PERIPHERAL (MATURE) T-CELL LYMPHOMAS

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) is a heterogeneous group of lymphomas derived from a mature T cell (Fig. 9-1). Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) classification combines mature T- and natural killer (NK)-cell neoplasms under the umbrella term PTCL, and the category is composed of 23 different entities (Table 9-1), based on the different morphologic, phenotypic, molecular, and clinical features, including disease site (1). Most PTCLs lack distinct genetic or biologic alterations that are seen in B-cell lymphomas, such as t(14;18) in follicular lymphoma and t(11;14) in mantle cell lymphoma. Compared with B-cell lymphomas, many types of PTCL develop not in lymph nodes, but in specific extranodal sites such as extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKL) in the nasal cavity, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) in the small intestine, and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTL) in the liver and spleen.

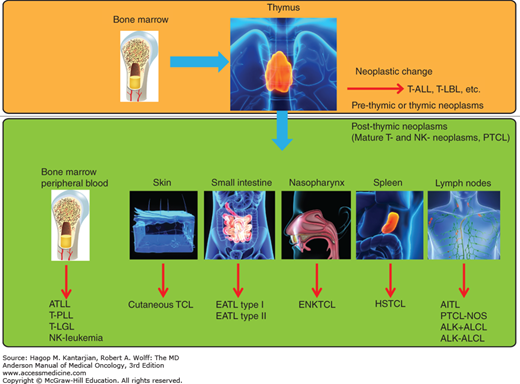

FIGURE 9-1

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma: T-cell maturation and organ of involvement. AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; ALCL, anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma; ATLL, adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia; EATL, enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma; ENKTCL, extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma; HSTCL, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma; NK, natural killer; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; PTCL-NOS, PTCL, not otherwise specified; T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; TCL, T-cell lymphoma; T-LBL, T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma; T-LGL, T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia; T-PLL, T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia.

Mature T-cell and NK-cell neoplasms |

T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia |

T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia |

Chronic lymphoproliferative disorder of NK cells |

Aggressive NK-cell lymphoma |

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type |

Systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childfood |

Hydroa vacciniforme-like lymphoma |

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma |

Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma |

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma |

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma |

Mycosis fungoides |

Sézary syndrome |

Primary cutaneous CD30-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders |

Lymphomatoid papulosis |

Primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma |

Primary cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma |

Primary cutaneous CD8-positive aggressive epidermotropic cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma |

Primary cutaneous CD4-positive small/medium T-cell lymphoma |

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified |

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma |

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK positive |

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, ALK negative |

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma represents 5% to 10% of all lymphomas in the United States (2). The most common histologic subtype is PTCL, not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS), followed by angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) or anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL), either ALK positive or ALK negative. The three types account for about 60% of all cases of PTCLs (3). The age-adjusted incidence in the United States for PTCL-NOS, AITL, and ALCL is 0.30, 0.05, and 0.25 per 100,000 person-years, respectively (2). Previous studies have indicated that some Asian countries have a higher incidence of PTCL (3). However, age-adjusted incidence estimated by population-based cancer registry data showed a similar incidence of PTCL in the United States and Japan except for NK/T-cell lymphoma (NKTCL) and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) (4). The incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) is higher in the United States, particularly in African Americans.

PRESENTATION AND HISTOPATHOLOGIC FINDINGS

The presentation of patients with T-cell lymphoma largely depends on the subtype. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified, AITL, and ALCL often present with generalized lymphadenopathy, and there is also frequent involvement of the skin, gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, and bone marrow. In contrast, a number of rare specific subtypes, such as NKTCL, HSTL, and EATL, present primarily with extranodal disease, and other subtypes, such as NKTCL and ATLL, may have a leukemic presentation. Advanced-stage disease (stages III and IV) is common: PTCL-NOS, 69%; AITL, 89%; ALK-positive ALCL, 65%; ALK-negative ALCL, 58%; EATL, 69%; and HSTL, 90%.

The histopathologic and immunophenotypic findings may vary within a given subtype. Therefore, the diagnosis should be made based on a combination of clinical presentation and histopathologic findings. T-cell receptor rearrangements are found in most cases of PTCL, but a negative result does not necessarily exclude the disease.

