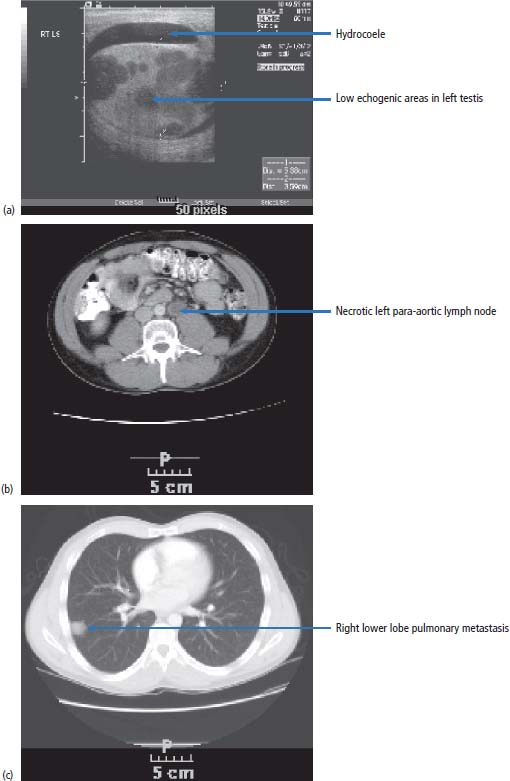

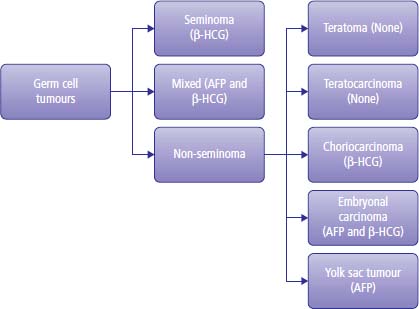

15 Testicular cancer is one of the few solid cancers in adults that may be successfully cured even in the presence of metastases. This has only been achievable in the last 40 years, since the introduction of cisplatin chemotherapy. Cisplatin was discovered serendipitously by Barnett Rosenberg, a physicist at Michigan State University, in 1965. He studied the effects of electric currents on Escherichia coli using platinum electrodes in a water bath and found that they stopped dividing but not growing, leading to bacteria up to 300 times longer than normal. This was found to be due to cisplatin, a product from the platinum electrodes, which was interfering with DNA replication. Following this, Professor Sir Alexander Haddow, the then head of the Chester Beatty Institute in London, showed that cisplatin was active against melanoma in mice, and clinical trials with human patients began in 1972. The treatment of testis cancer represents one of the major and wonderful triumphs of oncology. The application of modern treatments has led to a fall in death rates by 70% over the last 10–15 years, and in 2011 only 68 men died of this condition in the United Kingdom compared to over 2207 patients that were diagnosed (Table 15.1). A number of factors have been shown to increase the risk of developing testicular cancer: There have been significant advances in the understanding of the molecular biology of adult male germ cell tumours. It is over 15 years since the original identification of the characteristic cytogenetic marker of adult male germ cell tumours: isochromosome 12p. An extra copy of chromosome 12p is present in 85% of all tumours, and in the remaining percentage there are tandem duplications embedded at other chromosomal locations. The cyclin D2 gene, which is concerned with the regulation of the cell cycle, is mapped to this area. This suggests that the aberrant expression of cyclin D2 leads to the dysregulation of the normal cell cycle and tumour development. This abnormality is present in both seminoma and teratoma. Testicular tumours also express c-KIT, stem cell factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) α-receptor gene. Mutations in the KIT gene occur in 8% of all testicular germ cell tumours but are seen in 93% of patients with bilateral disease. These changes in the KIT gene appear to be specific to seminoma. These molecular findings suggest possible therapeutic options. Table 15.1UK registrations for kidney cancer 2010 Media campaigns have led to public awareness of testicular cancer as a curable condition and of the importance of early diagnosis. Generally, patients noticing testicular masses present to their GPs and are referred immediately to urology outpatients. There remain, however, a number of alarming instances where GPs have treated patients with testicular tumours for epididymitis rather than referring them on. Patients with teratoma present during the second and third decades of their lives, generally with swelling of the testes and less frequently with pain. Men with seminoma may present in their third to fifth decades. Men with testicular cancer may have gynaecomastia. This is due to the production of steroid hormones by the malignancy and clearly not to α-fetoprotein (AFP) or human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) synthesis. Around 30% of patients with testicular cancer are oligozoospermic on presentation and another 30% have poorly motile sperm that render their manufacturers functionally sterile. An increasingly common presentation of testis cancer is therefore via the infertility services. In urology outpatients, after examination, the patient should proceed to initial staging by routine haematology, biochemistry and measurement of AFP and HCG. A chest X-ray should be requested and an ultrasound examination of the testes ordered. The ultrasound will show features suggestive of testicular cancer, such as increased vascularity accompanying a mass. There may be additional features of microlithiasis, suggesting that the tumour has developed from carcinoma in situ. Carcinoma in situ is a bilateral condition with a 3% subsequent chance of development of a second testicular tumour. Rarely, patients with seminomas have very long histories of a testicular mass; the longest that the authors of this textbook have come across is 5 years and the patient with this history had stage 1 testis cancer. Following these investigations, arrangements should be made for the patient to proceed to orchiectomy. This is performed through a groin rather than a scrotal incision, which would lead to an increased risk of the scrotal spread of testicular cancer, particularly in cases where there are embryonal elements to the tumour. The testis is removed by the surgeon, cut in half, examined and sent for pathological examination. Following the histological confirmation of malignancy, CT imaging of the chest abdomen and pelvis should be organized (Figure 15.1) and serial tumour marker levels measured post-operatively (Figure 15.2). Tumour markers fall to normal levels in localized testis cancer, but will not do so in disseminated disease. The half-life of HCG is around 48 hours and of AFP is 5 days. There are four main types of testicular tumour: seminoma, teratoma, lymphoma and small cell (Figure 15.2). Teratoma constitutes approximately 75% of all testicular malignancies and appears cystic when examined by the naked eye. Pure seminoma constitutes 20% of tumours and is uniform in appearance. Approximately 5% of all testicular tumours are lymphoma, the appearance of which is generally uniform but with some areas of necrosis. Less than 1% of tumours are of small cell origin. These tumours have no specific macroscopic features. Microscopically, teratomas constitute a variety of different elements which may include cartilage, muscle, bone and virtually any other tissue. Subtypes of teratoma are described, and they are called undifferentiated, differentiated or choriocarcinoma (Figure 15.2). Seminoma consists of uniform and large cells with darkly standing nuclei. Figure 15.1 Testicular cancer. A 24-year-old Australian barman presented with a swollen testicle. (a) His ultrasound examination showed an enlarged left testicle with multiple low echogenicity areas and a small hydrocoele. (b) His body CT scan showed an enlarged and necrotic left para-aortic lymph node and (c) a right lower lobe peripheral lung nodule. His tumour markers were raised (serum AFP = 670 ng/mL; serum HCG = 56 IU/mL). Despite having metastatic disease at presentation, his chances of cure are over 90%. Figure 15.2 A classification of germ cell tumours and their tumour marker production. Having made a histological diagnosis, treatment is initiated and depends upon the stage to which the tumour has advanced. The following stages are described and determined by CT imaging of the chest, abdomen and pelvis: The disease is further sub-staged according to the size of the metastatic deposits and the number of pulmonary metastases. In the United States, retroperitoneal lymph node dissection is undertaken to stage testicular cancer, although this practice is disappearing. In our view, node dissection is not indicated as a routine staging procedure because of the major morbidity of the operation and also because of the side effects, which include retrograde ejaculation. Node dissection for staging purposes is not part of medical practice in the United Kingdom, which relies on imaging. Retrograde ejaculation is the ejaculation of sperm backwards into the bladder rather than forwards into the urethra. This phenomenon does not necessarily mean that the patient is functionally sterile, because sperm can be collected and artificial insemination techniques employed to successfully fertilize the patient’s partner. In modern times, such in vitro fertilization (IVF) programmes require aspiration of sperm from the testes or testicular biopsy with sperm retrieval if collection of urine post-ejaculation with sperm retrieval is unsuccessful. The tumour stage of testicular cancer defines its treatment. If the tumour is localized to the testis, two actions are available to the clinician. The first option for both seminoma and teratoma is observation without further therapy. If this policy is followed in the absence of poor prognosis pathology features, then the likelihood of any further treatment being required is 13% for testicular teratoma and 17% for seminoma. It should be noted that almost all patients who develop progressive disease during the period of observation without treatment are salvageable by chemotherapy. Active surveillance for stage I seminoma and stage I teratoma without lymphovascular invasion or embryonal elements is safe but requires regular follow-up with clinical examination, blood tests and radiology. In the United Kingdom, many urologists refer patients with stage I seminoma for radiotherapy, following which the prognosis is excellent, with virtually no chance of relapse. The option of single-agent carboplatin is a vastly better alternative. A randomized trial has shown that chemotherapy with carboplatin is as effective as radiation therapy and without the morbidity, two infusions being given at4-weekly intervals in contrast to 3 weeks of daily radiation therapy. Patients with stage I teratoma with high risk features are generally referred for adjuvant chemotherapy using bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) chemotherapy. Treatment in certain circumstances might be modified, dropping bleomycin from the treatment programme to reduce the risk of lung damage. For stage IIa seminoma, that is, with a nodal mass of less than 2 cm in diameter as defined by CT scanning, many clinicians in the United Kingdom advise treatment with radiotherapy. A consensus of opinion is now emerging, which follows the view that two courses of cytotoxic chemotherapy are equally as effective as radiation treatment in the control of this stage of disease. For stage IIb seminoma, that is, for patients with a disease mass of less than 5 cm, some clinicians, particularly radiotherapists, still treat with radiotherapy, but this is not generally advised in view of the side effects of large field radiotherapy. Chemotherapy should be given using cisplatin based combination chemotherapy. For all patients with greater than stage IIb disease, whether it is seminoma or teratoma, cytotoxic chemotherapy is given. Before the advent of cytotoxic chemotherapy for teratoma, the disease was invariably fatal. The development of effective chemotherapy programmes has bought about a revolution in the management of patients with malignancy, and now virtually all patients are cured by treatment. Treatment with cytotoxic agents was originally introduced into medical practice by Li in the early 1960s. As a result, approximately 8% of patients with advanced disease were cured, using a combination of agents that included actinomycin and chlorambucil. In the early 1970s, Samuels treated patients with vinblastine and bleomycin and produced remissions in approximately 50% of men treated. This treatment was of considerable toxicity because of the large dosages of vinblastine and bleomycin used and the relative lack of support programmes for patients with neutropenic sepsis and thrombocytopenia, which occur as a result of the use of these agents. In 1976, Einhorn introduced the bleomycin, vinblastine and cisplatinum (BVP) programme for the treatment of malignant testicular tumours. The introduction of BVP was not in the context of a controlled clinical trial but in a speculative fashion and was found to work. Because BVP turned out to be such an effective regimen, it became widely used even before the results were published. This regimen was enormously successful, and 70% of patients with advanced disease were cured. By substituting etoposide for vinblastine, less toxicity resulted with equivalent effect. Over the last decade, there have been further refinements in the way that treatment has been given. Drug treatment that initially required six courses of 5-day treatments has now been reduced to four courses of 3-day treatments. The expectation is that 95% of patients with good-prognosis tumour are cured with this regimen and 48% of patients with poor-prognosis disease are cured. Extraordinarily, there has been further change in the collective view with regard to chemotherapy for testicular cancer, and recently many oncologists have reverted to the original 5-day BEP programme. This is based upon analyses of huge numbers of patients and the realization of the superiority of this standard programme. At the end of treatment, one problem may be that of a persistent mass. By this we mean a residual tumour at the site of the original metastatic disease. The approach to this problem is to proceed to surgery. Surgery may be very extensive and involve both thoracotomy and laparotomy. At surgery, the residual mass of tumour is excised as completely as possible, and this may require dacron grafting of major vessels or removal of a kidney in order to take away the tumour completely. This operative procedure is extremely intricate. Histological examination of the excised mass shows that in one-third of cases there is necrotic tumour, in one-third of cases there is differentiated teratoma and in one-third of cases there is undifferentiated cancer. If necrotic tumour is found, no further action is taken. If undifferentiated tumour is found, further chemotherapy is given and 30–40% of patients will be cured by a combination of chemotherapy and surgery. In those patients who have residual differentiated tumour, it is important to remove the residual mass of the disease because over a 5-year period approximately 50% of differentiated tumours undergo further malignant change, transforming to undifferentiated malignancy. Unfortunately, a significant number of patients still have progressive or unresponsive tumours and for these patients there is still a possibility of cure, which is in the range of 20–40%. Treatment programmessuch as vinblastine, ifosfamide and cisplatin (VIP), paclitaxel, ifosfamide, cisplatin (TIP) or high-dose therapy with stem cell rescue are used to treat such patients. The effects of treatment are very closely monitored by measuring changes in the serum levels of the tumour markers AFP and HCG. These are hormones secreted by teratoma and seminoma. If the tumour is being treated effectively, then the levels of these hormones in the blood will decay over a known period: a half-life of 3–5 days for AFP and approximately 12–36 hours for HCG. There are specific toxicities that relate to treatment. Cisplatin will cause renal damage, deafness and peripheral neuropathy, which may manifest as numbness in the fingers or toes or complete loss of motor and sensory function in the limbs. Bleomycin unfortunately causes pulmonary toxicity, that is, an irreversible and progressive loss of lung function, which is fatal in approximately 2% of patients treated (see Figure 3.13). Bleomycin was omitted from Lance Armstrong’s treatment for metastatic testicular cancer so that he would not lose lung function and of course he went on to win seven consecutive Tour de France titles, albeit with the assistance of doping. Testicular cancer and the drug regimen that is used generally causes sterility; by this we mean loss of functional spermatogenesis. In 80% of patients, however, there is recovery of spermatogenesis, which generally occurs at 18 months from the completion of treatment. The treatment of teratoma and seminoma is highly complex and requires patient management in centres of excellence, where the delivery of chemotherapy and the maintenance of patients during neutropenic and thrombocytopenic episodes can be successfully achieved. In the best centres, 95% of patients with good-prognosis tumours are cured, which is without doubt a significant advance in medical science, as young men with this malignant tumour can be returned to an active life within the community after treatment. Prognostic indices have been described in detail by many authors; one of the more commonly used is described by the International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group. Patients with non-seminoma are classified as having good-prognosis disease with a 5-year survival of 92–95%, intermediate-prognosis tumours with a 72–80% 5-year survival and poor-prognosis tumours with a 48% 5-year survival. Patients with pure seminoma are described as having either good- or intermediate-prognosis disease. The classification into these categories is based on the presence or absence of non-nodal visceral metastases and serum levels of tumour markers. The influence of delay in diagnosis on prognosis is variably reported. Some authors link delay in excess of 1 year to a good prognosis, although this is described as being associated with a poor prognosis by other authors. Case Study: A tired suit.

Testis cancer

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Percentage of all cancer registrations

Rank of registrations

Lifetime risk of cancer

Change in ASR (2000–2010)

5-year overall survival

Male

Male

Male

Male

Male

Testis cancer

1

16th

1 in 190

+4%

97%

Presentation

Staging and grading

Treatment

Treatment of stage I testicular cancer

Treatment of stage II testicular cancer

Treatment of advanced testicular cancer

Treatment of residual tumour masses

Monitoring treatment

Side effects of treatment

Prognosis

ONLINE RESOURCE

ONLINE RESOURCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree