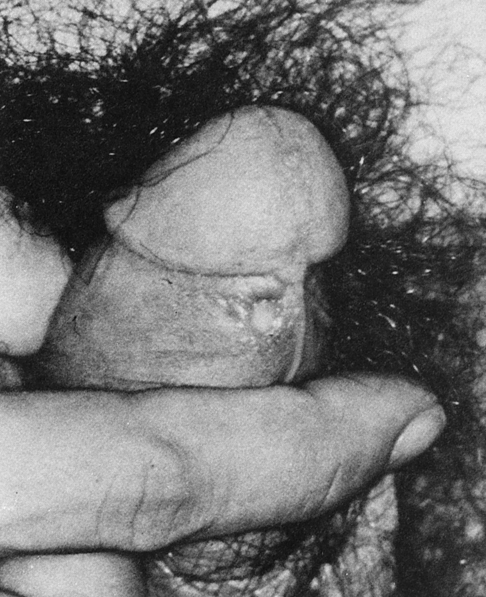

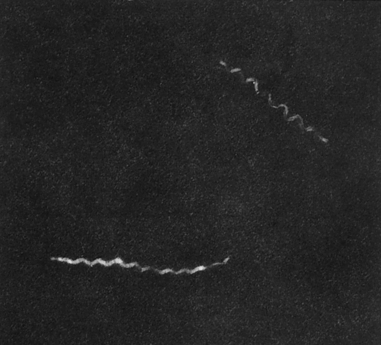

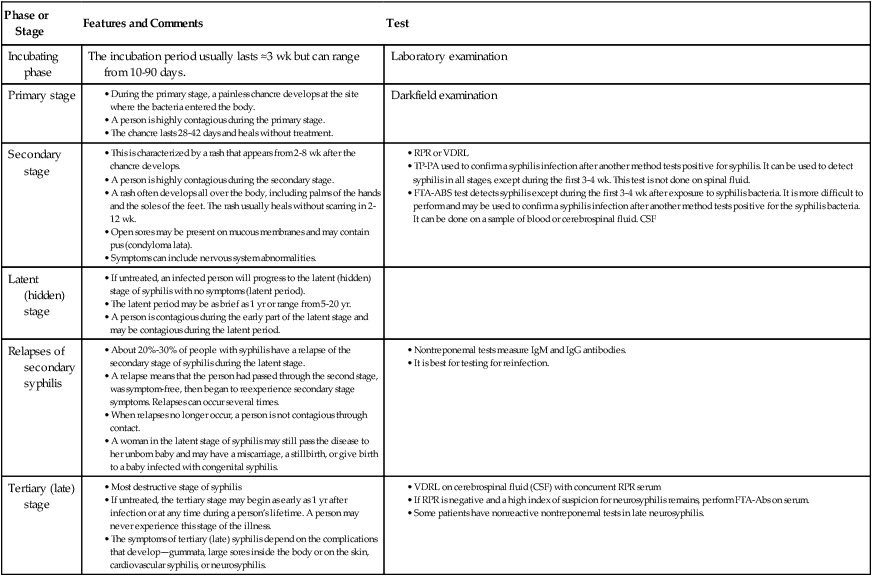

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader should be able to: • Describe the etiology; epidemiology; and signs and symptoms of primary, secondary, latent, and late (tertiary) syphilis. • Describe the origin and manifestations of congenital syphilis. • Explain the immunologic manifestations and diagnostic evaluation of syphilis. • Analyze a case study related to syphilis testing. • Correctly answer case study related multiple choice questions. • Be prepared to participate in a discussion of critical thinking questions. • Discuss the principles and clinical applications of the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) card test and VDRL procedure. • Discuss the principles and clinical applications of confirmatory syphilis testing, such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA) test. The disease syphilis was reported in the medical literature as early as 1495. In 1905, it was discovered that syphilis was caused by a spirochete type of bacteria, Treponema pallidum (originally called Spirochaeta pallida). The first diagnostic blood test for syphilis was the Wassermann test, a complement fixation test developed in 1906. This classic procedure (see www.mlturgeon.com, “Archives of Classic Procedures”) has subsequently been replaced by a variety of methods. In the treatment of syphilis, heavy metals, such as arsenic, were replaced by penicillin in the 1940s. Penicillin continues to remain the drug of choice for the treatment of this disease. T. pallidum is a member of the order Spirochaetales and the family Treponemataceae (Fig. 18-1). The genus Treponema includes a number of species that reside in human gastrointestinal and genital tracts. T. pallidum, Treponema pertenue, and Treponema carateum are human pathogens responsible for significant worldwide morbidity (Table 18-1). Yaws, pinta, and bejel are diseases caused by bacteria closely related to T. pallidum. Yaws is common in the Caribbean, Latin America, Central Africa, and the Far East. Pinta is found only in Latin America and infection is limited to the skin. Bejel is found in eastern Mediterranean countries, the Balkans, and the cooler areas of North Africa. Table 18-1 Untreated syphilis is a chronic disease with subacute symptomatic periods separated by asymptomatic intervals, during which the diagnosis can be made serologically. The progression of untreated syphilis is generally divided into stages—primary, secondary, latent (hidden), and tertiary (late) (Table 18-2). Table 18-2 At the end of the incubation period, a patient develops a characteristic, primary inflammatory lesion called a chancre at the point of initial inoculation and multiplication of the spirochetes. The chancre begins as a papule and erodes to form a gradually enlarging ulcer, with a clean base and indurated edge (Fig. 18-2). Generally, it is relatively painless. In most cases, only a single lesion is present, but multiple chancres are not rare. Within 2 to 8 weeks (but occasionally as long as 6 months) after the appearance of the primary chancre, a patient may develop the signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. In some patients, primary and secondary syphilis overlap and the chancre is still obvious. Other patients never notice the primary chancre and initially have manifestations of secondary syphilis (Fig. 18-3). Secondary syphilis usually resolves within 2 to 6 weeks, even without therapy.

Syphilis

Etiology

Bacteria

Associated Disease

T. pallidum

Syphilis

T. pallidum (variant)

Bejel

T. pertenue

Yaws

T. carateum

Pinta

Signs and Symptoms

Primary Syphilis

Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis