Introduction

The conundrum of diabetic painful and painless neuropathies was clinically described centuries ago , more lately in 1983 on the natural history of acute painful neuropathy , and then again in 1992 as follows: “Diabetic neuropathies form a group of diverse conditions: it is notable that there are very marked distinctions between those which recover (acute painful neuropathies, radiculopathies, mononeuropathies) and those which progress (sensory and autonomic neuropathy). There are many clinical, structural and physiological differences between these groups” . Furthermore, one brilliant case study in 1999 reported that peripheral painful neuropathy could be a third neuron disease . Over time many dedicated clinicians have secured a detailed description of the natural history and signs and symptoms of painful and painless peripheral neuropathy on which today’s researchers base their efforts.

Distal symmetrical sensory neuropathy is easily the most common pattern of neuropathy in people with diabetes with a lifetime prevalence of around 50% and it is associated with diabetic painful neuropathy in up to 40% of all cases . Presence of diabetic painful neuropathy without simultaneous peripheral sensory neuropathy is practically nonexisting or very rare—and preexisting sensory neuropathy, therefore, seems to be a prerequisite for the development of painful neuropathy . It is unknown whether the two conditions purely coexist, or a more distinct causative association exists .

Overall, the pathophysiology and natural history of diabetic painful and painless neuropathy remain an enigma to many clinicians, researchers, and persons with diabetes.

Clinical presentations and highly variable patterns of neuropathy

Sensory loss may go completely undetected in diabetes, as there are literally no symptoms, whereas neuropathic pain often forces the person with diabetes to contact the general practitioner or hospital healthcare-professional for relief of symptoms. It may present as sharp, shooting, deep pains of a burning, itching, or deep musculoskeletal qualities, at times of unbearable intensity, but fortunately it is more often represented by mere uncomfortable symptoms of pins and needles and a tingling sensation, and at times numbness that interferes with daily activities and quality of life. The onset may be insidious symptoms gradually changing and increasing in intensity—and symptoms tend to decrease after lengthy periods, often years, where after the person with diabetes is left with the peripheral sensory loss. The paradox of coexisting anesthesia of the feet and at the same time excruciating pains is intriguing as well as simultaneous numbness and hypersensitivity (personal clinical observations). Adding to these observations, it has been shown that a smaller number of persons with painful diabetic neuropathy report “gain of function” signs such as allodynia and hyperalgesia . In spite of these clear variabilities in the individual clinical presentations, neurological examinations tend to be nearly identical in persons with painful and painless neuropathy . At a more personal level, the person suffering moderate to severe neuropathic pain may experience a degree of physical disability, depression, anxiety, insomnia, and a poorer quality of life than patients with painless neuropathy . It remains unclear whether the overall severity of neuropathy is greater when painful neuropathy is present. Some studies have shown an association linking severity of impairment of neuropathy with presence and intensity of painful neuropathy and others have shown the opposite . Along the same lines, a detailed cross-sectional study confirmed that painful neuropathy is associated with severity of sensory neuropathy and thermal hyposensitivity , and a second detailed cross-sectional study has demonstrated that a hyposensitivity sensory phenotype together with an increased severity of neuropathy both are associated with painful diabetic neuropathy . Collectively, the evidence suggests that an increased severity of diabetic peripheral neuropathy may be linked to a risk of developing painful neuropathy, although painful neuropathy also sometimes exists in people with mild or moderate diabetic peripheral neuropathy. However, the evidence also points toward that severe diabetic peripheral neuropathy and painful neuropathy are not mutually exclusive .

Risk factors for developing diabetic peripheral and neuropathic pain

Risk factors for developing a medical condition or complication are something that is frequently debated and researched in the field of medicine, but while we are very aware of the risk factors for developing, that is, a diabetic foot ulcer or painless diabetic peripheral neuropathy, the evidence of risk factors for developing or progressing to painful diabetic neuropathy remains sparse. Age, alcohol, body mass index, ethnicity, sex, diabetes duration, diabetes type, glycemic control, microangiopathic complications, waist circumference, hypertension, and smoking all emerge as risk factors for developing diabetic peripheral neuropathy in general, but very little data are currently available regarding painful neuropathy. The longitudinal National Health Service Survey in the United States from 1989 reported an association between self-declared hyperglycemic events, glycosuria, and painful symptoms , but successive epidemiological studies have failed to clearly establish the association, although most of these only consider current glycemic status and do not asses these longitudinally. Some studies have indicated that diabetes duration, age, or sex might be predictors for the development of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy only for other studies to find opposite results, although there appears to be an overweight of studies indicating female gender as an individual risk factor. Also, retinopathy, nephropathy, and peripheral arterial disease have been associated with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in one or several studies, but again other studies have failed to present similar findings. Of all the risk factors tested in the literature, obesity and waist circumference seem to be the most promising risk factors for developing painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy at least in people with type 2 diabetes. In particular, a cross-sectional study, characterized by a multilevel approach to diagnosing painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy and simultaneous careful exclusion of other painful neuropathies, confirmed that body mass index was an independent predictor of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in a multiple logistic regression analysis .

Despite the promising findings regarding obesity, the overall evidence regarding any independent risk factors for developing painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy remains extremely limited and cannot provide sufficient information for neither clinicians nor researchers to predict the onset of neuropathic pain . Therefore, like it is the case with most comparisons between painful and painless diabetic peripheral neuropathy, it is not exactly clear why some people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy have neuropathic pain, while others have not. Simultaneously, like it is the case with the development of diabetic foot ulcers, not all people with diabetes will develop diabetic peripheral neuropathy despite having all the affirmed risk factors, which presents researchers and clinicians with another issue in predicting which people to intervene on in both primary prevention studies and in a clinical setting. This limitation hampers the much-needed research in primary prevention, as thousands of participants would be needed in order to achieve any meaningful power and thereby to detect and evaluate preventive measures.

Huge unmet clinical needs and treatment challenges

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy, painful and painless, contributes to an array of downstream consequences affecting persons with diabetes physically, mentally, and with regard to quality of life and the impact of living with chronic or longstanding pain . Loss of sensation in the feet causes balance problems increasing the risk of falls reinforced by diminished vision due to retinopathy, vestibular dysfunction, and motorneuropathy . A dominant complication to peripheral neuropathy is the risk of foot ulceration and lower extremity amputations as more than 15% of all persons with diabetes in their lifetime will experience a foot ulcer and more than 80,000 amputations are performed yearly . The financial costs to healthcare due to diabetic neuropathy are estimated to be as high as 13.7 billion US dollars in the United States alone and the majority attributed to type 2 diabetes and foot complications . Societal burdens and healthcare expenses are bound to increase at high rates if early diagnosis and treatment interventions are not optimized. As of now there exists no efficient, disease-modifying treatment and diagnosis often takes place when clinical challenges are prominent. But above all, the person with diabetes suffering complications to peripheral neuropathy is paying heavily due to foot ulcerations, amputations, falls, pain, life expectancy, and quality of life.

Current status for detecting painful and painless neuropathy

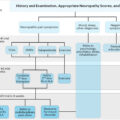

Detection and monitoring of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in clinical practice are recommended in most clinical guidelines including consensus statements from the Toronto Diabetic Neuropathy Expert Group and the American Diabetes Association . Despite the frequent occurrence, screening for diabetic peripheral neuropathy is at times neglected leading to a considerable diagnostic delay and insufficient preventative measures. The reasons are many, but most important are the lack of quick and reliable screening methods for painful and painless neuropathy . Current clinical practice is, therefore, often limited to screening for severe large fiber damage and loss of protective sensation with either a 10-g monofilament or by testing vibration sensation with either a tuning fork or using biothesiometry as recommend by NICE . Furthermore, treatment is often limited to enhanced glycemic control and if pain is present, use of analgesic compounds with an efficacy of around 30% is very near to the efficacy of placebo treatment .

Over the last decades, the interest in small fiber neuropathy has increased mostly due to a growing agreement that it is detectable years in advance of large fiber damage . Unfortunately, early detection of small fiber neuropathy has proven to be a diagnostic challenge and is generally not carried out in clinical practice, as clinicians and researchers currently have no validated and robust clinical tests available, although several promising, and equipment-heavy, technologies are currently being developed . A number of composite neurological scores and questionnaires have also been developed and validated for clinical assessment of diabetic painful and painless neuropathy. Widely used are the Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument , the Neuropathy Disability Score , and the modified Toronto Clinical Neuropathy Score . Common for all is that they mostly aim at identifying or excluding the presence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and are less helpful in detecting improvement or worsening of the condition, perhaps particularly so in clinical practice. They are more widely used in clinical trials of diabetic neuropathies.

Detection and description of painful and painless peripheral neuropathy rely in clinical practice to a great deal on clinical observation and experience by the healthcare professional, guided by simple bedside tests such as monofilaments or biothesiometry occasionally adapting neuropathy impairment questionnaires. There exists an unmet need for high-sensitivity, high-specificity bedside tests and questionnaires for clinical use for the earliest possible detection of peripheral neuropathy.

Early detection and prevention

Early detection of diabetic peripheral neuropathy, painful and painless, remains a major challenge in clinical practice. Peripheral neuropathy is often first detected when permanent impairments and/or pain is already present . Current peripheral neuropathy screening relies on subjective tests of large fiber nerve function (light touch, vibration), sensory testing mainly . Small fiber testing (pain, temperature) is not routinely performed, although damage to small fibers appears to precede large fiber damage . In direct contrast, diabetic retinopathy and diabetic nephropathy have established screening detecting preclinical conditions and allowing preventative measures . Our clinical focus and practice are directed toward large fibers, although it has been clearly described that diabetic peripheral neuropathy, painful and painless, early on affects small unmyelinated fibers, which are responsible for pain perception, sweating, and blood flow, all crucial to diabetic foot ulceration and impairment of small fibers are believed to proceed large fiber . Adding to this, small fiber degeneration is found in prediabetes before the onset of type 2 diabetes .

Currently recommendations and conventional screening programs hamper the implementation of timely preventative measures in the individual person with diabetes and allow progression of complications. There is a clear need for robust and validated test methods and clinical endpoints to detect painful and painless peripheral neuropathy separately before it becomes clinically significant, and more so to target and focus on small fiber neuropathy as the location of earliest detectable neuropathy impairment . Theoretically, this could be a key to better compare and understand the associations, causative or reflective, between painful and painless neuropathies. But, most of all it could prove to be invaluable for early detection and prevention of peripheral neuropathy.

Similarities in treatment of painful and painless neuropathy

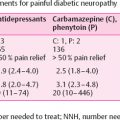

At present there are no disease-modifying treatments for diabetic peripheral neuropathy approved by the US food and Drug Administration or the European Medicines Agency, leaving optimization of glycemic control to prevent progression as the clinicians’ most important intervention. Several clinical trials have shown beneficial effect of tight glycemic control in preventing peripheral neuropathy in people with T1DM . The DCCT/EDIC study even demonstrated beneficial effect of intensified glycemic control years after terminating the intervention . For people with type 2 diabetes (T2DM), the evidence of beneficial effects of tight glycemic control in preventing painful and painless diabetic peripheral neuropathy is less convincing, but the varying results might arise from the fact that the many people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes might have gone unnoticed for many years prior to diagnosis. A small Japanese study demonstrated a relatively small beneficial effect of tight glycemic control , but several larger studies including the UKPDS, ACCORD, ADDITION, Steno 2, and VADT studies all failed to show significant results regarding diabetic peripheral neuropathy, although other microvascular complications improved. Previous clinical trials in both people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes have demonstrated beneficial effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mainly autonomic neuropathy but also on distal peripheral neuropathy in people with diabetes, although larger studies are still needed to confirm the findings . Also statins and fibrates have been shown to halt the progression of diabetic peripheral neuropathy , but might rarely induce neuropathy on their own . The implications for painful neuropathy on the interventions mentioned earlier are unknown. It is safe to say that treatment for painful neuropathy is solely directed toward symptom relief and improvement of quality of life as the main outcome measures. Unfortunately, almost all pharmacological agents have side effects with small therapeutic windows between beneficial effects and at times incapacitating side effects. The overall average efficacy of treatment is around 30% following guidelines and algorithms for use of drug classes . There is clearly a need for more efficient and safer treatment for painful neuropathy, but our limited understanding of the pathophysiology and interactions between painful and painless neuropathy prohibits the development of mechanism-based treatment options.

Deep sensory profiling and mechanism-based treatment in painful and painless neuropathy

While no disease-modifying treatment for painful diabetic neuropathy exists, several interesting agents are currently undergoing early clinical trial. These agents all target proposed mechanisms responsible for the onset of neuropathic pain, which classifies them alongside other pathogenetic drugs like α-lipoic acid, C-peptide, benfotiamine, aldose-reductase inhibitors, and the nerve growth factor-modulator Tanezumab . While none of these drugs have been approved by the US food and Drug Administration or the European Medicines Agency, some have achieved local authorization in some countries, as they have much milder side effects than their approved counterparts and have shown some effect in smaller studies although several different meta -analyses have proven them no better than placebo. However, if the disappointing results from the meta -analysis are indeed due to inefficient drugs or targets or if positive results are hidden, inside small subgroups remain unknown, as characterization of the type of pain (or painless polyneuropathy) critically is not a part of usual clinical trials. This issue would also become apparent even if some of the new agents might prove efficient in some people, as clinicians are still presented with the issue that they have no guidelines or indications weather a drug has any effect on their particular patient. Therefore future treatment of neuropathic pain, and probably also prevention of onset of diabetic peripheral neuropathy, should focus on personalized, mechanism-based medication/prevention arising from deep-sensory profiling and in-depth characterization of each individual with neuropathic pain or threatening neuropathy onset . Using this approach, researchers from the German Neuropathic Pain Research Network, EUROPAIN, and NEUROPAIN consortia applied their standardized protocol for Quantitative Sensory Testing in a large cohort of 902 participants . They then subgrouped them into three distinct groups using cluster analysis and identified the sensory profile of each subgroup. The subgroups consisted of (1) a group with loss of small and large fiber function alongside paradoxical heat sensation, (2) a group with preserved sensory function combined with heat and cold hyperalgesia and mild dynamic mechanical allodynia, and (3) a group with loss of small fiber function, pinprick hyperalgesia, and mechanical allodynia. Although the authors did not test the efficiency of different drugs in the three groups, they were able to replicate these sensory profiles in an experimental setting, generating one of the first models for mechanism-based treatment of neuropathic pain. Although this exact model is purely relevant for neuropathic pain and not for peripheral diabetic neuropathy in general, the basic ideas are very much relevant for future research of both painful and painless distal polyneuropathy and might also help distinguishing the two from one another.

When considering both treatment and prevention of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and neuropathic pain, diabetes type should also be taken into consideration as part of the deep phenotyping. It is apparent to most that the pathophysiological mechanisms for the development of distal diabetic polyneuropathy and neuropathic pain are hardly the same in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, although current clinical guidelines do not distinguish the two conditions from each other. From the fact that mild polyneuropathy is seen even in people with prediabetes, while it is more generally seen after years of disease in people with type 1 diabetes, it also becomes clear that one single mechanism might not fit to describe the natural history of the development of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and neuropathic pain. Chronic low-grade inflammation, oxidative stress, impaired perfusion, and accumulation of advanced-glycemic end products are all thought to be contributing factors to the development of diabetic peripheral neuropathy , but even a combination of these factors does not seem to give a clear picture of the natural history and even less so the differences between those who develop painful and painless neuropathy.

Another question that must be addressed when talking differences between the sensory profiles of those with painful and painless diabetes neuropathy is the cause of the pain. A prevailing theory is that the initial pain arises from damage to the peripheral nerve endings of the small nerve fibers (dying-back neuropathy) , but that persistent and chronic pain arises from central sensitization and altered brain plasticity rather than morphological changes in the peripheral nerves . With this in mind, people with distal peripheral diabetic neuropathy with and without pain might not even differ regarding their peripheral morphology, but instead differ in regard to their central interpretation of the missing or enhanced signals arising from the distal nerves. This theory is supported by the fact that primary nerve afferents are sensitized in painful diabetic neuropathy in rats, inducing dorsal horn hyperactivity and neuroplastic changes in central sensory neurons . Furthermore, the rather common occurrence of allodynia in people with painful diabetic neuropathy likewise supports the idea that central pain processing is indeed altered . The possible implications of this are huge, but nevertheless central sensibilization and brain plasticity are not considered or even less so implemented into any clinical guidelines or even designs for randomized controlled trials regarding diabetic peripheral neuropathy or neuropathic pain. This is mainly due to our lacking understanding of not only the processes of the central nervous system but also its interaction with the peripheral nerves. Functional changes in the pain-processing areas of the brain have, however, been linked to diabetic peripheral neuropathy and neuropathic pain at least in rodents, while the translation to human studies have been a bit less certain . Some studies in humans have linked diabetic peripheral neuropathy to increased activity of several brain areas including thalamus after peripheral thermal stimulation, while others have indicated marked reductions in levels of N -acetyl-aspartate in the same region with painless distal diabetic polyneuropathy . Therefore, to perform an in-depth sensory profiling precisely and adequately, and thus distinguish painful from painless diabetic peripheral neuropathy, future researchers might also need to consider the role of the central nervous system, although current research methodologies only allow glimpses into the complexity of the vast network of neurons that is the central nervous system.

In summary, deep-sensory profiling and mechanism-based prevention and treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and neuropathic pain are a huge field, which we have only just begun to explorer. Future research into the area is very much needed, and maybe even essential to achieve an understanding of diabetic peripheral neuropathy with and without pain, how they differ, and how they are alike. Furthermore, future randomized controlled trials and other clinical studies should build on the growing knowledge achieved by rather basal research into deep-sensory profiling and power accordingly to test the effect not only in a large population with neuropathic pain but also in subgroups with different proposed mechanisms of neuropathic pain.

Novel clinical endpoints and research methodologies

Despite a considerable number of new and promising methods for early detection of particularly small fiber neuropathy, but also large fiber neuropathy, the lack of well-established gold standard methods to validate novel methods against have led to the fact that both researchers and clinicians are yet to agree on and standardize the use of many of the newer methods . In order to perform meaningful clinical trials, the research community must first have access to agreeable, standardized, highly sensitive methods for quantification of nerve fiber function, so that a potentially beneficial effect of disease-modifying treatment can be detected. Novel methods and approaches are discussed elsewhere and comprise skin biopsies of small fiber nervous tissue combining form and function , cornea confocal microscopy for early detection in changes of small fiber morphology and pain perception thresholds, and ion-channel functionalities in small fiber diabetic neuropathy . Biofluid markers of neurodegeneration and inflammation , (deep) sensory phenotyping , genotyping, and epi-genetic description are all cutting-edge novel approaches for describing diabetic neuropathy—and fit nicely in with our wish for a better understanding of the pathophysiology. All is needed, in our opinion, not only to compare painful and painless neuropathies and describe neuropathy mechanisms, but also to develop efficient preventative agents, disease-modifying agents, and compounds to treat pain in diabetic neuropathy.

Perspectives

Comparing and describing associations between painful and painless diabetic peripheral neuropathy at this time is a relatively easy undertaking, as very little is known about associations in terms of pathophysiology, structures, functions, and mechanisms responsible for the development of these intercorrelated complex conditions.

At this time, it is not possible to detect, describe, and identify, which person with diabetes will progress to painful neuropathy, independent of the presence of painless neuropathy, which coexists in practically all cases. The way forward seems to be utilization of the list of novel high-tech methodologies mentioned earlier in order to construct robust clinical endpoints for description of the natural history, pathophysiology, and mechanism-based approaches—allowing not only successful clinical trials but also optimization of clinical practice in terms of early detection, prevention, diagnosis, and individualized treatment for painful and painless diabetic peripheral neuropathy.

References

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree