74) than African Americans (5.55); however, the recent rate of increase is much higher in the latter, i.e., 140.6% average annual increase in 2011–16. Regional disparities are also evident, with the Northeast, Midwest, and mid-Atlantic regions most impacted.

”Heroin,” particularly in the Northeast and Midwest, the regions with the greatest increases in wave 2 overdose, currently exists as fentanyl-adulterated and/or fentanyl-substituted heroin (FASH) [ ]. Illicitly manufactured fentanyl is integrated into the illicit drug supply and sold as “heroin” in powder form, or as counterfeit opioid or benzodiazepine pills [ ].

Fentanyl is the main chemical in a growing family of chemical analogues. These analogues come in a range of morphine-equivalent potencies, with some such as butyryl-fentanyl being less potent than fentanyl by weight while others have much greater potency [ ]. In addition, there are other novel synthetic opioids in circulation, including U47700 and U48800. The greatest concern arises from a branch of the fentanyl family that includes some exceedingly potent opioids such as carfentanil, sufentanil, and remifentanil. It is unclear whether these extremely potent fentanyls will become established elements in the opioid marketplace or if they are just accidents or experiments in the rapidly evolving illicit opioid supply.

According to the US DEA, the current main source of illicitly manufactured fentanyls is China. Fentanyls sourced from China take a number of routes on their way into the United States, including internet purchases, routing through Canada (typically pill form), or through Mexico in powder or pill form [ ]. Perhaps the most revealing aspect of the supply that fuels the US fentanyl epidemic is its regional discreetness. Comparing drug seizure data with overdose death data, one finds a remarkable geographic correlation between fentanyl seizures and synthetic opioid overdoses [ ]. These fentanyl events overlap in the same regions as wave 2 heroin overdose: the Northeast, mid-Atlantic, and Midwest. The reasons for this regional disparity are unclear. One possibility is that fentanyl distribution is regionally orchestrated by a branch of the Sinaloa TCO [ ]. Another hypothesis is that source forms of powder heroin, predominant in the Northeast and Midwest, are more easily adulterated with powder fentanyls than solid “black tar” heroin, which predominates in the western United States [ , ]. Such stark regional disparities support the notion that the third wave is a supply-side event [ ]. A demand-driven or culturally driven event, such as through entrepreneurial or individual internet purchases, would more likely have led to a more even geographic spread of fentanyl-related overdose or one that reflected similar social conditions in separate geographic locations.

The “Iron Law of Prohibition” suggests that highly potent-by-volume drugs such as fentanyl are expected due to the honing effects of interdiction [ ]. Following this is the concern that constraining the mother chemical, fentanyl, too robustly and too rapidly will foster the supply of fentanyl analogues. The number of known fentanyl analogues exceeds 200; the number of potential fentanyl analogues could exceed several hundred more. Care must be taken not to foster the ingenuity and creativity of illicit drug manufacturers to push in even more dangerous directions. Based on this concern, the DEA has imposed a first-ever class restriction on the family of fentanyls, the utility of which is uncertain.

Ethnographic research with persons who use heroin confirms that the introduction of FASH has been unexpected and unsettling, that fentanyl was not a demand-driven phenomenon, and that there is a range of desirability for FASH from abhorrence and avoidance through acceptance to enthusiasm [ , ]. Those who favor fentanyl are nevertheless hampered from choosing it in the marketplace by its concealed identity as “heroin” or counterfeit brand-name pills [ , , ]. Importantly, cultural idioms for fentanyl have been slow to emerge despite 4 years of steady supply; slang terms have arisen for most desired illicit drugs and their absence, in this case, is evidence for a lack of strong demand. Consequentially, emergence of slang can be seen as a marker for the growing acceptance of fentanyl.

In addition to the dangerous potency of fentanyl, ethnographic observations support the notion of a possibly greater danger: rapid changes in potency and purity, as well as varying mixtures of heroin, fentanyl, and its analogues [ , , ]. Australian research on heroin overdose has shown that fluctuations within a wider range of street heroin purity, particularly when around a higher mean purity level, are an independent predictor of a fatal overdose [ ]. Vicissitudes in the potency/purity/mixture of FASH in the street market may be discovered to have profound effects on the overdose rate in a given location.

Conclusion

The triple-wave opioid overdose epidemic is an intertwined, three drug subclass epidemic. All three waves have impressive supply-side drivers including excessive prescribing of medication, a new form of highly refined Mexico-sourced heroin, and a new illicit source of synthetic opioids adulterating heroin and counterfeit pills. Demand for opioid pills partially drove demand for heroin while demand for heroin unsuspectingly feeds demand for synthetics-as-substitute. Increases in opioid mortality are now driven by deaths due to FASH. The second and third waves are regional, with the Northeast (including mid-Atlantic) and Midwest (including Appalachia) being the most affected regions.

Positive supply shocks are historically correlated with upswings in drug use and consequences and the same can be seen in the current opioid crisis. Fentanyl, in particular, comes as a positive supply shock leading to disastrous consequences. It is thus tempting to focus efforts on controlling supply. There is evidence that supply-side interventions can work if part of a comprehensive program also includes demand reduction [ ]. Unipolar supply-side interventions, however, may cause paradoxical unwanted results (for example, see Ciccarone et al. 2009 [ ]). These phenomena may be occurring within the current crisis. Downward pressure on opioid prescribing may be driving a portion of the at-risk population from opioid pill misuse to heroin, thus exposing them to the even more dangerous family of fentanyls. Another driver of unintended consequences may have been the reformulation of ERLA opioids to abuse-deterrent formulations, examples of which include OxyContin and Opana, with misuse of the latter implicated in the Scott County Indiana HIV outbreak [ ]. The goals of curtailing excessive prescribing practices or creating abuse-deterrent formulations may be reasonable, but the untoward consequences must be recognized, monitored, and responded to accordingly.

Considering the inadequate and paradoxical effects of current opioid supply interventions, supply-side policies must be combined with sufficient investments in and expansion of effective prevention, substance use treatment, and harm reduction services [ ]. Opioid use disorder has a number of medical treatment options that have been shown to be medically efficacious as well as cost-effective [ ]. Improving access to medical treatment for opioid use disorder is vital; for this, efforts must be placed on workforce expansion, improving medical education, expanding insurance coverage, and reducing regulatory barriers [ , ]. In particular, reducing the regulatory burdens on prescribing buprenorphine and providing performance-based metrics and incentives for its use should greatly enhance access to this evidence-based treatment [ , ]. The US Surgeon General has called for greater distribution of naloxone, the opioid antagonist used to treat an opioid pill, heroin, or fentanyl overdose [ ]. Achieving a wider distribution of naloxone into the community is an essential strategy in the current epidemic [ , ]. Sterile syringe provision must be greatly expanded to meet the increasing population at risk. Drug surveillance and drug checking can be utilized as a harm reduction strategy [ , ]. Supervised consumption spaces can aid in the prevention of overdose and can reduce HIV and HCV transmission risks [ ]. These services can act as a safety net or hub for persons at risk and provide them with necessary resources and referrals to services [ ].

References

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree