Fig. 4.1

Body weight and visceral adipose tissue mass are greater in sedentary OVX mice compared to age-matched sham mice. Increasing the cage activity of the OVX mice through access to a voluntary running wheel attenuated gains in visceral fat mass and resulted in minimal change in body weight. Data are expressed as percent change compared to age-matched sedentary sham group

Table 4.1

Food consumption in sham and OVX animals

Food consumption (g/day) | Feed efficiency (BW/g*kcal) | Feed efficiency (VF/g*kcal) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Sham-Sed | 5.21 ± 0.29 | 1.14 ± 0.007 | 5.34 ± 0.12 |

OVX-Sed | 4.38 ± 0.06* | 1.45 ± 0.007* | 4.22 ± 0.06* |

Sham-Exer | 5.12 ± 0.06 | 1.14 ± 0.005 | 5.11 ± 0.11 |

OVX-Exer | 4.37 ± 0.06* | 1.45 ± 0.005* | 4.14 ± 0.06* |

Fig. 4.2

Voluntary running distances of female OVX mice are lower than age-matched sham mice. Each point corresponds to distance run over 24 h

Development of Visceral Adiposity After Ovarian Ablation Leads to Lipolytic Dysfunction in Adipocytes and Fatty Acid Overflow

Under conditions of nutrient excess, free fatty acids (FFAs) are effectively removed from circulation and stored as triacylglycerol (TAG) in white adipose tissue. In contrast under conditions of energetic demand (i.e., exercise or starvation), FFAs are liberated from the stored TAG using a highly regulated enzymatic process termed “lipolysis.” Lipolysis is a sequential sequence of enzymatic reactions that result in the complete catabolic breakdown of stored TAG leading to the release of FFAs into circulation. However, in certain disease states, mechanisms that regulate anabolic storage or catabolic breakdown of TAG are disrupted, and these alterations appear to significantly contribute to the onset of metabolic disease. In our hands, OVX animals exhibit significant elevations in circulating FFA, which appears to be a result of increases in basal lipolysis in the visceral adipose tissue [9, 10]. The in vivo results are confirmed by measures of enhanced lipolytic activation in visceral adipose tissue from OVX animals compared to sham using adipose tissue organ bath setups and isolated adipocyte measures [10, 16]. Coupled with dysregulation of basal lipolysis is a poor induction of the lipolytic response in OVX animals [10, 16, 17]. It is clear that derangements in lipolytic function are a characteristic of visceral adipose tissue in OVX mice, with the alterations resulting in a moderate increase in circulating FFA and a poor ability to mobilize FFA under conditions of metabolic stress.

We have previously reviewed the mechanisms that appear to contribute to altered regulation of lipolytic function in the OVX animals [11, 18]. Briefly, our data suggest that OVX animals exhibit a significant increase in visceral adipose tissue glycerol lipase (ATGL) protein content compared to the sham animals [10, 17]. ATGL is the rate-limiting lipase in the catabolic breakdown of stored TAG, which likely explains the increased FFA release from adipose tissue in the OVX animals. The alteration in lipase content was coupled with a decrease in perilipin (PLIN1) and an upregulation of adipose differentiation-related protein (PLIN2) content in the OVX mice compared to the sham mice. PLIN1 is a lipid droplet (LD) coating protein that regulates lipolytic rate by preventing unstimulated lipolysis and by facilitating activated lipolysis, while PLIN2, even though in the same protein family, does not adequately protect the LD from unstimulated lipolytic attack nor does it encourage stimulated lipolysis [19]. These alterations in LD coating protein content are likely critical in explaining alterations in adipocyte function under conditions of reduced ovarian function. With the loss of ovarian function in the female mice, there are dynamic changes in critical signaling proteins that result in dysregulation of lipolytic control contributing to significant increases in circulating lipid under conditions of nutrient excess.

The ability of the adipocyte to continually expand to accommodate more lipid storage is limited; thus under conditions of constant excess nutrient consumption the rate of TAG storage will decline [20]. The inability to continue to sequester more lipid in the white adipose tissue is termed the “overflow hypothesis” (Fig. 4.3) [21]. This hypothesis suggests that increased fatty acid levels in circulation lead to enhanced ectopic fat storage in other tissues such as skeletal muscle and/or the liver. An inability to effectively store lipid, due to alterations in the regulatory control of TAG dynamics, increases the risk of developing various forms of lipotoxicity in peripheral tissue. Lipotoxicity is defined as the excessive accumulation of intracellular lipid in peripheral tissue that contributes to the development of cellular dysfunction. Lipotoxicity is most commonly linked to the development of peripheral insulin resistance. Thus, under conditions of ovarian dysfunction there are unique cellular alterations that develop in white adipose tissue that would be a critical contributor to the development of increased risk for type 2 diabetes.

Fig. 4.3

Disruption of ovarian function leads to development of the “overflow hypothesis” in visceral adipocytes

Skeletal Muscle Is a Primary Storage Depot for Excess Circulating Lipid Under Conditions of Reduced Ovarian Function

Skeletal muscle is known to act as a storage depot for lipid in the form of intramuscular triglycerides (IMTG). In 1999, Krssak et al. demonstrated a relationship between excessive accumulation of IMTG and the onset of insulin resistance in the muscle [22]. Investigations have attempted to pinpoint if the accumulation of lipid within the muscle cell plays a causative role in the development of insulin resistance; unfortunately the overall results remain equivocal. Although the exact mechanism has yet to be identified, current dogma suggests that elevation in stored lipid results in increased lipid-based molecules (i.e., ceramides) that are the likely contributors to the development of insulin resistance in skeletal muscle [23]. Using the OVX model, we have found across different skeletal muscle groups (i.e., plantaris, soleus, tibialis anterior, flexor digitorum brevis) an accumulation of a significant amount of intracellular IMTG compared to the sham group (Fig. 4.4). As in other models, this elevated amount of IMTG is associated with the development of glucose intolerance in the OVX mouse. The increase in IMTG in the OVX model is associated with increased protein content of the primary fatty acid transporters, CD36/FAT and FABPpm, in the skeletal muscle [24]. An increase in the protein content of these transporters would contribute to the elevated IMTG storage in the OVX model. As pointed out above, the OVX model results in a loss of regulatory control of lipolytic action in the visceral adipose tissue contributing to an increase in circulating FFAs. Based on the portal vein hypothesis, it would be expected that the triglyceride accumulation would develop in the liver potentially resulting in hepatic steatosis [25]; however our results did not entirely support this hypothesis [9]. A similar result has been found by another lab using the OVX mouse model [13]; however the development of hepatic steatosis is often found in the OVX rat model that may be a result of the transient hyperphagia that occurs in the rat [26, 27]. Collectively, these data suggest that the primary target of the increased circulating lipid in the OVX mouse model is the skeletal muscle and not the hepatic tissue. Thus, the development of overall peripheral insulin resistance in the OVX model is likely the result of a metabolic defect that is mediated in the skeletal muscle.

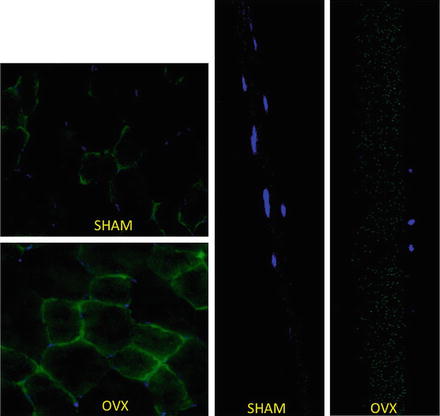

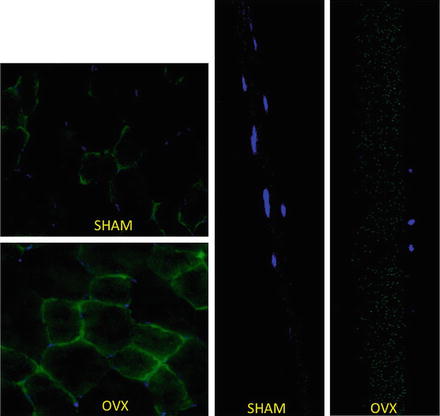

Fig. 4.4

Accumulation of intramuscular TAG in skeletal muscle fibers in OVX animals compared to age-matched sham animals. On the left are plantaris muscle cut in cross section and the right are single muscle fibers isolated from the flexor digitorum brevis. Lipid droplets are imaged using BODIPY (green) and nuclei (blue) as previously described [43]

Uncovering the Metabolic Mechanisms That Contribute to Increased IMTG Content and Onset of Insulin Resistance in Skeletal Muscle Under Conditions of Ovarian Dysfunction Remain Elusive

An often-implicated target for accumulation of IMTG is the mitochondria. Arguments have been made that the development of dysfunction within the mitochondria contributes to a reduced ability to utilize lipid, thus encouraging fatty acids to enter esterification and consequently storage [28]. However, many have argued that for this to happen one must ignore the energetic state of the cell; thus it is hard to reconcile that an inability to oxidize lipid is the primary or only deficit that is responsible for the development of insulin resistance in skeletal muscle [29]. In our hands, we have found that mitochondria in single skeletal muscle fibers from OVX animals consume pyruvate and palmitate with equal efficacy as muscle fibers from the sham animals [24]. The only detectable deficiency in oxygen consumption by the muscle fibers from OVX animals was under basal conditions or in a state of maximal uncoupling. These results are difficult to extrapolate to a physiological state since neither state exists within tissue of the animal. For example, the uncoupled state represents an artificial condition used to maximally challenge or stress the mitochondria and it is rare to find mitochondria operating in this condition [30]. In addition, we have found little evidence of loss of mitochondrial density within skeletal muscle from OVX animals [24]. At this point, it is unclear if a mitochondrial pathology develops in the OVX animal that would contribute to the resulting metabolic dysfunction seen in the animal.

As a means to identify a possible mechanism, we undertook an unbiased metabolic profiling approach to identify potential metabolic limitations within the skeletal muscle from OVX mice. We found a significant reduction in the long-chain acylcarnitines and short-chain acylcarnitines [24]. These data suggest a reduced flux of long-chain fatty acids through β-oxidation or a reduced transport of long-chain fatty acids into the mitochondria. With respect to the former, we have found no differences in the protein content of VLCAD, LCAD, and MCAD in skeletal muscle of OVX mice, which would suggest that enzymatic capacity of β-oxidation is not the limiting factor. However it should be noted that other labs have found these same enzymes to be estrogen sensitive [2]. With respect to the latter suggestion it is possible that the results suggest an inability to transport long-chain fatty acids into the mitochondria. Indeed, Campbell et al. found a reduction in carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT-1) activity in skeletal muscle from OVX rats compared to sham rats [31]. CPT-1 is the primary transporter of long-chain fatty acids into the mitochondria. These results suggest that the ovary influences lipid entry dynamics into the mitochondria through some undefined influence on CPT-1 or possibly some aspect of β-oxidation. Collectively, reductions in ovarian function result in increased lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle due to poor lipid entry into the mitochondria, which is a likely contributor to the development of peripheral insulin resistance.

Evidence Suggests That Estrogens Are Likely the Key Ovarian Hormone That Influences the Overall Metabolic Phenotype

Under conditions of reduced ovarian hormone function the subsequent increase in visceral fat mass in women increases their risk for developing metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Although the ovary secretes a number of different hormones current evidence would suggest that it is a form of estrogen, likely 17β-estradiol, which predominantly mediates these metabolic effects. For example, the use of estrogen therapy (ET) in women can attenuate increases in visceral fat mass observed in women following the menopausal transition [32]. In a similar fashion, chronic 17β-estradiol treatment of animal models after ovariectomy attenuates the development of visceral adiposity [10], but does not always completely abrogate all of the physiological alterations from developing. All of these “rescue” approaches suggest that 17β-estradiol is the necessary factor missing after ovariectomy; it should be noted that the redelivery approaches are not without limitations. Specifically, the doses of 17β-estradiol used are often supra-physiological and the manner in which they are delivered results in a sustained exposure of the dose rather than a cyclic exposure that is seen during the estrous cycle. Thus, it is possible that these redelivery approaches have just overwhelmed the system resulting in a pharmacological effect rather than a physiological effect. In addition, a number of these metabolic changes seen in the OVX model also develop in a similar fashion across genetically manipulated animal models. For example, genetic ablation of the estrogen receptor alpha or the aromatase enzyme results in adult-onset adiposity accompanied by the development of glucose intolerance [33, 34]. Interestingly, when comparing these genetic manipulated models a sex difference is often visualized with the male mice often exhibiting more severe metabolic dysfunction than the female mice [33], which might suggest that other female-specific hormones remain protective. Another critical point that should be considered in examining these data is that these mutant mice were born and developed in an environment of disrupted estrogen signaling; thus they never experience any form of estrogen exposure. Although this is a useful experimental approach it does not mimic clinical conditions found in humans; it is rare that a human would never experience some influence of estrogen exposure. In addition, due to the use of the global knockout approach the effects are not tissue specific; thus it is challenging to determine primary versus secondary effects, which is a problem that faces investigators using the OVX model. To overcome these limitations, investigators will need to develop tissue-specific knockout approaches to identify the true physiological role of the estrogen receptor in each tissue. Overall, the data suggest that the disruption of the estrogen signaling axis is likely the critical component to the development of these metabolic conditions; however it would be naïve not to consider the possibility that other ovarian derived hormones are important to peripheral tissue function as well.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree