Fig. 10.1

Risk-adapted strategies to manage the inguinal region among patients with penile cancer and no palpable inguinal adenopathy. For reliable patients in the low-risk group, careful observation is recommended. Among patients in the intermediate- to high-risk group, an inguinal staging procedure is often recommended such as dynamic sentinel node biopsy or superficial inguinal dissection

Expectant Management of the Inguinal Region

Compliant patients with primary tumors exhibiting carcinoma in situ (Tis), verrucous carcinoma (Ta), and stage T1 grade 1 tumors exhibit less than a 10 % incidence of positive lymph nodes overall and are optimal candidates for watchful waiting strategies [13, 25]. Recommendations for the management of T1 grade 2 tumors vary based on quoted rates of subsequent metastases. The former EAU guideline, while classifying such cases in the intermediate-risk group, recommended observation for T1 grade 2 tumors that lacked vascular invasion and exhibited a superficial growth pattern (i.e., absence of any other adverse features) [12]. This guideline was recently modified to recommend an inguinal staging procedure for this group of patients [13]. Given the low rate of metastases overall in a recent study of 9 % [27], we agree with the Société Internationale d’Urologie/International Consultation on Urological Diseases recommendation that these patients may also be considered for observation. All other cases should be considered for surgical staging. It is imperative for the patient and the physician to adhere to such follow-up agreements and be willing to intervene immediately if initial inguinal parameters change. Leijte et al. documented that only a third of patients with initially negative nodes but subsequently had an inguinal recurrence survived 5 years [28]. Modified inguinal procedures offer less invasive alternatives to traditional lymphadenectomy for patients with no palpable inguinal adenopathy but who are at significant risk for inguinal microscopic metastases.

Surgical Inguinal Staging Procedures for the Clinically Negative (cN0) Inguinal Field

Dynamic Sentinel Node Biopsy

DSNB offers the potential for precise localization of the sentinel node with the lowest morbidity of any surgical staging technique to our knowledge [28]. The goal of DSNB is to define where in the inguinal lymph node field the sentinel lymph node resides using a combination of visual (vital blue dyes) or gamma emission (handheld gamma probe) techniques at the time of surgery. Several studies evaluating the results of DSNB as a staging tool in penile cancer are now available. Kroon et al. described the use of a combination of preoperative lymphoscintigraphy and intraoperative intradermally injected blue dye in 123 patients with penile cancer [29] (Fig. 10.2). They identified a sentinel node in 98 % of patients, for a sensitivity rate of 82 % and a false-negative rate of 18 % (6 patients). Four of the 6 patients subsequently died of disease progression. Spiess et al. also reported a false-negative rate of 25 % among 31 patients undergoing DSNB [30]. In that study the sentinel node was found in the expected superomedial quadrant in 85 % of cases. However, it was detected in a more lateral location in 9 % of cases and in both locations in 6 % of cases. Kroon et al. subsequently instituted several changes, including (1) routine serial sectioning of the involved lymph nodes along with cytokeratin immunohistochemistry, (2) routine exploration of groins with low or no signal subsequent to preoperative or intraoperative studies, and (3) inguinal ultrasonography with FNA to detect subtle architectural changes (nonpalpable) in positive lymph nodes that could result in the redistribution of lymphatic flow [31].

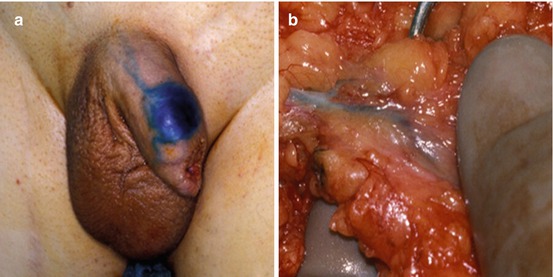

Fig. 10.2

A 67-year-old patient with stage T2N0M0 squamous carcinoma of the penis who previously underwent a partial penectomy and had a unilateral positive preoperative lymphoscintigraphy on the left side shown in anterior-posterior view

In a multicenter update that included patients assessed with the modified DSNB protocol from 2 high-volume centers, Netherlands Cancer Institute and St. George’s Hospital in London, the false-negative rate was 7 % (6 of 323 patients) [32]. Three of the 6 patients with recurrence (50 %) either died or had distant metastases. Thus, DSNB, when performed at high-volume centers using a standardized protocol, has an acceptable sensitivity, but deaths from penile cancer of patients with initial negative nodes still occurred [32]. This result limits the applicability of this strategy to larger centers with experienced surgeons and nuclear medicine specialists. Figure 10.3a demonstrates injection of isosulfan blue dye intradermally with blue dye noted in the penile shaft lymphatics. Subsequent to percutaneous identification of radioactivity over the specific inguinal area, an inguinal incision is created and the involved node(s) determined by either radioactive counts or blue staining are removed (Fig. 10.3b).

Fig. 10.3

Dynamic sentinel node biopsy (DSNB) for penile cancer. (a) Demonstration of the injection of isosulfan blue dye during DSNB at the site of the surgical scar from a previous partial penectomy and (b) subsequent demonstration of staining of lymphatic channels and sentinel node with DSNB

Superficial Complete Inguinal Dissection

A superficial inguinal complete dissection has been proposed as a staging tool for the patient without palpable inguinal lymphadenopathy. Superficial node dissection involves removal of those nodes superficial to the fascia lata. Subsequent to DSNB and superficial dissection, Spiess et al. showed lymphatic drainage in upper lymph node quadrants lateral and medial to the femoral vessels (see Fig. 10.1) [30]. Thus, a medial quadrant dissection or biopsy could produce false-negative findings. Leijte et al. reported similar findings when performing single-photon emission CT before DSNB [23]. A complete ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy (removal of those nodes deep to the fascia lata contained within the femoral triangle as well as the pelvic nodes) is then performed if the superficial nodes are positive at surgery on frozen section analysis.

The rationale for superficial dissection is that two series have shown no positive nodes deep to the fascia lata unless superficial nodes were also positive [33, 34]. Furthermore, Spiess et al. reported that of those patients with negative lymph nodes undergoing DSNB with completion of superficial dissection, none with a negative superficial dissection had recurrence at more than 3-year follow-up [30]. Thus, a superficial inguinal dissection should adequately identify microscopic metastases in patients with clinically normal inguinal examination findings without the need for a pelvic dissection if the inguinal nodes are negative. The disadvantage is the higher overall complication rate (12–35 %) compared to that of DSNB (5–7 %) [3, 29]. A superficial dissection provides more information than biopsy of a single node or group of nodes, and the possibility of not identifying the sentinel node is limited by removal of all potential first echelon nodes. The dissection is readily performed by any surgeon experienced in inguinal surgery without the need for specialized equipment. Figure 10.4 demonstrates some of the steps involved in performing a superficial inguinal dissection.

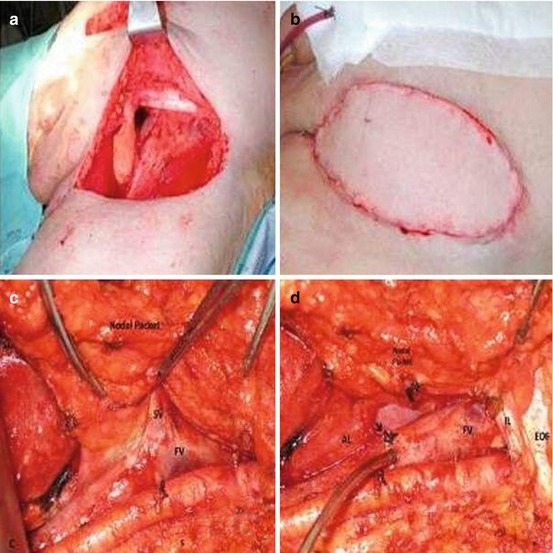

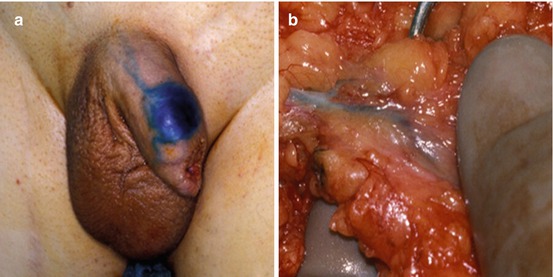

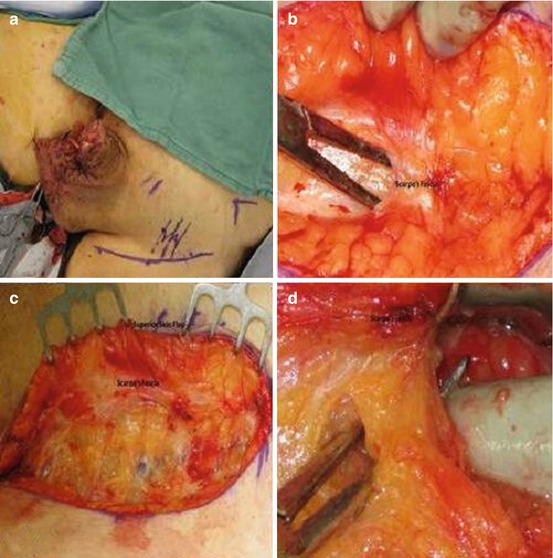

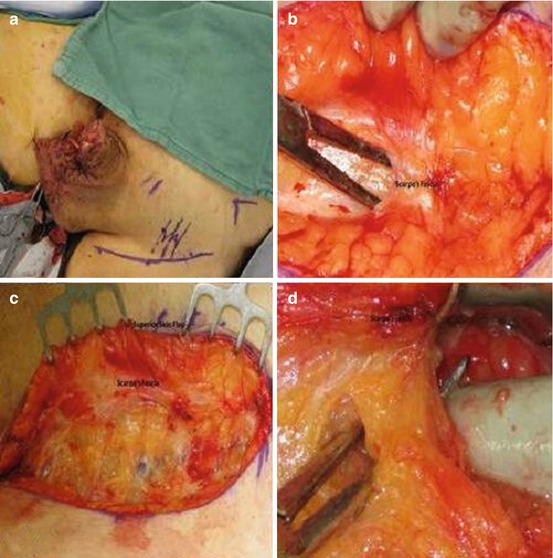

Fig. 10.4

Superficial inguinal lymph node dissection. (a) Left inguinal incision two fingerbreadths lateral to and inferior to pubic tubercle. Midpoint located over the femoral vessels. (b, c) Incision carried down to Scarpa’s fascia and skin flaps raised just below the fascia. (d) With flap elevated nodes dissected from beneath the fascia to free the superior skin flap. (e) Left superomedial border of dissection identified by spermatic cord. (f) Inferior skin flap raised by dissecting Scarpa’s fascia away from underlying nodes. (g) Self-retaining retractor placed and nodal tissue divided over the saphenous (SV) and femoral veins (FV) dividing specimens into medial and lateral packets. (h) Medial packet mobilized off the adductor longus (AL) fascia and the medial surface of saphenous and femoral veins. (i) Lateral packet nodes mobilized off the sartorius muscle fascia(s). (j) Completed superficial dissection. Sartorius (right) and adductor longus muscular fascia (left) are visualized as well as the femoral canal (FC) medial to the femoral vein (FV). Note that the femoral artery (FA) is not skeletonized by removing superficial nodes