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified, represents the largest subtype and accounts for 25% to 30% of all PTCLs (1,3). Its definition in the current WHO classification is a “mature T-cell lymphoma which does not correspond to any of the specifically defined entities.” The diagnosis of PTCL-NOS should be made only when other specific entities have been excluded, and, therefore, it is a heterogeneous category at the genetic level.

There is male predominance (male-to-female ratio of approximately 2:1). Patients most often present with lymph node enlargement and with advanced-stage disease (60%-70%) with B symptoms. Extranodal presentation is also common (30%-40%), with the bone marrow, skin, and gastrointestinal tract being the most commonly affected sites (5,6).

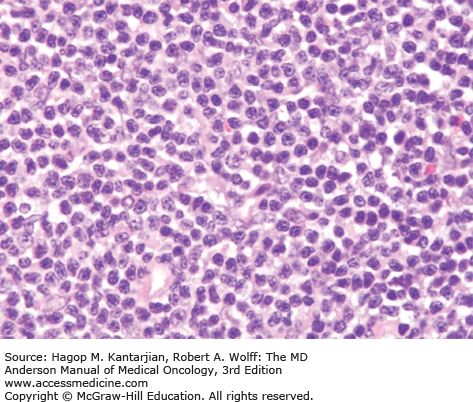

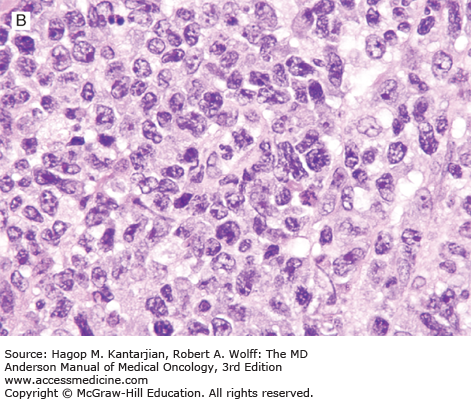

Histologically, the lymph node architecture is diffusely effaced (1). The cytologic spectrum is extremely broad ranging from highly polymorphous to monomorphous presentations. Most cases exhibit a spectrum of cell sizes from medium to large and can have abundant clear cytoplasm with irregular, pleomorphic, and hyperchromatic nuclei and high mitotic figures (Figs. 9-2 and 9-3). Reed-Sternberg–like cells may also be found.

Immunophenotypic studies show aberrant T-cell phenotype, typically marked by downregulation of CD5 and CD7. Nodal cases most often show CD4+/CD8– phenotype. T-cell receptor (TCR) β-chain (βF1) is usually expressed, allowing the distinction from γδ T-cell lymphomas and NK-cell lymphomas. Cytotoxic molecules, such as TIA-1 and granzyme B, are expressed in 40% of nodal PTCL-NOS, and expression is associated with younger age at presentation, aggressive features, treatment resistance, and inferior survival (7). CD30 expression is observed in 3% to 50% of cases (5,8,9). Lymphoma cells may occasionally express CD15, but the phenotypic profile and morphology allow the distinction from ALCL and Hodgkin lymphoma (9). Cytogenetic abnormalities in PTCLs are common, and karyotypes are often complex. Recurrent chromosomal gains have been observed in chromosomes 7q, 8q, 17q, and 22q, and recurrent losses in chromosomes 4q, 5q, 6q, 9p, 10q, 12q, and 13q, with del 5q, 10q, and 12q being associated with better outcome (10,11).

Gene expression profiling analysis has confirmed the molecular heterogeneity of the PTCL-NOS category. Using expression signatures, about one-third of PTCL-NOS cases can be classified as other known T-cell entities, such as AITL. In addition, cases of PTCL-NOS that remain can be divided into two groups characterized by high expression of GATA3 or TBX21, with the GATA3 group having poor survival (12).

These tumors are currently considered a variant of PTCL-NOS, but they have a distinctive follicular pattern and are thought to be derived for follicular T-helper cells, a small T-cell population that is CD10+, BCL6+, and PD-1/CD279+ in normal follicles. A recurrent t(5;9)(q33;q22), resulting in the ITK-SYK fusion gene, has been described in a subset of patients with follicular histology (13).

In the current WHO classification, two types of systemic ALCL are recognized. One type associated with translocations involving the ALK gene and leading to ALK overexpression is well established. The other category, morphologically similar to ALK-positive ALCL but lacking ALK abnormalities of overexpression, is considered a provisional category and designated as ALK-negative ALCL. However, there are recent data that show that the ALK-negative ALCL category is highly heterogeneous at the genetic level and that genetic abnormalities correlate with prognosis, calling into question the validity of the ALK-negative ALCL category.

Patients with ALK-positive ALCL are younger, with a median age in the low 30s, and children are commonly affected (14,15). Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma accounts for 3% to 5% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) and for 10% to 20% of childhood lymphomas (1). Patients with ALK-positive ALCL generally present with lymph node enlargement and frequent extranodal involvement of skin, bone, soft tissue, lung, and liver. More than half present with B symptoms at diagnosis, particularly fever.

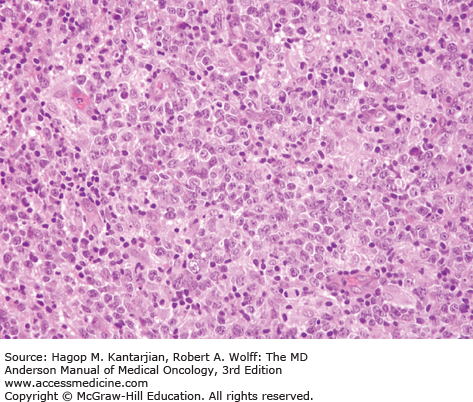

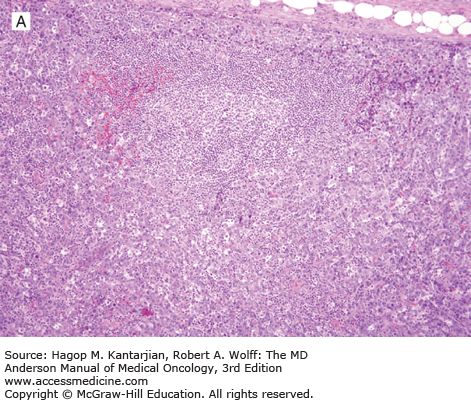

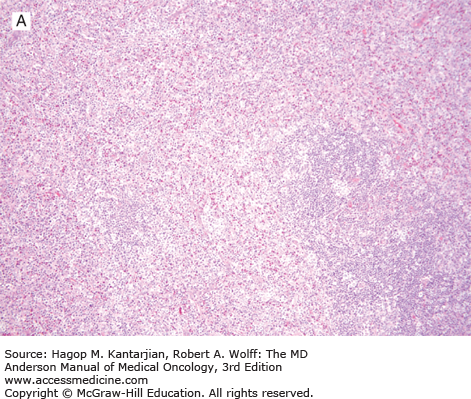

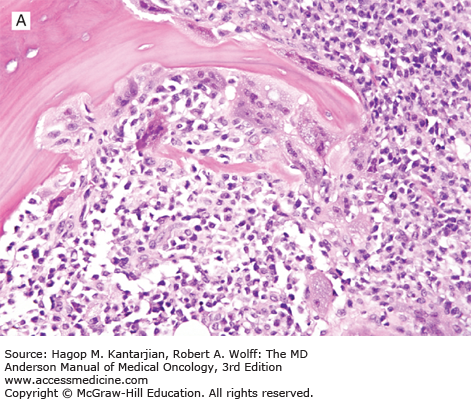

Histologically, ALK-positive ALCL exhibits a wide histologic spectrum (Fig. 9-4). A number of morphologic patterns have been recognized: common type, lymphohistiocytic, small cell, Hodgkin-like, sarcoma-like, and others, as well as mixed or composite patterns. About 80% of cases exhibit the common pattern, characterized by large lymphoma cells infiltrating sinuses and/or showing cohesive features. The lymphohistiocytic and small-cell patterns each represent 5% to 10% of cases of ALK-positive ALCL. In all variants, the lymphoma cells have eccentric, horseshoe- or kidney-shaped nuclei, often with an eosinophilic region near the nucleus (so-called hallmark cells). The cytoplasm is abundant and usually basophilic (see Fig. 9-4).

