Location

No.

Fistula

4

Enteroenteric

3

Enterocutaneous

1

Intestinal tract

28

Ileum

2

Cecum

2

Descending colon

1

Sigmoid colon

1

Rectum

6

Anal canal

8

Anal fistula

8

7.3 Preoperative Preparation

7.3.1 Specific Medical Problems

Anemia, hyperglycemia, and electrolyte abnormalities should be discovered and remedied prior to operation.

7.3.2 Stoma Site Marking

In a patient with rectal amputation, consultation with an enterostomal therapist should be made to assist in the placement of the proposed stoma. Ideally the site should be located over the rectus muscle on a flat area from deep skin folds and bony prominences. The surface of the abdomen should be evaluated in the supine, sitting, and standing positions as this will often demonstrate skin folds and creases not evident in the other position. Finally, the patient’s belt line is determined and every effort is made to place the stoma below it.

7.3.3 Preoperative Antibiotics

Intravenous prophylactic antibiotics should be administered 1 h prior to surgery so that maximal tissue antibiotic levels are achieved at the time of the skin incision.

7.4 Preoperative Examination

The presence of a complex fistula, an associated stricture, and perineal pain prevents a thorough examination of the anus and perineal areas, thus making diagnosis of a concomitant carcinoma difficult. Devon et al. reported that 14 patients who complicated cancer of anus all had multiple imaging studies, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), CT, and endorectal ultrasound, but none of these studies were diagnostic of carcinoma [14]. The diagnosis of cancer was made preoperatively in 10 of 14 patients, usually after multiple biopsies. In four patients, despite multiple tissue biopsies, the diagnosis was made intraoperatively (n = 2) or postoperatively (n = 2) [14].

The outcome is the same as in sporadic cancer at a corresponding stage; however, the prognosis is often poor due to the advanced stage at diagnosis. There are no formal guidelines for screening and surveillance of cancers associated with CD in the lower rectum and perianal regions. Friedman reported that if the endoscopist is unable to pass the stricture and perform surveillance with a standard pediatric endoscope, a barium enema or CT colonography should be considered to evaluate the proximal colon, with possible referral to an expert center [15].

7.4.1 MRI Examination

For anorectal cancer, pelvic MRI is the best method for examining cancer localization and invasion, as well as its positional relationship with surrounding organs. An anal fistula carcinoma related to mucinous cancer frequently forms mucus retention; thus multilocular cyst-like findings are frequently observed in T2-weighted MRI images. Figure 7.1 shows T2-weighted MRI findings of a mucinous cancer case, with multilocular cysts indicated by an arrow.

Fig. 7.1

T2-weighted images in patient with mucinous carcinoma. Multilocular cysts indicated by an arrow

7.4.2 FDG-PET Examination

Some recent reports indicated the potential of FDG-PET to assess CD activity [16–18]. On the other hand, there is no report of the potential of FGD-PET to assess CD-associated malignant tumors. In our study, we performed FDG-PET with four patients prior to the operation, and the results indicated that two were positive and two were negative. Based on our limited experience, the accuracy rate for FDG-PET is not high, possibly because of the high rate of mucinous cell-type carcinoma in CD-associated cancer. In addition, Whiteford et al. reported that the sensitivity of FDG-PET for detecting mucinous carcinoma was lower than that for nonmucinous cancer [19].

7.4.3 Curettage of the Fistulous Tract

Severe chronic complicated perianal disease in patients who have CD seems to be associated with an increased risk for cancer in the lower rectum and anal canal. Laurent et al. noted that a high degree of suspicion for carcinoma must be considered during a rectal examination under anesthesia with biopsy, curettage, or brushing of the fistulous tract recommended [20]. The case which performed curettage of the fistula under anesthesia is shown in Fig. 7.2. The outflow of mucus is shown from a primary lesion.

Fig. 7.2

Curettage of the fistula under anesthesia. This patient was diagnosed with mucinous adenocarcinoma

7.5 Preoperative Treatment

7.5.1 Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy

No conclusions can be drawn regarding the efficacy of adjuvant chemoradiation in CD patients with fistula-associated anal adenocarcinoma because of the small population analyzed and the retrospective nature of the present study. Mucinous rectal adenocarcinoma has been associated with a lower response to chemoradiation than nonmucinous rectal cancer [21–23]. Sengul et al. compared the outcome after preoperative chemoradiation in 16 patients with mucinous rectal cancer and 55 patients with nonmucinous rectal cancer. Patients with mucinous tumors were found to have significantly more advanced T stages after chemoradiotherapy. Only 18 % of patients with mucinous cancer compared to 74 % of patients with nonmucinous cancer had a shift toward earlier T and N stages [21].

On the other hand, Wolfgang et al. reported that they had good results with combined neoadjuvant chemoradiation; all seven of their patients who received this treatment had a complete response, and they believe that neoadjuvant chemoradiation may play an important role in the treatment of locally advanced disease [24].

7.5.2 Case Presentation

Figure 7.3 shows the CD patients with complicated lower rectal carcinoma. He was 31 years old, and he had 15 years CD history. His preoperative pathological diagnosis was mucinous carcinoma. He was performed preoperative chemoradiotherapy and performed abdominoperineal rectal resection. Details regarding the per-treatment MRI examination, postoperative resected specimen, and pathological examination for that patient are provided in Fig. 7.3. He subsists without local recurrence 6 years after the operation.

Fig. 7.3

CD-associated lower rectal carcinoma. (a) Preoperative MRI examination showing a tumor occupying most of the pelvic cavity. (b) Necrotic tumor specimen resected from the lower rectum. (c) Pathological examination results of a mucinous tumor with inflammatory cells. No malignant cells were found in this specimen

7.6 Surgical Treatment

The objective of surgery for cancer in CD is resection of the cancer for cure or, when indicated, palliation and removal of associated or discontinuous segments of inflammatory disease when necessary. Surgical resection is generally accepted as the basic step in the treatment of these patients. Information on the adjuvant role of chemotherapy or radiotherapy is limited. Advanced rectal carcinomas are usually treated with preoperative pelvic irradiation. In patients with inflammatory bowel disease, however, this treatment produces an increased risk for severe gastrointestinal complications [25].

7.6.1 Small Bowel Cancer

7.6.1.1 Characteristic

There is a strong association between CD and small bowel cancer. The increased relative risk of small bowel cancer has been reported to be between 15.6 and 114.5 in comparison to the general population [26–30]. Cancer of the small intestine occurring in combination with CD is not as common as cancer of the large intestine. In addition, since cancer of the small intestine developing in patients with CD occurs in infected regions, it is very difficult to detect the disease at an early stage. This is because X-ray images of small intestinal cancer are similar to the images of strictures in patients with CD.

Making a definitive diagnosis of combined cancer was not possible before surgery, and the definitive diagnosis is obtained based on an intraoperative or postoperative pathological diagnosis. Palascak et al. reported that small bowel cancer was difficult to diagnose and was made preoperatively in only 1 of 20 patients who had CD as compared with 22 of 40 patients who had sporadic adenocarcinoma [31].

If we encounter such cases, we worry about whether to perform the reoperation or not, because the basic of surgery differs from CD and cancer.

7.6.1.2 Operative Procedure

Segmental resection is the performed surgical therapy for small bowel cancer in segmental CD. In patients with multiple small bowel strictures, concomitant strictureplasties should be performed in addition to the resection of the malignant stricture. Each stricture should be biopsied with frozen section evaluation to rule out the presence of synchronous cancers before a strictureplasty is carried out [32].

7.6.1.3 Case Presentation

A male developed diarrhea and fever at the age of 18 years and was diagnosed with CD in a detailed investigation. He had poor compliance to the prescribed drug therapy and visited the hospital on an irregular schedule. At the age of 34, he was admitted to our hospital for close examination of repeated ileus symptoms that had begun about 4 months prior to treatment. As the ileus symptoms became aggravated, a long tube was inserted. Figure 7.4 shows findings obtained in a series of images of the small bowel, in which a lesion suggestive of internal fistula was noted near the terminal ileum.

Fig. 7.4

Preoperative small intestinal examination

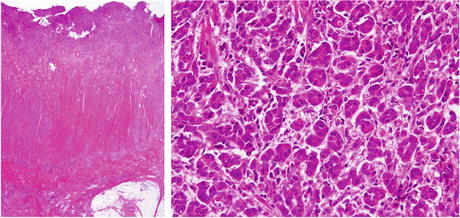

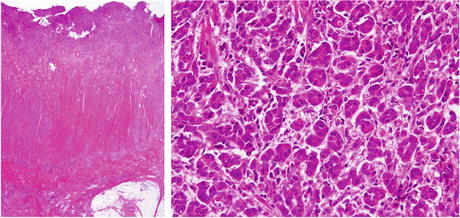

Surgery was performed to remove the segment. During the laparotomy, multiple nodes were found in the peritoneal cavity and subjected to an intraoperative pathologic examination, which led to a diagnosis of peritoneal dissemination of a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. The lesion was surgically removed and an artificial anus was created on the opening side. The resected specimen is shown in Fig. 7.5. Cancer invasion was observed up to the serous surface and distention of the gut on the opening side. We determined that this was a case of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (Fig. 7.6).

Fig. 7.5

Resected specimen in CD patient with small intestinal cancer. A lesion suggestive of internal fistulation was noted near the terminal ileum

Fig. 7.6

Postoperative pathological findings. We determined that this was a case of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma

7.6.2 Colon Cancer

7.6.2.1 Segmental Resection

Segmental resection is the performed surgical therapy for colonic cancer in segmental CD.

7.6.2.2 Subtotal Colectomy

Subtotal colectomy is the procedure of choice in the presence of CD of the colon with malignant degeneration and sparing of the rectum. Following an abdominal colectomy, long-term surveillance with yearly endoscopy and biopsies of the remaining rectal segment is essential.

7.6.2.2.1 Case Presentation

A 30-year-old woman underwent complete resection of the colon and an ileostomy for multiple colonic lesions and a rectovaginal fistula. Thereafter, there was no close examination of the rectum as no aggravation of the rectovaginal fistula was noted. During a uterus cancer screening examination at the age of 40, an adenocarcinoma was found. She then came to our hospital for careful investigation of the remaining rectum, in which a carcinoma was found in a rectovaginal fistula on the rectal side. She underwent amputation of the remaining rectum. The resected specimen is shown in Fig. 7.7.

Fig. 7.7

Carcinoma in a rectovaginal fistula in a patient with CD

7.6.2.3 Total Proctocolectomy (TPC)

This procedure is generally performed for colonic cancer patients with pancolitis or with segmental colon and rectal disease or with colon and severe perianal disease.

7.6.2.4 The Surgical Treatment of CD-Associated Dysplasia

It remains unresolved whether total proctocolectomy is required for colorectal cancer or dysplasia in CD as it is in UC or whether segmental resection might be adequate [33]. In CD, once dysplasia is identified, segmental resection is a more feasible option, especially if there has been a consistent lack of inflammation elsewhere in the intestinal tract [33]. In the patients with multifocal colonic dysplasia or rectal dysplasia, the need for an aggressive approach, namely, TPC, is easily justified. Moreover, in CD patients with severe perianal disease or incontinence, TPC with end ileostomy offers treatment of the anal disability not provided by lesser resections such as segmental colectomy or IRA. Most surgeons favor TPC when cancer or dysplasia is discovered in the colon, but this usually results in a permanent ileostomy. Both total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis (IRA) and segmental colectomy in CD patients with comorbidities are possible alternatives but require careful preoperative patient counseling regarding cancer risk and compulsive postoperative surveillance of any remaining colorectum.

There has been a case of colonic high-grade dysplasia (HGD) reported in a patient with CD that recurred as metastatic cancer despite subtotal colectomy followed by annual colonoscopy surveillance with biopsy [34]. Therefore, to make a definitive recommendation about the management of colonic dysplasia in CD, a large study would be required.

7.6.3 Cancer in Enteroenteric or Enterocutaneous Fistula

7.6.3.1 Characteristic

Cancer of the internal or external fistula occurring in combination with CD is not as common as cancer of the large intestine. In addition, it is very difficult to detect the disease at an early stage. This is because X-ray images of fistula cancer are similar to the images of usual CD patients.

7.6.3.2 Case Presentation (Internal Fistula)

An ileal bladder fistula was found at around the age of 40 years old in a male patient, and surgical treatment was recommended. However, it was left untreated, as no symptomatic aggravation occurred. After hematuria continued for 1 month, he visited the urology department at the age of 54. A cystoscopic examination found a tumor, which was diagnosed as mucinous cancer based on biopsy findings. Total pelvic exenteration was performed. A perioperative radiogram image and the excised specimen are shown in Fig. 7.8. The patient died of cancer at 8 months after the operation.