Laparoscopic/Robotic Inguinal Lymphadenectomy

Both the laparoscopic and robotic approaches to the inguinal region offer the potential of removing all of the inguinal lymph nodes at risk for disease while minimizing complications. The technical details of the contemporary procedure and early results have been described (see Fig. 10.5) [35–37]. To date the results of laparoscopic and robotic inguinal lymphadenectomy have been comparable to those of open inguinal lymph dissection with comparable node counts achieved in both. A single case of inguinal recurrence reported at 12- to 33-month follow-up, and minor complications in about 20 % of patients have been reported [3, 38]. However, in one study using a laparoscopic approach with over 600 days of follow-up, Master et al. noted minor complications in 27 % of patients with major complications noted in 14.6 % [39]. These were mainly infectious in nature and were managed with intravenous antibiotics or incision and drainage. Of note among 41 dissections, there was only a single case of skin edge necrosis. Matin et al. using a robotic-assisted approach noted in a phase one pilot study that dissection was equivalent to an open approach in 18/19 (94.7 %) cases when verified by a second surgeon using an open incision to inspect the same groin [37]. Thus, these minimally invasive approaches, although promising, will require further validation with larger patient numbers and longer follow-up to better determine efficacy and complication rates.

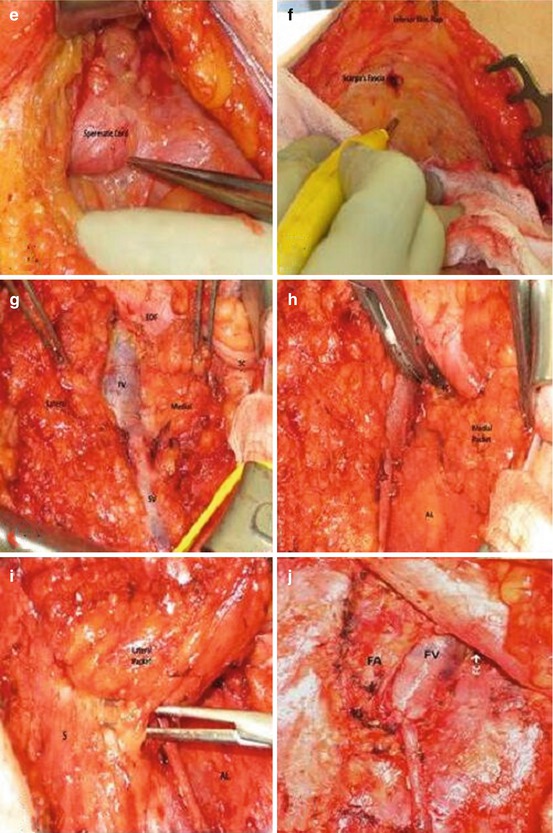

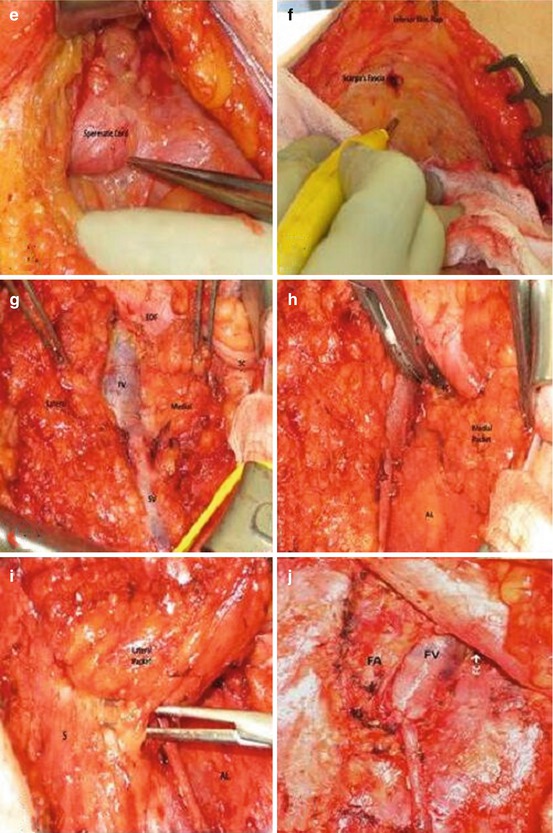

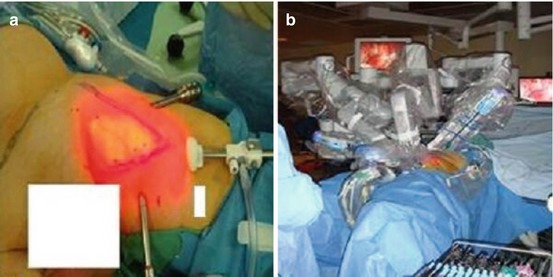

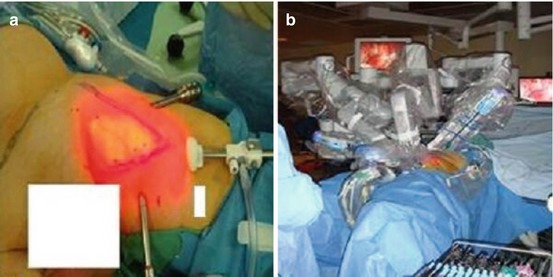

Fig. 10.5

Robotic-assisted inguinal lymphadenectomy (RAIL) for penile cancer. (a) Boundaries of the femoral triangle are marked based upon cutaneous landmarks. Camera port (c) located 3 cm below the apex of femoral with robotic ports (R) placed one handsbreadth diagonally proximal to the camera port. A 12-mm assistant port (not shown) is placed between the cameral port and one of the robotic ports. (b) Docking alignment for the RAIL procedure. The robotic surgical cart is docked on the opposite side of the table directly in line with the inguinal field to be explored

Surgical Management of Advanced Regional Metastasis from Penile Cancer

Mobile Unilateral or Bilateral Inguinal Adenopathy

Penile cancer patients exhibiting inguinal metastases that are highly curable with surgery alone include those with one to two unilateral inguinal metastases with no evidence of extranodal extension (ENE) into the perinodal adipose tissue. In a recent series reported by Graafland et al., the 5-year cancer-specific survival among patients with three or more positive inguinal nodes, ENE, bilateral positive inguinal nodes, or proven pelvic metastases were 33, 42, 51, and 22 %, respectively, whereas those with two or less involved inguinal nodes, no ENE, unilateral metastases, and no pelvic metastases exhibited 74, 68, 80, and 72 %, respectively, 5-year cancer-specific survival [40]. Of note in their series, adjuvant radiation therapy was often used among patients with two or more positive inguinal nodes and ENE [40].

Given the adverse outcomes associated with poor-risk pathological findings, post inguinal lymphadenectomy predicting those patients destined to have such findings based upon preoperative clinical staging could be beneficial given the potential benefits of utilizing neoadjuvant chemotherapy to reduce the metastatic load prior to surgery [41, 42].Recently Graafland et al. described computerized tomography (CT) scan findings that were highly correlated with adverse pathological findings at surgery [43]. Among 30 patients with palpable adenopathy, CT scans were evaluated independently by two radiologists who were blinded to subsequent surgical pathology findings. CT parameters evaluated related to lymph node findings included short-axis diameter, central necrosis, indistinct margins, irregular nodal border, and infiltration of adjacent soft tissue. The investigators reported that among this cohort the CT scan findings of central necrosis or an irregular nodal border exhibited a sensitivity and specificity of 95 and 82 %, respectively, for predicting the presence of three or more positive inguinal nodes, ENE, or positive pelvic nodes. The latter is especially relevant as CT itself using size criteria alone for pelvic metastasis identified only 2 of 10 positive pelvic fields [43].

Preoperative fine needle aspiration (FNA) can also be utilized among patients with palpable inguinal adenopathy to define the presence of bilateral metastases. In addition among patients with abnormal pelvic CT scans, pelvic metastases can be confirmed by CT-directed biopsy. Saisorn et al. reported a 93 % sensitivity and 91 % specificity in 16 patients with palpable adenopathy (mean size 1.47 cm) undergoing FNA before lymphadenectomy [44]. Thus, among patients suspected to harbor potentially incurable inguinal metastases with surgery alone, preoperative imaging along with needle biopsy may assist in the selection of patients for neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Bulky Adenopathy, Fixed Nodes, and Inguinal Tumor Recurrence

Treatment options for the patient with an unresectable groin mass consist of palliative surgery alone, up-front combination chemotherapy with surgical consolidation, radiotherapy, or chemoradiotherapy [45]. Ornellas et al. treated 39 patients with advanced penile cancer with palliative lymphadenectomy with reconstructive techniques to close soft tissues defects [46]. They reported that the procedures were associated with little morbidity or mortality and that there were improvements in short-term quality of life. However, it was noteworthy that only 4 of 39 patients (10 %) survived 12 months. One patient did survive, however, for 5 years [46].

Modern chemotherapy regimens have shown an overall response rate of 31–50 % [42, 47], with some responders showing a pathological complete response (i.e., no viable disease remaining at the time of surgical consolidation). To our knowledge there has only been one prospective neoadjuvant chemotherapy trial in penile cancer. The combination chemotherapy agents used were cisplatin, paclitaxel and ifosfamide. Of 30 patients with clinical N2-3 disease, 73 % underwent post-chemotherapy surgery, and 30 % were alive and free of recurrence at a median follow-up of 34 months. Two patients died of unrelated causes, such that the long-term progression-free survival rate approached 40 % [42]. Leijte et al. from Netherlands Cancer Institute have reviewed their experience with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with initially “unresectable” penile cancer [41]. The series included 20 patients treated with five different regimens including (1) single-agent bleomycin; (2) bleomycin, vincristine, and methotrexate; (3) cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil; (4) bleomycin, cisplatin, and methotrexate; and (5) cisplatin and irinotecan. The objective responses were evaluable in 19 (one patient died due to bleomycin toxicity after 2 weeks) with 12 responses (63 %, 2 complete, 10 partial) [41]. Surgical procedures included treatment of the primary tumor as well as inguinal and pelvic dissections. Additional soft tissue resection including bone was sometimes required. Vascularized tissue flaps were used for inguinal reconstruction. Among 12 responders only 9 went to surgery, as two died of bleomycin-related complications while the third was deemed unfit for surgery [41]. Eight of nine responding patients taken to surgery (two were pT0) were free of disease with a median follow-up of 20.4 months. This is in contrast to three nonresponders who went to surgery for palliative intent. All three died within 4–8 months due to locoregional recurrence [41]. The implications from the above studies suggest that response to chemotherapy together with an aggressive surgical procedure provides the optimal scenario for significant palliation or potentially cure. Up-front surgical resection may provide palliation of pain or prevent erosion of tumor into the femoral vessels, but survival for more than a year is rare.

Technique for Post-Chemotherapy Ilioinguinal Lymphadenectomy

After completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and hematologic recovery, patients should be assessed for clinical evidence of response to chemotherapy based on clinical and radiologic parameters. Patients that are medically fit post-chemotherapy and have had an objective response to chemotherapy are optimal candidates for resection. We have previously described surgical techniques utilized in prior publications [3, 48, 49]. Of importance, surgical incisions were planned to allow for resection of grossly palpable or visible residual disease with negative surgical margins and to leave the normal surrounding tissue. Thus, a wide ellipse of normal skin was often included in the resected specimen (see Fig. 10.6a). The resected tissue also included the underlying lymph nodes between the lateral borders of the adductor longus and sartorius muscles, with complete removal of the muscular fascia, skeletonization of the femoral vessels, and en bloc resection of the saphenous vein (Fig. 10.6c–f). Ancillary procedures occasionally used to achieve negative margins, such as resection of the femoral vessels or abdominal wall, have previously been described [48, 49].