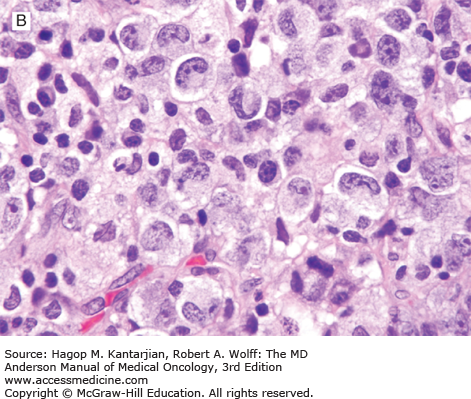

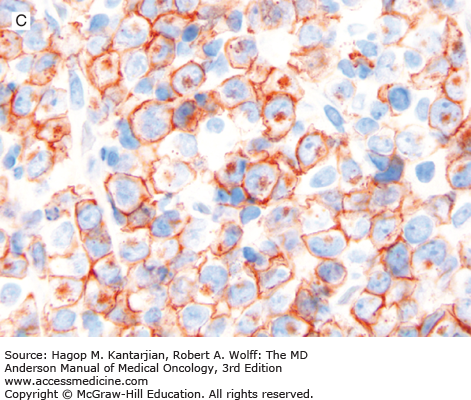

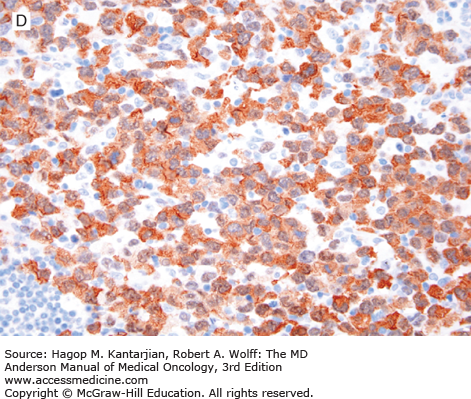

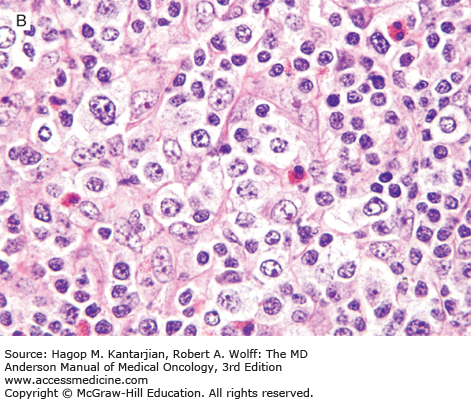

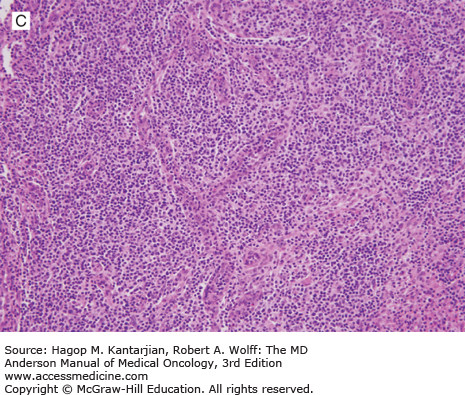

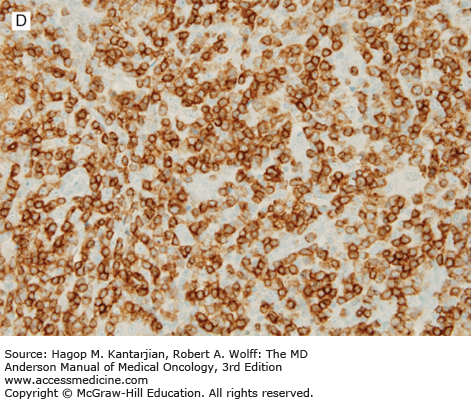

FIGURE 9-4

ALK-positive anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. A. In this field, the neoplasm is paracortical and spares a central lymphoid follicle. B. The neoplastic cells are large with horseshoe-shaped nuclei. C, D. The neoplastic cells express CD30 (C) and ALK (D). (A, B, hematoxylin-eosin; A, 100×; B, 1,000×; C, D, immunohistochemistry; C, 1,000×; D, 400×).

ALK-positive ALCL is a lymphoma of T/null-cell lineage that is characterized by strong and diffuse CD30 and ALK expression. Most of cases are CD2+, CD4+, CD43+, CD3–, CD8–, and BCL2–. CD15 and PAX5 are negative (unlike classical Hodgkin lymphoma). The pattern of ALK expression, in part, can predict molecular abnormalities involving ALK. Cytoplasmic and nuclear expression correlates with the t(2;5)(p23;q35)/NPM1/ALK (16). Other cases with ALK abnormalities show a cytoplasmic restricted or, rarely, a membranous pattern of expression (17).

Patients with ALK-negative ALCL are older, with a median age in the late 50s. Clinically patients present with aggressive disease, with lymph node enlargement, frequent extranodal involvement, and B symptoms. The morphologic spectrum of ALK-negative ALCL is similar to ALK-positive ALCL, except that the neoplastic cells may be more pleomorphic. The neoplastic cells have a T/null-cell immunophenotype and strongly and uniformly express CD30 but are negative for ALK.

A recent study has shown that ALK-negative ALCL is molecularly heterogeneous. Rearrangement of DUSP22, marked by t(6;7), was found in 30% of cases and is associated with excellent prognosis with 90% long-term survival, whereas TP63 rearrangement, marked by inv(3), was seen in 8% of cases and is associated with poor prognosis with only 17% long-term survival. The remaining cases are still poorly characterized.

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma was first described as angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia in 1974 and was thought to be a preneoplastic process. Evidence now indicates that AITL is a de novo PTCL. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma represents the second most common subtype, accounting for 15% to 20% of PTCLs (3).

The median age of patients with AITL is 65 years (18,19). Most patients present with advanced disease. Generalized lymphadenopathy and extranodal presentations, including hepatosplenomegaly, bone marrow involvement, rash with pruritus, ascites, and pleural effusion are frequent. B symptoms (fever, night sweats, weight loss) are common. Laboratory abnormalities include polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia (sometimes with a positive direct Coombs test), anemia, hypereosinophilia, thrombocytopenia, and positive autoantibodies for cold agglutinin, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear factor, and anti–smooth muscle antibody are also common (18,19).

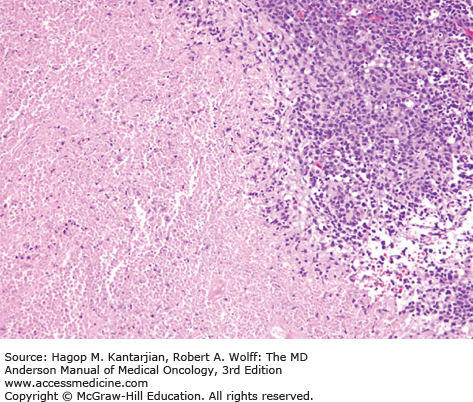

Histologically, the lymph node architecture is replaced by a diffuse, polymorphous population of cells associated with a proliferation of branching high endothelial venules. The neoplastic cells are small to medium in size, often with abundant clear cytoplasm, and can form small clusters surrounding the follicles and high endothelial venules (Fig. 9-5). Reactive cells are numerous in AITL, such as lymphocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells, histiocytes, and CD21+ follicular dendritic cell networks. Most cases also show expansion of B cells positive for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which is thought to be related to immune dysfunction.

FIGURE 9-5

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. A. The neoplasm has a paracortical distribution. B. The neoplasm is composed of numerous cells with clear cytoplasm. C. In this field, arborizing blood vessels are shown. D. The neoplastic cells are positive for CD3. (A-C, hematoxylin-eosin; A, 100×; B, 1,000×; C, 200×; D, immunohistochemistry, 400×).

In AITL, lymphoma cells usually express T-cell antigens such as CD3, CD2, and CD5, and have a T-helper cell immunophenotype characterized by expression of CD4, CD10, BCL6, CXCL13, and PD-1. Follicular dendritic cells (CD21+, CD23+) are expanded, usually surrounding high endothelial venules.

Chromosomal abnormalities have been identified in AITL, with trisomy 3 and trisomy 5 being most common (20). Recent studies have shown mutations in TET2, IDH2, DNMT3A, and RHOA (21). Among 243 patients in the International T-Cell Lymphoma Project, 5-year failure-free survival and overall survival (OS) rates were 18% and 32%, respectively, which was very similar to the outcome of patients with PTCL-NOS (18).

Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia is a distinct clinicopathologic entity associated with infection by the human T-cell lymphotropic virus type-1 (HTLV-1) (1). The HTLV-1 is a single-stranded RNA retrovirus that is lymphotropic for T lymphocytes. Infection with HTLV-1 is endemic in Africa, Iran, the Caribbean islands, Central and South America, and the southern part of Japan (22). Approximately 10 to 20 million people are infected by HTLV-1 worldwide. Three major routes of HTLV-1 infection have been established: vertical transmission by breastfeeding, parental transmission, and sexual transmission. The lifetime cumulative incidence of ATLL in an HTLV-1 carrier is 2% to 3% for women and 6% to 7% for men (23). The median age at the time ATLL develops is the seventh decade of life. Risk factors for developing ATLL include high proviral load, advanced age, family history of ATLL, and types of human leukocyte antigen alleles (24). Individuals infected in adulthood rarely, if ever, develop ATLL, suggesting that the latency of infection is very long and age at the time of HTLV-1 infection is important (25). Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia accounts for less than 1% of NHL in the United States but accounts for around 35% to 40% of NHL in the endemic area in Japan (4). However, there seems to be an increasing trend in the incidence of ATLL in the United States, possibly due to the emigration of people from endemic areas (26). The prognosis is extremely poor with conventional chemotherapy (27). Median OS is less than 1 year without allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia is classified into four subtypes based on clinicopathologic features and prognosis: acute, lymphoma, chronic, and smoldering (28). Patients with acute ATLL, the most common form of the disease, have generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, skin lesions, peripheral blood involvement, lytic bone lesions, and hypercalcemia. Hypercalcemia may also develop in the absence of bone lesions, secondary to secretion of parathyroid hormone–related peptide by the neoplastic cells (Fig. 9-6).

In the peripheral blood, the neoplastic cells are medium-sized, with basophilic cytoplasm and markedly irregular, multilobulated nuclei, including cloverleaf shapes (also known as flower cells) (1). The neoplastic cells in lymph nodes and viscera exhibit a spectrum of cell sizes, including small, medium, and large, with relatively round or markedly irregular nuclear contours. Histopathologic findings are not specific for ATLL, and testing for HTLV-1 antibody is needed for suspicious cases even in non-endemic areas.

Immunophenotypic studies show a mature T-cell immunophenotype. The neoplastic cells intensely express CD25 antigen. They also frequently express the chemokine receptor CCR4 and FOXP3, suggesting that regulatory T cells are the closest normal counterpart (29).

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma is an aggressive lymphoma that can have an NK-cell or cytotoxic T-cell immunophenotype and may arise from a precursor cell of NK/T cells. It occurs predominantly in the nasal/paranasal area and much less often at nonnasal sites, such as skin/soft tissue and the gastrointestinal tract (1). Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma is more prevalent in Asians and Native Americans in Central and South America (4). Its pathogenesis is unknown; however, the lymphoma cells in essentially all cases are positive for EBV-encoded RNA (EBER), suggesting a very strong association between EBV infection and oncogenesis. Patients with nasal involvement present with symptoms of nasal congestion or epistaxis. With locally advanced disease, the tumor erodes the palate and bone, causing pain, fistula, and infection. Some cases may be complicated by hemophagocytic syndrome (30).

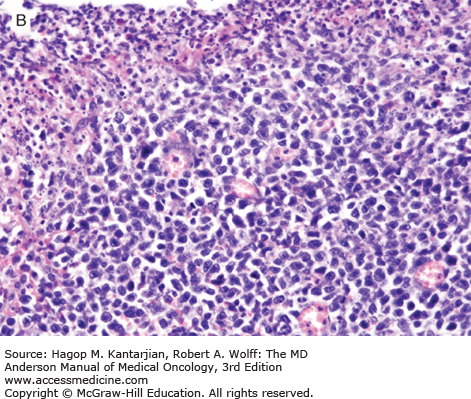

Histologically, ENKL shows a diffuse proliferation of lymphoma cells, often with an angiocentric or angiodestructive growth pattern, associated with a mixture of reactive lymphocytes and histiocytes. Fibrinoid change can be seen in the blood vessels. Granulocytes are rare unless associated with necrotic changes (Fig. 9-7).

Typically, the lymphoma cells express the NK-cell marker CD56, CD2, and cytoplasmic CD3 and are negative for surface CD3, CD5, and TCR. Cytotoxic molecules such as TIA-1, granzyme B, and perforin are also positive. Deletion of chromosome 6 is the most frequent cytogenetic aberration (31). Chromosome 6 includes two genes named PRDM1 and FOXO3, which may play a role in lymphomagenesis (32). Outcome with conventional chemotherapy is poor, with a median OS of 1 to 2 years (33). High EBV DNA load in plasma is associated with lower response rate to chemotherapy and worse outcome (34).

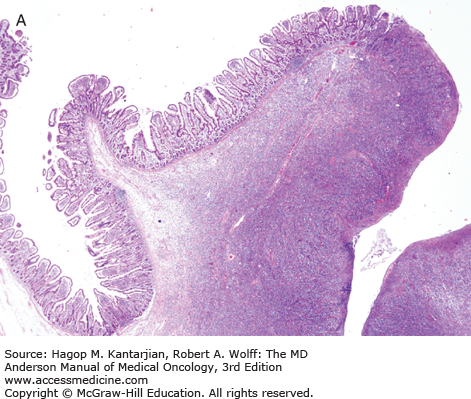

Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma is a rare primary intestinal lymphoma often localized (but diffusely infiltrating) in the small intestine (1). Two types of EATL are recognized. Type I accounts for 80% to 90% of EATL, shows large lymphoid cells with an inflammatory background, and is strongly associated with celiac disease. Type II EATL accounts for 10% to 20% of EATL, shows monomorphic medium-sized lymphoma cells, and occurs sporadically, often without a history of celiac disease. Type I is predominant in Europe whereas type II is more common in Asia (35). Patients present frequently with abdominal pain, weight loss, and sometimes intestinal perforation (36).

Grossly, the involved intestine demonstrates multiple ulcers (Fig. 9-8), which may extend deeply into the bowel wall, often resulting in perforation; a distinct mass may not be found. The jejunum is the most common site of involvement. Histologically, the neoplasms are diffuse, and the neoplastic cells are a mixture of small, medium, and large lymphoid cells (see Fig. 9-8).

The intestine not involved by neoplasm may exhibit blunting of villi, as is seen in celiac disease.

Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma expresses pan-T-cell antigens and usually has a cytotoxic profile positive for TIA-1, granzyme B, and perforin. Type II EATL expresses CD56 more often than type I EATL (35). Comparative genomic hybridization analysis often shows amplification of chromosome 9p31.3-qter and deletions of chromosome 16q12.1. The prognosis is poor, with a median OS of 10 months (35).

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma accounts for less than 1% of all NHL and is derived from cytotoxic T cells. Most cases express the gamma-delta (γδ) TCR, but a minority of cases express the alpha-beta (αβ) TCR (1). Lymphoma cells predominantly involve the spleen, liver, and bone marrow. Peak incidence is in adolescents and young adults with a median age of 35 years. There is strong male predominance (1,37).

Patients typically present with hepatosplenomegaly (abdominal pain) and B symptoms. Because of the hepatosplenomegaly and bone marrow involvement, patients often manifest marked cytopenia, most prominently thrombocytopenia. Chronic immune suppression seems to be associated with the risk of HSTL; up to 20% of patients develop the disease after solid organ transplantation or chronic antigenic stimulation.

Histologically, these neoplasms are composed of medium-sized lymphoid cells with slightly irregular nuclear contours, condensed chromatin, and small nucleoli (1). In the liver, HSTL infiltrates sinusoids and spares portal tracts. In the spleen, the red pulp is involved and the white pulp spared (Fig. 9-9). In the bone marrow, the neoplastic cells can resemble blasts in aspirate smears and are commonly intrasinusoidal in core biopsy specimens.

FIGURE 9-9

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma involving spleen (hematoxylin-eosin, 400×).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree