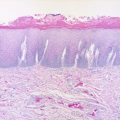

Fig. 5.1

Crusted thin early SCC with sun damage to the entire vermilion. Suitable case for vermilionectomy

Laser vermilionectomy has been used for premalignant lesions of the lower lip [3] (Fig. 5.2), and other studies have examined its use for early invasive carcinoma. In one report of 46 patients with T1 SCC of the lip with a minimal follow-up of 5 years, disease-free survival (DFS) was 82.6 % following the use of Nd:YAG laser ablation [4]. Although the authors concluded that these results support the use of the Nd:YAG laser for stage 1 cancers of the lip, the literature generally reports a survival of >90 % in stage 1 disease. It should also be noted that 6 patients in the above cohort of 46 required repeat laser ablation.

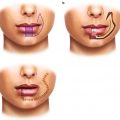

Fig. 5.2

(a) Dysplastic leukoplakia of the lower lip marked for carbon dioxide laser vermilionectomy from wet line to skin-vermilion border. (b) After three passes at 2 W continuous beam

Squamous cell carcinoma of the lips behaves more like skin cancer than mucosal oral cavity epithelial malignancy, and Mohs surgery has been used for these cancers. In a large series of 1,119 patients with stage I (983 %) and stage II (1.7 %) SCC of the lower lip, local recurrence was only 1.5 % [5]. Another paper analyzing Mohs surgery found a 91 %, 5-year cure rate in 45 patients with early stage SCC of the lower lip [6].

In larger lesions and lesions thicker than 2–3 mm, full-thickness excision is utilized (Fig. 5.3). There are few good trials to assess the margins necessary for excision of SCC of the lip. Older studies advocate 8–10 mm as for mucosal SCC of the oral cavity [7]. However, it is difficult to reconcile the removal of such a margin with the excellent results for microscopic margins reported for Mohs. De Visscher et al. [8] reported a more conservative approach in a clinical trial of 72 patients with SCC of the lower lip, where 3 mm margins controlled by intraoperative frozen sections were used. They found 89.9 % of margins were initially clinically free and a false-positive result of 1.4 % for frozen section. Local recurrence was 2.8 % with a minimum 2-year follow-up. They advocated a 3 mm margin with frozen sections and a 6 mm margin if frozen sections were not used [8]. Brotland and Zitelli [9] in a prospective study of cutaneous SCC not specifically located to the lip advocated 4 mm margins. However, in high-risk lesions, i.e., 2 cm or more in size, histologic grade 2 or higher, invasion of the subcutaneous tissues, and location in high-risk areas, these authors prefer 6 mm margins[9]. In the absence of prospective trials, it appears that early stage I SCC of the lip may be managed with margins 3–5 mm. However, when the size of the primary tumor is >2 cm, there is an increased rate of local recurrence [10–12] and margins of at least 10 mm are required. Resection can be undertaken with a V- or shield-shaped full-thickness excision especially in small tumors. In larger thicker tumors extending below the skin-vermilion border, these tapering excisions may compromise margins and a vertical incision such as a W or rhomboid is preferred (Fig. 5.4). Where the whole vermilion has premalignant changes, a vermilionectomy can be incorporated with the excision.

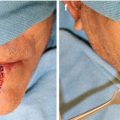

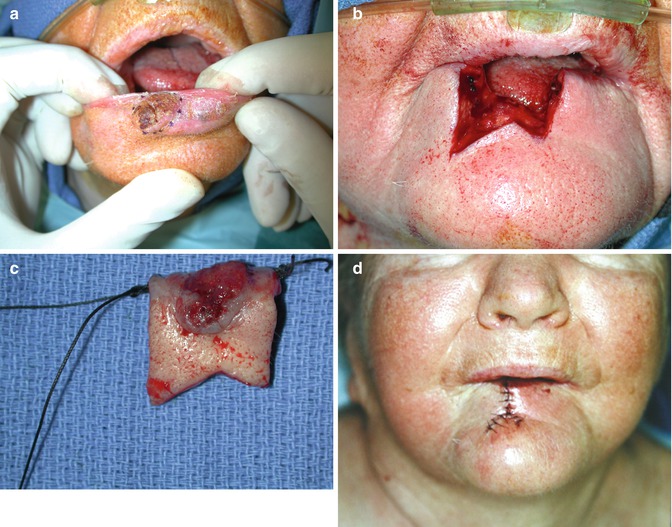

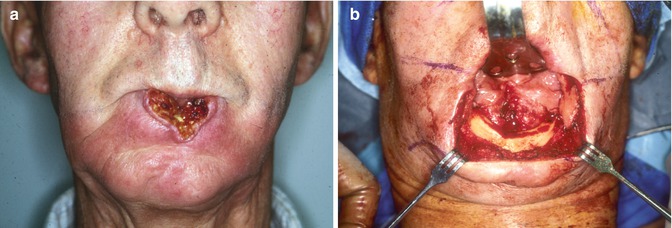

Fig. 5.3

(a) T1 SCC left lower lip marked out with shield-shaped excision 5 mm margins. Figure (b) shows excision in full-thickness repair will be in three layers, mucosa, muscle, and skin

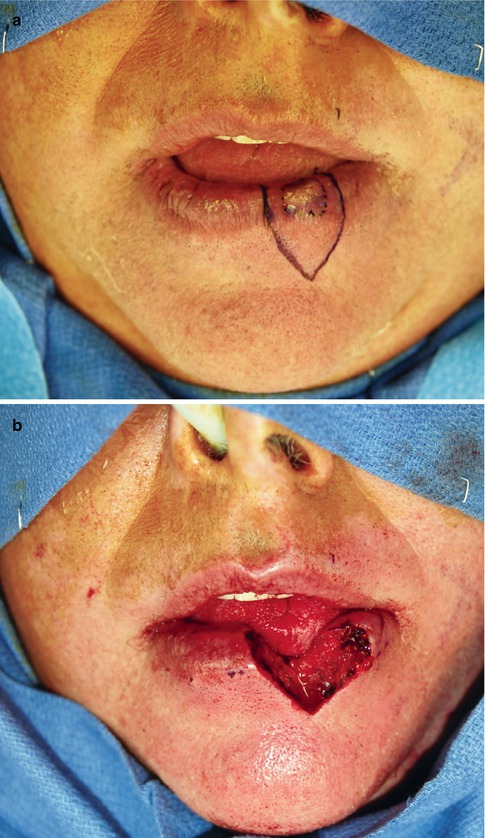

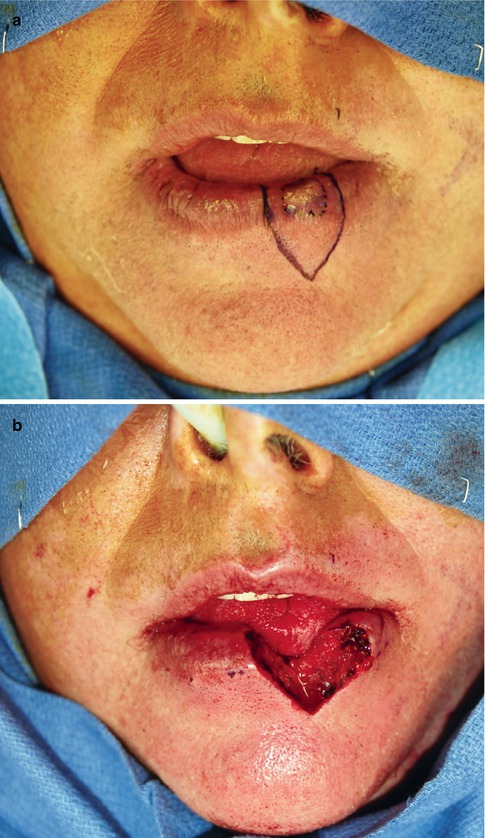

Fig. 5.4

(a) 1.5 cm T1 SCC right lower lip. (b) SCC excised with W pattern placing inferior limbs in the submental crease. (c) Specimen marked with sutures. Margins were 8 mm and intraoperative frozen sections performed. (d) Postoperative after closure in three layers

As the tumor increases in size, adjacent structures to the lip may become invaded by direct extension and both the mandible and inferior alveolar nerve may require management. In cancers of the lower lip, the mandible will be managed as for intraoral SCC. If the tumor is close to the bone but not fixed to it and the periosteum can be stripped without evidence of perforation or invasion, then the mandible can be left intact. When the tumor is stuck to the periosteum or is eroding/invading the cortical bone, only then a marginal resection with preservation of mandibular continuity is indicated (Fig. 5.5). In more advanced cases where invasion through the cortical bone into the medullary bone is present, then a segmental resection of the involved bone is the safest oncologic procedure.

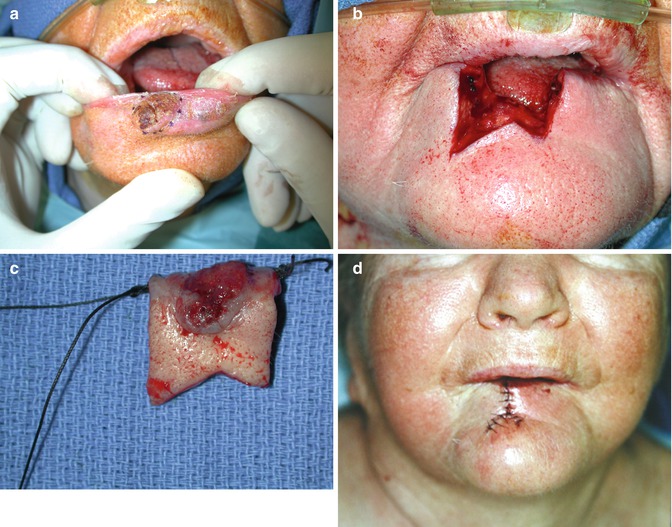

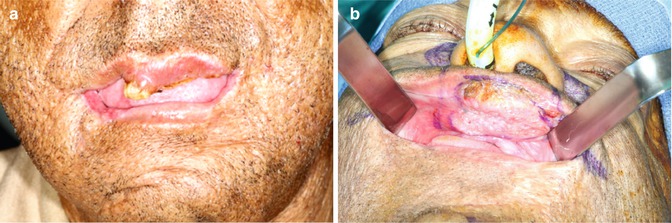

Fig. 5.5

(a) Recurrent SCC lower lip post primary therapy with RT. Tumor involves the buccal cortex of the mandibular symphysis. (b) Intraoperative view, the upper lip is retracted with a sweetheart retractor. The lower lip has been excised 1.5 cm margins and a marginal mandibulectomy performed

The mental nerve may be involved by tumor invasion and the SCC can spread in theory along the nerve to the foramen ovale with intracranial involvement [13]. Patients have symptoms of sensory disturbance of the lip, and the panoramic radiograph may show widening of the mental foramen or mandibular canal [14]. If sensory changes are diagnosed preoperatively, resection of the nerve with frozen section control should be planned. Magnetic resonance imaging may be the most accurate way of defining the extent of perineural involvement, but it is reported that usually only 10–15 mm of nerve is involved in lip cancer [15]. However, if the nerve is involved within the mandible, the surgeon may need to remove the entire nerve bearing segment of the mandible.

Adjuvant radiation therapy (RT) is usually given for T3–4 tumors, and if the final margins are positive, either re-resection or chemo/radiation is recommended. Perineural invasion is also believed to be an indication for postoperative RT.

5.3 Management of the Neck

The central third of the lower lip drains to the submental nodes, although occasionally it can drain to the submandibular nodes on either side. The lateral third of the lip drains to the submandibular nodes although occasionally can go to the submental. The nodes at level I are therefore almost always the first echelon nodes for the lower lip, and from level I, the jugulodigastric node and other level II nodes are involved. Drainage from the upper lip is, however, more complex. It is most common for the upper lip to drain to the submandibular nodes on the ipsilateral side. Rarely the upper lip may drain first to the submental nodes. Occasionally though the upper lip may drain initially to the parotid nodes either preauricular or parotid tail nodes. As this pattern of drainage is less predictable than the lower lip, when dealing with a large upper lip SCC which is clinically N0 but at high risk for occult metastasis, imaging may be helpful, especially PET scanning (Fig. 5.6).

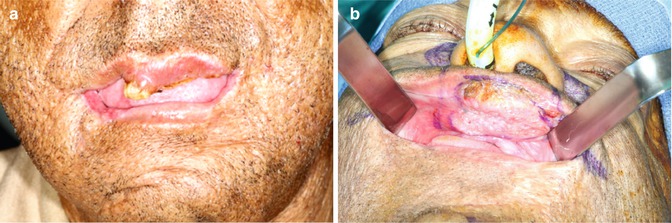

Fig. 5.6

(a) Seventy-year-old African American male with previous excision of half the lower lip for SCC now presents with keratinaceous lesion of the upper lip. (b) Retraction of the upper lip reveals a 4 cm SCC. Clinical and PET/CT revealed no nodes

Unlike intraoral SCC the majority of lip cancers present early as the lesion is apparent when it is small T1 in size. Therefore, in most large series, the percentage of involved lymph nodes is not high. In Zitsch et al.’s series of 1,000 patients, only 64 patients had cervical metastases at presentation (6.4 %), while a further 34 (3.4 %) went on to develop regional disease. Six patients had both initial and delayed cervical nodes [16]. In Frierson and Cooper’s series of 187 patients, 14 patients presented initially with cervical disease (7.4 %) and 16 patients developed delayed neck involvement (8.6 %) [17]. In another retrospective series of 617 patients, 130 patients (21 %) had clinically palpable nodes thought to be malignant. This higher figure may be explained by the fact that in this cohort of patients, only 53.3 % presented with T1 tumors [18].

In patients presenting with positive nodes on initial clinical examination, imaging, and fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB), a neck dissection is indicated. In cases with N1 neck or involvement at only level I data from other oral cavity sites would suggest that a selective neck dissection (SND) levels I–IV or a modified radical neck dissection (MRND) should be performed. If final pathology shows N2 disease, then adjuvant RT is recommended, and if extracapsular spread (ECS) is diagnosed, then chemo/radiation is the standard of care. However, Gooris et al. suggest that a supraomohyoid neck dissection SOHND may be sufficient in lower lip SCC with metastasis confined to level I. In a series of 44 cases, 24 pN1 and 20 pN2 with 28 patients (64 %) having ECS, regional recurrence occurred in only four patients (9 %). Their protocol was for SOHND with no adjuvant therapy in pN1 disease with no ECS and postoperative RT for either pN2 disease or ECS. All four patients who failed regionally recurred in the dissected field, and all had a combination of pN2 + ECS [19]. This approach of SOHND for positive level I nodes due to lower lip cancer had been suggested as possibly sufficient treatment in an earlier study by Kowalski et al. [20].

When N2 disease is diagnosed, a MRND is utilized with postoperative RT. In extensive disease with multiple large or fixed nodes, a true radical neck may be necessary followed by chemo/radiation. In tumors of the central third of the lip with a node in one neck, a bilateral neck dissection is undertaken with an elective SND on the N0 neck.

In upper lip cancer with a positive node in the parotid, a parotidectomy and a SOHND including level 2b is carried out, and in cases that have nodes in both parotid and the neck, parotidectomy is combined with MRND. If postoperative histopathologic examination of the neck dissection specimen reveals only one node with intranodal disease, no adjuvant therapy is indicated. In N2 disease radiation therapy is given, and for extracapsular spread, chemo/radiation is the recommended adjuvant therapy.

Although only a small percentage of patients will develop delayed metastases, it is important to try and predict which patients are at high risk for occult disease and may benefit from elective SND, and this remains somewhat controversial. Many different factors predictive for delayed onset of cervical nodes have been studied including size of the tumor, site (upper lip, lower lip, or commissure), histologic grade, tumor thickness, and patient age. In Zitsch et al.’s study, high histologic grade was the single most significant factor with primary tumor size also significant [16]. Byers et al. found that only 2 % of all their lip cancers showed perineural invasion yet 80 % had cervical metastasis as opposed to 10 % in the patients with no neural involvement [21]. Similar results were reported by Frierson and Cooper [17]. De Visscher et al. showed tumor thickness, an infiltrative pattern of invasion, and perineural invasion to be significant factors in nodal disease [22]. The 2004 study by Vartanian et al. revealed that T3–4 tumors and involvement of the commissure were significantly related to occult neck nodes [18]. In the most recent studies, size of the primary tumor has been implicated as the major predictor of neck disease [10, 11] (Fig. 5.7).

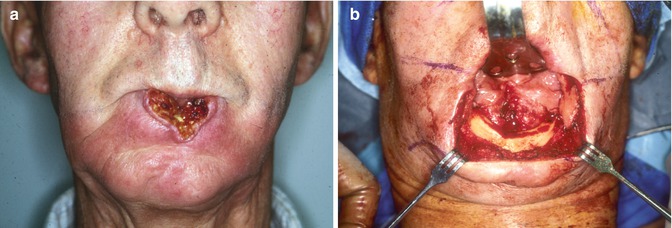

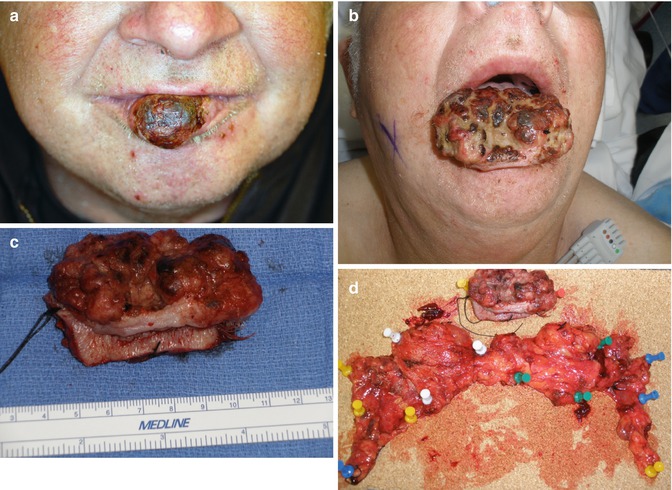

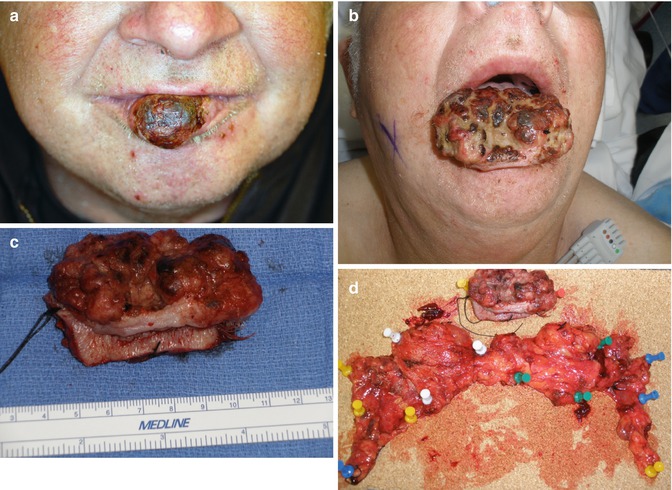

Fig. 5.7

(a) T2 SCC on central third of lower lip. (b) Surgery delayed 4 months by patient, now presents with T4 primary cancer growing rapidly. No neck nodes clinically and radiologically but will receive an elective bilateral SOHND. (c) Intraoperative close-up view of total lip resection specimen. (d) Complete specimen, bilateral SOHND neck dissections, and lip pinned out to orient for the pathologist. Final pathology negative but patient received RT postoperatively for T4 tumor size

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree