Surgical prophylaxis remains the most effective means to prevent breast cancer. Strategies for risk reduction include bilateral prophylactic mastectomy (BPM), contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM), and prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (PBSO). BPM is performed for risk reduction in women who have not been diagnosed with cancer. In contrast, CPM is performed in patients with a diagnosis of unilateral breast cancer for risk reduction of contralateral breast cancer.1 Current guidelines for prophylactic mastectomy (PM) include patients with BRCA1/2 mutations, other predisposing gene mutations, strong family history with no demonstrable mutation, and prior mantle radiation for Hodgkin’s lymphoma, all of which confer a significantly higher risk for breast cancer than for the general population.2,3 Discussion of risk-reduction procedures is complex and should be individualized to ensure the best oncologic and psychosocial outcomes for each patient.

The first report of PM was described by Bartlett in 1917.4 By the 1970s, it was estimated that approximately 600 to 700 prophylactic mastectomies were being performed annually in the United States.5,6 However, a number of retrospective studies have indicated that the incidence of both CPM and BPM has increased significantly in recent years.7–12

Subcutaneous mastectomy was first described by Rice and Strickler in 1951.13 Typically, a rim of normal breast tissue was left underneath the nipple-areolar complex (NAC) to give the remaining chest wall a more natural appearance before the development of modern breast reconstructive techniques.14–16 However, it became apparent with long-term follow-up that subcutaneous mastectomy did not adequately prevent high-risk patients from developing breast cancer.17,18 With the discovery of BRCA1/2 gene mutations, simple, or total, mastectomy (defined as removal of the NAC, all grossly evident breast tissue, and preservation of the axillary contents) was felt to provide greater risk reduction.15,19,20

Due to significant improvements in breast reconstructive options, skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) is currently the most common type of mastectomy performed for risk reduction.16 First described by Toth and Lappert in 1991, this procedure involves removal of all breast tissue and the NAC while maintaining the skin envelope of the breast.21 The main advantage of this procedure is an improved cosmetic outcome as the native skin envelope allows for better appearance, position, and shape of both prosthetic and autologous-tissue reconstructions.21–23 When it was initially introduced, a major concern was the amount of residual breast tissue remaining on the longer skin flaps, inframammary fold, and axillary tail.24 Barton et al25 evaluated this by comparing 27 cases of mastectomy with minimal skin excision and variable treatment of the NAC in high-risk patients to 28 cases of modified radical mastectomy (MRM). They biopsied six sites along the chest wall, in the axilla, and on the skin flaps and found residual breast tissue in 22% of the high-risk mastectomy cases versus 21% of the MRM cases.25 These data indicate that SSM is equivalent to simple mastectomy in removing all of the grossly visible breast tissue.25

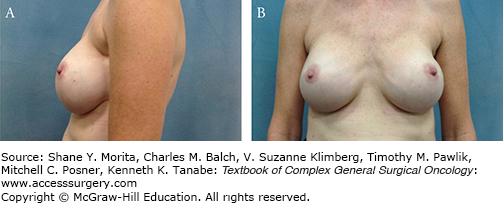

Women reported losing the NAC to be distressing and noted increased satisfaction with breast reconstruction when the NAC was reconstructed in addition to the breast mound.26 However, factors such as lack of projection, color match, and shape of the reconstructed NAC correlated with patient dissatisfaction.27 Patients’ desire to maintain their native nipple fueled the interest in total skin-sparing mastectomy (TSSM).22,28 TSSM removes all of the breast tissue including the ductal tissue located in the NAC and preserves the entire skin of the breast (Fig. 69-1).29,30

Removal of all of the breast tissue behind the NAC followed by careful pathologic evaluation of the cored out nipple tissue is an important component of TSSM. Terminal ductal lobular units, where ductal carcinoma arises, are present in 9% to 24% of nipples and because 9% of primary breast cancers arise in the nipple, tissue underlying the NAC must be sectioned coronally to adequately examine for the presence of malignancy22,28,31–34. Patient selection criteria for TSSM include no history of previous chest irradiation and no excessively large or ptotic breasts.29,35,36 To determine oncologic safety, Peled et al37 studied 26 patients with BRCA1/2 mutations who underwent BPM with TSSM and reported that no breast cancer developed with a 4-year follow-up. Two other studies with a substantial proportion (18% to 25%) of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers undergoing BPM with TSSM in their cohorts reported no breast cancer occurrences with mean/median follow-up of 10 to 43 months.29,38 Based on a 95% risk reduction from PM, the additional risk of breast cancer is projected to be 1% to 2% with NAC preservation in women who are BRCA1/2 mutation carriers and undergoing BPM.28 However, to date, no long-term follow-up data exist in actual BRCA1/2 mutation carriers undergoing TSSM.

The risk of identifying an occult breast cancer in the PM specimen is 3% to 5%, although greater than 50% are noninvasive cancers.39–42 When an occult cancer is detected in a PM specimen, a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is difficult to perform without the intact breast. In this situation, a complete axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is the recommended procedure; therefore, the rationale to perform SLNB in conjunction with PM is to avoid an unnecessary ALND. Laronga et al39 conducted a single-institution retrospective review of 449 patients who underwent CPM and SLNB and found a 2% incidence of positive sentinel node(s). Others report a similar incidence of 0% to 3.5% of CPM cases with a positive SLNB.42–47 The complications of SLNB are better understood now and include axillary and arm paresthesias, pain, limitations of upper arm and shoulder range of motion and most significantly, lymphedema, which can occur in 3% to 7% of cases.41 Therefore, based on the risk of occult invasive cancer, the risk of a positive SLNB is low and routine SLNB should not be performed with PM. For certain patients, MRI can be useful in determining who should undergo an SLNB.41,47–50 However, the cost of MRI remains high and thus, routine preoperative use of MRI is not recommended.47

Multiple retrospective and prospective cohort and case-control studies have investigated the risk reduction of breast cancer with BPM in mutation carriers and high-risk patients. BPM, especially in combination with PBSO, offers the greatest risk reduction for patients that are at high risk for breast cancer.17,51 Rebbeck et al prospectively studied 483 women with BRCA1/2 mutations who underwent BPM and compared them to women who underwent surveillance; the authors determined a 90% risk reduction at a mean follow-up of 6.4 years. Of note, the two women in this study who developed breast cancer after BPM had subcutaneous mastectomies.17 More recently, Domchek et al52 reported that among BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, no breast cancers developed in 247 women who underwent BPM compared to 98 breast cancers in 1372 women who did not have BPM with a median follow-up of 3.65 years. Other studies have found similarly that risk reduction approaches approximately 90% with BPM.18,53 Evans et al54 reported prospective data collected from 10 European centers on BRCA mutation carriers and high-risk women; of the 314 women who underwent BPM, no breast cancers developed during a mean follow-up time of 7.5 years. These studies have not shown statistically significant differences in cancer incidence after BPM associated with the type of mastectomy performed.17,18Table 69-1 details the studies of breast cancer occurrence in high-risk patients after BPM.

Studies of Bilateral Prophylactic Mastectomy (BPM) and Breast Cancer Occurrence Following the Procedurea

| Author | Year | Patient Type | Total Patients | No. of Pts with BPM | Follow-up (Mean or Median) | No. of Breast Cancers Following BPM | Location of Breast Cancers (No. of Cases) | Type of Mastectomy | Risk Reduction of Breast Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartmann et al18 | 1999 | 639 | 639 | 14 yrs | |||||

| High risk | 214 | 214 | 3 | Chest wall (1), bone met (1), nipple (1) | Subcutaneous | 90–94.3% | |||

| Mod risk | 425 | 425 | 4 | Chest wall | Subcutaneous | 89.5% (p < 0.001) | |||

| Meijers-Heijboer et al53 | 2001 | BRCA 1/2 | 139 | 76 | 2.9 yrs | 0 | HR 0 (95% CI 0–0.36) | ||

| Contant et al111 | 2002 | BRCA 1/2, HB(O)C | 79 | 79 | 2.5 yrs | 0 | |||

| Rebbeck et al17 | 2004 | BRCA 1/2 | 483 | 105 | 6.4 yrs | 2 | Axillary LN met, chest wall | Subcutaneous | 90–95% |

| Geiger et al112 | 2005 | Mod risk | 276 | 276 | 10.3 yrs | 1 | HR 0.0005 (95% CI 0.001–0.044) | ||

| Heemskerk-Gerritsen et al113 | 2007 | High risk | 177 | 177 | 4.5 yrs | ||||

| BRCA 1/2 | 145 | 145 | 1 | Met disease | SSM | ||||

| HB(O)C | 32 | 32 | 0 | ||||||

| Evans et al54 | 2009 | High risk, BRCA 1/2 | 314 | 314 | 7.5 yrs | 0 | 90% | ||

| Domchek et al52 | 2010 | BRCA 1/2 | 2482 | 247 | 3.65 yrs | 0 | |||

| Kaas et al114 | 2010 | BRCA 1/2 | 147 | 147 | 3.7–6.1 yrs | 0 | |||

| Skytte et al115 | 2011 | BRCA 1/2 | 307 | 96 | |||||

| BRCA 1 | 201 | 67 | 3 | Chest wall (2), axilla (1) | Simple | ||||

| BRCA 2 | 106 | 29 | 0 | ||||||

| Arver et al116 | 2011 | High risk | 223 | 223 | 6.6 yrs | 0 | |||

| BRCA 1/2 | 129 |

In terms of improved survival with BPM, one retrospective study reported an 81% to 94% reduction in breast cancer-specific mortality depending on patient classification into high- and moderate-risk groups.18 Another study reported no deaths in 76 women with BRCA1/2 mutations who had BPM compared to one death from breast cancer in 63 patients who underwent surveillance.53 The 2010 Cochrane review proposes for patients at increased risk of breast cancer that risk reduction after BPM may translate into improved breast cancer-specific survival and overall survival, especially when performed at an earlier age.55 Other authors have modeled survival outcomes in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers after BPM and found that if performed at age 30, BPM can improve life expectancy by 2.9 to 5.3 years.56–58

More recently, overall PM rates have increased dramatically, fueled by CPM rates that have risen by 150%.9 A number of retrospective studies have demonstrated that CPM reduces the incidence of breast cancer by 94% to 97%.55,59,60 BRCA1/2 mutation carriers have approximately a 90% risk reduction of contralateral breast cancer after CPM.61Table 69-2 details the studies of contralateral breast cancer occurrence in high-risk patients after CPM. However, much of the data showing a survival benefit of CPM are inconsistent and limited by selection bias.55,60–63 Large database reviews from the National Cancer Database (NCDB) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) have failed to demonstrate a survival benefit to CPM. In 14,994 patients from the NCDB database with stage I–III breast cancer who underwent CPM, the 5-year survival benefit was only 2% after adjusting for confounding variables. The authors concluded that the benefit of CPM was minimal even in women younger than 70 years with stage I or II index tumors.64 Carson et al65 examined the NCCN database and determined there was no overall survival benefit with CPM for patients with DCIS or stage I–III index cancers over a median follow-up of 4.5 years compared to unilateral mastectomy. Bedrosian and colleagues66 found that the only group to derive a benefit from CPM were young women with early-stage ER-negative breast cancer, resulting in a 5% improvement in breast cancer-specific survival. In addition, some argue that a survival benefit after CPM requires longer follow-up since the mortality in the first decade after diagnosis is due to the primary cancer.67 Therefore, factors such as age and overall health status of the patient as well as the prognosis of the primary cancer are considerations when deciding which patients are appropriate for CPM.

Studies of Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy (CPM) and Contralateral Breast Cancer Occurrence Following the Procedurea

| Author | Year | Patient Type | Total Patients | No. of Pts with CPM | Follow-up (Mean or Median) | No. of Contralateral Breast Cancers Following CPM | Location of Contralateral Breast Cancer | Type of Mastectomy | Risk Reduction of Contralateral Breast Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peralta et al62 | 2000 | 246 | 64 | 6.8 yrs | 0 | ||||

| McDonnell et al59 | 2001 | Positive family history | 745 | 745 | 10 yrs | 8 | Chest wall (4), axillary LN (4) | Subcutaneous (4), simple (4) | 94.4–96% (p < 0.05) |

| Goldflam et al117 | 2004 | Unilateral, early-stage breast cancer | 239 | 239 | 7.8 yrs | 1 | SSM | >90% | |

| Positive family history | 140 | ||||||||

| Metcalfe et al118 | 2004 | BRCA 1/2 | 491 | 146 | 9.2 yrs | 1 | 97% | ||

| Herrinton et al60 | 2005 | All comers | 1389 | 1072 | 5.7 yrs | 5 | 97% | ||

| van Sprundel et al61 | 2005 | BRCA 1/2 | 148 | 79 | 3.5 yrs | 1 | Chest wall | 91% | |

| Heemskerk-Gerritsen et al113 | 2007 | High risk | 181 (91 BRCA 1/2, 90 HB(O)C) | 4.5 yrs | 0 | ||||

| Evans et al54 | 2009 | High risk, BCRA 1/2 | 236 | 236 | 7.5 yrs | 0 | 90% | ||

| Kaas et al114 | 2010 | BRCA 1/2 | 107 | 107 | 4.2–5.8 yrs | 1 | Axilla |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree