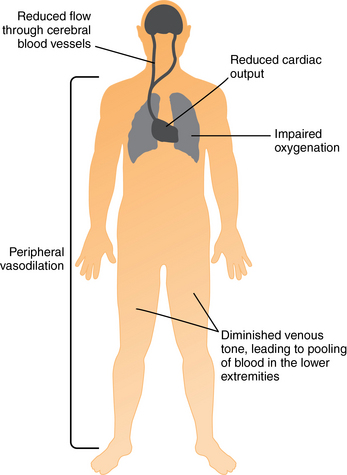

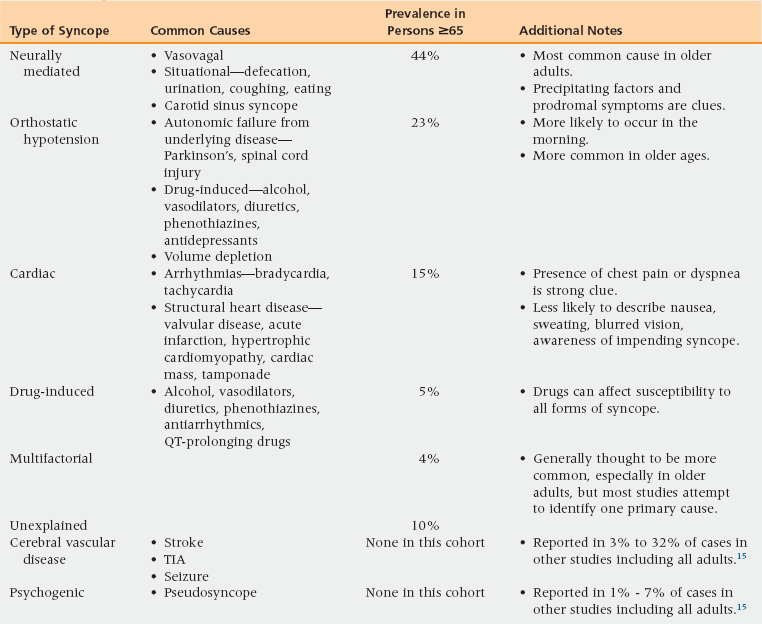

22 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe the physiologic mechanisms that give rise to a complaint of syncope. • Use key history and physical examination data to create a differential diagnosis for the patient experiencing syncope. • Identify and describe the presentation, prognosis, and treatment of the common causes of syncope in the elderly. Syncope is defined as the sudden loss of consciousness and postural tone with spontaneous recovery. It is distinct from dizziness, vertigo, seizures, prolonged decreased mental status, drop attacks without loss of consciousness, and cardiac arrest. During a 10-year period, approximately 6% of all adults have syncope. The prevalence rises steeply with age.1 Older patients are more likely to present to their primary care provider or the emergency department for evaluation of their syncope, and they more often have life-threatening causes.2 Syncope is not a disease, but it is a dangerous symptom whose underlying cause can be challenging to diagnose. In frail older adults it is more likely to lead to falls with injury and prolonged disability. Identification of the cause of syncope is important to allow treatment of the underlying disorder and prevent repeat events. The underlying pathophysiology leading to syncope is inadequate oxygenation of the cerebral cortex and reticular activating system, resulting in loss of consciousness. A variety of mechanisms lead to this outcome, but the final common pathway involves reduced blood flow or reduced oxygen-carrying capacity. Figure 22-1 is a graphic identifying the main physiologic factors that can lead to inadequate brain oxygenation. The differential diagnosis is extensive; many diseases and conditions can lead to this outcome. They fall into these general categories: neurally mediated (reflex) causes, orthostatic hypotension, cardiac causes, central nervous system diseases, and psychiatric disorders.3 In a study of 655 cases of syncope among community elderly, a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) was by far the greatest potential risk factor for syncope (odds ratio [OR] = 2.96). Use of cardiac medication (OR = 1.70) and a diagnosis of high blood pressure (OR = 1.50) were also significant predictors of a syncopal event.4 The cause of these associations is probably multifactorial, with side effects from medications and autonomic insufficiency as possible contributing factors. In addition to having more underlying chronic conditions and being on more medications than younger adults, older persons tend to have several age-related physiologic changes that increase their syncope risk. These include the following5: • Atherosclerosis (impairing dilation of cerebral blood vessels in the face of reduced blood flow) • Increased endothelin production (increasing vasoconstriction of cerebral arterioles) • Left ventricular dysfunction, caused by long-standing hypertension and/or heart disease (resulting in decreased cardiac output) • Cardiac valvular disease (increasing the likelihood of arrhythmias and heart block) • Blunting of autonomic responses (predisposing the person to orthostatic hypotension Causes of syncope can be categorized as neurally mediated, orthostatic, cardiac, cerebrovascular, psychogenic, or multifactorial (Table 22-1). Some studies include drug-induced as a cause, though one could argue that drugs may cause increased susceptibility to all forms of syncope. Many etiologies of syncope go undiagnosed. Older patients are more likely to have multiple etiologies. TABLE 22-1 Differential Diagnosis of Syncope TIA, transient ischemic attack. Source: Ungar A, Mussi C, Del Rosso A, et al. for the Italian Group for the Study of Syncope in the Elderly. Diagnosis and characteristics of syncope in older patients referred to geriatric departments. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54(10):1531-6. Neurally mediated syncope is considered the most common form in all ages, including the geriatric population.6,3 This usually involves the initiation of reflexes that lower blood pressure through venous pooling in the legs, or slow the heart rate through stimulation of the vagus nerve. A variety of physiologic stimuli can trigger this reflex: urination, defecation, cough, gastrointestinal stimulation (especially pain), stimulation of the carotid sinus (e.g., by a tight collar), and intense emotions. Neurally mediated syncope is often considered a benign etiology, but given its high prevalence it can be responsible for a large burden of morbidity and mortality. Multiple contributing factors may lead to this form of syncope. The most common type of neutrally mediated syncope is vasovagal or neurocardiogenic syncope. This typically involves prolonged standing, emotional distress, or exertion in warm environments causing the peripheral venous pooling and a drop in blood return to the heart. As the heart recognizes a sudden decrease in preload, it tries to compensate by contracting harder. The quick increase