Syphilis

J. Dennis Fortenberry

KEY WORDS

Latent syphilis

Neurosyphilis

Nontreponemal tests

Primary syphilis

Reverse sequence syphilis screening

Secondary syphilis

Syphilis is an acute, localized sexually transmitted infection (STI) leading, if untreated, to systemic infection and chronic disease. Outbreaks among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) are common, often through connected social and sexual networks.1 Syphilis is sometimes asymptomatic but often is associated with localized signs of primary infection such as an ulcer at the infection site, or evidence of disseminated secondary infection manifested by symptoms such as skin rash, lymphadenopathy, fever, or mucocutaneous lesions.

Syphilis is caused by Treponema pallidum, a motile, spiral microorganism (spirochetes) 6 to 15 µm in length and about 0.20 µm in diameter.

Most infections are contracted by sexual contact, including kissing, penile-vaginal and penile-anal intercourse. Nonsexual transmission from direct contact with cutaneous or mucous membrane lesions is rare. Other transmission modes include maternal-fetal transplacental congenital infections, peripartum infection of newborns by contact with maternal genital lesions, and transfusion-related transmission. The estimated rate of transmission after sexual exposure to a person with primary or secondary syphilis is 30% or higher.

Syphilis in the US waxes and wanes in 7- to 10-year cycles. Rates of primary and secondary syphilis in the general population increased annually during 2001 to 2009, decreased in 2010, and increased between 2011 and 2013. In 2013, rates again increased (to 5.5 cases per 100,000 population), when 17,375 cases of primary and secondary syphilis were reported in the US. Of these, 900 (5.2%) were 15- to 19-year-olds and 3,642 (21%) were among 20- to 24-year-olds. In 2013, 23 cases of syphilis were reported among 10- to 14-year-olds.

Syphilis epidemiology demonstrates the extreme health disparities associated with many STIs.2

Geographic disparity: Syphilis has substantial geographic concentration, with more than 50% of primary and secondary cases reported from 1% of the US counties. The southeastern part of the US bears a heavy burden of syphilis, with more than 40% of national cases of primary and secondary syphilis reported from this region.

Racial disparity: Primary and secondary syphilis rates in 2013 were 16.8 per 100,000 among Black 15- to 19-year-olds, compared to 1.2 per 100,000 among White 15- to 19-year-olds. Comparable rates among 20- to 24-year-olds were 56.8 and 6.1 per 100,000 for Black and for White youth, respectively.

Gender disparity: Men-to-women ratios of primary and secondary syphilis were 3.5 among 15- to 19-year-olds in 2013, compared to 7.4 among 20- to 24-year-olds. Recent increases in rates were among men (rising from 8.1 to 9.2 to 10.3 cases per 100,000 in 2011, 2012, and 2013, respectively), compared to relatively stable rates among women (about 0.9 cases per 100,000).

Sex partner disparity: Men with men sex partners account for the majority of cases of primary and secondary syphilis in the US. Among heterosexual individuals, cases decreased during 2008 to 2011 (18.4% among women and 25.9% among men who have sex with women), but increased during 2011 to 2013 (2.9% among women and 14.4% among men who have sex with women). Among men who have sex with men, cases increased annually during 2007 to 2013 (75%).

T. pallidum produces an immediate localized inflammatory response, associated with regional lymphadenopathy. Antibody responses can be detected within a week of infection. A delayed hypersensitivity response clears most—but not all—organisms in local lesions within about 14 days.3 Inflammation and local tissue necrosis cause the characteristic induration and ulcer formation of primary syphilis. Dissemination via blood and lymphatics occurs within a few days of infection. Dysregulation of the delayed hypersensitivity response is associated with gumma formation characteristic of late syphilis.4

The clinical manifestations of syphilis depend on the time since infection and the specific body areas and organs infected. Five stages of syphilis are identified: primary, secondary, early latent, late latent, and late syphilis. Late syphilis (other than late congenital syphilis) is not seen in AYAs and is not additionally considered in this chapter. Neurosyphilis has various manifestations and occurs at any stage.5

Primary Syphilis

Syphilis should be considered for any ulcerating lesion of the genitals, cervix, anus, or lips/mouth, but lesions of fingers, arms, and breasts are more common than reported. Primary lesions appear after an incubation period of 9 to 90 days (average is 21 days). Characteristics of primary syphilis are:

Single lesions are 1 to 2 cm in size, but multiple lesions are common. Lesions may also appear as “kissing lesions,” adjacent ulcers across a fold of skin.

