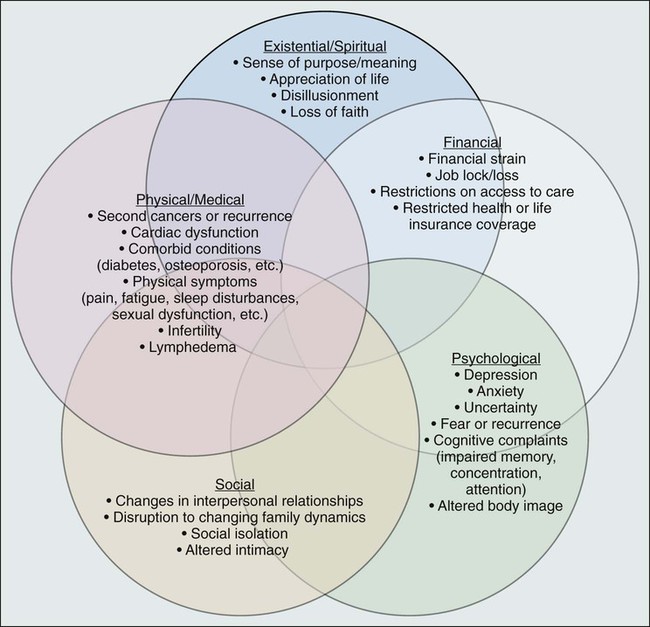

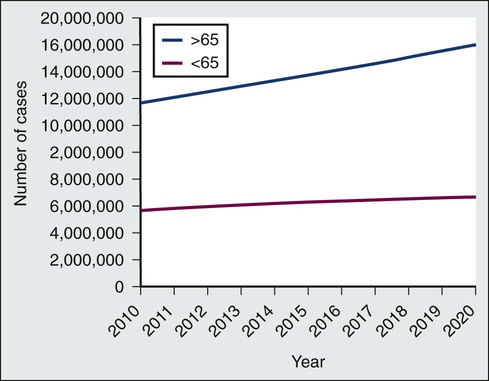

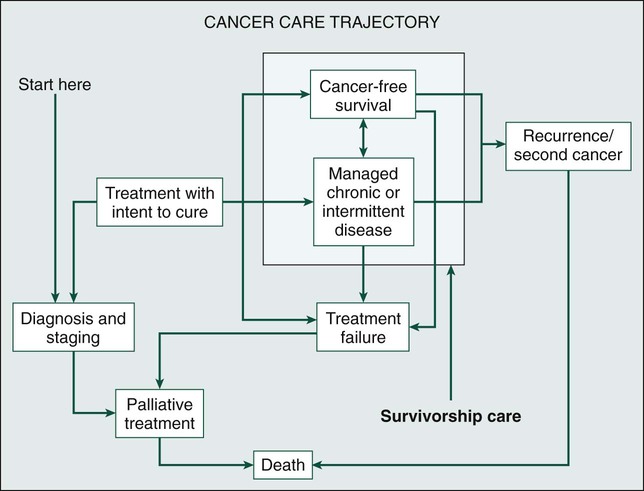

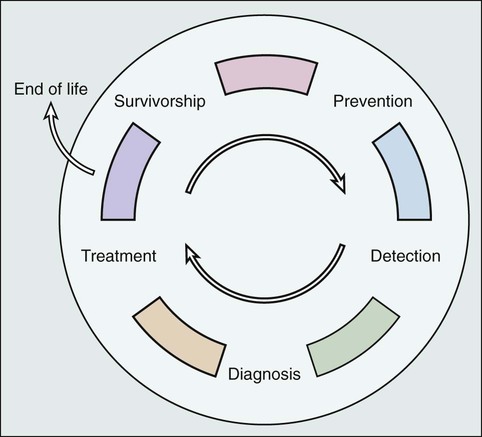

Laura P. Forsythe, Erin E. Kent and Julia H. Rowland • The number of persons in the United States who are living with a cancer history will continue to rise during the next decade, reaching 18 million by the year 2022, and approximately two thirds of cancer survivors will be older than 65 years. • Cancer survivorship, which is the period between the end of active cancer treatment and a recurrence or death from some other cause, is a distinct phase on the cancer control continuum with its own health care demands. • The Institute of Medicine has identified four essential components of survivorship care considered to be critical for optimizing health after cancer: (1) detection of recurrent cancers, new cancers, and late effects of cancer and its treatment; (2) intervention for the long-term and late effects of cancer and its treatment; (3) prevention of recurrent and new cancers and other late effects; and (4) coordination between providers to ensure that all survivors’ health needs are met. • Cancer and its treatment are associated with a variety of long-term adverse effects (e.g., pain, fatigue, sexual dysfunction, and bladder or bowel problems) or late-occurring adverse effects (e.g., recurrence/second malignancies, heart disease, diabetes, or osteoporosis) that can affect all aspects of a survivor’s life: physical, psychological/emotional, social, financial, and existential. • Most cancer survivors are remarkably resilient and recover well after cancer, but some persons struggle with effects of their cancer and/or treatment. • Cancer represents a “teachable moment” for many survivors, when clinicians have the opportunity to effectively promote healthy lifestyles and behaviors. • Planning for posttreatment health and care, including use of treatment summaries and follow-up care plans and communicating these summaries and plans to survivors and their other care providers, is key to coordinated, comprehensive cancer care. • Screening family caregivers for psychosocial distress and referring them for supportive care as needed can improve survivors’ outcomes. Because of the progress made in early detection and treatment of cancer, as well as the aging of the population, a growing number of people are living with and beyond a diagnosis of cancer (Fig. 56-1).1 Consequently, clinicians today are faced with not only diagnosing and treating cancer but also addressing the ongoing medical and psychosocial challenges that arise after cancer treatment ends. Although persons with a history of cancer are considered cancer “survivors” from the point of diagnosis for the remainder of their lives,2 this chapter is focused on survivorship, defined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) as representing a distinct phase of the cancer care trajectory.3 Survivorship care begins at the completion of primary cancer treatment and continues until cancer recurrence, a second cancer, or death (Fig. 56-2); this conceptual approach to care requires providers to think about survivorship from the initiation of cancer treatment to engender optimal posttreatment health outcomes. This chapter provides a historical overview of the field of cancer survivorship and describes the U.S. survivor population. We then review numerous consequences of surviving cancer and the implications for survivorship care. Different models for delivery of survivorship care and current care delivery practices are reviewed. Finally, we also briefly discuss the needs of cancer survivors’ caregivers and family members. Comprehensive, long-term follow-up care consistent with IOM recommendations has been the exception rather than the norm.3,4 When applied in a clinical setting, the information in this chapter can facilitate more comprehensive, effective, efficient, and patient-centered care for the growing population of cancer survivors. Before the 1970s, survival rates from all cancers were relatively low.5,6 Effective treatment options were rare and entailed serious adverse effects.7 Advances in earlier tumor detection, increasingly efficacious therapies, and better supportive care led to increases in 5-year survival rates for several cancers.8,9 The recent overall 5-year relative survival rate in the United States is approximately 67%.10 Improved survival rates and growth in the population of survivors (Fig. 56-1) have helped to motivate a surge in cancer survivorship research.11 The inclusion of this chapter on cancer survivors in this book underscores the importance of the findings from this rapidly expanding field and their implications for clinical practice. The launch of the survivorship movement is often attributed to two events. In 1985, the New England Journal of Medicine published a piece by a young physician, Dr. Fitzhugh Mullan, entitled “Seasons of Survival” in which he described his personal experience with cancer.12 The following year, the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship was founded and proposed a new definition of the term “cancer survivor.”2 Until this time, the term “cancer survivor” referred to someone who had remained disease-free for a minimum of 5 years. The intent of the founders of the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship in advancing a revised definition was twofold: first, to convey a message of hope to those newly diagnosed with cancer that life was not over, and second, to promote a dialogue between patients and their physicians about the impact that different treatment options might have on survivors’ future health and function (i.e., foster patient-centered decision making). Although some persons with a cancer history do not consider themselves to be survivors,15–15 the language has helped launch a survivorship movement globally. Several national reports brought increased visibility to cancer survivorship: the President’s Cancer Panel highlighted the lack of information about survivors’ needs,16 and the IOM described the challenges in caring for pediatric cancer survivors,17 the need for comprehensive psychosocial care for cancer survivors,18 and the challenges faced by survivors who are transitioning off treatment.3 Collectively these reports contributed to wide recognition of cancer survivorship as a unique place on the cancer control continuum. An estimated 13.7 million Americans with a history of cancer were alive in the United States as of January 1, 2012,19 representing approximately 4% of the population.20 By 2022, this number is expected to increase to about 18 million.19 More than half of survivors have been living with their cancer for more than 5 years.1 Approximately 60% of cancer survivors are 65 years or older, and this proportion is steadily growing (Fig. 56-1).1 Additionally, the number of nonwhite survivors is expected to grow disproportionately.21 As is evident in longitudinal studies of childhood cancer survivors,22,23 survivors often confront health effects from cancer or its treatment that can be debilitating, persistent, and difficult to treat.24 Thus cancer is increasingly being viewed as a chronic condition.25 The IOM has delineated four essential components of survivorship care (Box 56-1) that are considered critical for optimizing health after cancer: (1) detection of recurrent cancers, new cancers, and late effects of cancer and its treatment; (2) intervention for the long-term and late effects of cancer and its treatment; (3) prevention of recurrent and new cancers and other late effects; and (4) coordination between providers to ensure that all survivors’ health needs are met. Although completion of cancer treatment is often eagerly anticipated and celebrated, termination of cancer treatment and the transition to survivorship care can be difficult for many survivors and their families.3 Common challenges include worry that cancer will return,26,27 loss of the supportive environment of the cancer treatment team,28,29 a diminished sense of well-being because of the cancer or treatment effects, concern that ongoing symptoms may indicate cancer recurrence,30,31 confusion about the next steps in their care,29,31 and demands from family and friends that survivors quickly return to “normal” after completion of treatment.32 Thus preparing survivors for the end of cancer treatment, including discussing the expected course of both cancer-related symptoms and cancer follow-up care, may ease the survivorship transition.32 Resources such as the National Cancer Institute’s Facing Forward series (http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/ff_series.html) can help survivors and their families anticipate what to expect and plan for life after treatment. Based on information from the U.S. Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results cancer registries, 8% of cancer cases diagnosed between 1975 and 2001 and 16% of cancers diagnosed in 2002 alone occurred in persons with a prior history of cancer.33 The increase is due in large part to the fact that many survivors are living long enough after their initial cancer diagnosis to have a second (or multiple) malignancy. Survivors of multiple cancers report worse physical and mental health than do survivors of one cancer or persons who have never had cancer.34,35 The genetic and iatrogenic factors that contribute to second cancers are covered in detail in Chapter 12. This chapter addresses clinically relevant information regarding surveillance for recurrent cancers, screening for second cancers, and communicating with survivors about these issues. Guidance regarding the nature and frequency of surveillance testing for recurrent cancers is provided by the American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO)36 and/or the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)37 for breast, colorectal, hematologic, ovarian, uterine, head and neck, and gastric cancers. Such guidelines primarily take into consideration the evidence available on survival, although health-related quality of life, possible adverse effects, the consequences of false-positive test results, and costs are also considered when possible. Depending on the cancer site, guidelines are based on varying amounts of supporting scientific evidence. The breast and colorectal surveillance guidelines have the largest body of scientific evidence, yet there is recent debate regarding whether these guidelines should be revisited now that we have more efficacious treatments for metastatic disease that may increase the utility of earlier detection of recurrent or metastatic disease. Variable surveillance practices38 may be attributable in part to the complete lack of surveillance recommendations for many cancers. Research on breast and colorectal survivors suggests that recommended surveillance tests are underutilized, particularly among survivors who are older, nonwhite, underinsured, and have a high comorbidity burden.39–44 Concurrently, there appears to be overuse of a number of nonrecommended surveillance tests.40,45,46 Reducing the use of nonrecommended biomarker and imaging tests in surveillance for breast cancers treated with curative intent is one of ASCO’s top five ways to improve the quality and reduce the cost of oncology care.47 Regarding screening for new malignancies, cancer survivors should, at a minimum, be advised to adhere to the expert consensus recommendations for cancer screening in the general population, such as those provided by the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force48 or the American Cancer Society.49 Some survivors, however, may need more frequent cancer screening depending on the nature of their cancer and treatment exposures. For example, because of their elevated risk of breast cancer, female survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma treated with chest radiation50 warrant consideration for annual mammography beginning at an earlier age than is recommended for the general population.51 Although some studies suggest that survivors are more likely than persons without a cancer history to be screened for other cancers,52,53 other studies have found that survivors at high risk for second malignancies often fail to be screened according to recommendations.56–56 Furthermore, as the population of older adults grows, more guidance will be needed regarding when to stop cancer screening and surveillance. Decisions about cancer screening should be made through an individualized, informed, shared decision-making process that takes into account the survivor’s age, health status, and likely ability to benefit from the screening results.57 Finally, survivors tend to misestimate their risk of recurrence or second cancers,58,59 and fear of cancer recurrence is common.27 Misestimating risk can lead to increased anxiety, over- or underutilization27 of follow-up care, or noncompliance with recommended follow-up. Consequently, providers should clearly communicate with survivors about their risk of new or recurrent cancers and, when possible, which signs or symptoms may be indicators of cancer’s return, a discussion that survivors indicate they desire.58 To inform such conversations, more advanced risk prediction models that accurately identify which survivors will experience a recurrence will be needed. The cancer experience does not end when treatment does: cancer and its treatment (including surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and newer drug therapies) can affect virtually every aspect of a person’s life (see Fig. 56-3). Some effects are acute and transient (e.g., hair loss associated with chemotherapy and postsurgical incision pain). Others are longer term, arising during treatment and persisting months or even years after therapy is done (e.g., fatigue, memory problems, peripheral neuropathy, and sexual dysfunction). Many of these symptoms will ultimately resolve; however, some changes can be permanent (e.g., infertility and amputation). A third category of effects are those that are late occurring, generally defined as manifesting 6 months or more after treatment. In addition to recurrence or second cancer,33 risk for a number of other health conditions (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and osteoporosis) is also increased.60,61 Depending on the age of the survivor, these conditions may be of more concern than the cancer.62 Cancer survivors report worse physical functioning, higher rates of disability, and more unemployment than do persons without a cancer history and/or persons with other major disease diagnoses.65–65 To complicate matters, research suggests that lingering physical symptoms often occur in clusters (e.g., problems with sleep, fatigue, and pain),66 and greater cancer-related symptom burden is associated with increased risk of poor quality of life.67 In contrast with the lingering physical sequelae, by 1 or more years after treatment, most cancer survivors report emotional well-being equivalent to or better than their peers without a cancer history.68 Although a significant subset of survivors continue to experience emotional distress, this observation underscores the remarkable resilience shown by most survivors. Three persistent effects of cancer are worth discussing here because they are troubling and commonly experienced across cancer types: fatigue, depression, and memory problems. Although fatigue during treatment and its causes are addressed in Chapter 45, clinicians need to be aware that an estimated quarter to a third of survivors have posttreatment fatigue.69 Data among breast cancer survivors suggest that up to 20% of women may have problems with fatigue as long as 10 years after cancer therapy.70 Cancer-related fatigue often does not respond to increased sleep. At present, the most effective intervention for fatigue is exercise,71 which is beneficial on many levels, as discussed in a subsequent section. Furthermore, reassurance that fatigue can linger after treatment ends is important to reduce fears that this symptom indicates progressive or recurrent disease. The prevalence of depression among cancer survivors varies depending on the type and stage of cancer, age of the patient, treatments received, and the timing of and measurements used to assess symptoms. Research suggests that up to 38% of patients with cancer experience major depression and up to 58% experience subclinical depressive symptoms72; the prevalence among posttreatment survivors is not well documented. Younger age, female gender, and prior history of depression are associated with a higher risk of depression among cancer survivors,73 yet many survivors experience depression for the first time after a cancer diagnosis.74 Although the reasons are not well understood, emerging epidemiologic evidence suggests that cancer survivors have higher rates of suicide years after treatment compared with their peers who do not have a cancer history.75,76 Patients and clinicians need to understand that cancer and its treatment can induce depression because many persons believe that their symptoms are a sign of poor coping or mistakenly assume that depressed mood is expected in the face of cancer.74 Depression may result from changes in hormonal milieu, alterations in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis regulation, inflammatory processes, or a combination of these as a result of (e.g., premature menopause resulting from chemotherapy) or as a direct consequence of (e.g., exposure to interferon) treatment.77,78 Both standard psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions have proven effective in treating cancer-related depression.79 Prompt diagnosis and referral for treatment, including follow-up to ascertain that recommended interventions were effective, are crucial to reduce unnecessary suffering. Although it has been poorly studied for years, neurocognitive dysfunction (i.e., difficulty remembering things, thinking clearly, and focusing attention, commonly referred to by patients as “chemo brain” or “chemo fog”) is a real and persistent effect of cancer treatment80 that may affect ≥14% of survivors.81 Although the underlying mechanisms are not well understood, genetic predisposition and changes in neurochemistry and brain structure may play a role.82 A number of promising interventions have been developed to help childhood cancer survivors in managing cognitive problems that result from cancer,83 and more recently, promising cognitive behavioral therapy interventions are being explored among adult survivors.84 Given the commonality of long-term and late effects and the underrecognition or underestimation of these problems in clinical settings,85 consistent assessment of current function, provision of treatment as needed, calculation of risk for subsequent problems, and addressing risk for subsequent problems are key components of quality posttreatment care. At present, standards for distress screening at the time of diagnosis are provided by NCCN (NCCN Guidelines),86 which are promoted by ASCO as part of their Quality Oncology Practice Initiative87 and will become part of the credentialing criteria within the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer by 2015.88 However, guidance on and standards for evaluation of health-related quality of life and function at transition to recovery is lacking. Although consensus is currently lacking on what evaluation tools to use, a number of tools exist to help clinicians with this activity. For example, the NCCN distress thermometer86 measures global distress level and identifies aspects of well-being that may contribute to distress (e.g., physical symptoms, social problems, and financial concerns); the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement System (PROMIS; available without cost at www.nihpromis.org) permits evaluation of function across a variety of physical and emotional domains, as well as comparison of individuals to others with other chronic illnesses89; and the Patient-Reported Outcome Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) measure,90 a tool currently being tested in the clinical trial setting, surveys patients to rate the presence and degree of impairment resulting from a wide range of common cancer-related symptoms. Research is needed to inform evidence-based methods of screening for late and long-term effects during the posttreatment phase that are sensitive, effective, and feasible. Few clinicians will have the skills, time, or desire to manage the full array of potential long-term and late effects encountered in their survivor population. Rather, a team approach with broad referral to specialized support staff and coordination capacity is critical to provide optimal care for these persons. Many survivors benefit from referral to supportive interventions after cancer treatment ends. Although professional counseling or support groups are used by fewer than 15% of survivors,91 a variety of different kinds of intervention groups (e.g., cognitive behavioral, exercise, supportive expressive, educational, and psychodynamic) that are operated by diverse staff (e.g., nurses, social workers, psychologists, and physicians) and include different participants (e.g., specific cancer type or mixed, advanced cancer, or early cancer) and, most recently, different venues (e.g., face-to-face vs. online) have been shown to improve knowledge of the effects of cancer and their management, reduce symptom burden, and enhance physical function and quality of life.92–97 Although debate continues about whether such interventions prolong survival,98 their capacity to reduce suffering without the adverse effects observed for many pharmacologic interventions warrants recommendation of these services. It is important for oncology clinicians to have information about such resources available in the community. Although the cancer control continuum is often presented in a linear fashion, Rowland and Bellizzi99 portray the continuum as a cyclical process (Fig. 56-4), which emphasizes both the need for surveillance and follow-up care for cancer survivors after initial treatment has concluded and the potential for the cancer experience to be viewed as a “teachable moment.”32,100 Survivorship care offers opportunities for changes in dietary behaviors, physical activity, smoking, and stress management that may reduce survivors’ risk of recurrence, second malignancies, late effects, and comorbid conditions. The evidence on behavioral factors for cancer prevention in the general population covered in Chapter 23 of this volume is also relevant for cancer survivors. Among survivors specifically, observational studies suggest that smoking cessation, increased physical activity, and weight control may reduce the risk of cancer recurrence, cancer-specific mortality, and overall mortality,103

Survivorship

Early assessment and intervention or referral for these effects has the potential to significantly reduce the burden of cancer.

Early assessment and intervention or referral for these effects has the potential to significantly reduce the burden of cancer.

Ideally, planning for optimal survivorship starts at the time of diagnosis when decisions are being rendered that have the potential to affect the remainder of a survivor’s life.

Ideally, planning for optimal survivorship starts at the time of diagnosis when decisions are being rendered that have the potential to affect the remainder of a survivor’s life.

Introduction

Historical Background of Cancer “Survivorship”

Cancer Survivors in the United States

Posttreatment Survivorship Care

Detection of Recurrence and Second Cancers

Assessment and Treatment of Long-Term and Late Effects

Overview of Long-Term and Late Effects

Assessment and Treatment of Long-term and Late Effects

Prevention of New or Recurrent Cancers and Late Effects of Cancer

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Survivorship