in contraction activates mechanoreceptors in the ventricles that start a reflex mechanism causing the central nervous system to stimulate vasodilation and bradycardia. As the drop in cardiac output becomes more profound, syncope may occur.7 When suspecting a neurally mediated syncope, look for associated symptoms of nausea and/or vomiting, and a history that includes prolonged standing, hot environments, and/or unpleasant situations. You should be cautious to not assume this diagnosis in patients with known heart disease or repetitive episodes of syncope. Carotid sinus syndrome is often listed as a cause of syncope.8 This is because manual stimulation of the carotid sinus can, in susceptible individuals, stimulate neurally mediated syncope. A few individuals (e.g., wearing tight collars) have true carotid sinus syncope; however, in most cases the provocation of syncope with carotid sinus massage indicates a susceptibility to neurally mediated syncope rather than a diagnosis. Orthostatic hypotension is a drop in arterial pressure that occurs when an individual moves to an upright position. Typically, the autonomic nervous system rapidly compensates for this by increasing the venous tone in the legs; when this system fails, syncope may occur. When the circulating blood volume is depleted, as in dehydration, orthostatic hypotension and syncope may occur even with appropriate autonomic compensation.9 This diagnosis should be considered in individuals who are on medications that can predispose to orthostasis, who have reason because of illness or blood loss to be dehydrated, or who have autonomic insufficiency from a neurologic disorder such as parkinsonism. A typical case occurs soon after standing up or after prolonged standing in a hot, crowded environment. The traditional definition of orthostatic hypotension is a drop in systolic blood pressure of ≥20 mmHg, or a drop in the diastolic pressure of ≥10 mmHg, 3 minutes after assuming the upright position. While this definition remains in use, numerous studies have demonstrated that syncope resulting from orthostatic cerebral hypoperfusion can occur when the standard criteria for orthostasis are not met. Three general mechanisms can lead to this orthostatic syncope (or near-syncope) that does not meet the definition of orthostatic hypotension: early orthostasis, late orthostasis, and impaired cerebral perfusion with only mild decreases in systemic blood pressure.10 Atherosclerotic narrowing of the carotid and/or vertebral arteries may increase the susceptibility to syncope from these mechanisms. Cardiac syncope occurs when cardiac function is reduced by arrhythmia, myocardial death, or outflow obstruction, leading to decreased blood flow to the brain. Several studies have shown an increase in overall mortality and sudden death among patients with cardiac syncope compared to patients with syncope from other causes.1,11 A cardiac cause should be considered when syncope is preceded by palpitations or chest pain, or when it occurs during exertion. Patients with known severe structural heart disease should be considered to have cardiac syncope until proven otherwise. Cerebrovascular disease is a rare but plausible cause of syncope. Most TIAs or strokes do not cause loss of consciousness, but occasionally this can occur. There is a low yield in the use of neurologic testing in the evaluation of individuals with syncope unless it is directed at those with neurologic findings on initial evaluation.3,12 Psychiatric causes should be considered in patients with repetitive syncope of unknown origin after cardiac causes have been effectively ruled out.13 They are more common in younger patients. Prodromal symptoms, such as dizziness, are common. Several hypotheses exist regarding the connection between psychiatric disorders and syncope. Hyperventilation can increase susceptibility to neurally mediated syncope. There is also a term called pseudosyncope, which has been used to describe patients with syncope of unknown but presumed psychiatric origin, who have no pathologic findings on examination and documented syncope without any change in blood pressure or pulse.14 Drugs should always be considered as a cause or contributing factor in syncope. The older population is particularly sensitive to drug effects and is more likely to take more of them. Drugs such as alcohol, vasodilators, diuretics, phenothiazines, and antidepressants may lead to orthostatic hypotension as a cause of syncope. Antiarrhythmic drugs can lead to bradycardia, and QT-prolonging drugs may lead to torsades de pointes. There are many categories of drugs that can lead to a prolonged QT interval including antiarrhythmics, vasodilators, psychotropics, antimicrobials, nonsedating antihistamines, and methadone.3

Syncope

Prevalence and impact

Risk factors and pathophysiology

Differential diagnosis and assessment

Neurally mediated syncope

Orthostatic hypotension

Cardiac syncope

Cerebrovascular disease

Psychogenic syncope

Drug-induced syncope

Oncohema Key

Fastest Oncology & Hematology Insight Engine