12 Surgical Therapy of Early Breast Cancer

Introduction

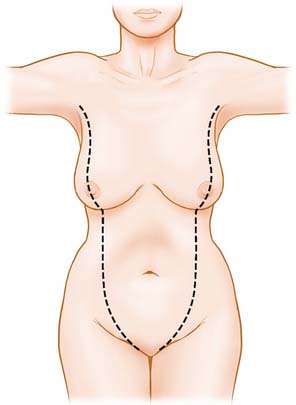

Breast tissue is broadly distributed along the milk line from the axilla to the groin, and breast cancer can arise at any of these ectopic locations (Fig. 12-1). Ectopic breast cancer, however, is rare, and surgical treatment is local excision. Most breast cancers occur in the breast proper, and surgical treatment of these tumors is the focus of this chapter.

Figure 12-1 Distribution of breast tissue along milk lines.

(From Marshall MB, Moynihan JJ, Frost A, Evans SRT: Ectopic breast cancer: case report and literature review. Surg Oncol 3:295–304, 1994, Figure 1.)

Breast cancer treatment requires both locoregional control in the breast and axilla as well as prevention and control of distant metastatic disease. Distant control of metastatic disease is obtained through chemotherapy, hormone therapy, or biologic therapy. Locoregional control is attained through surgery and radiation therapy to the breast, chest wall, and axilla. Surgical procedures for early breast cancer therapy are mastectomy or lumpectomy. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary lymph node dissection are used to provide staging information as well as local control of metastatic disease in the axilla; these are discussed further in Chapter 15.

History

In this century, surgery remains the central aspect of breast cancer treatment, as it has for millennia. In the mid-1860s, Edwin Smith acquired an ancient manuscript thought to have originated in Egypt around 1600 bc and believed to be a copy of a text 1000 years older.1 It includes the first recorded description of breast cancer and, although the author concluded that breast cancer was not treatable, this didn’t stop others from trying. Around 2000 bc, physicians on the Indian subcontinent were treating breast cancer with surgery, cautery, and arsenic compounds.2 By 460 bc, Hippocrates was describing breast tumors as a buildup of “black bile” (melanchole). Around 200 bc, Galen, the surgeon to Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, noted that the only way to cure breast cancer is complete surgical excision in early-stage disease. Another Roman surgeon, Aulus Cornelius Celsus, knew the problem of local recurrence in 100 bc “after excision, even when a scar has formed, none the less the disease has returned.”3 Whether “complete excision” could be done sufficiently with lumpectomy or required mastectomy was debated in the surgical literature until the mid-1900s.

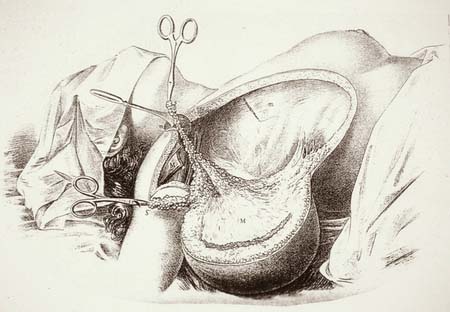

In 1894, Halsted4 published his experience with a procedure subsequently labeled the Halsted radical mastectomy for the local control of breast cancer (Fig. 12-2). He developed this procedure based on the work of other contemporary surgeons of his day. He used anesthesia, antisepsis, and strict hemostasis to remove the skin, breast, pectoralis major and minor muscles, and the axillary contents, including infraclavicular and supraclavicular nodes en bloc. One of the most important but often overlooked aspects of this achievement was that none of Halsted’s patients died from sepsis. Before this report, up to 50% of the women undergoing mastectomy died from infection within the first 2 weeks after surgery. Information about aseptic technique had just recently been incorporated in surgical procedures, and this, combined with Halsted’s early practice of leaving the chest wound open to heal by secondary intention, increased short-term survival to 100%. He subsequently used skin grafts to cover the large open wound.

Figure 12-2 Halsted mastectomy.

(From Halsted W: The Results of Operations for the Cure of Cancer of the Breast Performed at The Johns Hopkins Hospital from June 1889 to January 1894. The Johns Hopkins Hospital Reports. The Johns Hopkins Press, 1894, p 33)

Dr. Halsted’s patients were left with disfiguring and large wounds with minimal impact on long-term, cancer-specific survival: breast cancer left untreated has a 2.7-year average survival, whereas Halsted’s patients had a 3-year average survival. In addition, his patients experienced significant morbidity. Differences in sociologic norms of the day are best expressed in Halsted’s own words:

After all, disability, ever so great, is a matter of very little importance as compared with the life of the patient. Furthermore, these patients are old. Their average age is nearly 55 years. They are no longer very active members of society. We should, perhaps, sacrifice many lives if we were to consider the disability which might result from removing a little more tissue from here and there.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree