Lung cancer classification is of paramount importance in determining the treatment for oncologic patients. Most lung cancers are non–small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLC), which are further subclassified into squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and large cell carcinoma. Lung neuroendocrine tumors are subclassified into typical carcinoid, atypical carcinoid, small cell carcinoma, and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. In NSCLC in particular, the histologic classification and tumor mutation analysis are central to today’s targeted therapy and personalized treatment. This article discusses the current diagnostic criteria for classification of NSCLC and lung neuroendocrine tumors and implications for oncologic treatment.

Lung cancer classification and prognosis have evolved with increasing knowledge of the biology of the disease and advances in therapy. The distinction of the histologic cell type of lung cancer is important for treatment and prognosis. Traditionally, the role of the pathologist has been to distinguish small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) from non–small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLC). However, with current therapies, the subclassification of NSCLCs, especially the distinction of adenocarcinoma from squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), has become important. The use of uniform terminology and diagnostic criteria enables accurate and reproducible diagnosis. This article discusses the current classification of NSCLCs and lung neuroendocrine tumors (NET) based on histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings and the clinical implications for oncologic therapy.

Non–small cell lung carcinomas

NSCLCs account for 75% to 85% of all lung cancers in the United States. There are three main types of NSCLC: (1) SCC, (2) adenocarcinoma, and (3) large cell carcinoma. Most patients present with advanced-stage disease at diagnosis, often necessitating medical treatment. The histologic type of NSCLC is important for selection of therapy. For example, premetrexed is more active in combination with cisplatin in the treatment of advanced adenocarcinoma and large-cell carcinoma of the lung than in the treatment of SCC. Another therapeutic agent, bevacizumab (Avastin), a vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody, is approved in combination with cystotoxic chemotherapy in the treatment of adenocarcinoma, but not SCC because of concern for life-threatening bleeding. Subclassification of NSCLC is thus necessary when possible and is aided by the use of immunohistochemical and mucin stains. In some cases, however, a specific cell type still cannot be identified because of poor differentiation or limited sampling; these tumors should be referred to as “NSCLC, not further classified.”

Squamous cell carcinoma

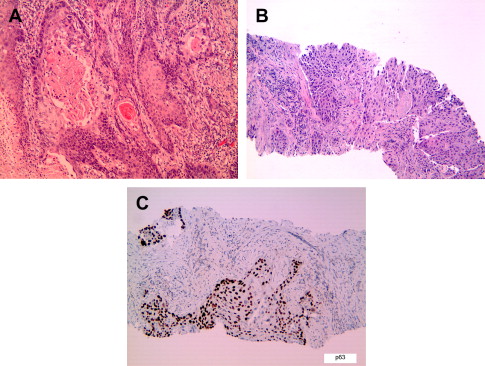

Although most lung cancers are known to be associated with cigarette smoking, the association is strongest for SCC, followed by small cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. SCCs predominantly occur in the large central airways but may also be seen in the small peripheral airways. Disease progression has been documented to occur in the airway epithelium in a step-wise fashion from dysplasia to carcinoma in situ to invasive carcinoma. Microscopically, these tumors show evidence of squamous differentiation in the form of intercellular bridges and keratinization ( Fig. 1 ). Invasive SCC is graded as well-, moderately, or poorly differentiated based on the degree of resemblance to normal squamous epithelium. Poorly differentiated SCC may be difficult to distinguish from poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, small cell carcinoma, or large cell carcinoma by morphology. In such cases, immunohistochemistry can be helpful to establish a diagnosis of SCC ( Table 1 ). Histologic variants of SCC include papillary, clear cell, small cell, basaloid, and alveolar space-filling type. The alveolar space-filling pattern, which has been described in peripheral SCC, seems to be a favorable prognostic indicator. The stage of disease and performance status at diagnosis, however, remain the most important prognostic indicators for survival. Stage for stage, the survival rate for SCC is better than for adenocarcinoma.

| Adenocarcinoma | Squamous Carcinoma | Large Cell Carcinoma | Lung Neuroendocrine Tumors a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroid transcription factor-1 | + | – | ± | + b |

| P63 | – | + | – | – |

| CK5/6 or34BE12 | – | + | – | – |

| Neuroendocrine markers c | – | – | – | + |

a Includes lung carcinoids, SCLC, and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

b Thyroid transcription factor-1 positivity is specific for lung origin for carcinoids but not for SCLC or large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

c Neuroendocrine markers include synaptophysin, chromogranin, and CD56.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Although most lung cancers are known to be associated with cigarette smoking, the association is strongest for SCC, followed by small cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. SCCs predominantly occur in the large central airways but may also be seen in the small peripheral airways. Disease progression has been documented to occur in the airway epithelium in a step-wise fashion from dysplasia to carcinoma in situ to invasive carcinoma. Microscopically, these tumors show evidence of squamous differentiation in the form of intercellular bridges and keratinization ( Fig. 1 ). Invasive SCC is graded as well-, moderately, or poorly differentiated based on the degree of resemblance to normal squamous epithelium. Poorly differentiated SCC may be difficult to distinguish from poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, small cell carcinoma, or large cell carcinoma by morphology. In such cases, immunohistochemistry can be helpful to establish a diagnosis of SCC ( Table 1 ). Histologic variants of SCC include papillary, clear cell, small cell, basaloid, and alveolar space-filling type. The alveolar space-filling pattern, which has been described in peripheral SCC, seems to be a favorable prognostic indicator. The stage of disease and performance status at diagnosis, however, remain the most important prognostic indicators for survival. Stage for stage, the survival rate for SCC is better than for adenocarcinoma.

| Adenocarcinoma | Squamous Carcinoma | Large Cell Carcinoma | Lung Neuroendocrine Tumors a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroid transcription factor-1 | + | – | ± | + b |

| P63 | – | + | – | – |

| CK5/6 or34BE12 | – | + | – | – |

| Neuroendocrine markers c | – | – | – | + |

a Includes lung carcinoids, SCLC, and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

b Thyroid transcription factor-1 positivity is specific for lung origin for carcinoids but not for SCLC or large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

c Neuroendocrine markers include synaptophysin, chromogranin, and CD56.

Adenocarcinoma

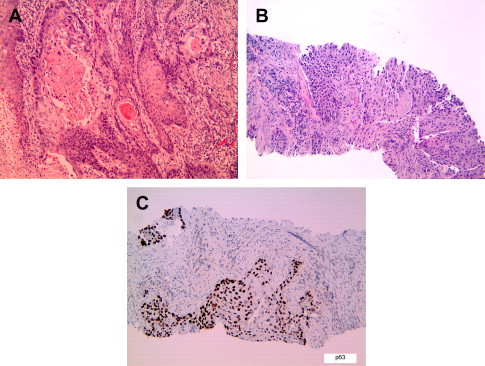

In recent decades, lung adenocarcinoma has surpassed SCC as the dominant histologic subtype of lung cancer for men and women in North America, likely because of changes in smoking habits and a true increased incidence of adenocarcinomas. Worldwide, adenocarcinoma is the most common histologic type in women, nonsmokers, and Asians. Adenocarcinomas may show variable patterns of lung involvement. They commonly occur as peripheral solitary masses but can also arise in the central airways or present as lobar consolidation, diffuse bilateral disease, or rarely pleural thickening mimicking malignant mesothelioma. Microscopically, adenocarcinomas show glandular differentiation or mucin production ( Fig. 2 ). The main growth patterns are acinar, papillary; bronchioloalveolar (lepidic); and solid with mucin. Most lung adenocarcinomas show a mixture of these patterns. The recognition of solid adenocarcinoma with mucin requires detection of cytoplasmic mucin by a mucin stain. Because focal mucin can be seen in squamous cell and large cell carcinomas, the World Health Organization (WHO) classification requires detection of mucin in at least five tumor cells in each of two high-power fields (HPF) for the diagnosis of solid adenocarcinoma with mucin (see Fig. 2 C, D). Similar to SCCs, lung adenocarcinomas are graded as well-, moderately, or poorly differentiated. The use of immunohistochemical and mucin stains can help to distinguish lung adenocarcinoma from poorly differentiated SCC and metastases to lung (see Table 1 ; Table 2 ). Rare histologic variants of lung adenocarcinoma include fetal; mucinous (colloid); mucinous cystadenocarcinoma; signet ring-cell; and clear cell carcinoma. A micropapillary pattern, characterized by papillary tufts without fibrovascular cores, is associated with aggressive behavior and poor prognosis, particularly for early stage disease (see Fig. 2 F). Although not currently part of the WHO classification (2004), micropapillary adenocarcinoma is proposed as a distinct subtype of lung adenocarcinoma in the new international multidisciplinary classification.

| CK 7 | CK20 | |

|---|---|---|

| NSCLC, breast carcinoma, gynecologic tract carcinoma | + | – |

| Colonic adenocarcinoma | – | + |

| Prostatic, renal cell, and hepatocellular carcinoma | – | – |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, mucinous ovarian, and mucinous bronchoaveolar lung carcinoma | + | + |

A number of recent articles suggest that lung adenocarcinomas with mixed histology should be classified according to their predominant histologic pattern with mention of minor histologic patterns, because these subtypes may have distinct clinical behavior and molecular associations. For example, bronchioloalveolar, papillary, and micropapillary subtypes have been found to be more likely than other subtypes to be associated with the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations. However, the solid subtype tends to lack EGFR mutation and is also associated with adverse prognosis.

Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma

Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC) is a subtype of lung adenocarcinoma and is defined by the WHO classification as an adenocarcinoma with bronchioloalveolar pattern and no evidence of stromal, vascular, or pleural invasion. Thus, strictly defined, BACs are rare, but the BAC (lepidic) pattern is commonly seen at the periphery of mixed-pattern adenocarcinomas. A diagnosis of BAC cannot be established on small biopsies, because complete sampling of the tumor on resected specimens is needed to exclude invasion.

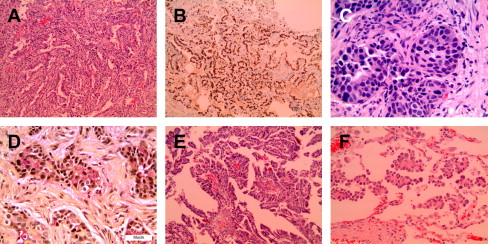

BACs disproportionally affect nonsmokers, women, and Asians. They can present as a peripheral solitary mass, multiple nodules, or a diffuse infiltrate (pneumonic pattern) simulating lobar pneumonia. Multiple lobes and bilateral lungs can be involved. Microscopically, BACs are classified as nonmucinous and mucinous ( Fig. 3 ). Nonmucinous BAC is composed of a proliferation of cuboidal neoplastic cells growing along intact alveolar walls, whereas the mucinous-type is lined by tall columnar mucinous epithelium. The nonmucinous-type is more common, more frequently solitary, and frequently harbors EGFR mutations. In contrast, the mucinous-type more commonly presents with pseudopneumonic infiltrates and is associated with KRAS rather than EGFR mutations. Mucinous BACs tend to have a worse prognosis than the nonmucinous-type; however, the clinical pattern and stage are the most important prognostic factors for survival. Pneumonic pattern is associated with worse survival than solitary or multifocal disease. The 5-year survival is greater than 80% for stages I and II and approximately 60% for higher-stage disease. Despite the tendency for intrathoracic recurrence and spread, the behavior of BAC is more indolent than that of conventional adenocarcinoma. It should be noted that previous studies on BACs may have included cases that are actually invasive adenocarcinomas with predominant bronchioloalvoelar pattern.

Studies have shown that patients with solitary adenocarcinoma with either pure lepidic growth (pure BAC) or predominantly lepidic growth with less than 5 mm invasion (minimally invasive adenocarcinoma) have 100% survival after complete resection. Based on these findings, the new international multidisciplinary classification proposes the new concepts of adenocarcinoma in situ (for BAC) and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (for predominant BAC pattern with <5 mm invasion). These new concepts are, however, not part of the current WHO classification.

BAC is distinguished from atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) by size: AAH is less than 0.5 cm. BAC and AAH are, otherwise, histologically similar and their distinction may not be possible on small biopsies. AAH is a frequent incidental finding in lung resections for adenocarcinomas and is recognized as a putative precursor of adenocarcinoma.

Large cell carcinoma

Large cell carcinoma is defined in the WHO classification as an undifferentiated non–small cell carcinoma lacking cytologic and architectural features of small cell carcinoma and showing no glandular or squamous differentiation. Large cell carcinoma accounts for approximately 9% of all lung cancers. These tumors tend to occur in the peripheral lung and tend to be large (>5 cm) and bulky. Microscopically, large cell carcinomas are comprised of large cells with round to irregular nuclei with vesicular chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and variably distinct cytoplasmic borders. The tumor cells are arranged in aggregates or sheets with frequent tumor necrosis. This diagnosis should be reserved for resected specimens wherein one can exclude squamous or glandular differentiation. Variant types of large cell carcinoma include large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC), combined LCNEC, basaloid carcinoma, lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma with rhabdoid phenotype. LCNEC is recognized as a distinct entity and is discussed separately in the section on lung NET.

Basaloid variant of large cell carcinoma, rhabdoid phenotype, LCNEC, and combined LCNEC all have worse prognosis than classic large cell carcinoma. Rhabdoid phenotype has been described not only in large cell carcinoma but also in sarcomatoid carcinoma and adenocarcinoma and is associated with aggressive behavior in all these tumors. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas, described mostly in Chinese patients, tend to present in early stage and have better prognosis than conventional NSCLC. These tumors are associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection in Asians but not in whites.

Other NSCLC types

Adenosquamous carcinomas represent less than 5% of all lung cancers. These tumors show components of both SCC and adenocarcinoma with each comprising at least 10% of the tumor. Most are located in the lung periphery. The behavior is more aggressive than either adenocarcinoma or SCC.

Sarcomatoid carcinomas account for approximately 1% of lung cancers. These tumors are defined by the WHO as a group of poorly differentiated non–small cell carcinomas that contain a component of sarcoma or sarcoma-like differentiation. This category includes tumors that have been variously termed pleomorphic carcinoma, spindle cell carcinoma, giant cell carcinoma, carcinosarcoma, and pulmonary blastoma. These tumors are thought to represent epithelial neoplasms that have undergone divergent sarcomatous differentiation. Although sarcomatoid features may be seen on a needle biopsy or cytology specimen, a diagnosis of sarcomatoid carcinoma may not be possible until after complete evaluation of the tumor on a resected specimen. The use of immunohistochemical stains, such as cytokeratins and EMA, can help identify the epithelial component of these tumors. Most cases of sarcomatoid carcinoma are in men with a history of heavy smoking. The upper lobes are preferentially involved. The pattern of metastasis is similar to NSCLC, but the behavior is more aggressive than conventional NSCLC.

Salivary gland type tumors of the lung represent less than 1% of all lung cancers. Subtypes include mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma, and epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma. These tumors tend to arise in the central airways. No predilection for gender or association with cigarette smoking or other risk factors has been found. The behaviors of these tumors are dependent on the grade and stage.

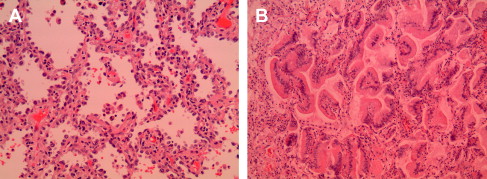

Lung NETs

In the current WHO classification, lung NETs are placed into four categories: (1) typical carcinoid (TC), (2) atypical carcinoid (AC), (3) SCLC, and (4) LCNEC ( Table 3 ). A three-tiered grading system is also applicable: low grade (= TC); intermediate grade (= AC); and high grade (= LCNEC and SCLC). Microscopically, these tumors all exhibit varying degrees of neuroendocrine morphology in the form of organoid nests, palisading, trabecular growth, and rosette-like structures ( Fig. 4 ). The main distinguishing features for the different NET types are mitotic activity and the presence or absence of necrosis.