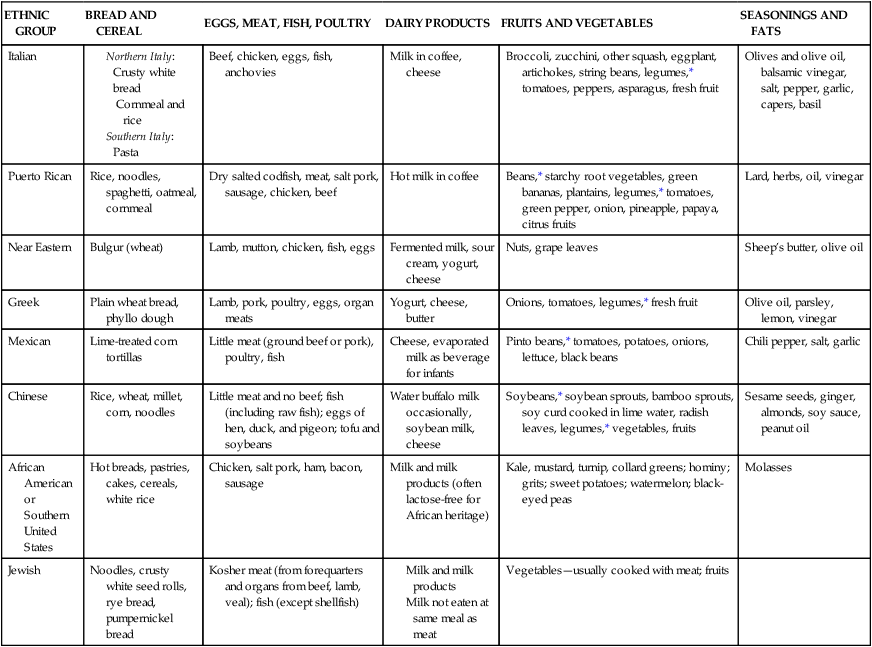

After completing this chapter, you should be able to: • Define terms used in the study of nutrition. • Identify biopsychosocial influences on nutritional intake and health. • Evaluate a daily diet for moderation, variety, and balance. • Explain the significance of nutrition labeling. • Recognize and differentiate among the various food guides available. • Discuss the role of the health care team. • Discuss interviewing and counseling strategies. • Explain strategies to serve as a change agent in the promotion of positive eating habits. • Describe the nutrition care planning process. • Identify your personal strengths and weaknesses in nutrition knowledge and its application. More recent terms used to discuss medical genealogy are nutrigenetics, related to how genetic predisposition affects susceptibility to diet, and the opposite, nutrigenomics, which addresses how diet influences gene expression and metabolism (Kussmann and colleagues, 2006). Nutrigenomics is aimed at individualized nutrition guidance for health and prevention of disease. Environmental forces affect food choices. In tandem with genetic predisposition, various health conditions can develop. Traditional food habits that are not commonly followed anymore by most Americans include eating wild greens like dandelion and burdock greens, other wild plants such as cattails, eating organ meats, or consuming a variety of seafood, including sardines and herring. The homogenization of the typical diet with chain restaurants offering the same foods throughout the country, and in some cases the world, along with reduced numbers and varieties of foods potentially is contributing to various health conditions. This is likely due to excess kilocalorie (kcalorie or kcal) intake from large portions with excess fats and sugars, and reduced diet quality from limited intake of a variety of vitamins and minerals (see Chapter 3). In the second half of the twentieth century, the focus shifted to prevention of chronic disease and dietary excesses. Meal-planning guides began in the 1940s when there were seven recommended food groups, butter being one of them as a vitamin D source. By the 1950s, when the baby-boom generation was being born, the Basic Four Food Groups classification (meat, grains, dairy, and vegetables and fruits) was developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to replace the older concept of seven food groups. Because milk was now being fortified with vitamin D, the advice for butter consumption was no longer recommended. The 1960s brought the research that indicated heart disease could be prevented with less saturated fat. Eventually, in 1990 the USDA replaced the Basic Four with the Food Guide Pyramid with the message that less meat and fats was desirable. In 2005 the new MyPyramid was developed. The updated version includes an online resource at MyPyramid.gov that provides individualized guidance. The current food guidelines recognize the importance of lifestyle as well as food and nutrition choices. 1. A nutrient is a chemical substance that is present in food and needed by the body. The macronutrients include the energy nutrients carbohydrate, fat, and protein. The micronutrients include vitamins, minerals, and water. A food high in nutrient density is one that has a high proportion of micronutrients in relation to the macronutrients. Empty kcalories implies the opposite. 2. Nutrition is the science of the processes by which the body uses food for energy, maintenance, and growth. Good nutritional status implies appropriate intake of the macronutrients—carbohydrates, proteins, and fats—and the various vitamins and minerals often referred to as “micronutrients” because they are needed in small quantities. If there is good digestion, absorption, and cellular metabolism of these nutrients in the diet, a person can generally achieve good nutritional status. 3. Malnutrition or poor nutritional status is a state in which a prolonged lack of one or more nutrients retards physical development or causes the appearance of specific clinical conditions (anemia, goiter, rickets, etc.). This may occur because the diet is poor or because of a digestion and metabolism problem. Excess nutrient intake creates another form of malnutrition when it leads to conditions such as obesity, heart disease, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. 4. Optimal nutrition status means that a person is receiving and using the essential nutrients to maintain health and well-being at the highest possible level. 5. A kilocalorie (kcalorie or kcal) is a unit of measure used to express the fuel value of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. The large Calorie (or kcalorie) used in nutrition represents the amount of heat necessary to raise the temperature of 1 kg of water 1° C. One pound of body fat equates to 3500 kcal. Carbohydrates, proteins, fats, and alcohol are the only sources of kcalories. One kcalorie equals approximately 4 kilojoules (kj) in the metric system. 6. Health is currently recognized as being more than the absence of disease. High-level health and wellness are present when an individual is actively engaged in moving toward the fulfillment of his or her potential. The art of nutrition includes the application of nutrition science to meet individual needs for the goal of optimal health status. 7. Public health is the field of medicine that is concerned with safeguarding and improving the health of the community as a whole. Public health nurses may work out of public health departments or private health organizations. Other public health programs have been developed for various population groups such as women who are pregnant or the elderly (see Chapter 14). 8. Holistic health is a system of preventive medicine that takes into account the whole individual. It promotes personal responsibility for well-being and acknowledges the total influences—biologic, psychologic, and social—that affect health, including nutrition, exercise, and emotional well-being. 9. Medical nutrition therapy (MNT) (referred to in the past as “diet therapy”) is the treatment of disease through nutritional therapy by registered dietitians (RDs). RDs are uniquely qualified to provide MNT because of their extensive training in food composition and preparation, nutrition and biochemistry, anatomy and physiology, as well as life-cycle concerns and disease states. MNT may be necessary for one or more of the following reasons: • To maintain or improve nutritional status • To improve clinical or subclinical nutritional deficiencies • To maintain, decrease, or increase body weight • To rest certain organs of the body • To eliminate particular food constituents to which the individual may be allergic or intolerant • To adjust the composition of the normal diet to meet the ability of the body to absorb, metabolize, and excrete certain nutrients and other substances Sound nutrition begins before birth, through the influence of food culture and exposure to food flavors through amniotic fluid in utero. Persons of various cultural communities consume differing types and amounts of foods. (See Table 1-1 for common and regional food habits.) The family later affects the growing child’s meal environment and exposure to food. Table 1-1 In the ideal scenario the infant is exposed to a variety of foods and is fed in a manner that promotes positive meal association. Then the infant is more likely to become a child who learns to like a variety of foods that are of high quality and dense in nutrients. When a child has been allowed to eat on the basis of his or her own hunger and satiety cues in a positive meal environment, eating takes place according to growth needs; thus an appropriate quantity of food intake is maintained. (See Chapter 12 for more detailed information on child development and nutritional needs.) Biopsychosocial concerns address the interplay between external environmental (psychologic and social factors) and internal forces (genetic or biochemical/physiologic requirements). For example, the diagnosis of diabetes is primarily a biochemical or internal problem, but for the person hearing this diagnosis it involves psychologic issues of acceptance versus denial and anger and social concerns of healthy living in an environment that may be stressful and that discourages adherence to a healthy diet (external problems or social forces). The biochemical problem of either very high or very low blood sugars can also affect emotions and the ability to think. Another relatively common physical condition adversely affecting food choices and nutritional status is lack of teeth. One study found that with the loss of 14 teeth or more there was significantly lower intake of salad vegetables. This was found to result in lower blood levels for vitamins A and C and the B vitamin folate (Nowjack-Raymer and Sheiham, 2007). • Economic (inadequate money to purchase food, limited finances for transportation to grocery stores such lack of a car or limited funds for gasoline) • Physical (lack of food storage and cooking facilities, physical impairments that inhibit consumption of a variety of foods or ability to travel to grocery stores) • Cultural (lack of exposure to a variety of foods because of limited parental offerings or overemphasis on excess intake with large portions of food in restaurants or at home) • Ecologic (droughts, floods, earthquakes, snow and ice storms) • Emotional (television advertisements and other media depicting nonnutritious foods as appealing and healthy foods such as spinach as unappealing) • Religious (adherence to restrictive food codes, religious food celebrations) • Political (food boycotts, forced starvation for military purposes) One factor influencing food choices is availability and food costs found in supermarkets. This can have significant impact on lower-income families. It was found among supermarkets in the Sacramento and Los Angeles areas of California that the cost of a market basket meeting the 2005 Dietary Guidelines was less than the food stamp allotment of the Thrifty Food Plan (see Chapter 14). However, it was estimated to require a low-income family to spend about half of their food budget on fruits and vegetables to meet the Dietary Guidelines (Cassady, Jetter, and Culp, 2007). The situation can be more problematic in nonurban areas. One study found in a rural setting that there are primarily convenience stores, rather than the larger supermarkets. Less than half of convenience stores carried low-fat milk and high-fiber bread, with prices significantly higher than less-healthy choices (Liese and colleagues, 2007). As restaurant eating has increased in frequency, there have been a variety of effects on this nation’s health. One issue is increased portion sizes. Gone are the days of 4-oz juice glasses, with the exception of old-time diner type of restaurants or those juice glasses found in antique stores. Consuming soft drinks (also referred to as soda pop, pop, and carbonated beverages) that have similar kcalories as fruit juice is now commonplace in restaurants and other food venues. A small soft drink can be 32 oz in some locations (Figure 1-1). Data from the nationally representative Nationwide Food Consumption Surveys and the NHANES found the percentage of calories from beverages virtually doubled between 1965 and 2002, equating to an increase of almost 250 kcal daily (Duffey and Popkin, 2007). This increased kcalories of beverages does not appear to be due to milk intake because, on average, preschool children were found to drink less than the 2 cups of milk recommended for children by the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Some excess kcalories for children does come from the butterfat content of milk because less than 10% of older children were found to drink low-fat or skim milk as advised for children over 2 years of age (O’Connor, Yang, and Nicklas, 2006). Family composition and changing roles can influence food choices. Increasing numbers of men are now shopping for and preparing food (Figure 1-2). Households composed of single persons are growing, with an increased demand for more ready-to-use foods, which are often high in fat and salt. Changes in diets are occurring around the world. Some are for the good with various types of cross-cultural cuisine. On the other hand, the so-called Western diet, which is high in saturated fat and sugar and low in fiber, is having an adverse effect on the health of populations around the world. Rates of obesity are increasing at alarming rates worldwide as food habits are changing. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that at least 1 billion people worldwide are overweight and 300 million are obese. See Chapter 14 for more on international nutrition concerns and programs. Two religious groups that forgo consumption of meat and other animal products are Seventh-Day Adventists and Hindus. Many persons of the Jewish faith adopt a vegetarian eating plan to help them follow a kosher diet. Others follow vegetarian diets for health, political, cultural, or economic reasons or a combination of these. Some athletes adopting a vegetarian diet may be masking a disordered eating pattern (see Chapter 12). If a vegetarian diet results in excess weight loss, a referral to a psychologist or eating disorder clinic may be necessary. The vegan diet is increasingly becoming popular. This form of vegetarian diet excludes all animal food sources, including no fish, eggs, or dairy products. For this reason it is far more difficult to meet nutritional needs with the diet. It was once thought in the 1970s, as written in the well-known book Diet for a Small Planet by Frances Moore Lappe, that protein combinations were required within the same meal. It is now known that if complementary protein sources are included within a 24-hour period that protein needs can be met (see Chapter 2). Common nutrient deficiencies with the vegan diet include iodine, vitamin B12, iron, calcium, zinc, riboflavin, and vitamin D. Because meat provides protein, a variety of B vitamins, and minerals, alternative foods high in these nutrients need to be included in the vegetarian diet for health (see Table 1-2, Box 1-1, Chapters 2 and 3). Table 1-2 Food Sources for Important Nutrients in the Vegetarian Diet There are potential benefits of following a vegetarian diet. Reduced heart disease can occur with reduced saturated fat from the exclusion of red meat. However, low saturated-fat intake, such as with use of low-fat milk products, remains important. A social impact is reduced armpit body odor (Havlicek and Lenochova, 2006). The traditional Mediterranean diet is based on beans and greens. Vegetables and grains are key elements of the Mediterranean diet. Beans and nuts are regularly consumed, and both are good sources of protein. The consumption of lean red meat historically was limited to a few times per month and fish to about once per week. The amount of cheese used historically has been moderate. Sweets are eaten in small amounts on special occasions only. Olives and olive oil are used liberally, but they are low in saturated fat and cholesterol free (see Chapters 2 and 7). Table 1-1 shows how the food groups of the MyPyramid Food Guidance System are incorporated into different types of eating patterns. A typical day’s diet for any ethnic, regional, or religious group may be evaluated nutritionally by checking it against an acceptable meal plan such as the MyPyramid Food Guidance System. It is the position of the American Dietetic Association that the total diet or overall pattern of food eaten is the most important emphasis of a healthful eating style. The value of a food should be determined within the context of the total diet because classifying foods as “good” or “bad” may foster unhealthful eating behaviors (Nitzke and Freeland-Graves, 2007). Persons of various cultures eat at fast-food restaurants (Figure 1-3). As long as an individual remembers the goals of balance, variety, and moderation, fast-food meals can safely be included in the diet (Box 1-2). Healthy meal choices can be found on fast-food menus. Fast foods can meet nutrient-density criteria and the Dietary Guidelines if chosen wisely. Serving sizes are important. See Appendix 1 on the Evolve website for websites of fast-food restaurants where kcalorie and nutrient analysis can be obtained. • Focus on smaller portions of meat and cheese dishes; avoid “super-sizing.” • Remove the skin from cooked chicken. • Look for bean-based dishes and salads or other vegetables or fruits. • Choose a small or low-sugar beverage or low-fat milk. • Ask for salad dressing on the side to help control the quantity. Mandatory nutrition labeling went into effect in 1994 with the goal of helping consumers adhere to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (see the following section). The change is aimed at reducing the prevalence and complications of chronic illnesses, such as heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes (see Chapters 7 and 8). Nutrition labeling is a valuable tool for learning to apply nutrition information in a practical way. A health-conscious shopper uses the percentages shown on the label to determine how well each serving of the food fulfills recommended nutritional requirements. For example, if one serving of a food has 25% of a particular nutrient listed, it means that each serving is good for one fourth of a person’s recommended daily intake for that nutrient. Ingredients are still listed in order of content in a product. If sugar is listed as the first ingredient, the amount of sugar in the product is greater than the amount of any of the other ingredients. It is easy now to quantify exactly how much is included in a serving of food. For example, 1 tsp of sugar equates to 4 g on the food label; therefore a can of a soft drink containing 40 g of sugar contains the equivalent of 10 tsp of sugar. Consumers need to learn how to interpret food labels (Figure 1-4). To help the consumer calculate the kcalories in a given food, the food label on larger food packages also lists the conversion factor to change grams into kcalories—that is, fat 9, carbohydrate 4, protein 4 (refer also to Chapter 2). Therefore 1 tsp of sugar contains 16 kcal (4 g carbohydrate multiplied by 4). See Chapter 2 for kcalories from alcohol. A relatively new addition on food labels is the amount of trans fats. Trans fats are found in hydrogenated fats and shortenings. This type of fat is now known to contribute to cardiovascular disease (see Chapter 7). The health claims that can be made on food labels under the labeling law are as follows: • Foods high in fiber may reduce the risk of cancer and heart disease. • A low-fat diet may reduce the risk of cancer and heart disease. • A low-sodium diet may help prevent high blood pressure. • Foods high in calcium may help prevent osteoporosis. • Folate leads to decreased neural tube defects. • Sugar alcohols reduce dental caries. Daily Reference Values (DRVs), generally referred to as Daily Values (DVs), is a term developed for food labels. The percentage of DVs for the marker nutrients vitamins A and C and the minerals calcium and iron can be found on food labels (see Figure 1-4).

The Art of Nutrition in a Social Context

INTRODUCTION

WHAT ARE THE BASIC TERMS TO UNDERSTAND IN THE STUDY OF NUTRITION?

HOW DO FOOD AND DIETARY PATTERNS DEVELOP?

ETHNIC GROUP

BREAD AND CEREAL

EGGS, MEAT, FISH, POULTRY

DAIRY PRODUCTS

FRUITS AND VEGETABLES

SEASONINGS AND FATS

Italian

Beef, chicken, eggs, fish, anchovies

Milk in coffee, cheese

Broccoli, zucchini, other squash, eggplant, artichokes, string beans, legumes,* tomatoes, peppers, asparagus, fresh fruit

Olives and olive oil, balsamic vinegar, salt, pepper, garlic, capers, basil

Puerto Rican

Rice, noodles, spaghetti, oatmeal, cornmeal

Dry salted codfish, meat, salt pork, sausage, chicken, beef

Hot milk in coffee

Beans,* starchy root vegetables, green bananas, plantains, legumes,* tomatoes, green pepper, onion, pineapple, papaya, citrus fruits

Lard, herbs, oil, vinegar

Near Eastern

Bulgur (wheat)

Lamb, mutton, chicken, fish, eggs

Fermented milk, sour cream, yogurt, cheese

Nuts, grape leaves

Sheep’s butter, olive oil

Greek

Plain wheat bread, phyllo dough

Lamb, pork, poultry, eggs, organ meats

Yogurt, cheese, butter

Onions, tomatoes, legumes,* fresh fruit

Olive oil, parsley, lemon, vinegar

Mexican

Lime-treated corn tortillas

Little meat (ground beef or pork), poultry, fish

Cheese, evaporated milk as beverage for infants

Pinto beans,* tomatoes, potatoes, onions, lettuce, black beans

Chili pepper, salt, garlic

Chinese

Rice, wheat, millet, corn, noodles

Little meat and no beef; fish (including raw fish); eggs of hen, duck, and pigeon; tofu and soybeans

Water buffalo milk occasionally, soybean milk, cheese

Soybeans,* soybean sprouts, bamboo sprouts, soy curd cooked in lime water, radish leaves, legumes,* vegetables, fruits

Sesame seeds, ginger, almonds, soy sauce, peanut oil

African American or Southern United States

Hot breads, pastries, cakes, cereals, white rice

Chicken, salt pork, ham, bacon, sausage

Milk and milk products (often lactose-free for African heritage)

Kale, mustard, turnip, collard greens; hominy; grits; sweet potatoes; watermelon; black-eyed peas

Molasses

Jewish

Noodles, crusty white seed rolls, rye bread, pumpernickel bread

Kosher meat (from forequarters and organs from beef, lamb, veal); fish (except shellfish)

Vegetables—usually cooked with meat; fruits

WHAT ARE BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL CONCERNS IN HEALTH CARE?

HOW DO CULTURAL AND SOCIETAL FACTORS INFLUENCE NUTRITIONAL INTAKE?

CHANGING FOOD HABITS

VEGETARIAN DIETS

NUTRIENT

SOURCES

Calcium

Milk and milk products, particularly cheese and yogurt; fortified soy milk; dark green leafy vegetables such as parsley, kale, mustard, dandelion, and collard greens

Iron

Legumes, dark green leafy and other vegetables, whole-grain or enriched cereals or breads, some nuts, and dried fruits (many factors may affect absorption of this nutrient)

Riboflavin (vitamin B2)

Milk, legumes, whole grains, and certain vegetables

Vitamin B12

Milk and eggs, fortified soybean milk, fortified soy products, Marmite

Zinc

Nuts, beans, wheat germ, and cheese

Protein

Eggs, milk, nuts and seeds, legumes, especially soybeans and tofu

COMMON ETHNIC EATING HABITS

Chinese

Mediterranean Region

WHAT IS THE MEANING OF MODERATION, VARIETY, AND BALANCE?

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF FOOD GUIDES IN GOOD NUTRITION?

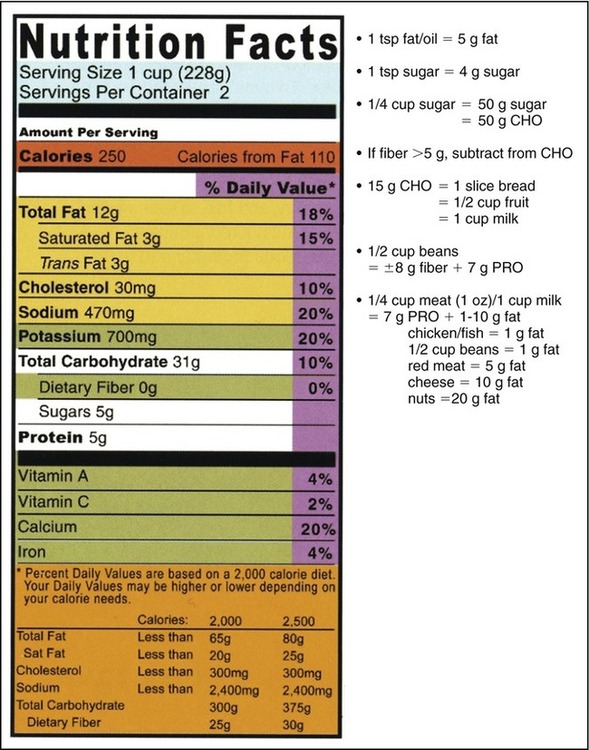

NUTRITION LABELING

DAILY REFERENCE VALUES

The Art of Nutrition in a Social Context

Nutritious Menu for a Vegan Diet

Nutritious Menu for a Vegan Diet

Nutritious Menu Including Fast Food

Nutritious Menu Including Fast Food