Ulcers are typically painless and described as having a punched out, clean appearance, with slightly elevated, firm margins. However, ulcer characteristics are an unreliable basis for the diagnosis of syphilis.6

Bilateral regional lymphadenopathy, with firm, nonsuppurative, usually nontender nodes.

Ulcers typically heal within 3 to 6 weeks.

Systemic symptoms such as fever, myalgia, or malaise are uncommon.

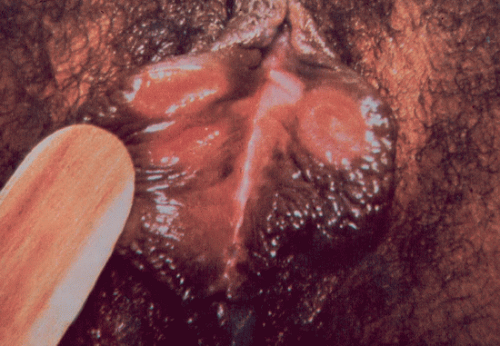

FIGURE 59.2 Primary syphilis: an ulcer on the left labium. (From Sweet RL, Gibbs RS. Atlas of infectious diseases of the female genital tract. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.) |

Secondary Syphilis

Secondary syphilis appears 6 to 8 weeks after infection and 4 to 10 weeks after the onset of the primary ulcer. T. pallidum can be identified in lesions and body fluids.7 Signs and symptoms:

Rash (about 90% of individuals with secondary syphilis).

Involves the trunk and extremities with predilection for palms and soles. Lesions on palms and soles may be scaly and hyperkeratotic (Fig. 59.4).

Rashes are bilateral and symmetrical, and tend to follow the lines of cleavage.

Sharply demarcated lesions, 0.5 to 2.0 cm in diameter, with a reddish-brown hue.

Rash is most commonly macular, papular, or papulosquamous, but almost any type of rash is reported, including acneform lesions, herpetiform lesions, and lesions similar to psoriasis. Lesions in intertriginous areas may erode and fissure, especially in the nasolabial folds and near the corners of the mouth. In warm, moist areas, hypertrophic granulomatous lesions (condylomata lata) may occur (Fig. 59.5).

Lesions are typically nonpruritic, but pruritus is sometimes reported.

Rash lasts a few weeks to 12 months but resolves quickly with treatment.

General or regional lymphadenopathy (approximately 70%)

Rubbery, nonpainful nodes, without suppuration

Occasional hepatosplenomegaly

Flu-like syndrome (approximately 50%)

Sore throat, fever, and malaise most common

Headaches

Lacrimation and nasal discharge

Arthralgia and myalgia

Alopecia (uncommon): Moth-eaten—appearing alopecia of the scalp and eyebrows

Other rare manifestations

Arthritis or bursitis

Hepatitis

Iritis and anterior uveitis

Glomerulonephritis

Latent Syphilis

Latent syphilis is characterized by the following:

Absence of clinical signs and symptoms of syphilis

Positive serologic tests for syphilis, including both nontreponemal and treponemal tests.

Two stages of latent syphilis are differentiated to guide treatment. Early latent syphilis is defined as seroconversion (or four-fold or greater increase in a nontreponemal test) during the past 12 months, without clinical evidence of syphilis. For treatment purposes, early latent syphilis is grouped with primary and secondary syphilis. Late latent syphilis refers to seroconversion after 12 months, and requires a different treatment regimen. The term “latent syphilis of unknown duration” is used when the timing of seroconversion cannot be established.8

Neurosyphilis

Clinically significant neurosyphilis develops in up 20% of patients with untreated early syphilis, but abnormal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can be found in a much higher proportion of patients with early syphilis. Neurosyphilis in AYAs is usually asymptomatic but may manifest as acute meningitis. Meningovascular syphilis is rare.

Asymptomatic neurosyphilis: Characterized by abnormal CSF, including pleocytosis, elevated protein, and positive CSF-venereal diseases research laboratory (VDRL)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree