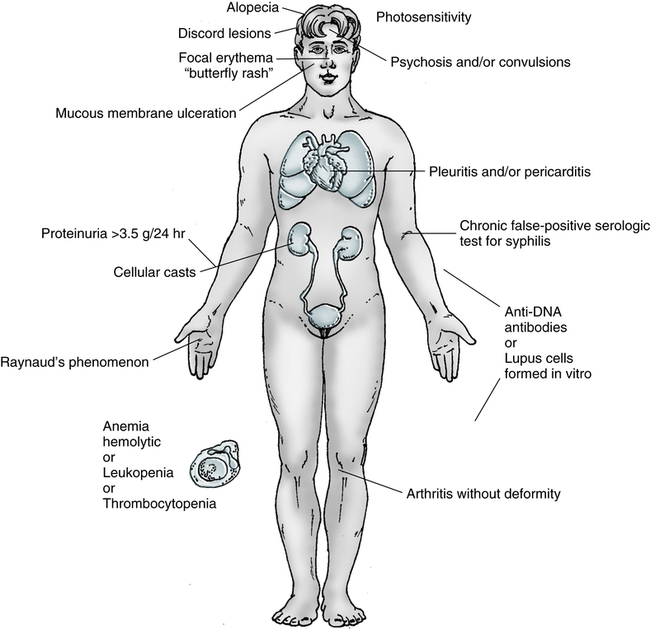

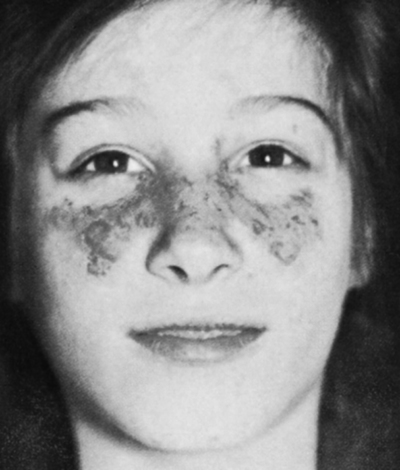

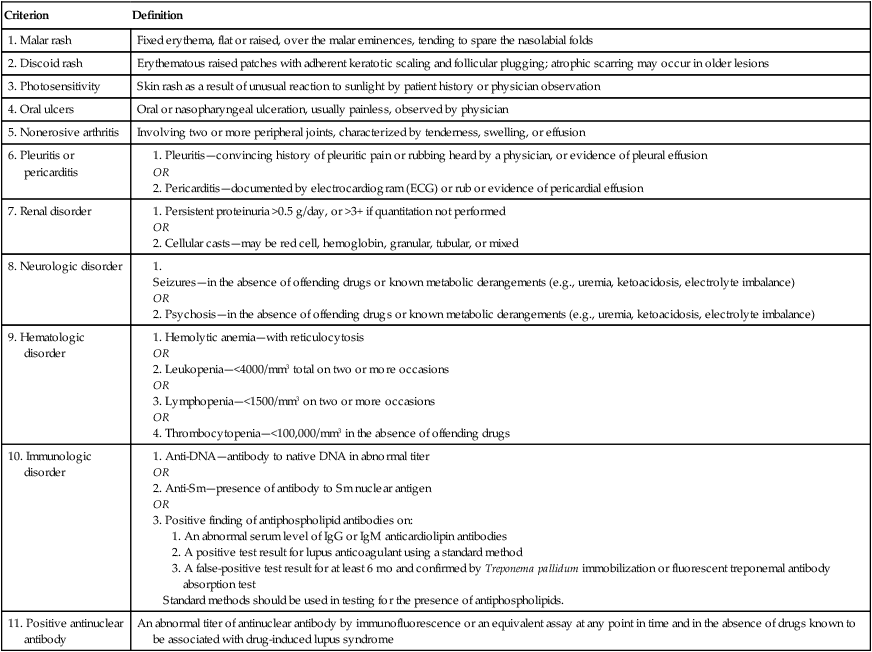

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader should be able to: • Compare the different forms of lupus, citing manifestations, incidence, and other features. • Name the two most common drugs that can cause drug-induced lupus. • Explain the epidemiology and signs and symptoms of SLE. • Describe the immunologic manifestations of SLE, including diagnostic evaluation. • Discuss the laboratory evaluation of antinuclear antibodies. • Analyze selected SLE case studies. Correctly answer case study related multiple choice questions • Be prepared to participate in a discussion of critical thinking questions. • Describe the principle, sources of error, limitation, and clinical application of the antinuclear antibody visible method • Describe the principle and clinical applications of the rapid slide test for antinucleoprotein and autoimmune enzyme immunoassay ANA screening test Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the classic model of an autoimmune disease. SLE is a systemic rheumatic disorder and the term used most often for the group of disorders that includes SLE and other abnormalities involving multiple systems (e.g., joints, connective tissue, collagen vascular system) in the disease process. Table 29-1 lists the American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification of SLE. Table 29-1 1. Anti-DNA—antibody to native DNA in abnormal titer 2. Anti-Sm—presence of antibody to Sm nuclear antigen 3. Positive finding of antiphospholipid antibodies on: 1. An abnormal serum level of IgG or IgM anticardiolipin antibodies 2. A positive test result for lupus anticoagulant using a standard method 3. A false-positive test result for at least 6 mo and confirmed by Treponema pallidum immobilization or fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test Standard methods should be used in testing for the presence of antiphospholipids. From Hochberg MC: Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus (letter), Arthritis Rheum 40:1725, 1997 and The American College of Rheumatology www.rheumatology.org 2012. There are several forms of lupus, including discoid, systemic, drug-induced, and neonatal lupus. Drug-induced lupus occurs after the use of certain prescribed drugs (Box 29-1). The most frequently used drugs associated with drug-induced lupus are hydralazine hydrochloride and procainamide hydrochloride. Factors such as the rate of drug metabolism, the drug’s influence on immune regulation, and the host’s genetic composition are all believed to influence pathogenesis. Some drugs (e.g., oral contraceptives, isoniazid) induce serum antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) without symptoms. High antibody titers may exist for months without the development of clinical symptoms. Manifestations of the disease range from a typical mild illness limited to a photosensitive facial rash and transient diffuse arthritis to life-threatening involvement of the CNS or renal, cardiac, or respiratory system (Fig. 29-1). In the early phases, it is often difficult to distinguish SLE from other systemic rheumatic disorders, such as progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS), polymyositis, primary Sjögren’s syndrome, primary Raynaud’s phenomenon, and rheumatoid arthritis. Polyarthritis and dermatitis are the most common clinical manifestations. The course of the disease is highly variable. It usually follows a chronic and irregular course, with periods of exacerbations and remissions. Clinical signs and symptoms can include fever, weight loss, malaise, arthralgia (joint pain) and arthritis (inflammation of the joints), and the characteristic erythematous, maculopapular (“butterfly”) rash over the bridge of the nose (Table 29-2). In addition, there is a tendency toward increased susceptibility to common and opportunistic infections. Multiple organ systems may be affected simultaneously. Table 29-2 Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Symptoms Adapted from Lupus Foundation of America: General Lupus Fact Sheet, 2012 (http://www.lupus.org/webmodules/webarticlesnet/?z=8&a=351org). Approximately 20% to 25% of patients with SLE develop dermal disorders as the initial manifestation of the disease. As many as 65% of patients will develop a cutaneous abnormality during the course of the disease. The characteristic erythematous, maculopapular butterfly rash across the nose and upper cheeks is the cutaneous feature for which the disease is named—lupus erythematosus, the “red wolf” (Fig. 29-2). This rash may also be observed on the arms and trunk. Exposure to UV light will worsen erythematous, as well as other types of, cutaneous lesions.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Criterion

Definition

1. Malar rash

Fixed erythema, flat or raised, over the malar eminences, tending to spare the nasolabial folds

2. Discoid rash

Erythematous raised patches with adherent keratotic scaling and follicular plugging; atrophic scarring may occur in older lesions

3. Photosensitivity

Skin rash as a result of unusual reaction to sunlight by patient history or physician observation

4. Oral ulcers

Oral or nasopharyngeal ulceration, usually painless, observed by physician

5. Nonerosive arthritis

Involving two or more peripheral joints, characterized by tenderness, swelling, or effusion

6. Pleuritis or pericarditis

7. Renal disorder

8. Neurologic disorder

9. Hematologic disorder

10. Immunologic disorder

11. Positive antinuclear antibody

An abnormal titer of antinuclear antibody by immunofluorescence or an equivalent assay at any point in time and in the absence of drugs known to be associated with drug-induced lupus syndrome

Different Forms of Lupus

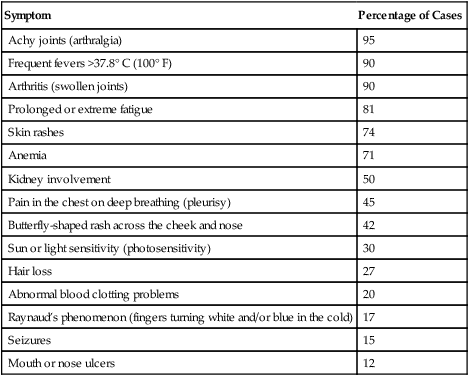

Signs and Symptoms

Symptom

Percentage of Cases

Achy joints (arthralgia)

95

Frequent fevers >37.8° C (100° F)

90

Arthritis (swollen joints)

90

Prolonged or extreme fatigue

81

Skin rashes

74

Anemia

71

Kidney involvement

50

Pain in the chest on deep breathing (pleurisy)

45

Butterfly-shaped rash across the cheek and nose

42

Sun or light sensitivity (photosensitivity)

30

Hair loss

27

Abnormal blood clotting problems

20

Raynaud’s phenomenon (fingers turning white and/or blue in the cold)

17

Seizures

15

Mouth or nose ulcers

12

Cutaneous Features

Oncohema Key

Fastest Oncology & Hematology Insight Engine