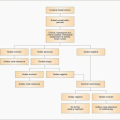

Treatment strategies

The majority of patients with localized breast cancer receive some form of systemic therapy. The intention of these systemic treatments (adjuvant therapy) is to kill or prevent growth of cancer cells which have escaped from the local area but have not yet grown to a size to cause local symptoms or be detectable on imaging. Systemic treatment can be given prior to local treatment (neoadjuvant therapy) which can also cause shrinkage of the primary tumour. This allows confirmation that the medication used is active against the cancer and may allow breast conservation for a lesion that would have been too large at diagnosis to allow this. The order in which systemic treatment is given does not appear to affect long-term survival. Three forms of systemic treatment are used: (1) hormonal therapy, (2) cytotoxic chemotherapy, and (3) immunotherapy directed against a specific tumour antigen.

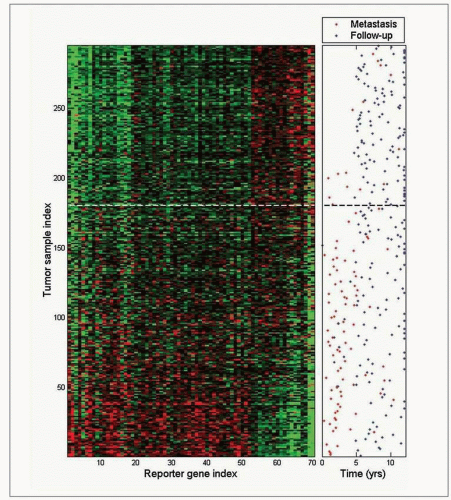

It is not possible to predict precisely those who will develop recurrent or metastatic cancer and would therefore potentially benefit from adjuvant treatment and those who will not develop further disease who will thus not need treatment. An estimation of the risk of further problems can be gained using established prognostic factors. Factors known to be associated with increased risk of recurrence can be weighed together with issues such as general health to provide an estimate of the risk of recurrence and allow identification of those who have the most to gain by treatment.

It is important to recognize, however, that prognostication is an inexact science. Some patients deemed to be at low risk will develop recurrence, others at high risk who do receive treatment would not have gone on to have problems without treatment, and some at high risk who receive treatment will still die from metastatic disease. Importantly, these factors do not tell us who will gain benefit from treatment because they are markers of increased risk not markers of benefit. These factors are used to try to balance known risks and side-effects that an individual will suffer against the potential benefit in terms of absolute chance of improvement or survival.

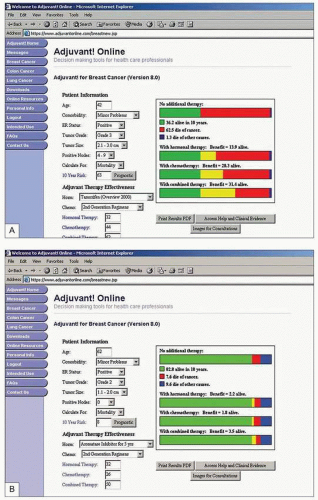

Such risks and benefits inform the detailed discussions, initially within the multidisciplinary team and subsequently with each patient, to help arrive at the most appropriate treatment option for that individual. Tumour size, histological grade, receptor status, and axillary lymph node involvement together with patient age, menopausal status, and fitness are the main factors used to determine decisions on systemic therapy. Various tools exist to combine these factors and divide patients into groups according to risk including the Nottingham Prognostic Index (

Table 10.1), St Gallen Consensus, and online tools such as Adjuvantonline. Analysis of genetic characteristics of individual cancers offers the prospect of more rational and tailored therapy and is beginning to be used to determine risk and guide treatment.

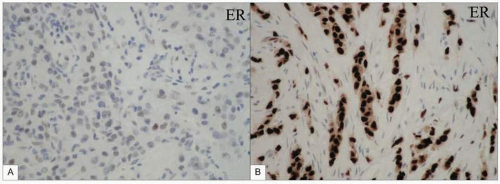

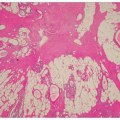

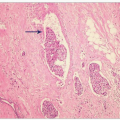

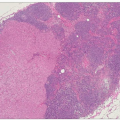

Approximately 75% of breast cancers bear receptors on their cells for oestrogen. The majority are oestrogen alpha receptors, which stimulate cell growth, although the proportion of cells bearing receptors and number of receptors per cell may vary (this is assessed by the Allred score). Oestrogen beta receptors also exist as do receptors for progesterone although these provide little extra useful information to help direct treatment. The response of a breast cancer to oophorectomy reported by Beatson from Glasgow in 1896 demonstrated that a reduction in oestrogen stimulation of breast cancer can cause tumour regression. While surgical ovarian ablation is used infrequently, medical ovarian suppression using an

LHRH agonist is utilized in some premenopausal women in both the metastatic and adjuvant settings.

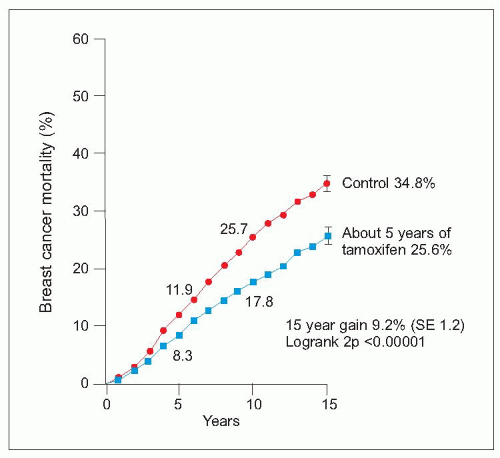

Tamoxifen is a selective oestrogen receptor modulator which has antagonistic actions in breast cancers bearing oestrogen receptors but agonist actions on endometrium, lipids, and bone. Tamoxifen reduces the risk of death from breast cancer by approximately 25% and is effective in all age groups regardless of menopausal status. A dose of 20 mg daily is usually given for 5 years. Tamoxifen reduces risk of contralateral breast cancer between 40 and 50% but appears less effective against human epidermal growth factor receptor (

HER)2-positive tumours. It is more effective given after chemotherapy (if this is also indicated) rather than concurrently. Side-effects include venous thromboembolism, hot flushes, gastrointestinal upset, vaginal discharge or dryness, altered libido, menstrual disturbance, and endometrial cancer.

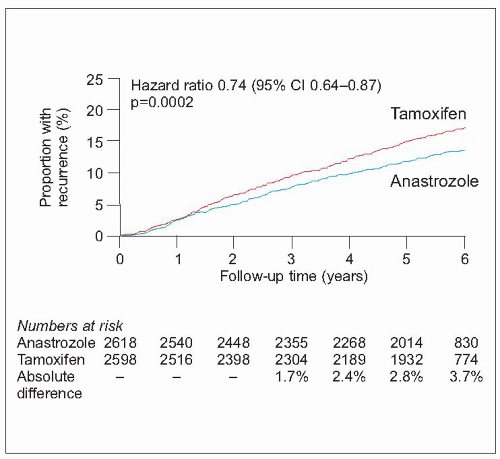

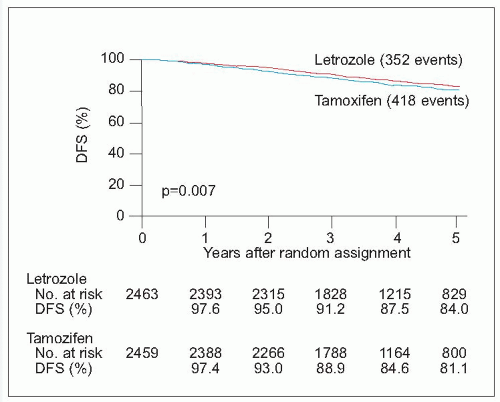

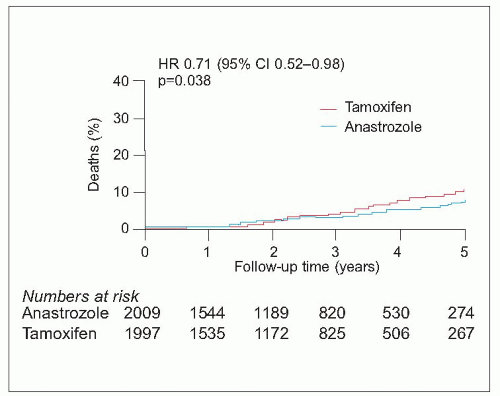

There has been a recent explosion of interest in the new generation of aromatase inhibitor drugs, which block conversion of androgens to oestrogens by the aromatase enzyme in postmenopausal women, markedly reducing circulating oestrogen concentrations. The currently available drugs include the nonsteroidal agents, anastrozole and letrozole, and the steroidal agent, exemestane. They are only effective in postmenopausal women with oestrogen receptor-positive tumours. Compared to tamoxifen, these drugs improve disease-free and metastasis-free survival in various settings but the situation is complicated by the fact that trials have used different drugs in different settings. They appear superior to adjuvant tamoxifen if given instead of tamoxifen (anastrozole and letrozole) or if patients are switched after 2-3 years of tamoxifen (anastrozole and exemestane) compared with continuing on tamoxifen. Letrozole also reduces the risk of recurrence when used as extended adjuvant therapy after 5 years on tamoxifen. They reduce the risk of contralateral breast cancer by a further 40-50% above that achieved by tamoxifen. They also appear to be equally effective in both

HER2-positive and negative cancers. Overall survival benefit has so far been

demonstrated when used after 2-3 years of tamoxifen (switching) or after 5 years of tamoxifen (extended adjuvant).

Side-effects include hot flushes (less than tamoxifen), joint pain, osteoporosis, fatigue, and vaginal dryness. Aromatase inhibitors are substantially more expensive than tamoxifen and many women require bone density monitoring during treatment because of the adverse effect of these agents on bone turnover. Recommendations are evolving constantly but it is suggested that very low-risk postmenopausal women are treated with 5 years of tamoxifen, those at moderate risk take 2-3 years of tamoxifen followed by 2-3 years of an aromatase inhibitor or 5 years of tamoxifen followed by 3 years of an aromatase inhibitor, and those at high risk should receive 5 years of an aromatase inhibitor following surgical treatment. Those currently completing 5 years of tamoxifen who are at moderate or high risk of continued recurrence are recommended to take at least 3 further years of an aromatase inhibitor.

Endocrine therapy can be used, particularly in postmenopausal women, as neoadjuvant treatment of large operable or locally advanced oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancers to reduce the size of cancers that are too large to allow breast conservation. The aromatase inhibitor letrozole achieves the best results in this setting and is the agent of choice.

In patients unfit or unwilling to undergo surgical treatment, endocrine therapy (letrozole in postmenopausal women) can be used either initially to permit surgery later or as sole treatment. Careful monitoring of such patients is required as tumours can escape from the control of endocrine agents even after months or years of response and then attention turns again to consideration of local therapy, often in less favourable circumstances.