20 Surveillance and Detection of Recurrence of Breast Cancer

Introduction

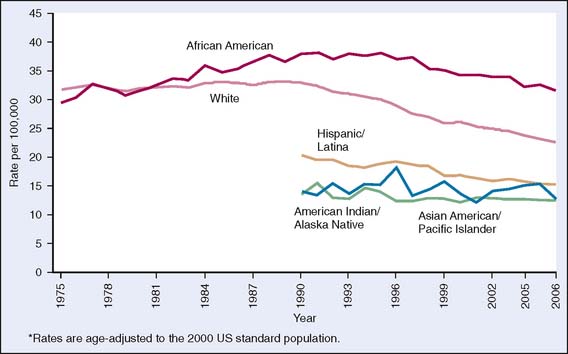

The diagnosis and treatment of early stage breast cancer have improved dramatically over the last two decades, resulting in declining breast cancer mortality1 (Fig. 20-1). Currently, there are over 2 million breast cancer survivors in the United States, accounting for 23% of all cancer survivors, which increases the importance of continued care and surveillance. Here we discuss the current recommendations and evidence for post-treatment surveillance in breast cancer survivors.

Figure 20-1 Trends in female breast cancer death rates* by race and ethnicity, United States, 1975–2006.

(From American Cancer Society, Breast Cancer Facts and Figures 2009–2010, Figure 4b, p. 6. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc. Data source: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009. For Hispanics, information is included for all states except Connecticut, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Vermont, and Virginia and the District of Columbia.)

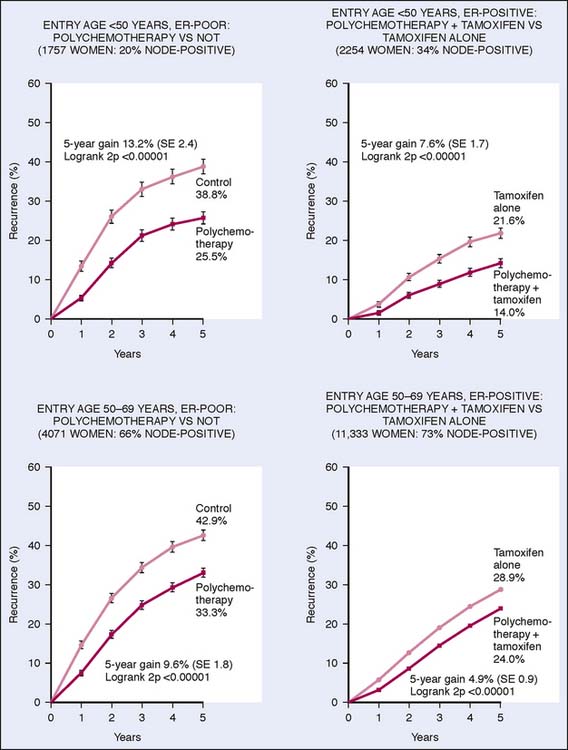

Although surveillance during the first 5 years after cancer diagnosis and treatment in solid tumors is considered crucial because it is the time with the highest risk for recurrent disease, this timeline does not fit well in breast oncology. Depending on the biologic characteristics of the primary tumor, the peak incidence of recurrence varies, and in all settings late recurrences can occur. There is a clear difference in the relapse pattern between estrogen receptor (ER)-positive and ER-negative disease. In ER-negative cancer, the relapse pattern more closely follows the pattern of other solid tumors, with peak annual incidence of recurrence between 18 and 24 months. On the other hand, the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group meta-analysis of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer treated with tamoxifen demonstrated a delay in recurrences, with rates three times higher at 15 years post-treatment when compared with 5 years2 (Fig. 20-2).

Figure 20-2 Effects of therapy on early breast cancer.

(From Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative group: Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 365(9472):1687, 2005.)

The Evidence Behind Current Surveillance Guidelines in Breast Cancer

Comprehensive guidelines for post-treatment surveillance in breast cancer have been published and updated in 2006 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).3,4 Several other groups have published evidence-based recommendations, which are largely similar to the ASCO guidelines. Characteristic of all the recommendations is a paucity of prospective randomized data supporting a given surveillance protocol. However, a minimum follow-up requirement comparable to other solid organ tumors has been established. Scheduled history, physical examination, yearly mammograms, and breast self-examinations form the basis of surveillance in breast cancer and are considered the standard of care in the United States. The best interval for these measures was decided empirically (Table 20-1).

Table 20-1 ASCO Guidelines for Post-treatment Surveillance

| Follow-Up Care Test | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Medical history and physical examination | Visit your doctor every 3–6 months for the first 3 years after the first treatment, every 6–12 months for years 4 and 5, and every year thereafter. |

| Post-treatment mammography | Schedule a mammogram 1 year after first mammogram that led to diagnosis, but no less than 6 months after radiation therapy. Obtain a mammogram every 6–12 months thereafter. |

| Breast self-examination | Perform a breast self-examination every month. This procedure is not a substitute for a mammogram. |

| Pelvic examination | Continue to visit a gynecologist regularly. Women taking tamoxifen should report any vaginal bleeding to their doctor. |

| Coordination of care | About 1 year after diagnosis, continue to visit your oncologist or transfer care to primary care doctor. Women receiving hormone therapy should talk with their oncologist about how often to schedule follow-up visits for reevaluation of their treatment. |

| Genetic counseling referral | Tell your doctor if there is a history of cancer in your family. The following risk factors may indicate that breast cancer could run in the family: • Two or more first-degree or second-degree relatives (grandparent, aunt, uncle) diagnosed with breast cancer |

Despite recommended guidelines, actual surveillance practices differ considerably among practitioners as documented by a recent study by Keating and colleagues.5 In this study, 50% of breast cancer survivors saw a medical oncologist in the first year, but only 27% of patients saw an oncologist yearly for the first 3 years. The patients who were seen by an oncologist were more likely to have tumor markers checked and computed tomography (CT) scans and chest x-rays performed compared with patients seen by primary care practitioners. The rate of testing has declined with time in all patients in this study. However, adherence of clinicians to the proposed surveillance guidelines has also been shown to lead to significant savings in health care costs and should be encouraged6 (Box 20-1).

Detecting Locoregional Recurrences

In-breast tumor recurrences after breastconserving surgery and radiation therapy occur at a rate of 1% to 2% per year. Postoperative scarring makes it difficult to interpret mammograms at the lumpectomy site. Further compounding the problem is local scarring, which often continues for years after surgery. With mammography, 25% to 45% of ipsilateral recurrences can be detected. The sensitivity of mammograms increases in the presence of microcalcifications.7 In the case of a palpable suspicious local lesion, a needle biopsy may offer the most cost-effective method of diagnosing a breast cancer recurrence, thus preventing extensive imaging workup, which in the end may be inconclusive. Ultrasound evaluation of any palpable mass is considered routine as well, similar to its role in primary breast cancer detection.

One of the important questions in surveillance for locoregional disease is who is the one who detects the recurrence—the patient or the physician. A recent meta-analysis of 12 studies involving 5045 patients showed that 40% of patients with locoregional recurrences were diagnosed during routine clinic visits or routine testing, whereas the remaining 60% of patients developed symptomatic recurrences before their scheduled visits with clinicians.8 Therefore, a monthly breast self-examination is part of the ASCO recommendations, although it has not been prospectively evaluated in breast cancer survivors (Fig. 20-3). In previously unaffected women, many randomized trials and a meta-analysis9 showed no benefit in mortality for breast self-exams. The largest of these evaluated more than 250,000 Chinese women who were not routinely screened with yearly mammograms. In this population, a breast self-exam did not offer a survival benefit.10 Meta-analysis of published data on breast self-exams in patients without a personal history of breast cancer did not show an improvement in overall survival or an improvement in quality of life. Moreover, the specificity and sensitivity of clinician breast exams in the post-treatment period are also not known.

(From American Cancer Society, How to Perform a Breast Self Examination. http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_6x_How_to_perform_a_breast_self_exam_5.asp?sitearea=.)

Currently, insufficient evidence exists to support additional radiologic studies for locoregional surveillance of the asymptomatic breast beyond the recommended clinician exams, self-exams, and annual mammograms. The role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in surveillance of the asymptomatic treated breast has not been determined, although MRI has demonstrated enhanced breast cancer detection in unaffected women whose lifetime risk is 20% or greater.11 These data suggest that affected women with this same risk profile may benefit from an MRI in addition to mammogram for secondary surveillance. In the setting of suspected locoregional recurrence, additional radiologic studies can be considered with some evidence for them. 18Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) has been compared primarily with MRI in the evaluation of locoregional recurrences, including lymph node metastases. In a small case series by Hathaway and coworkers,12 nine patients with regional recurrence were evaluated. MRI detected recurrent disease in five cases and was indeterminate in four. PET scan identified all nine patients. In a larger study of 32 patients, MRI had a sensitivity of 79% and specificity of 94% compared with 100% and 72% for PET scan, respectively.13

Early detection of local recurrence of breast cancer is anticipated to enhance the survival of the patient by reducing dissemination and progression to metastatic disease. The site of locoregional recurrence influences survival as well. The 5-year overall survival rate with a locoregional recurrence confined to the breast parenchyma or skin of the ipsilateral breast was 60% compared with 24% for recurrence involving regional nodes or recurrence in the non-breast skin of the ipsilateral chest wall.14 Therefore, even without clear evidence-based efficacy measures to detect locoregional disease, breast self-examination, clinician examination, and mammographic screening have been adopted into post-treatment surveillance guidelines.

Detecting Asymptomatic Systemic Metastases

For continued surveillance of cancer survivors, one has to take into account the pattern of recurrence. In breast cancer, bone, subcutaneous tissue, lung, liver, and brain are most commonly targeted. A thorough review of systems during surveillance visits should include these organ systems in detail to rule out concerning symptoms. In the truly asymptomatic setting, the increase in diagnostic modalities available to clinicians makes it increasingly important to address the extent and intensity of radiologic and laboratory surveillance that would benefit the patient, without causing unnecessary testing or anxiety. In a prospective randomized trial of the GIVIO (Interdisciplinary Group for Cancer Care Evaluation [Italy]) investigators in Italy, over 1300 patients were assigned either to intensive follow-up that included bone scans, liver ultrasounds, chest x-rays, and laboratory studies at predefined intervals or to history, physical examinations, and yearly mammograms performed with the same frequency.15 At a median follow-up of 71 months, the investigators found no difference in the overall survival rate or in the quality of life between the two groups. In a similar study, Roselli Del Turco and colleagues16 compared standard follow-up with the addition of chest x-ray and bone scan every 6 months for 5 years. A difference in detection of bone and thoracic metastases was seen between the two groups as would be expected, but again no difference in overall mortality was seen. In both studies, authors did not recommend intensive follow-up in breast cancer surveillance. Ten-year update of the GIVIO group’s study confirmed the lack of survival advantage with intensive follow-up protocol.17

Historically, minimal emphasis has been placed on the early detection of asymptomatic metastatic recurrence owing to the lack of curative options for this setting. However, with increasingly improved therapeutic options, including biologic agents whose potency may be impacted by overall disease burden, it remains a research imperative to investigate whether oligometastatic disease can be identified by a more intensive screening protocol with resultant improved survival outcomes. This could be seen as a theoretical B0 state similar to prostate cancer (disease detected by elevation of prostatespecific antigen only according to the Whitmore-Jewett staging system), equivalent to success with early intervention in advanced prostate cancer. Given the lack of current evidence, however, intensive radiologic screening cannot be justified or recommended (Box 20-2).